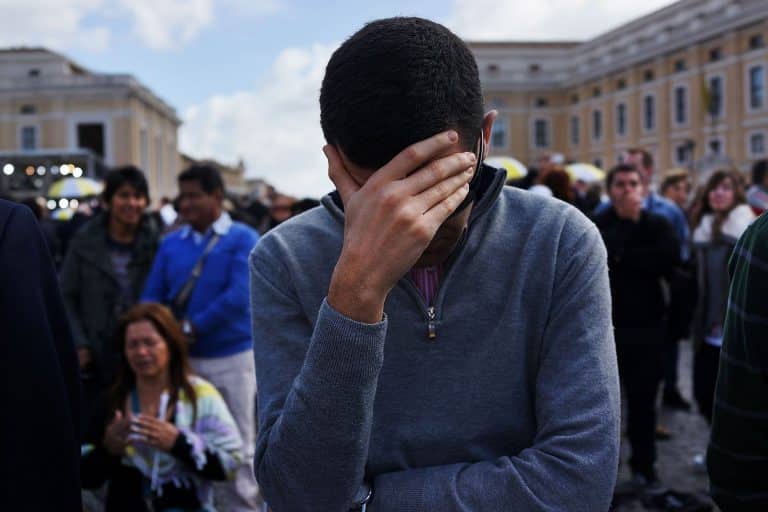

Image by BellaGaia/Flickr, Attribution-NonCommercial-Sharealike.

We Are Not Middle Aged: What Medieval Women Taught Me About My 40s

It starts happening before you realize it and by the time you do, the slow, grinding erasures have already begun. At church, the young adult group gets mentioned repeatedly, and even though you look around and realize you’re one of the youngest people there, you’ve crossed the mysterious river into your forties. You’re suddenly too old for the young adult group. You’re also very frequently alone in church. Generation X lost interest in Christianity around the time of Reagan’s “shining city on a hill” and Tammy Faye Bakker’s smeared mascara, and only one of your fellow born-in-1971 (which wasn’t that long ago) friends takes Christianity very seriously, and she’s a priest, so, it’s her job. Yet here you are, still trying.

You’re too young for the “50 and over celebration of life!” at church, but too old for the “baseball and beer and Jesus” excursion with a firmly underlined reminder that “anyone under 40 is welcome.” You’re too old to be on social media but too young to quit. Too old to wear those jeans but too young for those other jeans. Too old to have so many tattoos but too young to stop getting them.

A younger friend says you look “good for your age,” but you’re not sure what that means when you watch Big Little Lies and realize Nicole Kidman, four years your senior, has perfectly undisturbed, luminescent skin, like the shimmering surface of a faraway planet, while your own skin is forked and pitted. You look for other TV shows, movies, or books about women in their forties, and in each of them, the woman is screaming, crying, throwing her phone, frowning in dressing rooms, getting divorced, getting cancer, fighting with her children, fighting with her parents, or embarrassing herself repeatedly, every single day. She is, in a word, messy.

A year or so ago I sat across from my spiritual director, a sweet Franciscan somewhere in his 60s, rattling off this same series of complaints. I felt messy, every day. He asked exactly how old I was. When I said I’d just turned 45, he sighed. “That’s a hard age,” he told me. Something shifted inside. I’d been rolling the Sisyphean boulder of my age since I turned 40, just waiting for things to get easier, as older women kept reassuring me they would. Apparently at some point I would reach a magical age when I had “no f*cks left to give.” But no one had warned me that before I hit that magical age, I’d have to survive my forties.

And in my forties, I had many f*cks left to give. I gave so many f*cks that it still hurt like hell when a book proposal got rejected, when four older friends died within the space of a few months of one another, when I got mansplained on panels or trolled on social media, when I started showing the first signs of perimenopause or stopped getting complimented on my (still stylish, not at all matronly) clothes or developed chronic knee pain. “But I was supposed to start transcending that stuff!” I wailed to my older sisters, both in their early fifties.

They told me it might take a while.

Numerically, I am middle-aged. But I resist that term, not because of its unfriendly reminder that I’ve hit some Dante-esque pivot point at which I’ve become lost in a dark wood, but because I don’t know what I’m in the middle of. My writing career didn’t really begin to take off until I was nearly 40, so how can I be in the middle of it when I’m still just getting started? My father died at 52 after a car crash, but my mother is still going strong at 79, and my grandparents lived to nearly a hundred. How can any of us know we are in the middle when the end is so unclear?

The dark wood where Dante is lost is the “selva oscura”: in the Medieval imagination, questing knights were often lost and disoriented among the trees, their paths forward put on hold while they went mad due to a loss of direction, spinning around in their chaos. The Medieval era was indeed a difficult time, particularly for women who had little agency, almost no control over their bodies, and brutally short lives. But in any frightening era throughout history, or in any frightening era of our lives, there are always exceptions.

In the year 1147, Pope Eugene III read an unusual book. Titled Scivias (“know the ways”), it was written by a Benedictine nun named Hildegard. At the age of 43, Hildegard, who had been having mystical religious visions since she was three, “heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, ‘cry out therefore, and write thus!’” The pope encouraged Hildegard to keep writing, but he may not have known what he was getting into. The Scivias are, to put it mildly, a real trip: Hildegard describes the universe as an egg and salvation as a building decorated with allegorical figures, and the book ends with the Symphony of Heaven, a foreshadowing of the musical compositions that would become yet another part of her output.

Hildegard continued to write throughout her forties, but like most writers, she also held down a day job, working as the abbess of her monastery. As she moved into her fifties and sixties, Hildegard’s fevered imagination couldn’t be held in by the confines of Latin, so she invented her own alphabet, the Lingua Ignota. She also wrote about medicine and even served as a pharmacist for her community and wrote 69 musical compositions and the largest surviving collection of letters from the Medieval era. In a time when many women were confined to the home or to cloistered monasteries — and within the boundaries of the Catholic church, still closed to the ordination of women today — Hildegard embarked on preaching tours throughout Germany, calling out clerical corruption.

Roughly a hundred years later, the British mystic Julian of Norwich, who like Hildegard had been struck by a series of visions, became an anchoress attached to the Church of Saint Julian. We know almost nothing about her life before she turned 30, but a testimony by her fellow female mystic Margery Kempe, the author of the first autobiography in English, describes visiting Julian in 1414. Kempe was the mother of 14 children; Julian, as far as we know, had none. One wonders what kind of conversation these two female mystics got up to.

Anchoresses lived in a small cell attached to a church, where they dispensed counsel to pilgrims and locals. Julian’s most famous quotation from her Revelations of Divine Love, “all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well,” is now seen everywhere from cards to coffee mugs. But Julian, like Hildegard, used her confinement to push the boundaries of our understanding of God: She referred to Christ as both mother and brother, unbound by gender but capable of boundless compassion. In the Revelations, she gives us a creed most useful to women dealing with being a difficult age: “Thou shalt not be overcome.”

Hildegard, Julian, and other Medieval women religious like Clare of Assisi, Catherine of Siena, Bridget of Sweden, and Mechthild of Magdeburg stood up to church authorities by creating forms of life for their religious communities and putting their visions into words. They were paralleled by secular women like Christine de Pizan, whose Book of the City of Ladies is considered an early feminist classic. The Beguine communities were formed in the same era, where unmarried women could live independently in communities of other single women, tending to the neighborhood poor. Beguines did not take vows like women religious did, but they shared homes, ideas, and goals.

The Beguines were eventually accused of heresy by the institutional Catholic church. So were many of the female mystics, some of whom, like Hildegard, have since been re-evaluated and elevated to Doctor of the Church status. Others, like Julian, are still so controversial they are not even canonized as saints in the Catholic church. Today, we often take feminism and what it’s given us for granted, which makes it harder to understand how unusual these women were in the context of their time. But what they offer a modern woman in the midst of the years when we are feverish with change, our declining physical fertility paired with increasingly fertile minds, is a different way of thinking. What was pushed to the margins, cloistered, and silenced feels absolutely contemporary. The end of the Medieval era, after all, was the beginning of the Renaissance.

Mysticism is both the search for oneness with God and the pursuit of truth. It also exists mostly outside of the restrictive boundaries of institutional religion. There are mystics in Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism — nearly every religious tradition. And in each tradition, much like women in their forties today, mystics and women mystics in particular have historically been erased, censored, and misunderstood. We are still figuring out what “the change” really means; until her periods stop, a woman can go through a decade or more of mysterious symptoms, everything from a burning tongue to a buzzing scalp to ringing in her ears. But this is not heresy or madness. Endurance is what it takes to become prophetic.

Like many of these startling Medieval women, an increasing number of us never had children. Or among those who did, those children are becoming independent beings. So the wild swing of changes in this decade can go two ways. We can grieve what never happened or grieve moving beyond caretaking, or we can make the decision to see the decline of fecundity as the beginning of something else: a fecundity of the imagination, an era when we become not creative, but creation. Like the Medieval mystics, we are generative, even if our work is assigned to the margins as the larger culture chooses to chase youth. But change, after all, always comes from the margins. And women in their forties are still capable of change.

We are young enough remember being chased simply because we were young and old enough to be glad that’s over. We are also young enough to see when younger women are being exploited and abused and old enough to do something about it. We are young enough to understand when people are being silenced and old enough to quiet down in order to amplify the silenced. We are young enough to see the dangers of the present moment and old enough to put them into context. We are young enough to understand the Middle Ages was a time when women were confined and old enough to see how they defied confinement. So, no. We are not middle aged. We defy our confinements. And we become Medieval.

Share your reflection