Peter Gomes, Jean Bethke Elshtain, and Chris Hedges

Religion in a Time of War

More than any crisis in modern memory, the War on Terror—including the current U.S. military presence in Iraq—is being debated in religious, usually Christian, terms. We explore the nuances of that debate with a former war correspondent, a political theorist, and a renowned preacher. We ask how and whether Christian principles really make a difference at this moment in our national life—and if not, why not?

Image by Kieran Cuddihy/Flickr, Attribution.

Guests

Peter J. Gomes was the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and minister to Memorial Church at Harvard University.

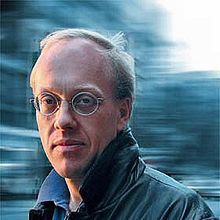

Chris Hedges is a writer for The New York Times, veteran war correspondent, and author of War is a Force that Gives us Meaning.

Jean Bethke Elshtain was an author and Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

Transcript

April 25, 2003

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. Today, Religion in a Time of War. Since 9/11, Americans have been focused on the interplay between religion and conflict in the Muslim world. The Christian images and vocabulary have been increasingly prominent in America’s public conversation, especially around military action in Iraq. From the first, the Bush administration employed Christian terms in its rationale for launching an attack. Yet, as the war on terrorism and in Iraq unfolded, religious arguments against military action have also grown vehement, strikingly so in comparison with the first Gulf War and even with Vietnam. Leaders of Christian and non-Christian traditions have come out in opposition to the use of military force. Yet popular poll results remain steady. A majority of Americans have condoned military action with support even higher among Christians who attend church once a week or more.

Today on Speaking of Faith, we’ll be in conversation with three individuals who bring unusual perspective to the role religion plays when America wages war. They’ll also reflect on how Christian thought could be deepening our national moral reflection. Jean Bethke Elshtain is a political theorist and one of the country’s leading thinkers on how terrorism is challenging just-war theory. Chris Hedges is a New York Times correspondent who studied theology before covering wars across the globe for two decades. But first, Peter Gomes, professor of Christian morals at Harvard and minister of Harvard’s Memorial Church, the first African-American to hold that office. He is a Baptist and a Republican and one of America’s greatest preachers. He preached at the first President Bush’s inauguration service. Yet in recent months, Peter Gomes began to write and preach vigorously against US military action, and his comments have been widely reported here and abroad. I asked Reverend Gomes about his sense of what Christian tradition has to say on war and how Christian language is being used in our public life at this moment.

PETER GOMES: Well, it’s a bewildering point of view for any person who speaks for or out of a religious tradition. As a Christian, while I am not a strict pacifist and most Christians are not, all of us as Christians are under a severe injunction to be very suspicious of war or violence as a solution to anything. It is all too easy to assign our religious scruples and principles to our political position and then bless whatever it is we want to do by the convictions of our own religion. That’s a peculiarly dangerous American practice. In the Civil War, for example, the South always claimed that God was on their side, and the North was certain God was on their side, and I remember Abraham Lincoln’s great line was, `We should pray that we are on God’s side.’ That’s a very different point of view.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve just published a new book called The Good Life: Truths that Last in Times of Need. I believe you’re out presenting your book and speaking about it. I mean, what are people saying to you about truths that last in times of need, you know, at this moment in our public life?

REV. GOMES: Well, I’ll tell you people are perplexed, people are puzzled and people do not like to have to make the choice between what their faith tells them on the one hand and what their country requires of them on the other. We’ve been pretty good in this country at compartmentalizing. You know, we know that Jesus preaches love and forgiveness and love your enemies and do not return violence for violence, and all of those things. And on the other hand, we are very prepared to take any means necessary to achieve whatever it is we feel we want in the world. And there seems to be no fundamental disconnect between those two. I’m finding as I talk to people that they’re aware of this disconnect and they feel uncomfortable about it. They feel pushed and stressed and strained. I mean, you have the extremes at either end. You have the America Firsters, who will bomb anybody for any purpose. And you have the absolute pacifists who will do absolutely nothing. But most of us find ourselves in the middle, somewhere having to contend with good wars and bad wars, with a clear Christian conscience and an ambiguous Christian conscience.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

REV. GOMES: And that’s where I think most of the people that I see are. And when pressed between the president of the United States and the weight of the present government, and their Sunday pastor and an hour’s worth of Christian teaching, most of them under fear and anxiety or just general habits will conform to what the culture requires, not what the faith requires.

MS. TIPPETT: And do you think that’s a particularly American characteristic?

REV. GOMES: Oh, I do, because I think there’s no other country on Earth which makes more of a public fetish, if you will, of religion’s connectedness to our national destiny and our political process. So if somebody didn’t know any better, they would assume that all that we do is derived from how we understand our faith to require us to behave. But if you’re a Christian, that’s a very complicated and serious problem. The pope and the bishops of the Roman Catholic Church have without hesitation ruled this war as unacceptable, and so have nearly every other major Protestant denomination with the possible exception, indeed, of the Southern Baptists and certain independent fundamentalist churches. But by and large, the American religious community officially has spoken and not very many people are particularly prepared to follow what they have to say.

MS. TIPPETT: I’d be curious about how you personally, as a person who’s spent a lot of time with his Bible — how you are thinking through America and the war on terror and the situation in Iraq.

REV. GOMES: One of the things that the Bible points out over and over again in both the Hebrew Scriptures and in the Christian Bible — the dangers of the arrogance of power. The great question is not should we have it or not. The great question and the biblical question is how do we use wisely and prudently, not just for ourselves but for the world, the power that we have. That seems to me both a biblical and a political question. Everything that we do has to be judged, it seems to me, in light of Jesus’ summary of the law: love of God, love of neighbor. Seems to me, you know, the moral mandate of the Christian faith is very clear. I look at the Lord’s Prayer, I look at the Beatitudes, and I look at the fact that in some real sense, the Christian witness is always to be against what appears to be the prevailing order. It doesn’t confirm the prevailing order. It acts as a countermeasure to it.

MS. TIPPETT: At every time…

REV. GOMES: Not every time.

MS. TIPPETT: …in every society?

REV. GOMES: But by and large, that is its mission because it’s not of this world. So while I have always seen the role of the state to provide a stable order within which religion can foster — that’s the genius of the American system — I’ve always seen the purpose of religion not simply to reinforce the values of the state but to transcend those values. And as a Christian, that has to be my first loyalty.

MS. TIPPETT: Harvard minister and professor Peter Gomes. When it comes to the morality of war, Christians have traditionally split over two strands of thought in the New Testament. One cites the Apostle Paul with his seminal passage in the 13th Chapter of Romans commanding early Christians to subject themselves to governing authorities, even the Roman Empire that ultimately persecuted them. But then there is Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, which teaches strict non-violence and is the source of the lyrical Beatitudes: Blessed are the poor in spirit, those who mourn, the meek, and also blessed are the peacemakers. I asked Peter Gomes how he would respond to the argument that the New Testament and especially the Sermon on the Mount represents an ethical ideal that simply can’t encompass the realities of modern geopolitics.

REV. GOMES: I follow the advice of G.K. Chesterton, who once said that the Christian faith has not been tried and found wanting; it has been wanted but never tried. And I think that’s a pretty profound observation at this point. And quite frankly, I think what would give me more satisfaction — if people said, `We’re not trying to be Christian about this; we’re being realistic politicians and this is how our policy is derived,’ that I can accept. What I find hard to do is to say, `Well, we must be realistic Christians, and there are certain parts of the Gospel that simply don’t work in this world, but let’s apply the patina of the Christian faith to our policy and call the whole thing Christian.’ That, I think, is both theologically and intellectually dishonest.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I have to say that in a country in which still something like 85 percent of the citizens will say that they are at least nominally Christian. As you say, there is such a wide spectrum of teaching within the Bible — it surprises me that there’s still not more soul searching…

REV. GOMES: Well…

MS. TIPPETT: …more struggle.

REV. GOMES: …quite right. It saddens me, but in part we’ve bought what I will call a cheap gospel and what Bonhoeffer called cheap grace. We like the benefits of what we understand the Christian faith to provide us — a sense of chosenness and being elect — and we love to say, `God bless America.’ We say it all the time. We don’t seem to understand that God doesn’t just bless things because he’s in the business of blessing things. God blesses things insofar as they meet with God’s approval and they are consistent with God’s teaching and they are consistent with what God expects of those who are his followers and believers. We want the blessing; we don’t want the struggle to figure out what it requires to get it. And that is largely because I think we are culturally and theologically a rather lazy people. We don’t like complexity and we don’t like to struggle.

MS. TIPPETT: In a sermon that you gave that’s been I think pretty widely reprinted, you talked about speaking in a large suburban Presbyterian church…

REV. GOMES: Yes, in St. Louis.

MS. TIPPETT: …yeah, and you said that these people love their country, they love their God and they asked this question — or this question was on their hearts: What do you do when your country is headed where you think your faith and your God don’t want you to go? How are you answering that question for yourself?

REV. GOMES: Well, the hope that I see is that more people than I might have expected are actually asking that question and are actually wrestling with it. And it’s not that I believe there is one clear, absolute answer. It’s not that I’m asking everybody to agree with me that this is the wrong war in the wrong time for the wrong reasons. I’m asking people actually to have to wrestle through the questions to come to whatever conclusion they can, which requires that they take their faith seriously and not just as a cosmetic for policy or custom. And so if you ask where do I see hope in a dark time, I see hope in the fact that these are increasingly legitimate questions. And it’s frustrating that the large swathe of Christians who are bold in these matters and the large number of denominations that have spoken on these matters are ignored. But the other side of that is, one of the important things that the New Testament teaches is that you cannot expect to prevail in a world that is not ordered along Christian principles. You’re always going to be struggling against the secular tide. And I think that’s also important for us to understand.

MS. TIPPETT: St. Francis of Assisi said preach the Gospel constantly and use words sometimes.

REV. GOMES: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder how you think about how this struggle — at least posing the questions of faith to a time of war — how this might manifest itself beyond what’s being said in pulpits, other places that observers might be looking for this to turn up.

REV. GOMES: Well, that’s hard to say. I mean, you’ve asked me to speak as a preacher and somebody responsible for a pulpit…

MS. TIPPETT: You’re right.

REV. GOMES: …where words are important and that’s what we do. But you know, the Gospel is only described in the pulpit. It is lived out in community. And how you, for example, carry on conversations about values, patriotism, love of God, love of country with young people, for example, with children is very important. So I think we’ve evolving, we’re moving from just the Sunday discourse nowadays of, you know, 20 filtered minutes usually on next to nothing of any great importance into an attempt to find out how can we discuss some of these most critical and important things in the world. Our job in the pulpit, I think, is perhaps to help form those questions and help provoke those questions, but the real discourse takes place long after people have left church.

MS. TIPPETT: Peter Gomes is Plummer Professor of Christian morals and Pusey minister of the Memorial Church at Harvard University. His books include The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Heart and Mind, and The Good Life: Truths that Last in Times of Need.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. Today, “Religion in a Time of War.”

JEAN BETHKE ELSHTAIN: Human beings are vulnerable creatures, we’re soft-shelled creatures. We huddle together for safety; we always have, we always will. And after a while, we learned how to form societies and to give them some lasting existence and how to do all the extraordinary things that human beings are capable of but that require a level of safety and security and civic peace to accomplish. That’s something that Americans really haven’t had to think about for a long time.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s Jean Bethke Elshtain, a renowned political theorist and an expert on just-war theory. Just-war theory, which insists that ethical standards can and should be applied to the activity of war, had its origins in early Catholic thought. In the 20th century, it was absorbed into the Geneva Convention and other international treaties. This quasi-religious approach to war stresses the Christian virtue of justice and posits that in pursuit of justice war is sometimes a legitimate recourse in political life. The theory lays out a number of criteria for both the ends and the means of war. Jean Bethke Elshtain has advised policy-makers and military leaders about how just-war theory in our time must adapt to the realities of terrorism. Some observers charge that the use of pre-emptive force in Iraq broached inviolable just-war principles such as the notion that wars should always come in response to an imminent threat and be a measure of last resort. But Jean Bethke Elshtain defends military action in Iraq in just-war terms and also in terms of Christian theology.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Just-war thinkers have for generations talked about the question of imminent threat of harm, where the actual harm hasn’t yet occurred, but the probability to a degree of nigh certainty that harm will come unless action is taken is something that has long been recognized in the just-war tradition. So it’s not something that’s brand-new. That said, it seems to me that if you go through the criteria of is there a justifiable cause, have other possibilities been tried and found wanting, is there a legal authority, is there a strong probability of success that you can really make a very strong case for just cause where Iraq is concerned. I think the challenge is going to come on the two central issues of the so-called in bello proportion or aspect of the just-war tradition, namely distinguishing combatants from non-combatants and then the whole issue of proportionality, that you use the force that’s needed in order to try to actually just bring the thing to a conclusion as quickly as possible while doing the least harm to non-combatants.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I read the statement that you made together with some other important thinkers…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …in November 2002…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …”Pre-emption, Iraq, and Just-war Statement of Principles”…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …and I’m wondering if just-war also places a sort of moral imperative on a leader like us; I mean, if there’s some — it’s not just good enough to do even what we think is just but that we have to think about our leadership and the moral standard that we’re setting.

DR. ELSHTAIN: You know, that isn’t per se part of just-war theory, but I think here the question is are there particular responsibilities that come your way given your enormous power, hence, your ability to do things that other states cannot, and given the fact that the United States is a polity that was founded in the first instance on the same sorts of universal principles that serve as the foundation for the just-war tradition. Now I think that there is a way to strengthen the universal nature of the argument having to do with intervention by the United States, and that is to argue that all human beings are of equal moral worth, so that when we look back at inaction in Bosnia and the fact that when UN peacekeepers, not called soldiers, UN peacekeepers are finally on the ground, under the rules of engagement, they stood by as, before their eyes, Bosnian Muslim boys and men were being beaten and seized and hauled off never to be seen again. And it just strikes me if you’re going to talk about a world of universal moral principles, that that kind of disproportionate valuing of human life becomes evermore problematic. And that I take to be consistent with the Christian origins of the just-war tradition…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. ELSHTAIN: …where all are equally children of God, all therefore beings of great dignity that is not given to them by their states, but is their gift as a child of God. And that has to be taken very, very seriously in all of these matters and may impose some very particular responsibilities on the United States given its own profession of universal principles and given its power.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, even given the fact that Christianity is being invoked strongly as part of our motivation for going — I mean, part of the reason this is a just cause. I…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Well, in fact, that’s very consistent with very strong arguments that St. Thomas Acquinas makes in his magnificent and unparalleled multivolume Summa where he argues that a requirement of caritas, of neighbor love, in the Christian tradition can, in fact, be and may well be the pre-eminent justification for the use of force, to respond to the claims of one’s neighbor in a concrete way that may involve risk to yourself. And he’s very, very clear on this.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, we’ll return with more of my conversation with Jean Bethke Elshtain, one of America’s leading thinkers on how just-war theory is adapting to terrorism. Also, New York Times correspondent and divinity school graduate Chris Hedges, author of War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning. Stay with us.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith. Today, “Religion in a Time of War.” I’m in conversation with political theorist and just-war expert Jean Bethke Elshtain, a well-known commentator on the intersection of religion and American public life. Her ideas are formed by her study of great Christian thinkers across the ages, from the fifth century church father and the source of just-war theory, St. Augustine, to the 20th century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Niebuhr’s name came up with remarkable consistency as I spoke with people on every side of our current conflict. He was a public theologian and a defining voice in convincing American Christians to support military force against the Nazis. Niebuhr is called a Christian realist, someone who charted a third way between the two New Testament poles of obedience to authority or strict non-violence. One of his most famous essays had this title: Why the Christian Church is Not Pacifist. And Jean Bethke Elshtain can be called a Niebuhrian thinker for our time. So I asked her the same question I had asked Peter Gomes ‘How does she make sense of the gulf between what America is doing in Iraq and what Christian leaders are saying about it?’

DR. ELSHTAIN: The way I’ve tried to understand it is that the jolt of 9/11 jolted people in different directions, and I’m thrown back then on the just-war tradition and on such great 20th century theologians as Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr…

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

DR. ELSHTAIN: …who confronted the threat of Naziism, and in the case of Niebuhr had been a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, had been active in a peace movement and then he saw the church as simply not capable of dealing with the threat that Naziism represented, just not capable of thinking about it and continuing to talk about peace when there is no peace, as the prophet Jeremiah said. And I think something like that is going on now. In a human rights universe, as in a universe in which human rights is a — now the lingua franca of the world in which people talk about their grievances in that language, regimes like the Saddam Hussein regime become evermore anomalous, evermore difficult to justify. And I think that sets up a kind of dynamic or a kind of momentum that Christianity has contributed to through…

MS. TIPPETT: Well, this is…

DR. ELSHTAIN: …its emphasis on human dignity.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Christianity has contributed to…

DR. ELSHTAIN: To…

MS. TIPPETT: …a sensibility which rejects that kind of a state.

DR. ELSHTAIN: And a sensibility which rejects those kinds of regimes, but then that next step is OK. Then in a situation where a regime of that sort poses a threat of imminent harm, what is the responsibility of the world, of responsible states to deal with that threat? And I think that’s the step that for a variety of complicated reasons, including some theological ones, people in our church leadership roles do not want to take. And the theological reasons that occurred to me as someone who’s been struggling with this is that the Niebuhrian tradition of confronting political evil in a fallen world, in a world in which one has to anticipate and expect that bad things are going to happen unless something is done to stop them happening — I think that has simply been dropped. It has been lost.

MS. TIPPETT: I think he’s on everyone’s lips right now, though. It’s amazing to me.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Well, I think he’s on the lips of people who realize that churches have been falling short.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I was looking at Niebuhr the other day…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …and when he says something like this — that the New Testament does not envisage a simple triumph of good over evil…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: …in history, it sees human history…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: …involved in the contradictions of sin to the end.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Indeed. Indeed.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a complex view of reality, which Augustine…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Indeed.

MS. TIPPETT: …also had, didn’t he?

DR. ELSHTAIN: Indeed. There’s this sense of a long twilight struggle. A phrase from John F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech that much of the time, we are in a world where we’re struggling — I call it the fog of politics.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Clausewitz, the great theorist of war, talked about the fog of war. There’s a fog of politics where people are struggling to make judgments and the just-war tradition is about making judgments in a world where you’re always working with less than perfect knowledge, always struggling, knowing that the best that you can hope for is unlikely to be realized. You just want to try to stop the worst from happening. That’s — those are the tasks that some have shouldered, that our statesmen take up and take on. And it bothers me enormously that those of us who have — or many who have the luxury in a sense of living in a world that is in part made safe by those who shoulder that responsibility stand by and seem to be evoking a kind of moral purism — you know, `We’re not going to get our hands dirty,’ when, in fact, we assign certain people the task of getting their hands dirty.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. ELSHTAIN: `We want to be safe but please don’t tell me what you’ve got to do to — to make sure that that happens.’ And I think that’s irresponsible and I think it’s unfair.

MS. TIPPETT: This is a sentence from your manuscript of your new book…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes, ma’am.

MS. TIPPETT: …”Just War on Terror,” and this is you writing about Augustine, who…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes. Ms. Tippett: …is another one of these figures who wrestled with the complexity.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: You said, `Augustine believed that the only valid war was to restorepeace, that it must be the last resort and that it should always be regretted, not rejoiced after — over.’

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And I guess I’m also looking for that religious sensibility in our country right now, and not finding it and wondering it feels like people of faith take one side or the other. I don’t know, and maybe I’m just talking about the leadership and I’m not looking beyond that, but…

DR. ELSHTAIN: I know what you’re saying.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. ELSHTAIN: I mean, what is often wanting over the long course of American history actually is a sense of history’s tragedies and history’s sadness, its losses, the fact that there are very few unadulterated triumphs. That’s an attitude, an awareness of tragedy and of irony. Niebuhr talked about the irony of American history. That doesn’t sit very well with our sort of can-do optimism, that sort of mainline Protestant civil religion, if you will, that was ours for generations that did so much, I mean, contributed so enormously to the building of American civil society. But it really was wanting in that quality or that aspect because that sounds to us defeatist…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. ELSHTAIN: …or it sounds morbid, want — you know…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. ELSHTAIN: …why are you looking on the dark side of things?

MS. TIPPETT: Right, we’re so optimistic.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Right. That’s right. We’re so optimistic.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. ELSHTAIN: And I think we’re called instead theologically to be hopeful, which is not the same thing as being optimistic. To be hopeful is to live in anticipation of a possible good that might come and to work to try to achieve that good, knowing that that good will always be in the realm of something less than ultimate. The notion of a perfect peace or a perfect justice can aspire it, but if we try to achieve it in this world, we do a tremendous amount of damage because then our projects become triumphless, then they become too grand, and I think that notion of sadness, that — this sort of somber recognition about the solemnity of events — is something that Abraham Lincoln certainly had, but Abraham Lincoln is a very, very rare American political figure, and he believed that he was presiding over a just cause, and he authorized a policy of unconditional surrender. It’s that kind of recognition that I think we find it difficult to muster because it doesn’t have the sort of moral purism and certainty that unfortunately I believe some of the people now calling for peace evoke, and it doesn’t have the sort of `By gosh, we’re going to go in there and do the job.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. ELSHTAIN: This is going to involve a long commitment to a very damaged society, one that will need, if you will, care and tending in a non-patronizing way for a good long time to come. And that — that should be an occasion for some sober reflection, not an occasion for either triumphalism or a kind of removed moral purism.

MS. TIPPETT: As a person of faith, you know…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …what are your questions and concerns as we move into this, as you say, this long haul? What’s the religious deliberation that you would throw into the mix that’s out there?

DR. ELSHTAIN: Well, part of the religious deliberation that I would put into the mix is whether Christians are prepared to incur the kind of guilt before God that comes from acting in the world in certain very difficult and tragic circumstances. Are they prepared for that, to stand before God as someone who has incurred guilt that comes from a responsible action? Thinking about those issues is something that occurs to me rather frequently these days.

MS. TIPPETT: Jean Bethke Elshtain is Laura Spelman, Rockefeller professor of social and political ethics at the University of Chicago. Her new book is Just War Against Terror: The Burden of American Power in a Violent World. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith. Today, “Religion in a Time of War.”

Chris Hedges, my next guest, is a correspondent for The New York Times. He has covered most of the world’s major conflicts as a war correspondent for the past two decades. He was there when violence raged in places like El Salvador, the West Bank in Gaza, Kosovo and Iraq.

CHRIS HEDGES: I wanted to make sense of it and I wanted to do it as somebody who had seen it up close and not only witnessed it but suffered the contagion of war.

Prior to becoming a journalist, Hedges completed a Masters of Divinity at Harvard and worked in Boston’s public housing projects. And he has written a book, “War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning,” which is a journalistic memoir shaped by theological reflection. Though he takes a very different view of the current crisis, Chris Hedges, like Jean Bethke Elshtain, bemoans the absence of a nuanced religious voice like that of the late public theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. And his book, which I suspect Niebuhr would have appreciated, is an extended reflection on the moral complexity of war, rooted in personal experience. Hedges’ account of the Gulf War, for example, contains some of the most graphic description I have read of the cruelty of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Yet, war, Hedges reminds his readers again and again, is organized murder, necrophilia. Chris Hedges doesn’t believe that anyone is immune to being corrupted by involvement in war, including journalists. He confesses his own long addiction to a fascination which television sanitizes for the rest of us, yet still manages to convey: the intoxication of battle.

MR. HEDGES: And I woke up a few weeks after 9/11, I looked around New York and I thought we’d all become Serbs. And that was very much the idea behind the book to explain the poison that war is and how similar that poison is no matter where you’re from, that…

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean we all become the Serbs and what do you think when you say that?

MR. HEDGES: Well, in terms of the flag waving, the patriotism, the self-exultation, the denigration of our enemies that takes place in wartime, when suddenly people feel that they belong to the nation. You know, we used to call it in Bosnia the Linda Blair effect, where you think you’d found the one sane Serb and their head starts to spin around after 10 minutes. There is a kind of collective insanity.

MS. TIPPETT: I think another truth that you tell in this book that I have always felt was lacking a bit is, you know, the way in which we, and I think the media does this, people use religious language in conflicts and then it is called a religious conflict when, in fact, it’s really people with all kinds of agendas that have nothing to do with religion, just cloaking themselves in that. I don’t know if you could say that’s happening in this country, though.

MR. HEDGES: I think it is. You know, I think once political leaders claim to understand the will of God and to be able to act as the agent of God, they become dangerous. I think, in my mind, that that is a complete misuse of religion. However, having lived through many countries that have been in conflict, it’s a very effective use of religion. It sanctifies the cause. It promises that the divine is on our side, which is a kind of part of this self-exultation that always takes place at a time of heightened nationalism and blind patriotism. So to sanctify your cause and wrap yourself in a religious mantle is another effective way of justifying the atrocity that is war, the death of innocents, you know, of hiding that kind of horrible moral ambiguity that always takes place in wartime.

MS. TIPPETT: But I think it’s important to clarify that you say in your book,I mean, you accept force as a given, something that you think will always happen in human life and you give the example of Kosovo where you longed for armed intervention to end that conflict. So you’re not a pacifist.

MR. HEDGES: No.

MS. TIPPETT: You might be sounding like one.

MR. HEDGES: No, I’m not. And, I think war is unfortunately an inevitable part of the human condition. I believe that after the Holocaust, if we’ve learned anything from the Holocaust, when we have the capacity to stop genocide and we do not, as happened in Rwanda, we are culpable. But I also believe that no matter when you use force, even if it’s for a justifiable cause, it still corrupts, taints, distorts and deeply damages a nation, that those physical and psychic wounds are inevitable. And one doesn’t want to start messing around with the poison that is war, and that’s, of course, my problem with this war. It certainly does not fit into any just-war theory I have read.

MS. TIPPETT: You talk a lot about the moral universe, the moral universe of people you encountered in different conflicts. You know, OK, so all of this that you’re describing now in your frustration, you know, what is it doing to our moral universe? How would you like religious voices to be part of that deliberation? Are you hearing them be part of that deliberation at all?

MR. HEDGES: My problem with the religious community is that it often swings to the other extreme in the sense that it’s naive about how the world works.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. HEDGES: You know, I think religious people have to be a little more hard-headed with those that oppose the war about Iraq. I mean, the fact is he does have biological and chemical agents, as far as I can tell, and he probably is hiding them. We can’t be naive about the character of that regime. The problem for me with many sort of liberal religious leaders is that they have a hard time accepting human nature as it is and they try and mold it. They spend a lot of energy trying to mold it in ways that they would like it to be, and that seems to me rather futile.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you are such a Niebuhrian, aren’t you? I mean, what do you think Reinhold Niebuhr would be saying about what’s happening in America today?

MR. HEDGES: Well, he’d be appalled and terrified. You know, Niebuhr is often described as a Christian realist but he ardently opposed the Vietnam War. So I think, yes, I am very grounded in Niebuhr because I think Niebuhr understood human societies and he stood human nature and he understood that to make moral choices, not between moral and immoral but between immoral and more immoral. And when you don’t want to be tainted, and I think some pacifists can go this route, you work it in the same way that cynics do. You don’t make choice. And somehow it’s easier or cleaner for you not to make choice. But it is — you know, because we live in a fallen world, because we often don’t get to pick between good and evil but between evil and more evil, you know, we in the end have to tainted. It’s why Niebuhr wrote that when we make a decision, because we don’t know the will of God, we often don’t know the consequences of our actions, however well-intentioned, we must always ask for forgiveness and to be very frightened of hubris. And hubris, as the ancient Greeks know, can destroy us.

MS. TIPPETT: New York Times correspondent Chris Hedges. Chris Hedges is a veteran war correspondent and a Harvard Divinity School graduate. His book, War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning, is a graphic and brutally honest memoir of what he calls the narcotic of war, its power to thrill even as it corrupts. His final chapter is entitled: “Eros and Thanatos” — the Greek words for love and death. Ultimately, Chris Hedges says, the struggle between love and death is what all life consists of, the lives of individuals as well as the lives of nations. Yet even as he describes the human capacity for love as the only antidote to war, Chris Hedges remains wary of religious voices that romanticize human virtue and become ineffectual critics of war.

MR. HEDGES: Today’s victims can very swiftly become tomorrow’s victimizers. But that’s very hard to swallow because there’s a human tendency to laud and exalt the oppressed and give them values and qualities that we wish they had but which they don’t have. And when you can’t do that, it becomes much harder to report and to fight for justice because you realize everyone’s tainted.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I think for me, something that I value in theology — and I don’t feel like the press gets this either — is that theology can contain this complexity; maybe that’s also because religious voices don’t present it always as you’re describing.

MR. HEDGES: Yeah, I think that great — I mean, it — not only can great religious thinkers deal with the complexity, they finally are the only people who can give you the vocabulary and the framework to cope with it. I think, you know, the problem, of course, is that those kinds of thinkers are few and far between and usually very lonely figures. But I when pressed, and I certainly found this when I was writing the book, when I had to, and I tried very hard not to use theological language, but there were moments when I had no choice…

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. HEDGES: …speaking about grace, speaking about redemption, speaking about forgiveness, speaking about sin. You know, that — I had to come home to that.

MS. TIPPETT: And repentance…

MR. HEDGES: And repentance.

MS. TIPPETT: …is another word you use.

MR. HEDGES: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. HEDGES: Because I think at its core, you know, when we wade through the interpretations by theologians and the distortions imposed upon religious writings by religious institutions and I do think that deep down at its core, there are great religious thinkers who do get this complexity, who do understand it.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. The theological language in your book jumped right out at me. Journalists don’t…

MR. HEDGES: They don’t want to touch it.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. HEDGES: And — not that it’s that profound, but they don’t want to go there, and it doesn’t matter whether they’re reviewing it or talking about it, people don’t want to go there.

MS. TIPPETT: How are you understanding that fact?

MR. HEDGES: Because I think they’re uncomfortable with it and because it doesn’t fit, I think, with that, on the one hand, I certainly understand the world and I know how it works, but I believe in the power of love and not in a hokey kind of way. I certainly saw that those people in conflicts who were most able to resist the insanity of war and find an identity outside of the nationalist cause were couples that had — that were in love. And, you know, they were the people who rescued people from other ethnic groups. You know, I wrote a story about a Muslim farmer who, for, I think 400 days or something in the seize of Gorazde, brought a liter of milk every day to a little Serb infant that would have died without it. And very soon, the people in the apartment block would see him come up in the morning and insult him and spit at him and revile him, but that act that he carried out was a kind of witness to everybody in that apartment building, that Serb family, the father had been probably killed by the Muslims in Gorazde and whatever anger the parents had and the widow had, nevertheless, they could not demonize an entire people because of that one man. And some little girl — Serb girl is going to grow up, and she may never meet that farmer, but she’s going to know that she owes her life to that farmer. So when you look at the way an act of compassion or love which recognizes the divinity and the sanctity of the other, even your enemy, resonates beyond a war zone, it does have an immense power far more than it looks in the moment. And that I have seen in war, and that alone finally gives me hope.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if even some of the healing that you are concerned about, that happens among peoples and nations that have been in war, is it more difficult for Americans to take part in because we’re so far away from the war? I mean, how are you thinking about living in love while your country is at war right now? Give me another example of what this Christian virtue or this moral virtue of love might look like in America right now.

MR. HEDGES: Well, I think it will become very discernable, probably very quickly, if we suffer another terrorist attack, which just about everyone I’ve interviewed seems to believe we will, we will turn even further on Muslims in this society. You know, in many ways, the new anti-Semitism is anti-Muslim. And it will appear by having the courage to speak out and affirm the tradition of Islam, the dignity of Muslims, the innocence of those who have not been found guilty of a crime. I mean, it will manifest itself in a very concrete way…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. HEDGES: …by fighting what I suspect will be racial intolerance towards Muslims. You know, part of that would be by recognizing the divinity of the other, it becomes very hard for us to exalt ourselves above the other. By confronting our own capacity for atrocity, by striving not for the crushing of dissent or the crushing of opposition so much as a world where there is a modicum of justice. And until there is a recognition of the suffering of the other and the divinity of the other, until ultimately there’s forgiveness, there can be no new narrative.

MS. TIPPETT: And we’re back at that word repentance, I think.

MR. HEDGES: It is repentance. And Abraham Lincoln wrote about this. I mean, it’s such an important part of what it means to exercise power with any sense of not only justice, but the injustice that is always committed when you use violence, even for a defensible cause, and we’ve lost that. They used to have a great professor, Coleman Brown — we went to undergraduate, Colgate — who said that for every intellectual faith, there’s an embarrassment. And by that he meant that when you look at the world in the way it is, to have faith, to believe in the power of goodness oftentimes doesn’t square with the reality that you face. But I think in the end, to abandon faith, to succumb to the seductiveness of moral disgust, to cynicism, is a way to wash our hands of the responsibilities that we have, the moral responsibilities that we have. And at that moment, the world becomes a far more dangerous place than it is now.

MS. TIPPETT: Chris Hedges’ book is War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning.

Earlier in this hour, you heard just-war theorist Jean Bethke Elshtain and Harvard minister and professor, Peter Gomes. These individuals take three very different approaches to the war on terror and in Iraq, but together, they insist on the seriousness of using religious arguments for war or peace, how immoral inaction can be in the name of peace but also how thin the line between just and unjust war. Taking religion seriously at this time in our national life, they suggest, requires critical analysis of our action and that of our government. And they agree that there is always a moral cost to war with which faith challenges us to reckon.

Please let us know what you thought of the ideas presented in this program and if you’d like, send us your reflections. You can write to us at [email protected]. You can also contact us through our website at www.speakingoffaith.org. While you’re there, you’ll find book and music lists, relevant links, and you can listen to this program again as well as our previous programs. You can also call Minnesota Public Radio at 1 (800) 228-7123. We would love to hear from you.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections