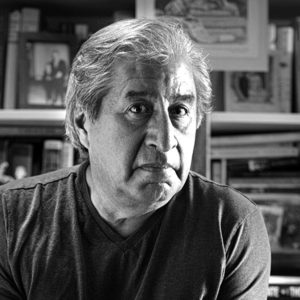

Richard Rodriguez

The Fabric of Our Identity

After September 11, 2001, Richard Rodriguez traveled to the Middle East to explore his kinship, as a Roman Catholic, with the men who stepped onto airplanes and turned them into weapons of terror. What he learned illuminates some of the deepest paradox and promise of the world we inhabit. He is an especially intriguing conversation partner for right now — a life and mind straddling left and right, religious and secular, immigrant and intellectual. At the Chautauqua Institution, we mine his wisdom on the emerging fabric of human identity.

The fourth in a four-part series, “The American Consciousness.”

Image by Naufal MQ/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Richard Rodriguez is a journalist and essayist. He won a Peabody Award for his original commentary on The NewsHourand received the National Humanities Medal in 1993. His books include Hunger Of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez, Brown: The Last Discovery Of America, and Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography.

Transcript

September 18, 2014

RICHARD RODRIGUEZ: The first thing I understand is mystery. And, I moved to the great desert of the Middle East. And I realized that the God of Abraham, who is the God of the Jew, the Christian, and the Muslim, revealed himself in the desert. God intrudes in a moment. He revealed himself that day, that moment. Well, he also reveals himself in that place. Well, what is that place? It is sand.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: After September 11, Richard Rodriguez traveled to the Middle East to explore his kinship, as a Roman Catholic, with the men who stepped onto airplanes and turned them into weapons of terror. What he learned illuminates some of the deepest paradox and promise of the world we inhabit. He is an especially intriguing conversation partner for right now — a life and mind straddling left and right, religious and secular, immigrant and intellectual. In this second episode in our “American Consciousness” series, we mine his wisdom on the emerging fabric of human identity.

I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: Richard Rodriguez is an acclaimed writer, best known to many for his years of original commentary on the PBS “NewsHour.” He was born in Sacramento, California, the first-generation child of Mexican immigrant parents. His lyrical writing embodies the way particular human experience, articulately recorded, can reveal deep truths about what is enduringly human and universally animating. His books include: Hunger Of Memory; Brown: The Last Discovery Of America; and in 2013, Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography. We spoke in the outdoor Hall of Philosophy at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York.

MS. TIPPETT: So, I start every one of my conversations, um, whether I’m with a quantum physicist or a journalist, uh, with this question, which is a question you’ve explored in great depths in your writing. Would you tell us about the religious and spiritual background of your childhood?

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Uh, it was total. I grew up, uh, Roman Catholic. Though that doesn’t even do it justice. I grew up in Sacramento, California, in a neighborhood, uh — I hate to use the term white, ‘cause white doesn’t tell me anything. White doesn’t tell me enough. White doesn’t tell me that your father was a coal miner. Uh, white doesn’t tell me that your son died in a canoe accident. Um — but it was white.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Um, and I went to a Catholic school where everyone was Catholic, with one exception, Bobby Wright, who was Episcopalian.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Uh, and he would bow his head when we prayed. And I was surrounded by Irish voices. Those were my first English voices. And that’s how I learned the English language, through Ireland, oddly enough. Um, all the priests, all the nuns, were Irish. This is Mercy were the nuns. And I dedicate Darling to them, um, because they were truly the first feminists of my life. But the remarkable thing was that from an early age, I was also an altar boy. That is, I was on the altar responding in Latin to the priest. Uh, and to this day I remember at a graveside helping to carry a coffin to the open pit. And then going back to arithmetic class in an hour. You know. The seamlessness of that life.

But I remember also, this is the power of memory, the power of poetry to instill itself on a child’s imagination. Um, [speaking Latin] those are the first lines I say in response to the priest. I will go to the altar of God, the God who gives joy to my youth. So people ask me now, you know, what was the church to you, um, it was completely embracing. And total.

And it began, at an early age, and just grew in mystery and majesty. We had, uh, Mozart masses. And there was this sense that I belonged to this European civilization. At the same time that I would go back and read Mark Twain, who refers to Romans and Papists as, you know, aliens in some sense, um, or Henry James, who goes to Europe to meet a society that was already mine in Sacramento. So it was like living two seasons, summer and winter. There was the Church, the Catholic Church and then there was America. The America of Mark Twain and Henry James.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, there’s this, um, line in your memoir, Hunger of Memory, that I thought was so striking. You said, of all the institutions in their lives, only the Catholic Church had seemed aware of the fact that my mother and father are thinkers, persons aware of their experience of their lives.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes. This is — I think this is the power of liturgy and ritual, the seasons of grief and triumph, the seasons of renewal and sorrow. Um, the power of religion to make us reflective of the lives we are leading seems to me to encourage an inwardness, which I would call intellectual. And when I think of what the peasant Church, all over the world, is still able to give people is that same consolation of the inner life, no small gift.

MS. TIPPETT: No.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I must tell you, Krista, I lived most of my life now among people who are not religious, people who are anti-religious. My brother considers himself not an atheist, but an anti-theist, uh, he says that the word atheism doesn’t grasp the fullness of his negativity toward religion.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Um, and so when I write about religion as I do, I’m always worried about what the secular reader is going to make of this line. The worry I have is always that, um, you know, that my writing will be too pious, uh, for the…

MS. TIPPETT: For the secular.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: For the stylish, I’ll call them.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Or too stylish for the pious.

MS. TIPPETT: I just want you to know everybody here is stylish, too, it’s just that it’s summer and they’ve let their guard down.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: You know what I mean. There’s just a — that the uses of irony and paradox are not always apparent in religious, uh, writing.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, we’ll probably come back to that. I want to talk about your — I want to kind of — again the beginning — the trajectory of your life and what you’ve learned. And sort of what this theme of the American consciousness, you know, here’s another observation you made, that Americans like to talk about the importance of family values, but America isn’t a country of family values. Mexico is a country of family values. This is a country of people who leave home.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And you — in your childhood, um, had to leave home linguistically and intellectually, in order to unite your private and public selves.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah, when I announce that I’m going to college, uh, Stanford, uh, immediately my mother is worried, you’re not, you know, in a way that maybe, you know, Appalachia would understand this, the betrayal of education. That I’m going away from the family. That I’m going to get ideas that are too big for me. That, uh, that I’m going to begin to reject my own culture. And in fact, it happens. Uh, education is a subversive influence in our lives. We don’t realize this, especially because so much of education is dedicated to class mobility. We don’t realize at how much a price that working class families pay psychologically to have their children leave home.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, the whole family.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Hm. And something so striking to me, again, in the trajectory of your life, is that you grew up, as you described a minute ago, being so aware of being brown in a white world. And needing to join that white world, um, to become your fullest self. One of the themes that you’ve been writing about and talking about here in the 21st century is that the color of your skin, brown, in all its variety, is the new color of American identity. You even say Barack Obama is not the first black president, he’s the first brown president.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Well, I think that, you know, if you — I think that would have been stunning if we had understood what his brownness from the beginning. That there is in this man, you know, both Kansas and Kenya, that he is — he’s mixed. That whole idea of being mixed is very difficult for Americans. We have, on the one hand, this notion of the one-drop theory. That if you have one drop of African blood, you’re black and so very, very light skinned people will tell you, well, I’m black. And I keep thinking, well, maybe I’m not getting enough sleep, you know.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Uh, or people say, you know, I’m white, and many times they have such different colors. A lot of white people are pink, and orange.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And, um, and at the end of summer, a lot of them are brown, but…

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: …they don’t say that. They say that they’re tanned. Uh, but that inability to deal with mixture, I think, is part of the American anxiety about individuality and I think we don’t realize the complexity of people that have created us, complexity of civilizations. I was created by Spain, and by native societies in the Americas. I carry on my face the Indian nose, the Indian mouth, all my religion came from Spain. My first language, Spanish, came from Spain. But there is obviously something in me of the Indian that I have to account for. For me to say that I am one thing in a place where I am many things. Um, every point I have is to realize the complexity of my life. And it is not exactly true that I grew up in a white society.

My Mexican Aunt, uh, Lola, married my uncle from India, Krishna, at a time in California where, um, the restrictions on immigration were such that Indian men could not bring women into the country. So there was a lot of Mexican-Indian marriage — intermarriage. So, that I was quite accustomed, as a child, to turbans, and Hindus. Uh, my uncle’s sister, uh, Ruth Gupta, who became a big landowner in San Francisco, when she died, Dianne Feinstein was at her funeral. But I can remember her lifting her hands over the turkey at Christmas and chanting the Hindu hymn. And the turkey did not flinch.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: So, but this is so interesting to think about, because it’s always been true, and it’s certainly always been true in America that we came from many peoples and many places. This complexity was — there’s some Cherokee in me, which doesn’t show. Um, uh, I mean I think what’s happening now is that physiologically, the mixing has started to show on us.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes, and I think also…

MS. TIPPETT: And so there’s a shift in consciousness, I think you’re saying, you know, this is changing us from the inside out on another level as well.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I think something else is going on, too. I think that we are living in a society — my optimism about this moment is that people are falling in love all over the place. Uh, this is one of the great civilizations of love. It drives the churches crazy, of course. Uh, because they don’t want to lose their members, and the purity of line. And because they’re — they also — the church — my own church would not give me the word love to describe my relationship to another man, with whom I’ve lived for 35 years, but that’s another point. Um, there is now, not, you know, I remember the nuns saying, uh, to us the dangers of mixed marriages, by which they did not mean racially mixed, but the danger of marrying a Methodist, you know.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: So now I get a letter from a young woman, um, uh, on starched, white stationery yet, uh, no email, uh, she sends. And she says in the first sentence of her letter, she says that, uh, my mother is a New York Jew, and my father is an Iranian Muslim. And I think to myself, well, that’s very brown, uh, to be a Jewish Muslim. And then she says in the second line of her letter — this is a true story. She says most Americans think that I’m a very frugal terrorist.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I’m telling you — I’m telling you there are things going on religiously in America that our religious institutions are bewildered by, people who belong to more — more than one faith or Catholics who call themselves Zen Sufis. I mean, uh, it’s within the complexity of that, is the brownness that may envelop us. Now I warn you also that there are purifying movements in the world. Look at what’s going on in Iraq right now, where the nation divides over separations — ancient separations that we thought we had gotten over.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Where even in single families, where there was mixture, there suddenly is separation. And in many movements now, this desire for purity, uh, the skinhead movement in America. I’m going to go up to Idaho and I’m going meet only white people like myself. You can keep L.A. You can keep the DMV in L.A. with all those languages. I’m going to live in a pure section with pure water, with pure air. I’m going to live in this little corner. Well, that dream of purity is very much alive at exactly the moment when everything is mixing.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: in a live conversation with journalist and essayist Richard Rodriguez. We’re in the outdoor hall of philosophy at the Chautauqua Institution in New York in a week devoted to exploring the American Consciousness.

MS. TIPPETT: And you took yourself on a really fascinating journey. After September 11, 2001, which was a moment in this culture where we absolutely saw this dangerous “Other.” I mean, Islam — this religion of over one billion people — had been there all along. But we saw this terrifying face of the “Other.” And you made this, I would say, in that context, countercultural move of exploring your kinship with these men who were terrorists. I mean, you wrote — you realized, “I worship the same God as they, in this, as a monotheist. So I stand in some relation to those men.” And you set out to understand what had happened in that sense.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Well, the first thing I understand is mystery. And that is, I moved to the desert, to the great desert of the Middle East. And I realized that the God of Abraham, who is the God of the Jew, the Christian, and the Muslim, revealed himself in the desert. You know, the distinction that these religions claim temporally, is God intrudes in a moment of time, of the eternal God becomes temporal. He revealed himself that day, that moment. Well, he also reveals himself in time — in place. He reveals himself in that place. Oh what is that place? What is that place that the Israelis and the Palestinians are fighting over? It’s sand. It is desolate sand.

It is in some places, there are deserts in Saudi Arabia that are as lunar as anything I expect to encounter in my life. This is a holy landscape. It is also a landscape that drives us crazy. Somehow the — in this landscape, we got the idea that there is a God who is as lonely for us as we are for Him. And there is in this landscape, also, a necessity for tribe. Not for — you do not live as an individual on the desert. You live in tribes. And that tribal allegiance, that tribal impulse, leads on the one hand, to great consolation, but also to the kind of havoc we are seeing now. I have a chapter on Jerusalem as the great desert city, but also, this — our own American desert city, which is Las Vegas.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: Right. That’s what we do with desert.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Well, when I say…

MS. TIPPETT: That’s what we do with desert.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: When I said the deserts drive us mad, I mean Las Vegas. That there is something about the desert that terrifies us. So Las Vegas gets this idea of playing with that idea of death. It most — since everything is an impermanent, that I’m just going to move — Eiffel Tower, don’t you — to across the street from the pyramids.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Um, and that nothing, you know, I’m going to roll out a carpet of golf green over there, and Olympic-sized swimming pools.

MS. TIPPETT: It totally defies finitude and frailty, doesn’t it?

MR. RODRIGUEZ: That’s right. But the interesting thing, though, is that it spread — that Las Vegas-ization is spreading out to the Middle East. I speak of the city like Dubai, for example. You go to the hotel and the woman says, we’re going to upgrade you to a suite on the 185th floor, and you open the windows and there is a desolation out there. But don’t worry about that. You can go downstairs to the ice palace and you can have a snow, uh, snowball fight in the ice ballroom. Now, Mecca is becoming Las Vegas. There is over the Kaaba within sight of the Kaaba, a vast hotel built in the shape of Big Ben. Where did they get that idea, except for Las Vegas? This enormous hotel, I think it’s run by the Fairmont Hotel chain. At the bottom of the hotel chain, there is a super mall. So there is in the middle of the holiest space in Islam this invasion of place of what the desert is. This is where we were meant to encounter God. You understand what I’m saying to you? Not the glade. Every Christmas, I’d get these Christmas cards that make it appear that Jesus was born in the Swiss Alps.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And the evergreen tree has all these little sparkles to it, you know. It’s so funny. It’s desert. The three great ecologies of these religions are mountaintop. And finally, finally, and most profoundly, the cave. You have to acknowledge when you wander the desert, how bright and blinding is light. And how consoling is twilight and darkness. In these religions, oftentimes shade and darkness come as consolations, or gifts, so that Mohammed has his revelation in a cave, in the darkness. In Judaism, God puts Moses in the mouth of a cave so that he will not be blinded by the brightness of God. And in Christianity, the two most holy events of the — of Christ’s life, the birth of Christ, which happens in a cave, and the death of God — the death of Christ. And also the resurrection happened in a cave. We sometimes forget it because we are consumed by a kind of a Hellenistic dream of coming out of the cave with Plato, and into the sunlight, that we are people of dark.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you…

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And we should accept that darkness as part of our faith.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I guess that leads into what I want to ask you. I mean how did you come to realize how the desert in this tradition and the cave, how these things had formed you, um, the Catholic spirituality that you find to be redemptive.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Well, the deepest, I mean, the most radical Catholic spirituality I know of, is Spanish. And it’s a mystical tradition of the dark night of the soul.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Um, we often, you know, I end this book with Mother Teresa, who was, um, hounded by Christopher Hitchens, our great American atheist going from cable channel to cable channel to tell us God was dead. Um, at a time in which — I live part of the year in London. And I assure you, God is not dead in London. Muslims are plentiful, as are Hindus. Uh, but nonetheless, Mother Teresa, after her death, these letters, uh, to confessors and bishops were revealed. For 40 years of her life, Mother Teresa describes her life as a darkness. And there she is, more and more famous in the world, uh, mocked by Christopher Hitchens in the pages of Vanity Fair magazine. I mean, In Vanity Fair magazine, Christopher Hitchens tells us that Mother Teresa is ugly.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And I think to myself, what is that? What is he playing on in America that you can say about a pious old woman who is bathing the dying in Calcutta. What is that?

MS. TIPPETT: And in the end of your book, you do, you have this huge journey and you — and I wanted to ask you why you ended there, because you do end with the juxtaposition of Christopher Hitchens, with his exuberant certainty that there is no God…

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …and, um, to the very end of his life, and Mother Teresa, in her despair.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I once was with her in San Quentin prison. We weren’t prisoners, but we were visiting.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And she — it was the most remarkable afternoon I’ve — I can remember, religiously. Uh, she was — there was a group of thugs and she was supposed to meet these guys from death row and they were all like schoolboys. And this tiny little woman, you know, four foot tall or something in her sari. And then listen to this. She tells them in that little tiny voice, she tells them, if you want to see the face of God, look at the prisoner standing next to you. These tattoos coming up over their necks, look at the man next to you. This man who has murdered and raped. That’s the face of God and I think, oh, I didn’t know that. I didn’t know. I’d been looking at the holy picture all this time when I should look more closely at the face of the sinner to find the face of God.

[Music: “Hungry Face” by Mogwai]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Richard Rodriguez through our website, onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Hungry Face” by Mogwai]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today, in the second episode of our “American Consciousness” series, we’re with Richard Rodriguez. He is one of America’s great observers of self and society. His life and mind straddle discourses of left and right, of immigrant and intellectual, of secular and religious. We spoke at the Chautauqua Institution’s 2014 season, before an audience in the outdoor Hall of Philosophy.

MS. TIPPETT: I do want to talk about immigration, which is also a very painful and open subject in…

MR. RODRIGUEZ: It’s an opportunity.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Uh, for Christians, um, Christians, I’m telling you, um, it is noticeable, the silence of American Christians on this issue. Uh, it is quite clear to me, what the gospels tell us to do with the stranger in our midst. But there is something in this obliviousness that is very worrying, particularly in a time when the American churches, Christianity particularly, would be in decline numerically were it not for immigrant populations coming into this country. The Mormon church, now, which is the fastest-growing, uh, church in the country, is in its majority now, primarily Spanish-speaking. The Southern Baptist now are becoming increasingly Hispanic in their membership. At a timing which there — these churches are seeing the growth of these populations, within their own pews, you would think that some of the leadership would speak for this, for example, the children at the border. Where are the Christians in all of this?

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: And you know, I think there are Christians and religious people in those places where some of this drama is playing out with the children, for example.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I do too.

MS. TIPPETT: And they don’t get covered in such a high profile way by my fellow journalists, which is something I’m always aware of.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, you have, though, some really particular insights into this border, this Mexican-American border, which so defines us, but I think we tend to be oblivious to it a lot of the time, until something blows up like this. Um, I mean, you’ve talked about the psychic tension between Mexican stoicism and American optimism. Can you talk about that dynamic?

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Well, I mean, the — can I say something about drugs, uh, in this culture? Um, what Mexicans will ask me all the time, Mexican relatives of mine, why are the Americans so unhappy? I don’t know what to tell them. Why are we taking it up our nose and putting it in our veins, and — when we can’t be alone without drugs, we can’t be with other people without drugs. We can’t have sex without drugs. We can’t go to sleep without drugs. We can’t wake up without drugs. We can’t get out of bed without drugs. What is this addiction? We have destabilized much of the world with our addiction. We’ve — we have created a drug economy in Afghanistan, in Thailand, in Bolivia and we’ve caused turmoil in Guatemala and now we have elevated thugs in Mexico to the status of billionaires with our despair. And yet, we are an optimistic people. And yet, Mexico, by comparison, is a tragic civilization in which death is very much a part of the — of one’s understanding of what life is. The paradox of the border right now, is that you see young people coming to the American border for the opportunity of America, at exactly the time when Americans are importing drugs from Latin America because of the despair of our unhappiness.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And it — the paradox of that movement in both directions is so interesting to me and so little noted, but it is — why don’t we talk about difficult things? The book I read as an American kid and the nuns told me it was the great classic of American literature, was the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. This romance in America of being on the move of leaving home. Well, there they are. They’re seven and eight years old and they’re at their border and we’re horrified by them now because we don’t even recognize our own myth.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you just — you’ve named a couple of really important things in the last few minutes and I think you’ve also named the important fact that we don’t have a vocabulary for talking about what’s really at stake here. We can sometimes define these things in terms of policy, laws that we might take. And, you know, so I want to come back to something you — wrote about or spoke about when you were actually commenting on how we, in the last 20, 30 years, well, actually before that, consigned religion to the sidelines. And then what happened in the last 20, 30 years is we had a few strident voices who emerged. We kind of gave it over to them, which made almost everybody else get really quiet. Um, but you made an observation that is relevant to this beyond that specter, you said — what you ask, you know, “What’s happened to us — and I would include myself on the cultural left,” you say, “is that we have almost no language to talk about the dream life of America, to talk about the soul of America, to talk about this mystery of being alive at this point in our lives, this point in our national history.”

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah, I — can I say because it’s the churches. Can I say that one of things that concerns me about religion right now is how little we understand who we are. For example, I — since I’m in England, there’s a neighborhood Anglican church and they try to be very hip and try to bring in young people. And they put the book of common prayer on a Kindle machine. And I think to myself, do they not understand that these religions — the Abrahamic religions were religions of the Word. Are religions of the Word and that they — that their power is in the weight of the Word. The Word became flesh. You understand? And it is something carried in the Bar Mitzvah, in by the child, the weight in its hands, it is kissed, it is revered as weight. That is — it enters history and we seem as Christians, well, we sort of understand that, but we sort of don’t. I tell Jewish audiences, if I ever go into a Bar Mitzvah and the kid comes in with a kindle, I’m getting out of there.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: You — you’ve also said, and we don’t have time to get into this now, but that the — what the desert of California has done by innovating cyberspace and pushing on to cyberspace is just an extension of this American preoccupation with pushing back the horizon, pushing back the boundaries.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes, and ignoring where we are. We’re in the middle of an intersection, the bus is coming right towards you, but I have to chase — check my Facebook account, you know.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: This obliviousness — it — we have it backwards. Henry Ford did not invent the automobile, we invented Henry Ford. We were anxious. We needed to get away from the house. We wanted to get away from our in-laws. We wanted cheap transportation. So we invented Henry Ford who gave us Model T Ford.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: We did not — we invent — we were stuck in the suburbs. We were lonely. We didn’t want to deal with the mall anymore. So we invented Steve Jobs. He gave us this technology which would allow us to go — to talk to anyone in the world without leaving our room. Would allow us to shop anywhere in the world. We don’t have to deal with crowds anymore. We can just push buttons. You have to acknowledge with what there is about human anxiety that has created this technology.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: What is it that it is trying to meet? What is that? Is I guess is what I’m asking.

MS. TIPPETT: And I think that’s another large question that we need to be sitting in the middle of our common life and we need vocabulary to grapple with.

So I’m going to ask one more question, and please come up if you have a question, if you’d like to join the conversation. Um, you know, you’ve been controversial over the years for, uh, saying that bilingualism is not desirable. You, um, — that the language of the minority, which was how you understood yourself, is inadequate. That, you know, that affirmative action is problematic. You know, it seems to me that our entire way of grappling with difference, which we really only started to grapple with in this country in the 1960s. You know, we enshrined the civic virtue of tolerance, and it’s not nearly big enough. And I wonder if, you know, you’ve been talking about these kinds of things for decades. Uh, you know, I wonder if many of the things we invented in these early decades were all half-steps. And if you see — how you see — do you see us evolving into something richer and more adequate?

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Uh, I have to say yes, because I believe — I have faith. Uh, but I also think that there — the word diversity comes from the word divide. So when you’re talking about celebrating diversity, are we celebrating the fact that I am not you? What am I celebrating? It seems to me that the Christian impulse is not diverse, but it’s to seek a commonality.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, but, I mean, that move you made after 9/11 when you talked about you — you abhorred that act of terrorism, but you had to understand your kinship with those men.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yes, and I — I’m so — here I am in Cairo, in this foreign city, and I keep hearing the Arabic around me, which I can understand a bit, but not so well. Um, and it sounds Spanish to me. And I think — I said to myself, I say it to a friend of mine, I said, why is there so much Spanish in Arabic? And they said, that isn’t Spanish and Arabic, that’s — what you don’t understand is that there are three to 4,000 Arabic words in Spanish, because Spain was once a Muslim country. And then he says, and will be again.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: But then I remember my mother, my Mexican mother, standing at the door on a rainy day, “Ojalá,” she says. Ojalá which means in Spanish, “let’s hope.” “Ojalá all the clouds are coming, it won’t rain this afternoon.” “Ojalá the sale at Penny’s will be on this weekend and I can get you a new jacket.”

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Ojalá, and I did not hear for the thousands of times that I heard that expression, I did not hear the name of Allah on her lips. O-ja-lá, it came from the 16th century. And there are things we talked about the genetic blood that we carry of ancestors and tribes, people are paying $450.00 to get their DNA checked, and they’re finding out that they belong to civilizations their grandparents told them nothing about. Well, linguistically, too, we belong to civilizations far away, and what I began to realize, of course, is that the Muslim is within me and it certainly was on my mother’s lips.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: in a live conversation with journalist and essayist Richard Rodriguez. We’re in the outdoor hall of philosophy at the Chautauqua Institution in New York in a week devoted to exploring the American Consciousness.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Let’s invite you in. Yes.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: Hi. Uh, I am particularly interested in looking at the intersection of religion and faith, and homosexuality. So I would love to hear you reflect just a bit about what that’s meant in your life, given the religion you were born into and who God made you to be.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Um, when I speak before Catholic audiences invariably now, a man will come up to me afterwards and will say, my son is gay. A word that I don’t use, by the way, um, because I’m morose. Um, but, uh…

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I wasn’t sure you’d get that.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Charlie Rose once asked whether I’m a gay writer and I said, no, I’m a morose writer.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: This expression being gay is so — it’s like a little sparkler at the Fourth of July or something.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Anyway, um, you know, one of the things I don’t think we really, as a Catholic, I was surrounded by an iconography, which was luscious and physical, and there was the bleeding Christ on every cross that I ever saw. And the eroticism of the religion was, to my imagination, very, very rich from an early age. At some level, this church which denied me also gave me a great deal. I want to be clear about that. Um, I do not want to present myself in any way as oppressed. It did teach me, and this is the point of Darling. I’m — Darling in the book is not Richard Rodriguez. Darling in the book is a woman, a friend of mine, who has lunch with me in Malibu, California, on the day her divorce was finalized. She has since died of cancer. The chapter really is about women and religion. And I think that I came upon that theme, that subject, because I am gay.

Uh, I don’t want to talk about myself. But all I want to say to the Christian churches, is that the man that I’m with, I will say not even — I won’t even give myself the grandeur of this word. But his achievement and his importance to me is that he has loved me. And he has taught me the import of that word. The church will not give us that word. I date my emancipation as a homosexual man with the women’s movement. And I notice that Susan B. Anthony came to this place to argue for the vote for women. When women begin to call for the vote, it is a revolutionary act, and it liberates me.

And I’ll tell you how. For the first time, women are saying I don’t want to be identified merely with what I am at the house. In civic society, I don’t have to be somebody’s mother, or wife, or grandmother. I want to be judged equally with any man in the voting booth. And when women get the vote, they move out of the kitchen in something like the way that they allowed me several decades later, to move out of the closet. These movements are related to each other. I cannot imagine my freedom without women.

[applause]

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Thank you for that. Uh, I, uh, self-identify as a cultural Jewish faithful Unitarian Universalist.

[laughter]

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: But, nonetheless, or possibly because of, uh, I want to go back to the comments that you made, uh, addressed to this largely Christian community about the lack of leadership of presence at the border, uh, involving the deportation of children and the larger immigration questions, which we Americans are not doing well with, to say the very least. And I wonder if you would comment on, uh, a theory that keeps on boiling in my own head about the paralysis of the former Protestant mainline leadership. And whether it is consciously or probably unconsciously due to the fear of the impending death of white hegemony.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: That’s — that, pretty interesting questions. Uh, I do think that we have allowed — there’s a religion in this country, and it’s quite powerful, if you are an immigrant child, because you know that it exists. And I’ll call it Americanism. And it has great charm. It has great bravery. It has great grandeur. And it gave me great freedom. But it is not exactly my Christian faith or my Jewish faith.

Uh, I am taught in my religion, things that are not exactly the things that America teaches me. I am taught in my religion that, um, that I will fail, that I’m a sinful creature. I heard it this morning. I am taught in my religion that, uh, that I can’t make this alone. That I need you. I’m taught in America that my strength is as an individual. That I have to leave home. I’m taught in this country contrary things, is what I want to say. And in some way, I think as we became — certainly I’ll say this about Catholics. As we became more and more mainline, we became afraid to say that we were in some way alien to the culture. In some way quizzical about it. That’s what worries me. That we have sort of turned our Christianity, our Jewishness, into something, what shall we say? Uh, polite and nice. OK?

I mean, uh, there’s only one solution to the problem of immigration. That is that, uh, you should have a law, a new amendment to the Constitution that says that you have to leave this country after three generations.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Because quite clearly the vitality of the country comes with immigrants and their children and it begins to wane. I’ll tell you, I’m nowhere near as interesting as my mother. I swear to you.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And, I mean, she ended up typing in Governor Brown’s — Edmund G. Pat Brown’s office, uh, for a while, until she was fired because she mistyped — she heard on the — on the Dictaphone a reference to urban guerillas and she thought it was the animal. So she typed in urban gorillas, and so she was reassigned a job.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: But, um, I said to keep this country the country that — of the 19th century, this country that — of this village, if you want to keep that country, you should send everybody who’s been here for more than three generations to Australia or Costa Rica or someplace. But this country has — I saw a picture, I think it was in The New York Times, of this little boy swimming with his sister. He must have been about 10. She was about 7. And I thought of their bravery, their extraordinary bravery in making that recklessness, their flirtation with danger. And I thought, God, a country that beckons these people, that’s the country I’d like to live in.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: Two brief comments. Uh, Dr. Unger talked about the fact — and you’ve alluded to it indirectly, that we have no prophets anymore. That we’ve lost our prophets. There’s nobody of any substance who speaks as the prophets used to speak. And I’d like to hear you address that. Also, I’m from Austin, Texas, and I doubt many people here know that the Dallas County judge has opened the city of Dallas to 2,000 children.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I did…

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: Uh, he’s supported by the churches and the schools.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Good for him.

[applause]

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: And we’re — yeah. We’re trying to do something similar in Austin, and I’ve talked — I’m a physician, a retired physician. And I’ve talked with some colleagues and — and we’re committed to — if the kids get to Austin, we’ll take care of them. So there are things happening.

[applause]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: But let me say — just in response to the question about prophets. I think this country has plenty of prophets, but most of them are false prophets. Uh, the seriousness with which people give now to our political commentators, at a point when our political life is in shambles, uh, you get the leaders you deserve. I say this to Catholic audiences, you get the priests you deserve. We get the prophets we deserve. Look around you. Look around this country at the people who can change the country. There are, you know, I’m often puzzled why we have decided you pay for television. You pay for who’s on and who’s off. Why have we decided that tonight we’re going to hear a conversation from two dull people.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Uh, and that will constitute…

MS. TIPPETT: So, this crowd has obviously chosen an alternative.

[laughter/applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Um, I’d really like to get both of you in, but we need to be quick, because we have to clear this space out.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: I’m sorry. I’m — my answers are too long, so, my apologies.

MS. TIPPETT: They’re very — no, they’re great. It’s just — we have these limits. Yes.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 4: Uh, my question is I — you guys mentioned briefly before interfaith relationships kind of hinted at that. And I’m curious the differences that you might see between an interfaith relationship where, say, one person is a Muslim, and another is a Christian. And a relationship in which one person has a faith, say Christianity, and the other one is an agnostic or an atheist. Um, yeah, do you have any insights on the differences?

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah, I do. I think it’s both good and bad. The good is that I believe in brown — I believe that God has a brown face I believe that is — within the complexity, uh, that God is probably in a yoga position right now.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Um, but I also believe that, um, there is a difference between brown and beige. The hard ones are — if I say can you tell me the difference between a Methodist and Presbyterian? If — can you tell me the difference between Catholic and a Protestant? Uh, one has bigger churches? Uh, uh.

[laughter]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: The — and then you say, well this — they believe this, and they believe that. Well, that’s cool, they’ll say. And everything becomes beige. Nothing matters. You understand? I told this to a group of young, uh, girl students at a high school the other day, Do not be beige. There are some things that are non-negotiable. The mistreatment of women, for example, is non-negotiable. That’s not beige. You understand? That’s black and white and in some way, we have to be clear about what it is we believe. That the centrality is of love, of our experience as Christians. We either believe it or we don’t. Love, I’m not talking about marriage, the centrality of love and, um, that’s not negotiable. And when I come upon somebody whose values move in a different direction, I learn from them in many cases, that they’re not mine. And I’m prepared to say that.

MS. TIPPETT: You…

MR. RODRIGUEZ: That’s not my tradition.

MS. TIPPETT: I really think that the new generation coming up is going to learn and teach us to live with robust identities, and even convictions, understanding that the world needs their robust identities, but also, at the same time, that you want to live peaceably and creatively with different others.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And…

MR. RODRIGUEZ: That second — that — the capacity of the young to live with — with people who are unlike themselves, is quite stunning.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: And you see that now.

MS. TIPPETT: And they have a whole new set of instincts.

[applause]

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Just want to, um, actually I thought maybe, uh, it would be fitting, especially since the notion of prophets came up to — I just love this — these lines of Cesar Chavez that you had in your book. “I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness, is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally non-violent struggle for justice. To be a man is to suffer for others. God help us be men.” You noted, when you quoted this, that now we would — he would say, to be human is to suffer for others. God help us be human. But I mean, I don’t know. I just wanted to throw that out there.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: Well, I, you know, I got in trouble with that essay on Cesar Chavez, because I don’t make him a saint. Uh, I make him a human being.

MS. TIPPETT: And none of the prophets are saints.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: That’s exactly right.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RODRIGUEZ: The ex — you know, the brilliance of my Catholicism was always to acknowledge that we are failed creatures. Graham Greene writes a novel about Mexico in which the hero is a whiskey priest. Everybody else has left the village. Everybody has escaped. And this priest, who is a drunkard, comes and whispers over the chalice, the blood of Christ, [speaking Latin]. This is my body, and he’s drunk, but he’s both a failure and a triumph. Look for your saints accordingly.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I think that’s the last word. Thank you. Yeah. Thank you, Richard Rodriguez.

[applause]

[Music: “Safe In the Steep Cliffs” by Emancipator]

MS. TIPPETT: Richard Rodriguez’ books include: Hunger Of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez; Brown: The Last Discovery Of America; and in 2013, Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography.

[Music: “Safe In the Steep Cliffs” by Emancipator]

To listen again or share this episode with Richard Rodriguez, go to our website onbeing.org. You can also stream on your phone through our new iPhone and Android apps.

[Music: “Safe In the Steep Cliffs” by Emancipator]

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Chris Jones, David Schimke, and Bekah Johnson.

Special thanks this week to Maureen Rovegno and Robert Franklin at Chautauqua Institution, and to Mitch Hanley.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections