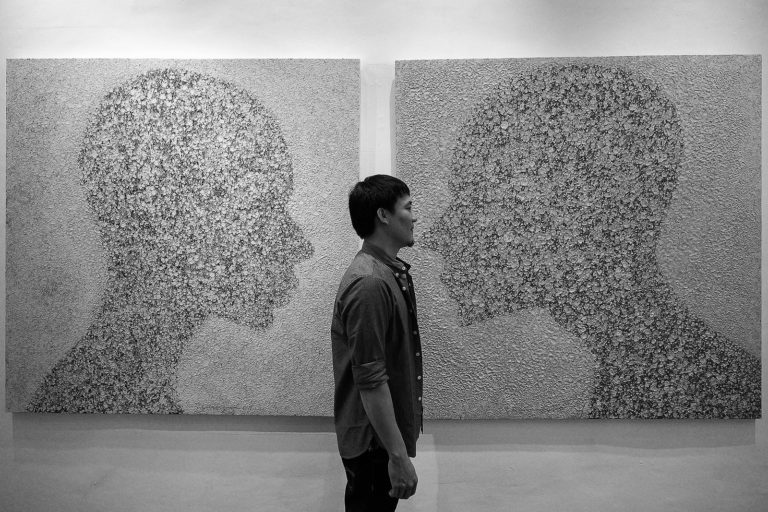

An attendee to the Republican National Convention speaks to a protester in Cleveland, Ohio. Image by Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Krista Answers a Listener’s Question About Conversation with a Trump Supporter

https://www.facebook.com/OnBeing/videos/10153814065756876/

“I spent the weekend talking to — mostly, listening to — Donald Trump supporters, and I need to talk to you about civil conversations.”

This great letter came in to us from Shani Rosenbaum in Jerusalem. It’s a situation many of us have been in this election season. Does conversation really matter, when our disagreements are so stark and important? Krista took to Facebook Live with a response that speaks to the days ahead beyond the outcome of today’s vote.

Here’s the letter she shared with us:

Dear Krista,

I spent the weekend talking to — mostly, listening to — Donald Trump supporters, and I need to talk to you about civil conversations.

I want to believe conversations matter. I want to believe it primarily, perhaps, because it’s what I’m good at. For several years I trained facilitators at Encounter to conduct constructive conversations around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Between that and investing some years in Talmud study, I’ve gotten pretty good at listening under the surface of a conversation for people’s most deeply-held values, at identifying and articulating points of conflict and points of shared concern. And I want very much for that process to matter.

Several years go, I listened to the beautiful conversation you conducted between Frances Kissling and David Gushee about abortion. I felt so inspired by it, even though I remember that someone referenced the Planned Parenthood study that is a thorn in the side of every conflict transformation junkie — the one that found that after years of dialogue, the pro-choice and pro-life activists liked each other better, but had also become more deeply entrenched in their original opinions. That was the same year you hosted a live show for Encounter with Jonathan Haidt, whose work I admire enormously; and yet I felt that Haidt himself, when pressed, didn’t have an answer to how seeking an understanding of the values at play in partisan politics could practically make significant shifts in people’s minds or hearts.

Yesterday, my Israeli roommate invited me to a party hosted by a a die-hard American conservative friend. She wanted me to talk to a crowd of Trump enthusiasts about why I was voting for Hillary. I told her that if they were truly fans of Mr. Trump, shared his values and his vision, then I wouldn’t be able to convince anyone of anything. But I went, because it’s important for me not to preach against closing ourselves off in echo chambers without occasionally emerging from my own.

It wasn’t long before a young man took me aside and suggested that I simply hate Donald Trump because he had said “this and that about women.” I told him I was concerned both about the jokes he had made and several accusations of actual sexual assault that have been brought against him. My new friend told me I was taking those too seriously, and I asked him what makes him feel the accusations aren’t worth being taken seriously. He said “I’m a man, and I understand powerful men, and they don’t need to rape.” We then had an illuminating, but sadly unsurprising, conversation about what constitutes consent in a sexual encounter. We disagreed — civilly — about whether, if a woman has come over to a man’s house late at night and then changed her mind and said no to sex, this would be considered rape. He was surprised to learn that if, for example, he and I were in the middle of sex and I asked him to stop and he did not, I would also consider that rape.

I do not feel this man and I were holding equally valid, parallel narratives of the way to world works. He is wrong, his wrongness is dangerous, and though we weren’t shouting past each other, we were speaking in such very different languages, had such contrasting frameworks for thinking about so many fundamentals of living, that there was at the outset of that conversation virtually no chance either of us would leave truly affected by the other.

What’s frightening to me is I feel like I understand Trump supporters. I understand them because they are every boy in my high school. I spent years listening to those boys, and they are now the ones on my Facebook feed saying exactly what I expect them to say about the presidential race. I am afraid, because my training brings me to the edge of the vast gap between me and Trump’s America — I can point to the chasm, name it, articulate its origins, but lack the tools to bridge or close it.

I want to believe, deeply, in your work, because it is the kind of work I want to do in the world. The conversations you engage in on your show are moving; they offer me new and rich language for living. But I imagine — am I wrong? — that your listeners are mostly my peers. We employ an exclusive vocabulary and have formed, if unintentionally, our own echo chamber around it. I suggest this not to be mean or accusatory, but to ask how you live with that concern, how you begin to answer that question when you ask it of yourself.

When I speak to Israelis and Palestinians about the conflict here, I tend to shy away from asking about hope. I ask, instead, what gets them up in the morning; what are they reaching towards, or what’s pushing them forward, when hope feels ridiculous? I want to ask you if you believe in conversations. Do you? And from where do you draw that faith?

With blessings and thanks,

Shani Rosenbaum

Jerusalem

Here is a transcript of Krista’s response:

So again, this is a wonderful letter. It came into my inbox, I read it and knew it was terrific. I read it very quickly before we pushed the “on” button this morning. And I just made a couple of notes as I would do in the moment in a conversation. And I just want to talk through my responses for a couple of minutes and honor these questions that Shani has posed of me — and I really think of us — of our common life as we move forward beyond this election.

So the first thing I want to say is resoundingly, yes, I do believe in conversation. And I don’t believe in conversation for the sake of conversation, but it’s been very much a core faith behind this entire project in all its years, that the point of speaking together differently is learning to live together differently.

But what I want to say also, and I think is revealed in this, and is revealed right now, as a lot of us have similar encounters and similar concerns, is that we have to create entirely new ways to begin to speak to each other, new framings. We have to create new kinds of spaces that don’t have the same kinds of assumptions even about why we’re in the room together. So I think that creating an event where, you’re invited to tell people who are already on the other side of an issue that is defined that is a yes or no, up or down, are you voting for Trump, are you voting for Hillary Clinton. I think already the chance of having any kind of different conversation or emerging from that with a different kind of relationship is very limited.

I also think that we tend to go into these spaces with some of the assumptions that are part of our political life, like the idea that we have to come out of any single encounter with some kind of resolution, with some kind of result. You’ve convinced them or you haven’t, you’ve joined forces or you haven’t. I actually think even in the midst of — even in the thick of this, you know, when Shani says, “We then had an illuminating, but sadly unsurprising conversation. We disagreed civilly.” There is actually some progress in there that you can point at.

But more importantly, we set ourselves up to feel like we are failing when we create spaces where the resolution is simply not going to happen and where we don’t take a long view, a realistic view of how long it took all of us to back ourselves into these corners we’re in or to develop these positions we have. And how long it would take us not necessarily to convince each other, you know, for one person to come out saying they were wrong and the other person to be vindicated, but to come into relationship with each other, to be able to know the questions to formulate that would actually draw out the other person and allow us to know them in a new way.

The third thing I would say about what goes wrong in the way we set up spaces, but that’s very instinctive, is that we think — and this is where we’re modeling, we’re taking the model of, again of political discourse and of media discourse, that the people we have to convince for anything to make a difference are those people who are absolutely on the other side of the spectrum on us, the people with the hardest positions, the people who, at least on the surface, have absolutely no questions alongside their answers. And we have this illusion that we can’t convince those people that our agency in common life is very small and limited. We get paralyzed and we get depressed and demoralized.

I really believe that though we set up these competing poles to frame our important challenges, most of us left to right, left of center and right of center, have some questions left alongside our answers. And yet, again, the way we are just trained, just the muscle memory we have is that we have to set up spaces that are about competing certainties. And again it is predetermined if that’s the way we’re setting up a space, very limited what can possibly come of that. I do also want to say that Shani’s challenge is correct that that doesn’t mean we get to just be in the spaces we’re comfortable in.

We do inhabit a world in which it’s easy to live in bubbles. So when I talk about creating a space, a conversational space, a human space in which a different kind of conversation can happen that does mean that we have to be really willing and eager to step outside our comfort zone, to ask searchingly why people are not in the room who need to be there for this to be more than a conversation among ourselves, more than preaching to the choir. I consider this to be work of hospitality.

And I actually think although, because we do inhabit these worlds where we are so segregated in so many ways along lines of opinion and generation as along the lines of politics and socioeconomics and race. It’s hard automatically to know how to invite people on the other side, whatever that other side is, but it’s not rocket science. It means that we have to have some conversations among ourselves that we don’t have that often. Think about the six degrees of separation. Get some people you know together, who again are your choir, but ask each other and yourself, who do I know?

Maybe it’s a friend of a friend, maybe it’s your brother-in-law, maybe it’s somebody who wrote an op-ed for your local paper and you didn’t agree with what they said. They were clearly on the other side, again whatever the other side is, but you could tell they were really smart and you could tell that that would be an interesting and valuable person to be in conversation with and invite those people. So, yes, we do have to — that’s also part of — challenging ourselves is part of creating those spaces.

Now, I feel like I’m going on long time for Facebook Live, that this is too long. I want to come back to the questions that Shani noted that are wonderful. So we have the different kinds of hospitality in terms of who we’re inviting, what the invitation is, what we think can and can’t happen in that space.

One other thing I’d add about the point of having a conversation that seems to fail, that seems not to change anything, and you don’t think you’ve gotten through is that actually one thing we know from brain science and that we get to hang on to is that people who feel they’ve been heard, even if they end up on the losing side of whatever the event or the debate is, ultimately are better able to gracefully accept the result of what happened, again even if they are on the losing side. It’s not something that’s going to turn up in the moment. It’s not something you’re going to see at the end of the hour. But it also speaks I think to the value of believing in conversations, believing in the power of the conversation and doing it even without the kind of immediate rewards and proof of the product that we’re used to insisting on in our culture.

So Shani asked these questions at the end. I think this is valuable for all of us. She says, “When I speak to Israelis and Palestinians about the conflict here I tend to shy away from asking about hope. I ask instead, what gets them up in the morning, what are they reaching towards, or what’s pushing them forward when hope feels ridiculous.” Those are fantastic questions. So those are tools. Those are pieces of intelligence for common life, for creating not just conversations but relationships, which is the point of this, the idea that even if we continue to disagree on things we have a sense and we have some foundation for living together.

I would add to those great questions that Shani offers up — I always think about — she mentioned that conversation with Frances Kissling and David Gushee and I think about some tools, some questions as tools that Frances Kissling offered up that a lot of people have told me are valuable, that I found valuable. Can you get to a place in your conversation with different others — and you do have to get to this place this is not the first conversation. This is going to be down the road a bit when you’ve established some trustworthiness, some safety. Can you get to the place where you could ask of yourself and openly discuss what makes you uncomfortable where do you have some doubts about your position or your group? And the other question would be, what do you find to admire in the position of the other. That’s an absolutely unimaginable set of questions and genuine responses for us in our political life. But I’ve seen that happen when those questions are asked and probed together. It is life giving and transformative on a level that I think much more profound than the level of positions changed in the moment.

I think I also wanted to say finally that, again, we are so wired and we’ve trained ourselves, all our muscle memory goes towards debating our answers, debating our certainties, and that’s one form we need to grapple with complicated challenges, but these human, civilizational, social, spiritual crises that are now so on the surface of our life. They’re not going to have answers. They may never have certainties. Our questions matter too. Our questions matter in the quality of conversation we can create. They matter in our grappling.

And I think that another way that we could think about and practice coming together with people on the other side is if we came together and tried to define some shared questions that we share even amidst whatever is dividing us and whatever makes us different from each other. And if you’ve read me or you’ve listened to the show you’ve probably heard me quote Rilke talking about loving questions, living the questions — loving questions like they are locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language and that you shouldn’t look for the answers that you couldn’t live, but the point is to live the questions so one day you may live into the answers.

I think one of the reasons our public life feels so fraught and frightening right now is that it is defined in many ways by these vast open questions that aren’t going to have resolution, but part of the question about not just whether we can live together peaceably and creatively, but whether we can grow up as a species is if we can take on that work of living those questions.

So that’s me for my first venture in Facebook Live. It’s a beautiful day here on Loring Park and I hope you have a wonderful day wherever you are.

And — spoiler alert — after we posted Krista’s response, Shani shared it with the man who sparked her letter as a jumping-off point for their next conversation. They’re getting drinks next week.

Share your reflection