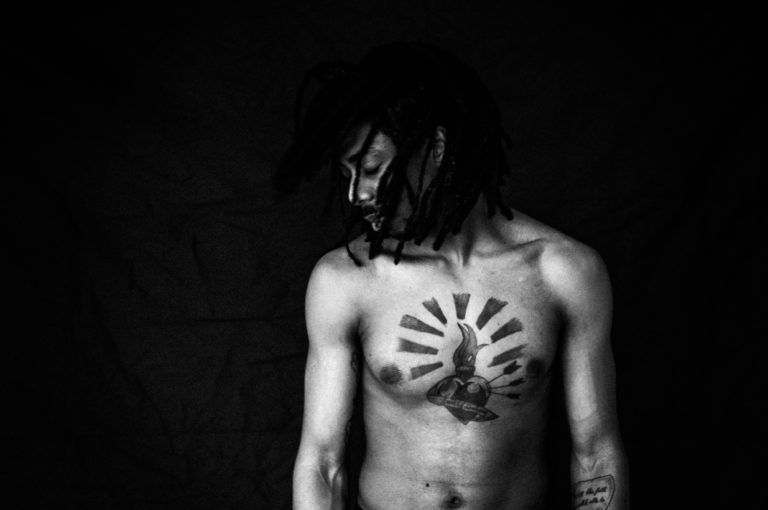

Image by Ben Raynal/Flickr, Some Rights Reserved.

Emily Dickinson’s Agility Training for Men

Emily Dickinson revolutionized American poetics. But, her contributions to men’s strength and conditioning are far less known.

Dickinson is a drill sergeant. She accepts no less than men’s revitalization. The rhythm of her verse is firm and athletic; her poetry is thew, a muscular force that generates physical strength in men rendered comatose. Dickinson applies the muscles of poetry to heal the injury of masculinism that lays men flat.

Practicing poetry as steadily as reps on the lat machine is the surprising new exercise that strengthens men’s bodies to get moving.

The regimen she put me through — poem, eat, poem, sleep, downing a handful of poems every morning like egg yolks for breakfast — created physical results rivaling those induced by any elite trainer. Reps of her poems expanded my body’s range of motion. It began to move in ways I never dreamed possible. Dickinson’s poems should be included among fitness tips in men’s health and fitness magazines.

Take, for example, the strength my quadriceps acquired to carry my body across the dance floor to kiss a man at a gay bar in Portland, Oregon’s popular Pearl District. I was 25, and my lips had never touched a man’s before. My heart had not yet built the endurance to marathon through my Midwest-born-and-raised internalized homophobia. By the time I had moved to Portland, I had been training under Coach Dickinson since high school. She knew I was ready to step up to the next level.

On this particular Saturday night, I saw the man with whom I had flirted the week before dancing with friends under kaleidoscopic lights. At first he didn’t see me. Without Dickinson’s coaching, his beauty would have been a weight too heavy for my gaze to hold. But my eyes held him, even as my heart shook like biceps lifting a chin over a pull-up bar. Christina Aguilera’s pipes swept across the dance floor, but all I could hear was my trainer’s voice:

Our journey had advanced;

Our feet were almost come

To that odd fork in Being’s road,

Eternity by term.

This advance across the dance-club crossroads was our journey, Dickinson’s and mine. Without her coaching, my hamstrings would have buckled, my heart would have lacked stamina to move in his direction. I panicked when my crush’s eyes lifted toward mine. It felt like chair pose in yoga when your thighs begin to ache. But I surrendered to the burn.

Our pace took sudden awe,

Coach Dickinson spurred me to quicken my pace, and suddenly I stood in front of him. The space held between us felt light. We began to dance face to face. Our thighs brushed as lightly as the first drop of sweat that falls from your brow in plank pose. My knees shook. I didn’t think I could stay in the pose, but Dickinson spotted me as at the squat rack:

Retreat was out of hope,–

Behind, a sealed route,Eternity’s white flag before,

A finish line appeared. I felt like a marathoner with nothing left but my coach’s belief in me:

And God at every gate.

I don’t mean to say that kissing a man for the first time was like crossing into Paradise. It wasn’t. But the exertion of kissing a man was, for me, an athletic feat of Olympic proportion. Some gold medalists say that winning is underwhelming. All that effort, struggle, self-doubt, and overcoming, for this moment, already over.

But in another way, kissing him was a paradise. Or, rather, the paradise was my increased range of physical and emotional motion: the freedom to move my face close to another man’s, to open my lips, to express this kind of tenderness to a man. A piece of armor around my heart clanked to the ground. I had become strong enough to leave it there.

Males, of course, have a long history of expanding their motion as a birthright. In Ohio, where I grew up, it was male prerogative to move and take up space with one another — but, paradoxically, in restricted ways. Like many places across the country, my town dedicated millions of dollars to sweeping a forest clear — to plow, mow, and manicure a football field for male bodies to move together.

This field gifted males the space to sprint, leap, and extend — to a point. Numbered lines painted across the turf disciplined young men’s masculinity: do not go out of bounds or else everything stops. Males ran fast and long, but armor and helmets preempted improvisation, twirls, or wheelbarrow racing with a partner. The man in uniform would blow his whistle and punish any transgression.

Off the football field, male-male touch was disciplined. Quick bro handshakes must last only so long. Thighs could touch, but only by accident.

Male bodies exerted themselves to find distance away from hands of other males — away from their shoulders, backs, and cheeks. A man who engages in combat with another man has a history of glorification in this country. But, a man who exercises affection for another man — who throws him to the ground and cuddles him — is considerably less revered.

Our culture’s valuation of masculinity — the favoring of a tough guy with hard edges over other varieties — gives men some prerogative to occupy space together, but that privilege comes with an alarming cost. Despite the entitlement to usurp space, widen stances, and claim turf, a man’s range of emotional and physical motion is disturbingly arrested.

Disciplining my eyes to sprint like an athlete away from male classmates’ biceps or smiles, somehow my eyes landed on Dickinson’s poems. Poem after poem lamented constraints around male bodies, and poetry’s muscles got them moving again.

Most scholars regard Dickinson as the champion of women, whose work busts boundaries of conventional feminine propriety. In her critiques of marriage and childrearing as women’s true calling, and in her turn to domestic labor to rethink civic life, Dickinson is one of feminism’s boldest voices.

What often gets lost is Dickinson’s relentless reimagining of masculinity. Much of Dickinson’s art surprisingly focuses on men. Her poems again and again return to men’s bodies: immobilized, trapped, confined. She reimagines them released into freewheeling openness.

Dickinson wrote during the Civil War, when American masculism trumpeted at unprecedented scales. She witnessed firsthand the ways closed ideas about masculinity preempted, rather than enhanced, the agility of male bodies. Masculism does not expand possibilities for men, but narrows them. Masculism enlists male bodies into battle, into what Dickinson calls the “horrid Bowl” that captures them into inescapable arcs of violence.

She mourns the men who do not enjoy freewheeling mobility, but who drop injured or dead. They “dropped like Flakes – / They dropped like Stars – / Like Petals from a Rose.” Delicate, irreplaceable, and beautiful bodies of sons, nephews, brothers, and husbands of Dickinson’s neighbors and friends fell into injury and annihilation. Men moved, but in horrifyingly restricted ways: they raced back and forth across battlefields, invaded territory, fought, slashed, killed, and died. Martial masculinity left little room for experimental freestyling.

Of course, there is a long distance between men wielding footballs between goal posts and men wielding bayonets in Gettysburg. But somehow there is a short distance, too, between Friday night lights and a windswept hush in Pennsylvania. Men are cheered when they immobilize other men, when they force men to submit, rather than invite them to be tender.

As men’s capacities for motion were limited to fighting, killing, and dying, Dickinson’s poetry releases them into improvisational motion. She wields language as a muscle that frees men from lockdown and invigorates them again. She drops the old story lines and raises men into intensified being.

In her poem “I rose – because He sank –,” Dickinson performs physical therapy, refusing to let a man fall into arrested development:

I sang firm – even – chants –

I helped his Film – with Hymn—

And so with Thews of Hymn –

And Sinew from within –

And ways I knew not that I knew – til then –

I lifted Him –

We all know that increased reps of weights build stronger, more resilient, and flexible bodies. So do increased reps of poetry. Men who train under Dickinson learn that tenderness is no soft and squishy practice. It takes grit, brute strength, and stamina to venture into sensitivity.

In Dickinson’s gym, men develop muscles to move with greater extension, grace, and tenderness; their bodies soften and open. Their lips part more easily, not necessarily to kiss another man’s, but to ask a difficult and unpopular but necessary question. Or they develop the stamina to hold their lips firmly shut when the urge to mansplain strikes. Their hearts become strong enough to open their lips to take responsibility for a wrongdoing, or to share a personal struggle to help someone feel less alone. Their hearts become strong enough to open their lips to take responsibility for a wrongdoing or to share a personal struggle to help someone feel less alone. Their eyes hold their gaze longer to notice a coworker’s hidden talents. Their fingers move across the keyboard to write a kind email that they send to the coworker like a baton of open-heartedness to a teammate in a relay race.

Membership at Dickinson’s gym is free. It’s open 24/7. You can join at your nearest library, or get a workout in during your next Internet search. Try it for yourself. Tell your friends.

Share your reflection