Image by Nur Lan/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)..

Let the Discomfort Begin with Me

A monumental transformation is occurring. In this country and across the globe, people increasingly have an alternative to withering in old age homes and dying in hospitals — and millions of them are seizing the opportunity. But this is an unsettled time. We’ve begun rejecting the institutionalized version of aging and death, but we’ve not yet established our new norm. We’re caught in a transitional phase. However miserable the old system has been, we are all experts at it. We know the dance moves. You agree to become a patient, and I, the clinician, agree to try to fix you, whatever the improbability, the misery, the damage, or the cost. With this new way, in which we together try to figure out how to face mortality and preserve the fiber of a meaningful life, with its loyalties and individuality, we are plodding novices. We are going through a societal learning curve, one person at a time. And that would include me, whether as a doctor or as simply a human being.

I’ve just finished Atul Gawande’s beautiful book, Being Mortal, from which this excerpt is taken. Gawande is a humble doctor and a gifted writer; I would argue that he is one of the most important thought leaders of our time. If you haven’t been reading his work, now is the time to start.

This latest book is focused on a topic that I’ve been obsessed with ever since my grandmother died in hospice care: aging and the dying process. The thrust of his argument is that we have — for far too long — structured the last years of our lives around safety rather than meaning. We try to protect our parents and grandparents, and in so doing, very often steal their last earthly chance to express who they are fully, to love what the “soft animal of their bodies love” (to paraphrase poet Mary Oliver), to revel in the sensual pleasures of being alive. This bite of warm sourdough bread. This scent of freshly cut fir tree. This pudgy grandchild’s hand. In the very end, it is the smallest things that anchor us to the earth and our gratitude for our finite time here.

There is grounded inspiration to be found in the transition that Atul Gawande describes in Being Mortal. As a society, we really are fighting back against our own fearful, costly instincts to keep people alive, to institutionalize and coddle them. We really are creating alternatives — places where people, even very sick and disabled people, can revel in their own idiosyncratic take on the “good life,” whether that’s reading trashy magazines and watching reality shows, playing poker and drinking whiskey, taking walks in nature alone. People are having the hard conversations with more courage and clarity about the end of life experiences that they wish to have — each one as nuanced as the human being doing the wishing.

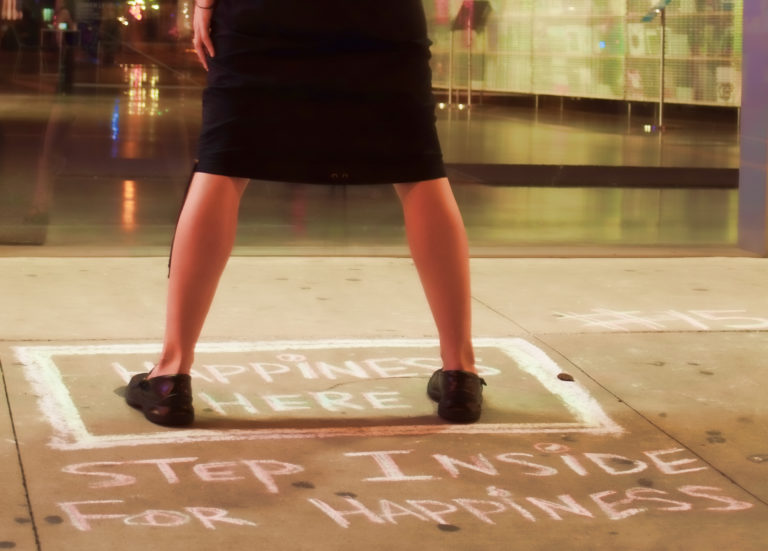

I was so struck by the passage above because it describes change in a way that transcends the topic at hand. When we have done things one way and we are straining to do them a new way, there is this hugely important liminal moment. We have to turn off auto-pilot. We have to really witness our own instincts. We have to be willing to be uncomfortable enough to do it a new way, knowing we might be clumsy at first. This is true when an entire healthcare system, and all those that interact with it, tries to deal with death differently. It’s also true when one human being decides to drink less or be more social or try a new career.

One of the prayers that I say to myself every day is this:

May I see what I do. May I do it differently. May I make this a way of life.

I learned it from an old mentor of mine named Karen. She had a pixie haircut and a strong, small body. I went to visit her at her home around Rhinebeck, New York when I was in my early 20s. She ate miso soup for breakfast and made me promise I would spend at least 20 minutes of each day in the peak sun instead of head down at my laptop (Vitamin D!). She let me borrow a book about the 60s revolts that I never returned. She taught me how to massage my own ears and do metta meditation. She died of breast cancer, but her lessons live on in me every single day.

I say this prayer, not just because she was so wise and it helps me remember her. I say it because I get bored of myself. I say it because I’m a creature of habit, like almost everybody else. I say it because I know that the “moral arc of the universe,” in King’s words, will only bend when we interrogate our own automatic thoughts and become fiercely awake about our own actions.

Gawande, a veteran clinician, describes being nervous as he tries to have more direct conversations about death with his patients. He wants to do it, and yet, it feels so unintuitive. He’d rather focus on the likelihood of their survival. But he pushes himself to do it differently. He asks the hard questions. He makes himself and his patients temporarily uncomfortable, so that they can all make profound meaning in the end.

I’m awed by a master’s bravery to be a beginner again. It seems to me to be the missing ingredient to so many movements for dignity. Let the discomfort begin with me.

Share your reflection