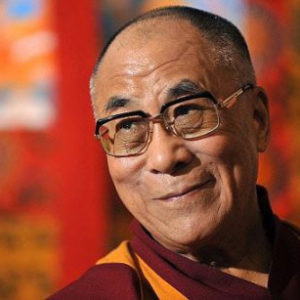

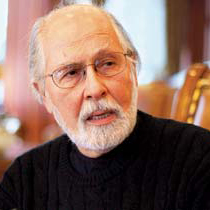

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, Jonathan Sacks, Katharine Jefferts Schori, and Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Pursuing Happiness

The XIV Dalai Lama seems to many to embody happiness — happiness against the odds, a virtue that is acquired and practiced. Before a live audience in Atlanta, Georgia, Krista had a rare opportunity to mull over the meaning of happiness in contemporary life with him and three global spiritual leaders: a Muslim scholar, a chief rabbi, and a presiding bishop. An invigorating and unpredictable discussion exploring the themes of suffering, beauty, and the nature of the body.

Image by Bryan Meltz, Emory University Photo/Video, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Katherine Jefferts Schori is the 26th Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church. She holds a doctorate in oceanography.

His Holiness The 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet is the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet. He is the author of many books, including Ethics for a New Millennium.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr is University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University. He's a prominent philosopher and scholar of Islam who has written many books, including The Heart of Islam and Man and Nature.

Jonathan Sacks was Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth for 22 years. He taught and spoke all over the world, with appointments at King’s College London and at New York University and Yeshiva University in the U.S. His many books include The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilizations, The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning, and most recently, Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times.

Transcript

September 25, 2014

JONATHAN SACKS: It is true that if you read Jewish history, happiness is not the first word that comes to mind [laughter]. We do degrees in misery, advanced guilt, and yet somehow or other, we get together and we celebrate.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR: There is a very deep nexus between beauty and happiness. And happy is the person who realizes inner beauty.

KATHARINE JEFFERTS SCHORI: Blessing each moment of the day. Blessing the milking of the cow. Blessing the covering of the fire at night. It’s that awareness and attending that I think is so significant.

HIS HOLINESS THE 14TH DALAI LAMA: The very purpose of our life is for happiness. The very purpose of our existence is for happiness.

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: His Holiness the Dalai Lama of Tibet seems to many the very embodiment of happiness — happiness sustained against the odds. And so it was a rare and fascinating opportunity to sit down with him and three other global spiritual leaders and to muse over this subject. The pursuit of happiness is something Americans call a right, but what do we know about happiness as a spiritual practice? What does it have to do with our bodies? What is the resonance between happiness and virtue, happiness and beauty? The Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church of the United States, the former Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, and an eminent Muslim scholar join the Dalai Lama in illuminating these and other questions.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: “The Interfaith Summit on Happiness,” as it was called, was convened by the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University in 2010. It took place before 4,000 people in a basketball arena transformed by flowers and by the festive energy that does seem to follow His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet wherever he goes. The court was decked with black carpet and white chairs. Monks sat on cushions alongside an incandescently lit stage. The Dalai Lama sat next to his translator, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, and conferred with him constantly, as you’ll hear. Joining them were Seyyed Hossein Nasr of George Washington University, the Most Reverend Dr. Katharine Jefferts Schori, and Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks.

MS. TIPPETT: So I’d like to ask each of you one question and then have us interact. And if you have questions of each other, I’d also welcome that. Your Holiness, as several people have already mentioned, you radiate happiness. You seem to embody happiness and you also have a wonderful sense of humor. And yet, you are familiar with suffering. Your life has unfolded on a canvas that is marked by gravity and the fate of your people and your tradition. So how does your understanding of happiness, your notion of happiness, encompass suffering and the hardness of life and speak to that?

THE DALAI LAMA: Of course, my life not easy. That is clear. I think perhaps — I think firstly when I see some problem, some tragedy, I always look from different angle. And sometimes a tragedy, one aspect tragedy, but that same event may also may have some positive thing. So when I look more holistically, then that event not 100 percent so negative. There are also part of positive.

Now one example, I usually telling people we lost our own country, itself sad, but that brings different and new opportunity; there’s immense benefit. Sort of like that there’s one thing. Second, when we face some sort of sad thing, if you look very closely and it looks unbearable, look from distance. There’s not that much that’s unbearable.

Then another thing, as one Buddhist master — eighth century — mentioned, when we face some problem, think or analyze the problem, situation. If the situation can overcome eventually, then no need worry. Make effort. So these things I usually do. And also, if a friend spend I think one week together, then you may notice a certain period my sadness [laughs] or with my anger some time also due to some irritation. That also as a human being is impossible. But overall, OK. [laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: And I think it can be very interesting for this next hour or so if we not only honor and enjoy the echoes of similarity, but also the differences. So I wonder — and I pose this to you, Rabbi Sacks, it seems to me that the Hebrew Bible, let’s say the Psalms, really wallow in sadness and suffering and anger as a way through those human experiences. So I wonder how do you respond to this idea and how might you see it differently or what might you add to that approach to sadness? And, Rabbi Sacks, I know that you have just finished sitting shiva at the death of your mother. So you’ve been in a period of grief and mourning, which is very much lived and embodied.

RABBI SACKS: Yeah. It is true that if you read the Jewish literature and you read Jewish history, happiness is not the first word that comes to mind [laughter]. We do degrees in misery, post-graduate angst, and advanced guilt, and we do all this stuff, you know. And yet somehow or other when all of that is at an end, we get together and we celebrate. And where I love what His Holiness has just said, how he himself has lived a story that I resonate with, the story of suffering and exile, and yet he has come through it still smiling. And that to me is how I have always defined my faith as a Jew.

The definition of a Jew, Israel is at it says in Genesis 34, one who struggles, wrestles, with God and with humanity and prevails. And Jacob says something very profound to the angel. He says, “I will not let you go until you bless me.” And that is how I feel about suffering. When something bad happens, I will not let go of that bad thing until I have discovered the blessing that lies within it.

When my late father died — now I’m in mourning for my late mother — that sense of grief and bereavement suddenly taught me that so many things that I thought were important, externals, etc., all of that is irrelevant. You lose a parent, you suddenly realize what a slender thing life is, how easily you can lose those you love. Then out of that comes a new simplicity and that is why sometimes all the pain and the tears lift you to a much higher and deeper joy when you say to the bad times, “I will not let you go until you bless me.” Thank you.

[Applause]

MS. TIPPETT: To that word “blessing” and “blessed,” Bishop Jefferts Schori, you talk about the many words in Christian tradition, in biblical Greek, that add up to happiness, and blessing is one of those. And yet I think — yes. So, Rabbi Sacks, you’ve also written about the Oy Vey theory of Jewishness [laughs]. And I think there’s been a temptation in Christianity — not a temptation, a tendency, to think about happiness that will only be complete after this life, right? In the pure unmediated presence of God. Talk to me about how you work with that tendency and how you see that evolving in the imagination of Christians now.

BISHOP SCHORI: There’s this ongoing tension between seeing happiness as joining with God, as communion with God, that’s only possible in the afterlife, and the insistence that human beings are created to be happy, that happiness is possible in this life. There’s the particular piece of Christianity that insists that sometimes suffering is a route to happiness for the larger community. That kind of suffering may not be chosen, but it contains blessing within it. The sense that our goal is this fully restored creation at right relationship with all that is and sometimes the journey there requires us to enter into suffering and to demand, to insist, that there is blessing in the midst of that, wrestling with the angel. It must be there. You have created us to be happy, you have created us to be good, now show us. Show us the way through this. Show us the possibility for which all that is is created.

MS. TIPPETT: Professor Nasr, it seems to me that a distinctive word that Islam brings to this discussion of happiness, happiness and virtue, is the notion of beauty. You’ve written a great deal about that, and I’d love for you to say a little bit more about the link you understand between beauty and virtue and happiness.

DR. NASR: First of all, in the Arabic language, the word for beauty and virtue is the same, and goodness, all three. The root which is also the root of my own name, my name is Hossein, now made famous thanks to your president — your president, everybody knows it. The root “hsn” in arabic, means these three things: beauty, virtue and goodness. In the Islam — Muslim mind, they’re not separated from each other. In the deepest sense, goodness — in the ordinary sense, these were external actions. In a deeper sense, virtue is within us. Beauty can deal also with external forms and it can deal with beauty of the soul, beauty of the spirit, within us. But beauty in a sense is more interiorizing. Beauty is what draws us directly to the Divine, to the Divine reality. It’s presumptuous to talk in front of His Holiness about Buddhist sayings, but the Buddha says that the beauty of my image saves. So the beauty of celestial beauty that is the center of the sacred art of various traditions is salvific. It’s a way of salvation. And ugliness, which is the opposite of beauty, in Arabic, also means evil. The ugly is the evil. One of the signs we live in an evil world is the ugly ambiance we’ve created for ourselves.

And look at the remarkable predominance of beauty in nature. Take us human beings out and look at nature. Remarkable predominance of beauty, from the fish that swim under the sea in coral reefs that we’re now destroying so rapidly in the Gulf of Mexico to the great mountains whose snows are melting, thanks to the fact that we’re driving too many cars. I think what is happening is proof precisely of the error of our worldview. When we look at nature, look how beautiful it is. Now, Islam looks upon this call — the beauty, as not being something accidental. To be virtuous is to be beautiful. To be good is to be beautiful. And that is why wherever Islam went, it created a civilization based on beauty. Look at Islamic art, the carpets, the tile — and that again is one of the great tragedies that we have now some of the ugliest cities in the world — of the Islamic world. The great contrast. Even a city like Isfahan and it’s modernized part of Karachi or Cairo. They’re all part of the same civilization. But the spiritual aspect of beauty has not disappeared with the ugliness of urban sprawl. It is central to Islamic spirituality and Islamic spirituality sees even morality in terms of spiritual beauty. We’re created in beauty. We’re drawn to beauty and our soul is drawn to beauty. So, yes, there’s a very deep nexus between beauty and happiness, and happy is the person who realizes inner beauty.

[Applause]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with a public conversation between the Dalai Lama, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Episcopal Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori, and Muslim scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve noticed in some of what you’ve all written in preparation for this conference — the monotheists among us here on the panel — that there is a lot of attention to defining happiness and to the many words that are used in our different traditions and in our languages, in our traditions’ original language. It makes me think that, in this culture in particular, if we are going to take happiness seriously in a whole new way as I think many of us want to, we do have to wrestle a bit with that word. That also leads me to wonder if American culture has somehow been fundamentally led astray from the outset by defining happiness as a right. Your Holiness, I wonder how you react to happiness being defined as a right?

THE DALAI LAMA: Well, it does with a right.

MS. TIPPETT: Sorry? You do.

THE DALAI LAMA: We’re right.

MS. TIPPETT: Right? You do [laughs].

THE DALAI LAMA: I always believe and also share with the people, the very purpose of our life is for happiness. Those nonbeliever also they felt that religion — religious faith is a — brings a lot of sort of complication. So without that, they feel the easier to achieve happy life. So I think the very purpose of our existence is for happiness. So that mentioned, your Constitution. And then also is equally their right. You see, happiness not come from sky, but we must make a happy life. So we have a responsibility. The government cannot provide happiness. Happiness must create within ourselves and our family. So ultimately, our own responsibility, isn’t it?

BISHOP SCHORI: Happiness, is not a right, but a duty, and a duty not just to one’s self, but to the whole community, to the whole of creation. When we see it primarily as a right, it is so individually focused that at least many Americans lose the perspective of the larger whole. Right to pursue happiness on behalf of society, on behalf of all creation.

MS. TIPPETT: Rabbi Sacks?

RABBI SACKS: I’d like just to reflect on one other word, which is “pursuit.” Finding happiness doesn’t necessarily follow from pursuing it. Sometimes the deepest happiness comes when you’re least expecting it. And there is a wonderful story about an 18th-century rabbi, Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, who is looking at people rushing to and fro in the town square. And he wonders why they’re all running so frenetically. He stops one and he says, “Why are you running?” And the man says, “I’m running to make a living.” And the rabbi says to him, “How come you’re so sure that the living is in front of you and you have to run to catch it up? Maybe it’s behind you and you got to stop and let it catch up with you.” Now which bits of contemporary culture do we stop and let our blessings catch up with us? Now that is called the Sabbath, which we all share.

[Applause]

The Sabbath is when we celebrate the things that are important, but not urgent. And I remember once taking, you know, an atheist — I think an atheist who’s the premier child care specialist in Britain to see a little Jewish primary school and some of the stuff they do there. And she saw on Friday, you know, the little children preparing for the Sabbath, the little five-year-old mother and father blessing the five-year-old children and welcoming the five-year-old guests. She’s fascinated by this Sabbath, which she has never experienced. And she asked one five-year-old boy, “What do you like most about the Sabbath?” and he says — or “What don’t you like?” And the five-year-old boy, being an Orthodox child, says, “You can’t watch television. It’s terrible.” [laughter] And then she said, “What do you like about the Sabbath?” and he said, “It’s the only time daddy doesn’t have to rush away.” Sometimes we don’t need to pursue happiness. We just need to pause and let it catch up with us.

[Applause]

MS. TIPPETT: And I think that gets at precisely why the practice of meditation, the teachings of Buddhism and the teachings of His Holiness in particular, have been so magnetic for so many people in the West as they have discovered this. There is at the heart of Buddhist teaching a notion about happiness, finding calmness in the mind, is part of it, which is something you just pointed at. And I’d like to draw out the three of you about corollaries in your traditions — obviously Sabbath is one — for generating calmness of the mind.

DR. NASR: Of course, in Islamic tradition, the five daily prayers themselves. You pull yourself out of the flow of time in a space that is sacralized, and ablution itself in a sense washes the soul as well as the body. And for a few minutes, even if your mind is running like that, you have to force yourself to pull yourself out of that context. Of course, only the saints succeed completely. But nevertheless, the exercise has a tremendous effect upon our having at least certain punctuations put upon this sentence of our life every day that goes faster and faster.

And secondly, of course, the month of Ramadan, the month of fasting, in which during the whole month, the tempo of even big cities slows down. Around 6:15 or 6:20 when the sun sets, you go to such a big city as Cairo or Karachi where the streets are cluttered, you can’t drive. All the streets are empty. Everything slows down. And this power of Ramadan has been able to preserve despite everything.

I think — of course, you have, for example, you used to have Lent and you have, of course, Yom Kippur, the holy days of Judaism, where we share that. But in Islam, you have a whole month of fasting, which changes the whole tempo of life and the daily prayers. They’re very, very centered. They’re like Buddhist meditations in Islamic form by coming in a punctuated manner throughout the day. And, of course, some people then have more extended prayers. We have our own form of meditation, invocation, contemplation, but that’s only for people who are spiritually very active, you might say, like, let’s say monks in Tibet. But for the ordinary Muslims, those other practices are ubiquitous. They run throughout all of society.

RABBI SACKS: Obviously, in Judaism, as in all the religious traditions, there are elite forms of meditation. But what really interests me, as interests you, is just the simple basic act of prayer. And prayer for me, daily prayer — three times daily. We’re not quite up to five times daily [laughter] — but we’re impressed. Three things happen when I pray. The first thing is thanks. You know, the first prayer we pray, “Thank you, God, for giving me back my life.” The second thing is confession. You feel the ability to acknowledge your mistakes, then you grow, you learn by this. So that is the second thing. And the third thing is simply the basic experience of prayer altogether, standing in the presence of a deeper form of being, knowing that this universe is not indifferent to my existence, deaf to my prayers, blind to my hopes. And when I feel in that presence of the being at the heart of being, then we experience the greatest line of all in the life of faith from Psalm 23, “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me.” We can face the future without fear if we know we do not face it alone.

MS. TIPPETT: Bishop Schori?

BISHOP SCHORI: We share many of the same forms of prayer — prayer as awareness and attending. Christians, it may happen in other traditions as well, sometimes pray with images, sometimes pray without images, a kind of emptying prayer. I think the part that is perhaps most attractive to new learners is about understanding all of existence as prayer. The Celts were very effective at blessing each moment of the day, blessing the milking of the cow, blessing the covering of the fire at night. Brother Lawrence blessed the washing of dishes. Runners begin to understand the blessing that comes with putting your body to work and emptying the mind. There are practices that each of us participates in that are about simple awareness of God’s presence in every breath, in every moment, in every encounter, in every challenge. It’s that awareness and attending that is, I think, so significant.

[Applause]

DR. NASR: I agree with you completely, and they are also very much emphasized in Islamism and Judaism priesthood and is divided among all human beings and each person stands directly before God. But perhaps there is one thing that the rabbi doesn’t know and, as one doesn’t know, I should mention the Muslims owe a great deal to Moses. You say you pray three times a day, we pray five times a day. We believe that, when the prophet ascended from Jerusalem to heaven, God taught him the daily prayers that we perform. And when he was coming down, Moses met him and said, “How many units of prayer did God order you to tell to your followers?” He said, “51.” He said, “They’ll never do it. Believe me, I have a thousand years experience. Go back and bargain with God.” [laughs] “Go back and bargain with God.” So the prophet went and bargained and it came down to 17 units. Thank you very much. Otherwise, we’re going to have to do 51. So Muslims are always thanking Moses for that. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again, and share and watch this entire two-hour conversation at onbeing.org.

[Music: “Glitch Perfect” by Andy McNeill]

MS. TIPPETT: Coming up, more of the “Summit on Happiness,” with the Dalai Lama and other religious leaders. We explore their somewhat different takes on where the body comes into spiritual life.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Glitch Perfect” by Andy McNeill]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: a conversation about the meaning of happiness, with His Holiness The Dalai Lama of Tibet and three other global spiritual leaders: Muslim scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori of the Episcopal Church, and Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, former Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth.

Emory University convened this gathering. It unfolded before an audience of 4,000 people in an athletic complex that was transformed by light and by flowers in the maroons and golds of the Dalai Lama’s robes.

MS. TIPPETT: Where does the body come into all of this? Where does the body come into happiness? It can sound like we’re having a discussion about happiness that’s very cerebral, very mental. You, for example, Bishop Schori, have spoken about running as body meditation. Let’s talk a little bit about our physical selves in this condition of happiness.

BISHOP SCHORI: There are two essential pieces to that. One is the ancient ascetical tradition that trains the body so that the mind can in some sense do its work more effectively, the mind and the heart and the soul. And the other is this sense that I will speak of in my own tradition as incarnation. Our bodies are a blessing. They are evidence of God’s love for what is created. The sense of happiness of the whole creation, Shalom, the reign of God, is about bodily needs satisfied. People have enough to eat, they have shelter, they have meaningful work, they live in peace, they can watch their children grow up and the elders can wander in the street. It’s both. It’s both understanding bodies as tools for working toward happiness, for working toward justice and peace and that justice and peace and embodied blessing needs to be available to the whole community.

RABBI SACKS: Well, obviously, Judaism has a certain approach to the physical dimension of the spiritual life. It’s called food. [laughs] In fact, somebody once said, you know, if you want a crash course in understanding all the Jewish festivals, they can all be summed up in three sentences: They tried to kill us. We survived. Let’s eat. [laughter] But I think that is part of our faith that God is to be found down here in this world that God created and seven times pronounced good. And I find one of the most striking sentences in Judaism — it is in the Jerusalem Talmud — is the statement of Rav that in the world to come, a person will have to give an account of every legitimate pleasure he or she deprived themselves of in this life, because God gave us this world to enjoy.

I must say that quite apart — and I mean, absolutely, Judaism has taken — I think we share this, but Judaism has said there are three approaches to physical pleasure. Number one is hedonism, the worship of pleasure. The number two is asceticism, the denial of pleasure. And number three is the biblical way: the sanctification of pleasure. And that, I think, is important and very profound. And I must say that, you know, sometimes the best kind of interfaith gatherance — I mean, theology is extremely wonderful. It’s very cognitive. That is a very polite English way of saying boring. [laughter] And sometimes the best form of interfaith is you just sit together, you eat together, you drink together, you share one another’s songs. You listen to one another’s stories and just enjoy the pleasures of this world with people of another faith. That is beautiful.

I would add just one other thing. If there is one thing I find beautiful beyond measures — it’s there in my own tradition in what we call hachnasat orchim, hospitality, very real element of Christianity and Islam and Buddhism — it’s a super element in Sikhism, what’s called langar. You know, it’s not just my physical pleasures. It’s giving physical pleasure to those who have all too little. And one very great Hasidic teacher once said, “Somebody else’s material needs are my spiritual duties.” And that, I think, is where we join in sharing our pleasures with others

[Applause]

DR. NASR: The body, in a sense, is like a double-edged sword. There is no religion without asceticism. That’s impossible. However, to deny the reality of the body sanctified — what you call sanctification — is also a very great error. And as great tradition as Buddhism, which began by emphasizing [unintelligible] sacred body of the Buddha and we have that in another form in Islam. We have that in all Abrahamic religions, the fact that we believe in the resurrection of the body and not only of the soul, which Islam shares with Christianity and Talmudic Judaism. The question of the denial of the sickness of the body, which also has to do with sacred acts of sexuality and the relation that we have with the world of nature and the denial of the sacred aspect of nature they all go together, cluster together.

And to realize that our body is also has a sanctified aspect that is a projection of, in a sense, a subtle body, the spiritual body on this plane and especially physical beauty reflects sometimes that very, very deep beauty is not skin deep necessarily, and that spiritual beauty is always reflected in the physical. We grow it when we’re born. As a young man and woman, we might be beautiful, but nothing for that, that God has done that. When we’re old, if we’re still beautiful, it’s the reflection of our actions in this world. A person who grows old beautifully, there’s something inward that has been transformed. So the body is very, very precious. The care for it, the understanding of its significance and a deeper level of spiritual significance which [unintelligible] in the universe and we also have it Islam is, I think, a very, very significant revival of religious teaching that has to take place in all the religions today.

[Applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Your Holiness, I wonder how you think about the body. Where does the body come in to your imagination about spiritual happiness?

THE DALAI LAMA: Without a body then no longer brain [laughter].

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

THE DALAI LAMA: That difficult to think. [laughter] So from the Buddhist viewpoint, of course, there is a tradition which is based on law of causality. This is in thinking, analyzing is the most important. For that, human brain is really very smart. The other animals, they also, from the Buddhist viewpoint, they also have the feeling. Yet they have no such wonderful sort of brain. So therefore, we believe, we consider this body is something very precious.

GESHEN THUPTEN JINPA: For example, there are Buddhist practices that involve one’s relationship with an attitude towards one’s body, one’s material resources, and also one’s collection of virtues and in the connection to all of these one needs — you know, there are different stages of practice that involve, first of all, kind of letting go and then the second stage …

THE DALAI LAMA: … under different circumstances …

GESHEN THUPTEN JINPA: … under certain circumstances, we have to …

THE DALAI LAMA: … the circumstances are such, you see, give your body, your organ, something really benefit, then give. Other circumstances, you must protect.

GESHEN THUPTEN JINPA: Protect. So there’s a kind of a guarding and protecting and nurturing of the body and then also a perfection of those resources in body and then increasing and enhancing the capacity. So there’s a complex relationship, you know, with body resources and one’s virtues.

THE DALAI LAMA: And also, I already mentioned in the beginning, two different kinds of satisfaction. One satisfaction, of course, of comfortable shelter, sufficient food, and also sufficient sleep provides certain degree of satisfaction. That also we have to acquire. Nothing wrong. And comfort will sustain your body fit, then your mind, mental function, become more effective. Physically, too much tire and then mental function also difficult. So in a way, there’s some happiness, certain degree of happiness or satisfaction related with sensory types of body. And a level of happiness or satisfaction is a mental state. Between these two, mental state is more important.

I think, obviously, mentally happy even as you see some purpose, even your physical sort of difficulties now Ramadan is in daytime, whole day fasting. You may feel a little hungry or some sort of even tiredness, but mentally you voluntarily take that, that hardship, so that gives you satisfaction mentally. So mental satisfaction can subdue physical difficulties. Other hand, mental unhappiness, mental sort of pain, cannot subdue by physical comfort. So mental state is more superior, more important.

[Applause]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with a public conversation between the Dalai Lama, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, Episcopal Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori, and Muslim scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

MS. TIPPETT: Your Holiness, compassion is obviously central to what you teach and also to your understanding of a happy life. You have written and spoken a great deal about practicing compassion towards enemies, towards those who hate you. This is a moment in American political life and cultural life where there’s a great deal of hatred and lack of compassion of enemies, and I wonder, just to bring this discussion to another level, to a social level, what advice you might offer to this moment in our collective life?

THE DALAI LAMA: Jesus Christ …

GESHEN THUPTEN JINPA: For example, in the Gospel, you know, in the Gospel you find the commandment that, if some hit you on your right cheek, then turn the other cheek.

THE DALAI LAMA: So there’s this sort of same idea, practice of patience and practice of tolerance.

BISHOP SCHORI: Yes, but also subverting, subverting the violence, using the violence, in some sense, the energy of the anger to change the situation.

MS. TIPPETT: But what does that mean in practical terms? How would that look?

THE DALAI LAMA: That also similar, that also similar. Now here you see we have to go some more deeper level. The real demarcation of violence and nonviolence is not on the level of physical action, but mental action. Certain sort of physical action, wrongful action, are motivated by sense of concern of well-being of other. In order to stop their wrong doing, if they carry wrongdoing, ultimately they will suffer. So [unintelligible] that and purely the sense of concern of their long-term well-being, use some harsh method and forcefully stop their wrong doing. It’s nonviolence.

BISHOP SCHORI: Hitting on one cheek in the ancient world, the superior would hit with the back of the hand. And if you turned your head, he would have to use the other hand and look you in the face. So suddenly the dynamic has changed. He would have to see you. He can’t simply hit an inferior.

RABBI SACKS: There’s a line to me — in the 23rd chapter of Deuteronomy — so unexpected. And I want — I think we all have to hear it. Here it is: Moses is talking about the experience of the Israelites in Egypt. We read about it in the Book of Exodus, an age of oppression, of slavery, of almost genocide, attempted genocide. And eventually the Israelites leave. They go through the desert, and as they’re about to cross the Jordan and enter the land, Moses says these words: “Do not hate an Egyptian for you are a stranger in his land.” Now that language is very odd. You’re a stranger in his land sounds as if the Egyptians gave them hospitality, as if they put up the Israelites in the Cairo Hilton [laughter], and it wasn’t like that.

So what is Moses saying, “Do not hate an Egyptian for you are strangers in your land”? He is telling the Israelites that you have left the physical Egypt. Now you must leave the mental experience of Egypt. You have to let go of hate, because if you do not let go of hate, you will never be free. If the Israelites had continued to hate their enemies, Moses would have taken the Israelites out of Egypt, but he would not have taken Egypt out of the Israelites. They would be slaves to their past, slaves to their feeling of pain and injustice and grievance. This is the line he taught them and the line we have to repeat day after day in this difficult and dangerous 21st century. You have to let go of hate if you want to be free.

[Applause]

THE DALAI LAMA: One of my Muslim friend explained to me one interpretation of Jihad, not only sort of attack on other, but real meaning is combative attack your own wrongdoing or negativities.

DR. NASR: The greater Jihad, the bigger Jihad, is to combat your own negative forces within you. Yes, yes.

THE DALAI LAMA: So in that sense, the whole Buddhist practice is but practice of Jihad. [laughter]

DR. NASR: Exactly, absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: A great conclusion for us, an interfaith summit. [laughter] Yes. Professor Nasr, you’ve written that one of the Arabic words most commonly used for happiness literally means expanded. This follows very much on what His Holiness just said. Rabbi Sacks has written that, in the 21st century, all religious people must feel themselves enlarged rather than threatened by the presence of religious others. I personally feel that this discussion has been a wonderful demonstration of that. Of course, again, it is such an honor to be here with His Holiness and with all of you and I want to thank you so much and thank you all for coming, and this concludes our conversation.

[Applause]

[Music: “Dreamscape” by Tuatara]

MS. TIPPETT: His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, who was born Tenzin Gyatso, is the spiritual leader of the Tibetan people.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks is the former Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the British Commonwealth. He is now the Ingeborg and Ira Rennert Global Distinguished Professor of Judaic Thought at New York University and the Kressel and Ephrat Family University Professor of Jewish Thought at Yeshiva University. He has also been appointed as Professor of Law, Ethics and the Bible at King’s College London.The Most Reverend Dr. Katharine Jefferts Schori is the 26th Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church.

And Seyyed Hossein Nasr is University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

[Music: “Dreamscape” by Tuatara]

MS. TIPPETT: On our website you can listen again and share this episode. You can also watch the entire two-hour live event. That’s at onbeing.org. There you’ll also find our blog, which includes among other riches a weekly column by the Quaker elder and educator, Parker Palmer. Each week is a vignette on themes of our lives: from gratitude, deep darkness, and anger, to living an undivided life. He often ends with a poem to send you into the day. Look for Parker Palmer’s column every Wednesday on our blog, at onbeing.org.

[Music: “Knee-Deep In The North Sea” by Portico Quartet]

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Chris Jones, David Schimke, and Bekah Johnson.

Special thanks this week to John Witte, April Bogle, and Frank Alexander of the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University in Atlanta.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections