Luke Timothy Johnson and Bernadette Brooten

Deciphering the Da Vinci Code

The wildly popular novel turned movie reimagines the New Testament, in part, as a cover-up. What really happened in the fluid early years of Christianity? What is the truth about Mary Magdalene? We separate fact from fiction in the story’s plot with two New Testament scholars who say that the story is simpler and much more interesting than conspiracy theories suggest.

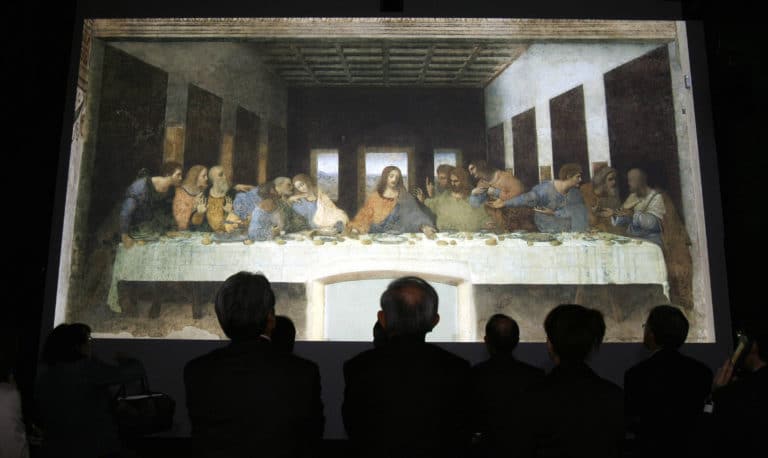

Image by Toshifumi Kitamura/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Luke Timothy Johnson is R.W. Woodruff Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins in the Candler School of Theology at Emory University, and author of The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation.

Bernadette Brooten is Kraft-Hiatt Professor of Christian Studies at Brandeis University, and Program Director of The Feminist Sexual Ethics Project.

Transcript

June 1, 2006

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Deciphering The Da Vinci Code.” The wildly popular novel-turned-movie reimagines the New Testament in part as a cover-up. So what really happened in the fluid, early years of Christianity? This hour we’ll separate fact from fiction in The Da Vinci Code plot. I’ll speak with Luke Timothy Johnson, who knows the New Testament as well as any living scholar. He says the process by which it came to be is both simpler and more interesting than conspiracy theories can suggest. Also, recent scholarly discoveries about women in the New Testament world. It’s true that Mary Magdalene was not a prostitute, but the evidence suggests she was something far more liberated than a mistress.

This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

I’m Krista Tippett. The actor Ian McKellen is proclaiming now at a theater near you that the greatest story ever told was a lie. The Da Vinci Code‘s mix of fact and fantasy is dizzying. But this hour we take on some real questions it raises. Why were some of the ideas of early Christians included in the Bible while others were left out? And how did it happen that modern Christians inherited a false view of women in the early church, including Mary Magdalene?

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today, “Deciphering The Da Vinci Code.”

At the core of The Da Vinci Code plot is a secret, that Mary Magdalene was Jesus’ wife and the mother of his children. This, the story suggests, was covered up by early church authorities, but it was passed down through an elite society and encoded in a painting by Leonardo da Vinci.

[Excerpt from The Da Vinci Code]

MR. IAN MCKELLEN (AS SIR LEIGH TEABING): The Last Supper, a great fresco by Leonardo da Vinci. Now, mademoiselle, where is Jesus sitting?

MS. AUDREY TAUTOU (AS SOPHIE NEVEU): In the middle.

MR. MCKELLEN: Good. And what drink?

MS. TAUTOU: Wine.

MR. MCKELLEN: Splendid. And one final question: How many wine glasses are there on the table?

MS. TAUTOU: One, the Holy Grail.

MR. MCKELLEN: Open your eyes. No single cup. No chalice. Well, that’s a bit strange, isn’t it, considering both the Bible and standard Grail legend celebrate this moment as the definitive arrival of the Holy Grail? Ah.

MS. TIPPETT: We won’t take on all the details of The Da Vinci Code this hour. It mingles biblical history with lore about pagan worship, the Holy Grail and secret societies both ancient and modern. We’ll focus on gathering a basic picture of the fluid early centuries in which orthodox Christianity was defined.

Later, we’ll speak with feminist scholar Bernadette Brooten. A decade ago, she unearthed a true biblical cover-up of a female apostle whose name had been changed to make her male. First, Luke Timothy Johnson of Emory University. He’s known for examining the New Testament in theological, social, literary and historical context. Theologians have always learned about inconsistencies in the New Testament narrative, but Luke Timothy Johnson is critical of what he calls “the conspiratorial tone” of The Da Vinci Code and other popular works.

MR. LUKE TIMOTHY JOHNSON: The conspiracy theory says that Christianity was wildly diverse from the beginning with many different versions and that there was sort of a constriction down into a rigid uniformity. I think the history of the process of canonization is both simpler and more interesting than that.

MS. TIPPETT: The word “canon” is taken from a Hebrew and Greek word denoting a straight line to measure by. The 27 writings we know as the New Testament are meant to be a definitive measure of Christian teaching. They include the Gospels — four distinct narratives about the life of Jesus, as well as the book of Acts, stories about the early church. There are a number of letters from the apostle Paul to early churches and a handful of letters by other writers. And there was one apocalyptic vision, the Book of Revelation, which almost didn’t make it into the canon. There were many writings circulating among early Christians that didn’t make the cut. In fact, nearly 400 years passed after the life of Jesus of Nazareth before the North African Council of Carthage closed the Christian canon. I asked Luke Timothy Johnson what happened in those 400 years.

MR. JOHNSON: In the first place, communities of faith preceded the writing of scripture. So you had communities who believed in Jesus as the risen Lord who were handing on memories of His sayings and of stories about Jesus, which were gathered, eventually, into compositions.

MS. TIPPETT: And it was very much an oral culture, wasn’t it, for decades?

MR. JOHNSON: It was both oral and scribal. I mean, the two things tended to go together in antiquity. But the memories of Jesus certainly were handed on in oral form and usually in the form of individual anecdotes rather than sustained narratives. But what we find is that the writings of — that came to be called the New Testament, very early on, were used in the public assembly. They were written for communities and to be read out loud to those communities. And it was this process of getting a letter from the apostle Paul and reading it out loud in the assembly, together with reading some of the law and reading some of the prophets, that began to establish Paul’s letters as scripture. That is, as something powerful and authoritative.

The next step toward canonization was a very natural and organic one, which was that communities began to exchange their writings. “Oh, we have a letter from Paul. Would you like to read it? And let us read your letter from the apostle Paul.” And as a result of that natural process of exchange, communities began to read each other’s mail, in effect.

MS. TIPPETT: Are we still talking sort of first century and…

MR. JOHNSON: Absolutely. Very early on. Already in — by the ’80s and ’90s of the first century. What happens when communities begin to read other people’s mail is that they have a larger sense of the church than they had when all they were reading was Paul’s letter to them, for example. Or when the community that had John’s Gospel written for it now became aware of Mark’s Gospel, which is quite a different rendering of Jesus, they have an enlarged view of who Jesus might be. This process seems to have gone on for 70, 80 years, until about the middle of the second century.

MS. TIPPETT: Luke Timothy Johnson.

Around the middle of the second century, something of a crisis developed. A plethora of new writings spurred Christian leaders to define which scriptures had authority. A challenge came from the Gnostic movement. Gnostic texts have become popular reading in our time. The term “Gnostic” comes from the Greek word for knowledge. Ancient Gnostics claimed that they were privy to secret knowledge about the divine. Gnostics who became Christian believed that the creator God of the Old Testament brought forth a flawed creation and that Jesus Christ revealed the existence of another, higher God.

Alongside Gnosticism were other influential movements. For example, in the year 170, an Assyrian-born philosopher named Tatian crafted a single Gospel out of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. He harmonized their differences away. Tatian’s work gained readers across the Christian world, but church fathers rejected it, as they rejected the notion that any Christian truth could be secret, known only to the few. And they begin to articulate criteria for selecting the books of the New Testament.

MS. TIPPETT:You make the point in your writings, and you said this to me a moment ago, that a key factor is not whether documents can be read or used by individuals, but whether they are to be read publicly in worship. I mean, what difference does that make? And, you know, what — then the question is, what difference should it make to us today that that’s how the documents came to be selected?

MR. JOHNSON: Well, we really do here come to the heart of the matter. The Council of Carthage in 397, which is one of our early canonical, or rather conciliar statements concerning the canon, says that only these writings should be read en ecclesia, that is, in the church. And then it lists all of the various texts that now form our Bible. The point of this public reading is that classical Christianity defines itself as a public institution. It is, if you will, a people. It has a sense of communal identity, which can be expressed in creeds, in certain scriptures, in — let’s face it — institutions, such as leadership and teachers and so forth.

The critical dividing line there then, in terms of which texts should be read in the assembly, are which ones build the church as a community, as opposed to which ones simply serve as edification for the individual. Many of the Gnostic writings, for example, are highly individualistic in character. They don’t even recognize the legitimacy of institution but rather are what we might call today spirituality. That is, they talk about, you know, how to free oneself from the body’s trammels and this sort of thing.

MS. TIPPETT: Which is possibly why they appeal so much to modern people who are so interested in spirituality.

MR. JOHNSON: You got it in one, that spirituality today tends to be defined as sort of a cultivation of the self. And why this — why we are revisiting the second century, which is really what we’re doing right now. We’re revisiting that…

MS. TIPPETT: You mean as a culture?

MR. JOHNSON: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. JOHNSON: …is because, certainly in the United States, the attitudes of individualism and of consumerism has generated a sense of Christianity as a club that we can belong to on our own terms. It is a consumer mentality, you know, the Jesus who fits me, the Jesus who speaks to me. And there’s this desire to locate somehow in history a precedent, a legitimation, an antecedent for that particular Jesus. We have lost in America, in particular, the sense of being church. That is, of being a public institutional body that has a creed, that stands for something, that has a specific identity, which requires something of its members, which holds its members to certain kinds of commitments. That’s precisely the issue.

MS. TIPPETT: And so what would you say to someone who, through the historical Jesus debate of recent years, through The Da Vinci Code, through the writing of Elaine Pagels, through a lot of the popularized books about Jesus or about the church of the New Testament, said that their idea of Christianity has opened up and become larger and more generous, and that what you seem to be forcing on them, wanting them to take, is a narrow view of Christianity which was decided upon…

MR. JOHNSON: Eighteen hundred years ago or whatever it is, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …1800 years ago. That that’s what you’re asking them to do, and that that doesn’t make any sense either.

MR. JOHNSON: It’s a very difficult question because, again, it goes right exactly back to the premises I just mentioned. Is Christianity the disclosure of a truth about God and a truth about the world which has a character which is not that simply of individual choice — Jesus is of a certain character, as disclosed in the four canonical Gospels; that is, he is a person of radical obedience to God and of radical self-disposition to others? That’s not a narrow view of humanity. It’s a definite view of the world, but it’s not a narrow view of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: So, OK, let me just ask the question in a different way. For you, as someone who has spent his life, not just as a person of faith but as a scholar steeped in these texts, I mean, is it your understanding and experience that everything that you need to live with about the nature of God in terms of scripture in our time is contained in those texts, in that body of writings, which was closed in the third and fourth centuries?

MR. JOHNSON: Oh, of course. I mean, and the silly thing about this is the implication that the canon is a very narrow and circumscribed and rigidly uniform. It is, in fact, astonishingly diverse.

MS. TIPPETT: OK, say more about that, about how you experience that diversity.

MR. JOHNSON: Well, I mean, you have just a variety of literary genres, a variety — I mean, the four portraits of Jesus in the four Gospels are marvelously flexible and marvelously vivid and quite distinct. What emerges as the same in those four portraits is a narrative rendering of a certain character, which is clearly identifiable and very, very challenging and prophetic. This notion of living a life in utter obedience to God and in radical love for one’s fellow humans is extraordinarily powerful, and yet it is rendered literarily in four diverse ways. You simply cannot collapse the four Gospel narratives into a single, homogeneous story. That’s what Tatian tried to do. That’s what the church rejected.

MS. TIPPETT: New Testament scholar Luke Timothy Johnson.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today we’re exploring the early centuries of Christianity in light of The Da Vinci Code. The original novel landed on book shelves with other popular works about writings that didn’t make it into the New Testament. One reason for this surge of new information about the biblical past is the success of archaeology in the last century. For example, in 1945, peasants digging near the Egyptian village of Nag Hammadi discovered a jar buried there since the fourth century. Inside it were full and partial texts of 52 documents. Among them, a large number of Gnostic scriptures.

The Gospel of Thomas was perhaps the most spectacular find of Nag Hammadi. Through other ancient sources, scholars knew that this had been an important Gnostic Christian text. Now they could read it in full for the first time, and so can we. It is a collection of 114 secret sayings of Jesus written somewhere between 50 and 140 of the Common Era. Parts of Thomas are similar or identical with sayings in the canonical Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. But others portray a very different Jesus, more mystical perhaps and, in places, utterly inscrutable. Here’s how the Gospel of Thomas begins:

READER: These are the secret sayings which the living Jesus spoke and which Didymus Judas Thomas wrote down. And he said, “Whoever finds the interpretation of these sayings will not experience death.” Jesus said, “Let him who seeks continue seeking until he finds. When he finds, he will become troubled. When he becomes troubled, he will be astonished and he will rule over the all.”

MS. TIPPETT: The Gospel of Thomas does include meditative sayings that appeal to modern readers. Like other Gnostic texts, the Gospel of Thomas also takes a dualistic view of human and divine nature. The flesh is suspect and corrupt, and only the spirit is desirable and pure. Here’s one of the controversial passages from the end of the Gospel of Thomas, which readers have interpreted in many different ways:

READER: Simon Peter said to them, “Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of life.” Jesus said, “I myself shall lead her in order to make her male so that she too may become a living spirit, resembling you males. For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven.”

MS. TIPPETT: I asked Luke Timothy Johnson why, in his understanding, a text like the Gospel of Thomas did not receive a place in the New Testament canon.

MR. JOHNSON: What is good in the Gospel of Thomas is also found in the canonical Gospels. I mean, one of the reasons why I follow those scholars who date Thomas rather than early — rather later is that it seems to me to be working with the canonical Gospels in adding in new materials in order to create something distinct. The Gospel of Thomas is not necessarily — it has some striking statements, right, it has some lovely, striking words that are found there which have a certain mystical bent. But if you take the materials in the Gospel of Thomas that are not drawn from the canonical Gospels and simply lump them together, what you find is cultivating a spirit of radical dualism, of, you know, “He who has found the world has found a corpse.” It is not necessarily good news for women. And this is another sort of weird sense that somehow Gnostic texts are better for women than the New Testament texts.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, there are those very strange lines at the end of Thomas.

MR. JOHNSON: Yeah, that Mary must become a male…

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. JOHNSON: …before, you know, and you’ve got the male principle. And look, the New Testament texts with regard to women are clearly androcentric, patriarchal, one could even argue, sexist. But it’s a functional sexism. That is, women shut up because that’s the custom, or that’s the way it’s supposed to be. One can negotiate that in light of feminist commitments. But in Gnostic texts, Sophia, the feminine principle, if you will, is the source of error. Well, this cannot be negotiated because it’s ontological not functional.

MS. TIPPETT: What did the church lose and what did the church gain from creating a canon, from closing the canon?

MR. JOHNSON: One of the things that it gained, I think, is the possibility of an open history of interpretation.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you write that, but what do you mean? I’m not sure I quite understand what you mean when you say that.

MR. JOHNSON: Texts and interpretations, not everything can be variable. Something has to stand still. If feminists, for example, want to have an open canon, as some of them argue, then they have to have a closed system of interpretation. So Rosemary Ruether says only those texts which lead to the liberation of women are to be regarded as authoritative. In other words, something has to be constant. You can’t have an open canon and read texts as authoritative which lead to the oppression of women. Correct?

My argument is that when you have a collection of texts as various as the 27 writings of the New Testament are, plus, by the way, all of the writings of the Old Testament, which Christians also read, what that enables is a historical conversation across centuries, which is at once consistent and yet always changing. Because if we believe the living God is at work in people’s lives, leading them into new understandings, into new insight, then these texts can be made theologically to yield new things. But this is only possible if that 12-inch ruler stays a 12-inch ruler.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, if everyone across time is conversing with the same material.

MR. JOHNSON: That’s right. And the function of tradition is not to live in the past, it’s to secure the future. And when we play with these basic instruments of self-definition, when we say, “Oh, let’s bring in these other texts, and we’ll read these in the assembly,” and so forth, or “Let’s take the Lord’s Prayer and call God mother, father,” and so forth, we know what we mean. Right? Because we grew up in the tradition. And it does us no harm, because we are actually troping a consistent, fixed tradition. But the next generation will not know what it means. And so what happens is that we cut off the conversation with us. We are the end of history.

MS. TIPPETT:New Testament theologian Luke Timothy Johnson. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, can fiction really pose a danger to thousands of years of tradition? Also, Bernadette Brooten on real discoveries about women in the New Testament and the truth about Mary Magdalene.

Continue this exploration at speakingoffaith.org. This week learn more about the nature of Gnosticism and other early movements and find links to noncanonical writings which you can read in full for yourself. Use the Particulars section on our Web site as a guide to this program. Download an MP3 to your desktop, or subscribe to our free weekly podcast. Listen at any time, at any place. Also, sign up for our free e-mail newsletter. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Deciphering The Da Vinci Code.”

We’re exploring what really happened in the early centuries of Christianity. My guest, Luke Timothy Johnson, criticizes what he calls the mischievous effect of The Da Vinci Code and other works like it. He says they impart a mix of fact and fiction about Christian history without a framework of knowledge to put them into perspective. Yet some of the factual revelations in The Da Vinci Code do contradict what many people learned in Sunday school.

The Bible does not say that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus, but neither is she ever actually described as a prostitute. So I asked Luke Timothy Johnson why misconceptions like this have rarely been publicly corrected by clergy and scholars. He had a passionate response to that question, critical at once of the limits of churches and of scholarship. Sacred writings became sacred, he insists, not by being read but by being lived. And Luke Timothy Johnson says his own sense of this comes, in part, from several years he spent as a Benedictine monk.

MR. JOHNSON: And as a monk, we sang the psalms and read scripture out loud, five hours a day. So when I went to Yale to get a Ph.D. in New Testament, I was stunned by sort of the academization of all of this and especially by the privileging of history as somehow, if we could get the history right, then, you know, everything would be OK. We have to find the historical antecedent. And that was quite a contrast from living within, in fact, a living tradition in which scripture was almost kinetically inhabited. I mean, you bowed and scraped and genuflected and sang scripture. So the notion of scripture as being a cadaver that one performs an autopsy on, as opposed to a living body with which one danced, was stunning to me, and I never have completely bought it. And I think that part of my peculiar position within scholarship is that I actually am not only postmodern but premodern. I have never bought the premise of modernity that history is the only way of knowing.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, but what you’re describing to me also is what you see as the culture in which this canon was created. Right? You said these were…

MS. TIPPETT: …texts that people read aloud and lived with in community, and that’s how they made their selection process.

MR. JOHNSON: That’s right. And that’s why — I mean, we go back to our first point, in that the real crisis that we’re facing culturally is the almost complete collapse of that sense of community, where people learn about their Bible not liturgically, not in practice, but as an educational process in Sunday school or at Barnes & Noble.

MS. TIPPETT: So you’re saying that even if Sunday school did a better job of teaching people what’s in there and what’s not in there and whether Mary Magdalene was really a prostitute, you’re saying that that wouldn’t even do it?

MR. JOHNSON: Right. It’s too much of a head trip. I mean, you know, religious texts — I mean, you know, Native American text, Buddhist text, none of it is terribly logical and self-consistent. They work existentially. They work in prayer. They work in practice. They get resolved in the rhythm of life, not through segmenting of sources. So partly what has happened is this sort of academic captivity of the church, the weird circle in which academics train seminary professors who train pastors who then, you know, are in that same circle in which the historical and the critical is privileged over the existential and the organic. This weird kind of situation simply now has spun outside the control of the academics and of the church because of the proliferation of media and, you know, the astonishing capacity of books and publications and the National Examiner to get to everybody in a kind of freelance manner.

MS. TIPPETT: So you’re saying that now what feels like liberating new information, which is coming by way of novels and popular academic books and TV documentaries, in fact is an extension of the same problem. It’s not enlightenment. It represents in itself a narrow way for this kind of religious information to be communicated.

MR. JOHNSON: That’s right. And, in fact, part of the problem is that information is transformation.

MS. TIPPETT: But we have this idea, you mean, in our time, that information is transformation.

MR. JOHNSON: Yeah, and it’s not. Information is information. I must say, I’ve read all of these writings, of course.

MS. TIPPETT: The noncanonical texts.

MR. JOHNSON: The noncanonical texts, and especially the Gnostic writings. And, as I said, with some exceptions, the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Truth, parts of the Gospel of Philip, there are some really stunning and quite beautiful writings in the Nag Hammadi collection. But much of it is also gobbledygook, almost nonsense syllables. And I don’t see anything there, with the exceptions that I noted, that represents some kind of liberating impulse for contemporary Christianity, a way forward. Quite the opposite. I think it tends toward a kind of hyper-individualism which we already have too much of.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, it’s interesting, some say that part of the appeal of these new writings and new theories about non-canonical texts, about the figure of Mary Magdalene is because modern American Christians want to pick and choose what scriptures work for them.

MR. JOHNSON: That’s exactly right. I mean, the notion of a canon within the canon or an expanded canon is — we go back to that same issue, is Christianity something that we make up and, therefore, we pick the collection that we want to read? Or is it something that we have received? Is it a gift that has been given to us that we are asked to nurture, to make grow, to live within? And part of my difficulty as somebody who would like to think of himself as actually rather liberal within the spectrum of Christianity today is that it’s extraordinarily difficult, it seems to me, to occupy a place of critical loyalty, you know, within this, and that we really are in real danger of simply letting go the fabric of the tradition in such fashion that we may not be able to knit it back up again.

MS. TIPPETT: Luke Timothy Johnson is R.W. Woodruff Professor New Testament and Christian Origins at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University. His books include The Writings of the New Testament. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faithfrom American Public Media. Today, “Deciphering The Da Vinci Code.”

The real, behind-the-scenes star of The Da Vinci Code is Mary Magdalene. The story suggests that her prominence in Jesus’ life was covered up as Christianity suppressed the early influence of the sacred feminine. In this, the author, Dan Brown, freely mingles pagan goddess mythology with church history. But recent scholarship has yielded a different picture of the role of women, both in the circles around Jesus in his lifetime and in the earliest decades of Christian history. Bernadette Brooten of Brandeis University has been a leading figure in articulating these new findings. She won a MacArthur “genius” grant for her discovery of a genuine biblical cover-up. An apostle named in one of Paul’s letters in the New Testament was not a man, as many generations of translators had falsely indicated, but a woman. I asked Bernadette Brooten to take me inside new knowledge about women, the Bible and the early church and how this might inform modern people intrigued by The Da Vinci Code.

PROFESSOR BERNADETTE BROOTEN: What we had learned, what people, what the general public and scholarship thought that we knew in 1970 was that there were women in the early church. They were not very important. If they were subordinate, they were relatively satisfied with that state of affairs because they didn’t know any better, because, in that time, people didn’t have any other image of what life could be like.

MS. TIPPETT: And how have you come to imagine that differently?

MS. BROOTEN: Well, it started for me with discovering that there was a female apostle mentioned in the New Testament by the name of Junia. And that was in Paul’s Letter to the Romans, chapter 16, verse 7. And what I learned was that the Greek could be interpreted in more than one way and that scholars had interpreted the name in the early church as a feminine name, but that, in the Middle Ages and then especially in the Reformation, that scholars, especially as they were translating the Bible into modern languages so that the Bible was becoming more accessible to the common people and therefore would have more of an impact on the common people, scholars then began to be hesitant about translating the name as a female name because they said, “If this is a female name, then this was a woman apostle. There cannot have been a woman apostle, therefore, this must have been a male name.”

MS. TIPPETT: And then, my understanding is, that you ascertained that and that your discovery then was integrated into the new revised standard version of the Bible.

MS. BROOTEN: Yes, that’s right. That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: So I have my revised standard version, which was a previous translation. And, I mean, just looking at that chapter 16 of Romans, you know, it’s a fascinating list, even not knowing the language. I mean, the first person Paul commends there is “our sister Phoebe, a deaconess of the church.”

MS. BROOTEN: Yes. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And there are, I think, as many as 20 or 30 names in there, and many of them are impossible for an English speaker to tell the gender of. But some of them are clearly women. And then you found that the person who here is identifying as Junias and called in this English translation, “my kinsman, a man of note,” right…

MS. BROOTEN: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: …in fact, also was a woman, which makes you wonder how many of these names are women.

MS. BROOTEN: About a third of them are women.

MS. TIPPETT: A third of them?

MS. BROOTEN: Yes, just about a third of them are women.

MS. TIPPETT: And then the issue is not what the early church did to women, but how later generations became blind to those women.

MS. BROOTEN: Yes, that’s right. That’s right. Because there was a period in the early church for some centuries in which women still had a knowledge of these early Christian women, in which they were important to them and in which women had titles of leadership in some congregations, titles such as elder that is the word “presbyter,” that is the word that also our word “priest” derives from. So there were women who were active as religious cultic leaders in some Christian congregations. And there were women in the Jewish synagogue who had similar titles of leadership. So that also is something that wasn’t known. We also have learned that there were women who were active as cultic functionaries in other religions, in pagan religions in the period. So we now have a much more differentiated picture of the situation. It was not just bleak for women with respect to women’s leadership, but, in the course of time as the church became more bureaucratized, then those women tended to be pushed to the margins and the memory was lost.

MS. TIPPETT: And I think when you have the luxury of getting a theological education, of learning to get inside the New Testament, what you learn to become attentive to, let’s say, just in the writings of the apostle Paul, is a real struggle going on inside him and that he’s addressing that issue in many different ways. What I think I get frustrated by is I don’t think everyone should have to go to seminary to be able to be attentive to these things, which is why I suppose these kinds of conversations are important.

MS. BROOTEN: Yes. Yes. Well, you know, we need a stronger tradition of being able to work with ambiguity.

MS. TIPPETT: Even in the Bible.

MS. BROOTEN: Even in the Bible. That’s right. As you say, with struggle and tensions within a text, because the way that Christians have typically worked with the Bible, in recent years at least, has been to try to find the biblical teaching and then to neglect other aspects of the biblical teaching. So there are clear statements in the New Testament that wives should be subordinate to their husbands, that slaves should obey their masters in everything, that women should not speak in church, that a woman should not teach or have authority over a man. Those teachings are all there. And then there are other hints that that wasn’t the full story, that not all women were following these teachings.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m curious about how you think about — let’s see, Newsweek called Mary Magdalene this year’s “it” girl.

MS. BROOTEN: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: “It” girl. All right. Now, it is true that all four Gospels transmitted her name, which is unusual.

MS. BROOTEN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And also true that she is not said to be a prostitute in the Bible, even though that’s something that got stuck in our — the collective minds of the church and Christians. Tell me how you think about what you know from your scholarship about where Mary Magdalene fit in and what happened to her, the memory of her.

MS. BROOTEN: Yes. Yes. Well, we know that she was a close follower of Jesus. She was at His crucifixion, so she was one of the few disciples who stayed while He was being crucified, that she and other women supported Him from her funds, that she had been the recipient of an exorcism.

MS. TIPPETT: And that’s where that prostitution idea probably originated?

MS. BROOTEN: Well, yes, that and then the false identification of her with the woman who was called a sinner in the city, who was known as a sinner in the city. And then also the fact that in the Gospel of John, Mary of Bethany was said to have anointed Jesus’ feet. But Mary, Miriam in Hebrew, was the most common name for women among Jewish women in the land of Israel in this period. So, in the one sense, it’s somewhat understandable because Mary was a common name and the early church would conflate people of the same name. But in another sense, the knowledge of Mary Magdalene as a leading disciple is something that was lost to the later church.

MS. TIPPETT:Scholar of early Christian writings Bernadette Brooten. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Deciphering The Da Vinci Code.”

There is a Gospel believed to have been written in the second century and attributed to the memories of Mary Magdalene. It suggests that Mary Magdalene was so close to Jesus that rivalry arose among the other disciples.

READER: When Mary had said this, she fell silent, since it was to this point that the Savior had spoken with her. But Andrew answered and said to the brethren, “Say what you wish to say about what she has said. I, at least, do not believe that the Savior said this. For certainly these teachings are strange ideas.” Peter answered and spoke concerning these same things. He questioned them about the Savior. “Did He really speak with a woman without our knowledge and not openly? Are we to turn about and all listen to her? Did He prefer her to us?” Then Mary wept and said to Peter, “My brother Peter, what do you think? Do you think that I thought this up by myself in my heart or that I am lying about the Savior?” Levi answered and said to Peter, “Peter, you have always been hot tempered. Now I see you contending against the woman like the adversaries. But if the Savior made her worthy, who are you indeed to reject her? Surely the Savior knows her very well. This is why He loved her more than us.”

MS. TIPPETT: From a second-century, noncanonical Gospel of Mary Magdalene.

Although this text only survives in fragments, one recent book reimagines it as a whole. The best-selling novel The Da Vinci Code speculates that Mary Magdalene was Jesus’ wife and that she is the figure reclining next to Him in Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of The Last Supper. After The Da Vinci Code hit best-seller lists, one national magazine dubbed Mary Magdalene “the star of a mega best seller, a hot topic on campuses, and rumored to be the special friend of a famous and powerful man.” Bernadette Brooten says that, as Christianity became the imperial church, it did suppress its early practice of female leadership. But virtually all experts agree there is no evidence that Mary Magdalene was romantically linked with Jesus. In fact, this kind of speculation degrades the more substantive picture of Mary that serious scholarship is uncovering.

MS. BROOTEN: The idea that Mary Magdalene was married to Jesus, it’s a very big leap. And furthermore, I see it more in line with the question of the, especially Catholic, taboo on sexuality and on the sexuality of Jesus. You know, we had something similar with The Last Temptation of Christ. And I have to say that seeing Mary Magdalene as in a romantic relationship with Jesus seems to me more in line with the idea that Mary Magdalene was a former prostitute than that she was a leading disciple of Jesus. Because looking at Christian art through the centuries, we find Mary Magdalene depicted usually voluptuously, a beautiful woman, what with her alabaster jar and frequently with sexual overtones in the way that she’s responding to Jesus or in the way that Jesus is responding to her. So I’m suspicious of that aspect of it.

MS. TIPPETT: It does emphasize her, again, even if in a different way, as primarily a sexual being, doesn’t it?

MS. BROOTEN: Right. That is that apparently in the popular imagination, it’s difficult to envision Mary as a serious person who was taken by the theological message of Jesus and decided to shape her life around it, which is the evidence that we have from the New Testament and from beyond the New Testament.

MS. TIPPETT: Part of the larger picture of the discussion that’s arisen out of The Da Vinci Code, the focus on Mary Magdalene, has been also regular people suddenly becoming aware that there is this body of noncanonical literature, these writings that did not make it into the Bible but which were very important. Some of them more important than others to early Christians. How do you use those kinds of texts? How do you think about how they might be valuable or how their value is limited for modern people suddenly becoming aware of them?

MS. BROOTEN: Again, for me, the matter is not discovering sources outside of the New Testament that then are ideal sources or kind of a new canon, but that give us a broader picture. We’re not going to find, you know, the Holy Grail that will do it all. Rather, what we find is more texts about the ways in which people have struggled with what it means to be human and to have some ultimate belief. And that, to me, is what is inspiring and helpful. And I believe that by taking the freedom to study and ultimately to disagree with portions of the New Testament or of writings outside of the New Testament that I’m then taking the authors very seriously, because I’m allowing them potentially to persuade me by not assuming from the beginning that they must persuade me.

MS. TIPPETT: Bernadette Brooten is Kraft-Hiatt Professor of Christian Studies and director of the Feminist Sexual Ethics Project at Brandeis University.

Earlier in this hour, you heard Luke Timothy Johnson of Emory University.

If you’re interested in the history and writings studied by my guests today, don’t limit yourself to movies or popular works. Read the original texts for yourself. At speakingoffaith.org, discover links to non-canonical scriptures and other ancient documents including the Gospels referenced here and in The Da Vinci Code movie. These texts are fascinating to read, and, in some ways, they are themselves an antidote to conspiracy theories. At speakingoffaith.org this week, you’ll also find a Web-only conversation I had with Bart Ehrman. He’s written appreciatively about varieties of faith Christianity left behind. The readings on today’s program were taken from his book: Lost Scriptures: Books That Did Not Make It Into the New Testament.

Continue this conversation at speakingoffaith.org. Contact us with your thoughts. Listen on demand for no charge to this and previous programs in our Archive section or subscribe to our free weekly podcast. You can also sign up for our e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each topic and a preview of upcoming shows. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

This program was produced by Kate Moos, Mitch Hanley, Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson with editor Ken Hom. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss with assistance from Ilona Piotrowska. The executive producer of Speaking of Faith is Bill Buzenberg. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections