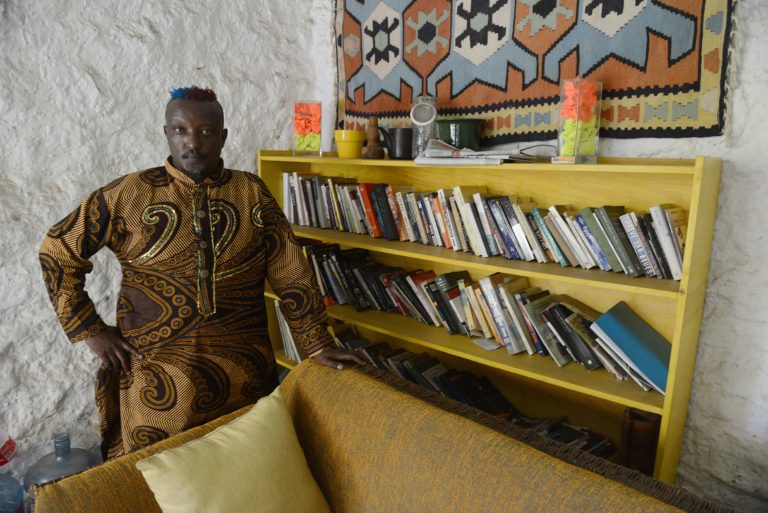

Binyavanga Wainaina

The Ethics of Aid: One Kenyan's Perspective

We explore the complex ethics of global aid with a young writer from Kenya, Binyavanga Wainaina. He is among a rising generation of African voices who bring a cautionary perspective to the morality and efficacy behind many Western initiatives to abolish poverty and speed development in Africa.

Image by Simon Maina/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Binyavanga Wainaina is the founding editor of Kwani?literary journal and the director of Bard College's Chinua Achebe Center for African Languages and Literature.

Transcript

August 27, 2009

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Ethics of Aid: One Kenyan’s Perspective.” We explore a challenging view of the morality and efficacy of Western approaches to Africa’s problems.

MR. BINYAVANGA WAINAINA: A lot of people arrive in Africa to assume that it’s a blank empty space and their goodwill and desire and guilt will fix it. And that to me is not any different from the first people who arrived and colonized us. This power, this power to help, is just about as dangerous as hard power, because very often it arrives with a kind of zeal that is assuming ‘I will do it. I will solve it for you. I will fix it for you,’ and it rides roughshod over your own best efforts.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Scarcely a week goes by without the launch of yet another new high-profile initiative to abolish poverty and speed development in Africa. Yet there is little uncontested overarching evidence that hundreds of billions of dollars of aid over the past 50 years have made a significant long-term difference to the health and wealth of people on the African continent.

Faced with this fact, philanthropists, governments, and celebrities pursue more intensive aid and new innovative approaches, but the primary concern of my guest this hour, Binyavanga Wainaina, and a rising tide of other young African intellectuals and economists is the debilitating psychological effect prolonged multidirectional aid has on the very people it is aiming to help. It sends this underlying message Binyavanga Wainaina wrote satirically in a British paper: “We can save you from yourselves. We can save ourselves from our terrible selves. We want to empower you. No, your mother cannot do this. Your government cannot do this. Time cannot do this. Evolution, it seems, cannot do this. No one can empower you except us.”

This hour, we’ll explore the complex ethics of global aid through Binyavanga Wainaina’s eyes and his writing. He and I spoke in 2008.

From American Public Media this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas.

Today, we begin an occasional series on the ethics of aid with one Kenyan’s perspective.

MR. WAINAINA: A lot of people arrive in Africa to assume that it’s a blank empty space and their goodwill and desire and guilt will fix it. And that to me is not any different from the first people who arrived and colonized us. This power, this power to help, is just about as dangerous as hard power, because very often it arrives with a kind of zeal that is assuming ‘I will do it. I will solve it for you. I will fix it for you,’ and it rides roughshod over your own best efforts.

MS. TIPPETT: Binyavanga Wainaina was born in 1971 in Nakuru in the Rift Valley province of Kenya. He studied commerce in South Africa and began his life as a freelance writer there. He founded the Nairobi-based literary journal Kwani? and publishes widely in leading newspapers and magazines also in the U.S. and Great Britain. He writes, often satirically, of what he sees as a paradoxical relationship between the ideals and motivations of Western organizations and the needs and motivating spirit of those they want to help.

Here is a reading from an essay he published in the British literary magazine Granta, which has been widely read, reprinted, and discussed across Africa. It is an example of his satirical style, a mock tip sheet for Western journalists titled “How to Write About Africa.”

READER: “Broad brushstrokes throughout are good. Avoid having the African characters laugh or struggle to educate their kids or just make do in mundane circumstances. Have them illuminate something about Europe or America in Africa. Describe in detail dead bodies. Or better, naked dead bodies. And especially, rotting naked dead bodies. Remember, any work you submit in which people look filthy and miserable will be referred to as ‘the real Africa,’ and you want that on your dust jacket. Do not feel queasy about this. You are trying to help them to get aid from the West.

“Animals, on the other hand, must be treated as well-rounded complex characters. They speak (or grunt while tossing their manes proudly) and have names, ambitions, and desires. They also have family values. Elephants are caring and are good feminists or dignified patriarchs. So are gorillas. Any short Africans who live in the jungle or desert may be portrayed with good humor (unless they are in conflict with an elephant or gorilla, in which case they are pure evil).”

MS. TIPPETT: Of all that Binyavanga Wainaina criticizes, he says the problem begins with seeing Africa as an undifferentiated reality, not a continent comprised of over 50 countries, many of which only came into being as distinct independent nations in the 1950s and 1960s. He is a vocal critic of the failings of his own leaders. In the very same spirit, he is a hopeful and passionate defender of Kenya’s young democracy and of the necessity of that country’s best and brightest to contribute to the long-term creation of a robust, successful nation.

Binyavanga Wainaina was born in the wake of Kenyan independence in 1963. He grew up through the tumultuous 24-year presidency of Daniel arap Moi, which was marked by human rights abuses, economic upheaval, and corruption. Yet Kenyan life, African life, Binyavanga Wainaina insists, is not and has never been a monolithic story of poverty, need, and despair, and too often this is the story donor aid assumes and cultivates even in Africans themselves.

MR. WAINAINA: For a large part of my childhood, I guess the donor world didn’t really register in any significant way. We felt that there were many problems in Kenya, but we felt too that, you know, much had moved. My grandparents were born dirt poor. They hardly had any schooling. My grandmother had 12 children. She’d managed to get — on a two-acre piece of land — 12 of her kids through university. Kenya is the country that between 1963 and 1969 multiplied the production of cash crops that even the British colonial government could not do.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: So all those villages where people talk about the poorest of the poor were places that delivered people who are leaders right now. Obama’s father.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right, right.

MR. WAINAINA: Out of small schools. Those were places my parents were born in.

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote an article, “How to Write About Africa,” which is about how there is this kind overriding picture, and I think, you know, the starving orphan in Sudan is pretty quintessential.

MR. WAINAINA: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: And that becomes the image of Africa in Western imaginations, and it becomes this galvanizing image on the basis of that image that all kinds of great aid ideas are launched. But that starving orphan in Sudan is real, right?

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Does exist.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, and so I’m asking you to engage in a conversation with the imagination of my listeners. So how would you ask people to start to discern where there really is a humanitarian crisis, where any and all help from anywhere should come immediately, and then how to start to draw boundaries to think about, as you say, a reform of the very notion of aid?

MR. WAINAINA: Yes. Well, your guess is as good as mine, because I guess your listeners are stuck in the same problem that I am, because I was reading Andrew Sullivan’s blog, a place I love to go, and somewhere I assume he heard something terrible was happening in Congo. So he put this photo of this burnt child, which is like, ‘oh my god, isn’t that terrible?’ and then he moved on. Now, you know, that precisely is the problem. That you need this kind of weird shock appeal so someone is like, ‘I’ve got to do something.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And then if you Google enough, there will be someone with a child just like that looking at you and telling you, ‘Click here and send a dollar.’ So you pay some guilt money. But then after a while, you’ve paid some guilt money, and next year you’ll need something more horrific to notice, because you get more and more numb the more and more horror you witness. So you have this campaign that’s going, you know. I don’t even know how much our GDP has fallen because of just the ubiquitous photographs of us looking like that. I don’t know for every dollar given in that way how many dollars of somebody wanted to invest in a business in Nairobi have gone away.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, I see.

MR. WAINAINA: And so the ethics of those pictures to me, I mean, really, I can’t tell you how much they are upsetting, because someone just keeps telling you the urgency of the situation. People in Darfur are dying. I’m like if you have to dehumanize people to that degree, for them to die, if it is that the Western audience is so inattentive to a possible genocide that that is what you have to do, don’t do anything. Leave us alone.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. WAINAINA: Yes. Let us just solve our own problem. That should not be a way that human beings deal with each other.

MS. TIPPETT: You note in that article, I mean, it’s very striking and disturbing, that the descriptions and narrative about elephants in Africa, for example, about wildlife, present them in a much more three-dimensional way …

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … than human beings in refugee camps or starving orphans. I mean, it’s …

MR. WAINAINA: And of course what’s really ironical about it is that as you sit here watching it on CNN, in Nairobi you’re watching yourself on CNN too.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. WAINAINA: So we were sitting when the blood broke in Kenya, seeing the man with the panga. There was one shot that they just kept showing, was a man with a panga hacking somebody to death just not two miles from where I live.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And to me that just became the image of the year. And it was kind of horrible, because what was going on in Kenya was horrible, that is no question, but, I mean, we’ve had 15 years of just working so hard to make things happen.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. WAINAINA: And we can just be reduced to that moment.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you wrote something I found very interesting in The New York Times about that post-election violence in Kenya, in your country this year.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: You just put it in historical perspective, you know?

MR. WAINAINA: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: You said we are 45 years old this year. And you haven’t here in this conversation with me, you didn’t in that article, deny that horrible things were happening, that it was bad, but you said nations are built on crises like this.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: “If there is such a thing as Kenya, which is a fairly new concept, reality, it should be gathering energy right now. The moment is now to make a solid thing called Kenya.” I’m often aware, in conversations I have about all kinds of issues in the world in other parts of the world, it’s very hard for Americans in particular to bring any kind of historical perspective …

MR. WAINAINA: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: … including how dicey it was when this democracy was 45 years old.

MR. WAINAINA: Sure. I mean, there are so few people on the continent who’ve not thought that our hopes were always improbable. I mean, you know, whatever fight that people were having to have a viable nation, et cetera, there’s not a thing that’s happened to us in the last century that’s positive that hasn’t been about defying what the odds are.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: Defying the odds of the overwhelming power somebody has over you, defying the odds of being able to manage something where, you know, some colonial leaves and takes everything away and being able to do it. And I can’t tell you that Kenya will work or it won’t work, but right now my sense is that the relationship between here and there is more cynical. Our best intellects are working in American colleges right now.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And they’re working in American colleges because they cannot be viably employed in Kenya.

MS. TIPPETT: Now you’ve also written about the 1990s in Kenya …

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … as really formative for you also in thinking forward, kind of imagining different reality. And you’ve talked about how Kenya was a subsidized economy for 30 years. And there’s a really striking sentence — that I think for Americans is striking. You wrote something about during that period, you did not need to be creative. And then you do describe in the ’90s, and I want you to fill this in, but a country unraveling, right, that’s the picture, Western donors pulling out. And then you said Nairobi became one giant heaving market and you said, “We were all becoming hustlers.”

MR. WAINAINA: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Is that experience something that gives you some idea about the kind of reality-based contours of how this might be different?

MR. WAINAINA: Yeah. I mean, since the ’90s what had become a stagnant thing called Kenya was standing up, lifting itself, and starting to move. And with that move what happened was an enormous amount of opportunities were created and an enormous amount of threats. So, for example, the fact that the economy is doing well is very much delicately tied with the violence that happened in January, because suddenly there’s a stake. There’s no apathy anymore. Everyone wants a bit of the cake and the cake doesn’t satisfy everybody.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: So things become very intense because there’s hope again. But hope and its opposite side are two very closely related things. So in a way for my generation, the ’90s were the years of sleep. Those who could not get out of the country dispersed to all manner of places. They built skills. You know, Kenya sends more students to America than any other country — 5,000 a year, I believe. So one of the things that kind of was horrible was this generation who are skilled, who are educated by the state, who moved all those skills to come here and to go elsewhere, who missed home in wartime and find a way to come back. Those who remained home had to become hustlers. You had to find a business; you had to do stuff, et cetera. But one of the things about it is during those sleeping moments people get very creative.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: So I suspect that what has happened is that you have just this very muscular group of people. The kids who went to college after I left Kenya in the early ’90s worked really hard. They didn’t have college grants. They had to work part time. Some of them are selling fruit on the streets while carrying a full-time job. So, I mean, when opportunity presented itself five years ago, you could see the growth happening really quickly, because people were really tough and kind of ready for opportunity.

MS. TIPPETT: Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media, today exploring an African perspective on the complex ethics of some of the vision and strategies behind Western aid and development.

Ms. Tippett: Binyavanga Wainaina believes that young democracies such as that of Kenya are undercut by the clout of foreign aid projects. There is an established link between foreign aid that feeds the corruption of indigenous leaders, corruption of which Binyavanga Wainaina is a vocal critic. But he also describes more subtle distortions created by well-meaning Western donors and organizations. As they pick up essential projects and services, he says, a capacity for offering those services becomes underdeveloped in the host country’s own public infrastructure and nonprofit sector, and global projects are ultimately accountable not to the people they’re serving, but to faraway foreign bureaucracies. They might offer themselves to little or no local scrutiny, questions, or feedback. Binyavanga Wainaina points, for example, to one of the most highly publicized present initiatives, the United Nations’ model Millennium Villages that have been set up in 12 sub-Saharan African countries, including Kenya. They’ve been created in line with the American economist Jeffrey Sachs’ vision of fast-tracking development and abolishing hunger and poverty.

MS. TIPPETT: How do you respond to the images that are very visible in American culture and in global culture now of very powerful and sometimes, you know, really exciting people like Angelina Jolie or Bill Gates or Bono, right …

MR. WAINAINA: Yes. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … who are out to save Africa? And those are different; Bono and Angelina Jolie and Bill Gates are different.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, let’s take Bill Gates who is a very smart guy and has lots of money and is looking specifically at people dying and taking medicine and taking cures. So is that a good thing for you?

MR. WAINAINA: I guess so. I mean, to me the idea that somebody’s going to invest money in researching things like malaria, which are woefully underfunded and that kind of thing, is a wonderful and noble quest. And too, the idea too that the application of good knowledge to make a better world is something I believe in and I support. So if that is happening, I’m really happy. The point is, just because they’re doing it does not exempt them from the same amount of scrutiny I would expect to give my government.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: I’m not here to call somebody the savior of my this when I do not know who you account to and why. So, for example, with the Jeffrey Sachs thing — there was a very good piece in Harper’s Bazaar — you know, the village inside there, I have tons of questions. You know, I have a thousand questions. And I know international media go, they see, they report, and they say it’s wonderful. I don’t know what that thing is.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s happening in your country, right?

MR. WAINAINA: That’s happening in my country.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. WAINAINA: And for some reason has global implications. So the question is not is it good or is it bad; the question is why isn’t it presenting itself for the scrutiny? If it is so good, why is it not saying, ‘We have come to your country, right, and we are open for you to come and see what we are doing and we want your best minds to come tell us what they think is wrong with it.’

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. WAINAINA: I know that certain in the Ministry of Agriculture et cetera are like, ‘Well, what they are doing we did in the ’70s and it didn’t work.’

MS. TIPPETT: Now, I’m sure you’re aware that there is a new generation, comes often under the rubric of social entrepreneurialism: younger activists, often combining business and kind of NGO-type work, who consider this old development model to be broken, the top down. And I think you’ve talked about how there are a few useful development models for genuinely self-starting people. And I think part of the approach of these new entrepreneurs is — I spoke with one of them just a few months ago, Jonathan Greenblatt — is that they don’t come up with big ideas and then test them out or pose them; they look for organic grassroots, self-starting and self-help that’s already happening and then they try to support that.

MR. WAINAINA: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Is that good? Is that a good development? Or is it in danger of some of the same kinds of problems?

MR. WAINAINA: I guess so. Again, as I said earlier on, if you walk around the landscape of Nairobi and see the things that people are doing, there’s just so many incredible things. It’s not the idea that aid is bad and the people who are doing it are bad. They are social entrepreneurs or cultural entrepreneurs. I work for an institution called Kwani, which has received donor money. So my idea here is not to get on the high horse of like point finger.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: It’s just that I need to make a lot of noise and other Africans need to make a lot of noise so that you have a lot more transparency …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … and a lot more clarity. I want to don’t go and find people inside my country doing things that I don’t know and I don’t know why. So in the sense of social entrepreneurship, I believe that’s fine. I can tell you that to my mind all the things that have significantly mattered in the growth of my country have had to do with very concrete things.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: When the government decided to spend 30 percent of the budget of education from the ’60s to the ’70s, they created a class of educated people. I can say that I think a large majority of people who were removed from poverty through the ’50s and the ’60s and ’70s was because of the access to decent primary school education funded by our government — with donor help quite often, by the way …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … and a clear kind of roadmap and stepladder for how somebody could leave a small rural area and end up with a decent job somewhere. And all those things have somehow broken up, and charity has often intervened somewhere and we don’t know. And I could say that in the last 10 or 15 years, the single thing that’s changed the lives of millions of Kenyans has been the rearrangement of banking capital to service the small Kenyan. And banks like Equity Bank, which are micro-lending banks, scaling up the idea that somebody who earns a thousand shillings a month is bankable and someone to invest in and be able to create a model for that person to acquire credit in a reasonable way and grow, that has mattered more than 10 of the donor or a thousand of the donor things, because it believes in the idea that the person on the ground has an idea and that idea can be serviced. And whenever it has happened in the last hundred years, people have created an infrastructure that assumes that the person whose been given that infrastructure is someone who given so will grow, that they have their own ideas, Kenya’s moved forward. And whenever they have assumed that you’re not, Kenya’s moved backward.

MS. TIPPETT: Another Kenyan I’ve interviewed is Wangari Maathi.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, her story is so striking. I mean, at this point you say here is this Nobel Peace Prize winner who’s planted 30 million trees and counting, but it started with such a simple observation. And it was a link that had been broken between trees growing and water and food and work and quality of life. Now it’s a great big huge idea that you can call a movement, but it started so close to the ground. And I also think maybe we don’t tell ourselves those stories about how close things start to the ground that really do work after 30 years.

MR. WAINAINA: Certainly. And how genuinely invested people are in living a better life. You know, good ideas catch on and there’s ample evidence to show this.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Binyavanga Wainaina’s writings, much like this program, challenge preconceived notions about Africa, global development, and donor aid. Read his provocative and influential essays “Oxfamming the Whole Black World,” “How to Write About Africa,” and others on our Web site, speakingoffaith.org.

This program is the first in what we’re planning as an occasional series exploring the ethics of global aid and development from various angles. My producers and I have been discussing this for quite some time as we’ve looked for the right voices and fresh perspective on this complex topic. We’ve written about that process and its challenges on our blog, SOF Observed, and we’ll be posting more of our ideas as we pursue future shows on this issue. Find links to the blog and this week’s program through our home page, podcast, and e-mail newsletter. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: After a short break, Binyavanga Wainaina’s thoughts on how citizens of the West can nuance their perspective and turn good intentions into true partnership with Africans.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Ethics of Aid: One Kenyan’s Perspective.”

My guest, Binyavanga Wainaina, is a Kenyan writer and journalist. He’s currently teaching at Williams College in Massachusetts. He publishes widely across the African continent as well as in major U.S. and British media. Africa’s problems, he knows, are the result of multiple layers of history and responsibility. These include Western colonialism but also the corruption of indigenous leaders since most African nations gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s. But Binyavanga Wainaina has been describing to me the deep concern he also holds about unintentional debilitating effects of prolonged multidirectional Western aid and development projects, especially in a fledgling democracy like Kenya. He writes, often satirically, of what he sees as a paradoxical relationship between the ideals and motivations of Western organizations and the needs and motivating spirit of those they want to aid.

MS. TIPPETT: Something I didn’t ask you at the beginning. Was there a religious or spiritual background in your family, in your upbringing?

MR. WAINAINA: Yes. And I’m not particularly religious myself. My mother was, very. My father’s family were very kind of Presbyterian.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WAINAINA: My grandmother was a big, big, big, big, fierce churchwoman. She went preaching around the whole of East Africa.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And my granddad on my mother’s side — let’s just put it like this: The Catholic cathedral of the district is on his land, so …

MS. TIPPETT: OK. All right.

MR. WAINAINA: And I guess, like many families who managed to make it, you come from that early generation of people who were Mission-educated. And what is amazing is just how much good work is often done by the churches …

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. WAINAINA: … you know, to this day. Some of the most interesting projects I’ve seen, the Catholic Church networks, et cetera, really do exceptional work, the Muslims as well, in a certain way, because you have a very long relationship with people and you understand their value.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, that’s interesting, right.

MR. WAINAINA: And they do the things themselves. So when we had a drought in ’84, the Catholic Church decided to do these water projects. They brought technology. You know, the valley water has a lot of fluoride, and the project for the Catholic Church did provide water, get the community participating in paying money, you know, the relationship of the priest with his parishioners, quite often doing projects even in places where people are not necessarily Catholics. It’s just very much on the ground. It’s very sensible. It’s very cost effective and it’s very natural and it’s part of our lives. It’s not the sort of dizzying thing that arrives and departs, you know, with somebody else. So even though I’m not a practicing person of the churches, those are things that I really actually do appreciate, you know, quite a lot.

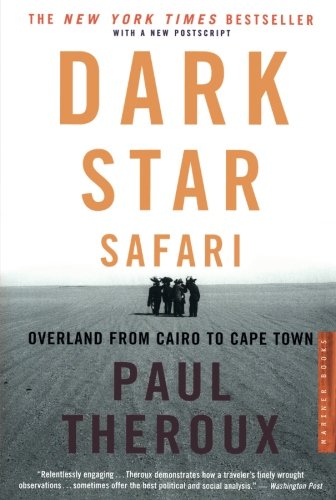

MS. TIPPETT: That’s very interesting. You know, I want to ask you, have you read Paul Theroux, the travel writer, and I guess he’s also a novelist?

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Have you read his book Dark Star Safari?

MR. WAINAINA: Yes. Up to page 300 or so. I got tired.

MS. TIPPETT: I read the whole thing. I wanted — that book actually got me thinking about this in a new way.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Now I know Paul Theroux has his own angle on things.

MR. WAINAINA: Sure. Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: But here he was, a Westerner, who in fact had been in — where had he been, Uganda, I believe — in the 1970s. So he was also — he was not just traveling all the way from the top to the bottom of Africa, but he was going back to particular places that he’d known well.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And he was very appalled at how — it was just anecdotal from his personal experience with all these decades of aid things hadn’t gotten better.

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I just want to read you — you know, there was a story that I thought was really — you know, this was the kind of story he told all the way through the continent about …

MR. WAINAINA: Correct.

MS. TIPPETT: … for example, being in Ethiopia and there’s a leper colony a German NGO had come in and built these beautiful condos that were totally not responsive to the way people lived and so the only slum-like place there were these German condos, which were falling down. And then he was in Uganda, where he’d been in the ’70s, where your mother is from, and he said — so here’s a passage.

“There’s a new hospital donated by the Swedes or the Japanese, a new school funded by the Canadians, a Baptist clinic, a flour mill that was signposted ‘a gift of the American people.’ These were like inspired Christmas presents, the sort that stop running when the batteries die or that break and aren’t fixed. The projects would become wrecks, every one of them, because they carried with them the seeds of their destruction.”

Do you think that’s right? And if it’s true, do you know — in your words, how do these projects carry the seeds of their destruction?

MR. WAINAINA: Well, I mean, it’s a complicated thing, but when we were speaking about the church, for example …

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. WAINAINA: … I mean, this certainty that if there’s a parish in the middle of Sudan, that parish is a permanent enterprise, right?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. WAINAINA: And it’s a permanent enterprise that is a part of people’s lives like going to get an ID and going to go to school is.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WAINAINA: And therefore, there’s not an extraordinary leap of faith to say, ‘I’m going to the Catholic church, clinic, mission, school, et cetera.’ These become part of the organism of your daily life. But if you go to, say, a sleeping sickness hospital that’s dropped in the middle of Sudan …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … with all these high-tech things and all these doctors flown in, just the sheer energy and effort of 12 four-by-fours, running up and down to buy food, and doctors falling sick all the time and saying, ‘This is a terrible posting. I prefer Mogadishu,’ and disappearing …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … and then the fact that it may have project funding for eight years for the mysterious and complicated way that project funding happens …

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WAINAINA: … and somebody signing off on it somewhere who is just like, ‘Well, you know, there’s a new government in France. I don’t know if we can approve the budget anymore.’ And I’m speaking of a lot of specific things, because I did visit a specific hospital and when I asked the question, ‘What’s going to happen? What’s the leaving plan?’ There was confusion because there was just like, ‘We actually are the victim of some decision up there and we don’t have a plan to say who we are going to leave it to should it come to where we are like we have fulfilled our objective and now we are leaving.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And then you had a question as well that you have all this high tech and you have all these people who would normally be paid quite high salaries, but the rules of the proposal and the setting up of the thing were that it would not provide basic health care needs. So you have a county hospital, which could not give people basic health care, and you have this hospital for sleeping sickness with 80 beds, which are not full and it couldn’t do that. So, you know, I mean, I went and visited this place and I did feel that that hospital was doing amazing work. There was no question in my mind. Sleeping sickness is a crisis. Nobody’s doing anything about it, and the crisis is massive, because there’s no drugs, there’s no water. I mean, for them to go there, set this up, find a system, is remarkable. But then you leave saying what’s going to be the picture in the long run? I mean, will they just tick it off and say the German government helped and then you move on?

Now, if this was something to do with, let us say could be for example the Catholic Church, so there’s a place in which there’s a relationship that can grow, that does not allow for things to get out of control or become dizzying or become stupid. There are checks and balances. So the problem there becomes that the environment and the reason that hospital lives is that it can. If I’m the German government and I want to build a hospital anywhere in Africa, people would be like, ‘Here. What color do you want it?’ So you don’t have any scrutiny that allows you …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … to be as disciplined as you could be.

MS. TIPPETT: Kenyan writer and journalist Binyavanga Wainaina. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Ethics of Aid: One Kenyan’s Perspective.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I want to change gears a little bit. You received a letter last year informing you that you had become a young global leader of 2007 of the World Economic Forum, and this letter invited you to a gathering to be part of a unique — I’m quoting now, “unique worldwide network of peers with a highly visible opportunity to significantly impact world affairs.”

MR. WAINAINA: [Laughs] Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, it is a great honor and you turned it down. I want to read a little bit from the letter that you wrote. “Some things were immediately clear to me from the letter and from the Web site, the quality of the letter’s paper, the gigantic networks of spectacular résumés on offer: the princes, princesses, the beauty queens and violinists, the presidents, the iconic athletes, Hollywood comedians, the artists, the various savers of various troubled societies.” But you said that it was not at all clear what would happen, that it was unexplained. And you said, “I assume that most like me are tempted to go anyway, because we will get to be validated and glow with the same kind of self-congratulation that can only be bestowed by very globally visible and significant people.” But you talked about how for you as a writer it’s important to “avoid things that give me too much certainty about one’s place in the world, about the world, about the perpetual shifting nature of characters and their interaction with each other and with space and time.” And you wrote, “It would be an act of great fraudulence for me to accept the trite idea that I am going to significantly impact world affairs.”

You know, what you’re doing there is questioning what looks important and powerful, not just from the perspective of the World Economic Forum, but from the perspective of a lot of people just who read newspapers and inhabit the contemporary world. Is that you? Is that your generation?

MR. WAINAINA: I hope so. I mean, I think I felt at first — I wrote that letter partly, because I was feeling like being mischievous.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WAINAINA: And I guess as somebody who has never had the most amazing relationship with institutions in my life, I really deeply resented the attitude within which they approached me for this thing, because I just opened my inbox and then there was this flood of people who were saying congratulations. And then I received this letter which says you are already this thing.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: I mean, it’s not clear or coherent to me what it is that they feel is going to give you world power.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: As far as some people on the other side of the political argument are concerned, it’s just a way to give themselves good PR because of the World Social Forum. I don’t even know and those politics are not mine. But the long and the short of it was I feel like if there’s a valuable thing about being a human being, it’s to never let your noble good be corrupted. And there are many things that I am, some of which may be disorganized or crazy, but I am, more than any other thing, I am a writer. It’s a thing I love to do. And I think that the writer’s role is to be something to society, to be some kind of free agent who allows to look for things, to have insight, to be able to say things sometimes that people are not prepared to say them. And that’s a thing that you need to protect, and it’s worth more than anything. I think that if a readership who reads my word on the continent and elsewhere trust that, trust that noble good, I feel strongly that you have an ability to speak to people and for people not to receive your words cynically.

Following the Obama campaign has really been a revelation, and I found myself really emotional the day after he won. And when thinking about it, you know, leaving alone the fact it’s the first black president, or anything else, it was like when was the last time somebody was just not cynical?

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Not cynical. Right. Yeah.

MR. WAINAINA: Just like you can do good. You are good people. We are good people. Like, not to be cynical. And I think it’s something that really sneaks up on you. And I think that if there’s such a thing as a global mood, I think the global mood is very cynical and positioning and then, ‘Well, I’m doing that but what about my CV?” And there’s all of these things and what your noble good is, what sense of service you come to the world to bring, somehow kind of disappeared. I mean, really, I’m kind of starting to hear a language that I haven’t heard since I was a kid in a way. What is your noble good? What do you serve? We’ve come to a point where we didn’t even believe that a human body could come together for an idea of a common good.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Let me ask you this. One of the things you write about is how, again, coming back to this phrase “the ethics of aid,” the donor aid, the shape aid projects take, and the spirit of them often really is saying more about Westerners’ guilt …

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … for example, and good intentions, again, is more responsive to one’s own desire to make a difference, to help, than it is in fact responsive to the needs of the people who are being helped. I mean, let me ask you this. Like, I spoke in the last year with a very important religious leader in this country who …

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … has in mid-career discovered AIDS in Africa and poverty in Africa and, you know, the story plays itself out again and again. And so here’s what he said to me. This is how he described his realization. He said, “The reason there are hungry people in the world, there are suffering people in the world, is because of our own selfishness. What do I say to a woman in Sudan holding a baby who’s dying of lack of water? The only thing I can say is I am sorry, I am sorry. Why did I not get here sooner?”

MR. WAINAINA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And I wonder if you could be sitting with him when he had that moment of realization, how would you want to nuance his reaction or his thinking about how to put that reaction — how to turn that into a project?

MR. WAINAINA: Oh, dear. I mean, I guess the thing would be first to say that, I mean, the fact of things is that a lot of the things that go on in the poor parts of the world come because of a particular sensibility and a particular greed and a particular determination for a particular kind of lifestyle, which sometimes has direct costs on the people in Africa or India or anywhere else. Certainly that’s true. Certainly we don’t live in a fair world. And certainly we’re not getting a fair shake. You know how global resources are allowed and more opportunities are created for people trying to do things. So I agree with that, certainly. But the point about all of this is that, like he says, a lot of people arrive in Africa to assume that it’s a blank empty space and their goodwill and desire and guilt will fix it. And that to me is not any different from the first people who arrived and colonized us. And I just want to reemphasize that this power is just about as dangerous as hard power.

MS. TIPPETT: This power to help, you mean?

MR. WAINAINA: This power to help.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. Is just as bad, as dangerous as hard power.

MR. WAINAINA: Certainly. Certainly. Because very often it arrives with a kind of zeal that is assuming ‘I will. I will do it. I will solve it for you. I will fix it for you,’ you know, and it rides roughshod over your own best efforts. To me the good efforts that have been done have been the ones that have been sensible and worked. You know, I was a child of parents who earned a good income, who was born in a public hospital in Kenya in Nakuru.

MS. TIPPETT: So that is possible.

MR. WAINAINA: When I was sick we’d go there.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And they would be like why spend the money on a private doctor when this is working? You know, these were things that worked. They were not big, they were not flashy, and it just is you keep moving to these things that are not sensible. And I think the fevered idea of saving something, to me is already so removed from something sensible.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. The fevered idea. I think …

MR. WAINAINA: Because when you’re asked to make choices, to pick a job, I want to just help people. Are you going to pick a job that gives you the satisfaction, that says, well, in six months I’ll have saved 42 orphans? Or the things that usually work, which are the sensible things, which are like, well, these people don’t have basic health care. If you can make sure that you collect and build one brick at a time and dat-dat-dat-dat, so there is a permanent enterprise here, so really a lot of the things that end up satisfying that sort of guilt are what you call the quick fixes.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: The mad rush of attention and food drops and planes and cameras and photographs and liftings and takings and adoptings and all those dramatic things that just can make you say, ‘I was a bad person and now I’m good and I can get back to work.’

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: As I was preparing this interview with you, I looked over at my desk and I noticed that there was, you know, one of these big cubes of Post-It notes, sticky notes, and it said on the side “End global poverty. Faster.” We’re surrounding ourselves now in this culture with these kinds of messages, which, again, are good messages, but there’s something so wrong with it as well.

MR. WAINAINA: Yeah. Yeah. Well, I mean, the quests and the causes are noble and I guess the things is, you know, I’m not a development economist and a lot of the things that I say, you know, I really don’t know the intricacies of things. In a sense I speak very much as a citizen …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … who’s witnessed this phenomena coming into our lives and looking at them and, you know, have my piece to say. And if there’s a thing that the West should know, it’s that where these things work is where people do them themselves. I mean, if you want to talk about grassroots organizations that work and change a country, you go to India, because they pretty much do them themselves. And because they have really no shrift for the usual nonsense. And the thing about Africa is it may be that we are poorer or weaker somehow so people with the craziest ideas, I mean, things that they tell their cousins they want to do they’ll be like, “You’re crazy …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: … you can do it and you can get money.’

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WAINAINA: And so I would just say for my own mind whenever I am looking at something and I want to know is this something sensible, I ask myself what kind of relationship does it have with the existing intelligentsia back in that country. If they participate in it, work for it, are involved in it, I probably tend to move in its direction. And if they don’t, I probably tend to move aside from it. If there is no engagement with it. I don’t know; it’s a rule of thumb. I don’t have any particular easy rationale for it. But I do know that there is an intelligentsia in Kenya who’s smart and who’s concerned about that country.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: And who takes time to know things. And if they’re not really interested in what you’re doing, I would doubt your motives or efficacy.

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote at the end of your piece that you wrote in 2007 — in Vanity Fair you wrote: “We have learned to ignore the shrill screams coming from the peddlers of hopelessness. We motor on faith and enterprise with small steps on hope and without hysteria.”

MR. WAINAINA: True. I’ll say again, you go back from 1940 until now. Any countries that have done well for themselves and have managed to do positive things and that have changed the lives of large parts of their countries have done so on their own effort.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WAINAINA: On the effort of their own citizenry with ideas that come from that citizenry and therefore get all manner of support from government or from all kinds of other places. That’s the way it works. There may be a place in the sense that, like, you have international cults, you have kind of international humanitarian movement, because you have situations that are urgent. Darfur was one. Rwanda is another.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WAINAINA: Certainly those things work, but the willy-nilly-ness of all of this is unacceptable. And our countries are frail and young and I have no problem being viciously aggressive towards these things that refuse to be accountable, because the stakes for us are very high. You know, you come, you do your three years, you go back. But for us the stakes are really high. It’s our life.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Binyavanga Wainaina is editor of the Kwani? literary journal and a visiting professor of Africana Studies at Williams College in Massachusetts.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: You can hear more of Binyavanga Wainaina’s point of view in my unedited interview with him. Download the MP3 of our full conversation and this complete program at speakingoffaith.org. This conversation is the beginning of an occasional series exploring the ethics of global aid. In the coming months, we’ll be offering other voices on this complex and wide-ranging topic, and we’d love to know what additional perspectives you’d like to hear and any wisdom you’d like to offer.

And my producers and I have spent this summer in correspondence and conversation with Muslims across the U.S. and the world. They’ve opened up to us on life, love, making art, and practicing law, on raising children, and contemplating the future. They have surprised, delighted, and challenged us as they will you. We’ll begin to bring them to the air with Revealing Ramadan, during the week of September 11th. And at speakingoffaith.org now, you’ll find small gems of Ramadan stories that you can download and an interactive map so you can explore the complex, rich reality of being Muslim in our time.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck, Nancy Rosenbaum, and Marc Sanchez. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with Web producer Andrew Dayton. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections