John O’Donohue

The Inner Landscape of Beauty

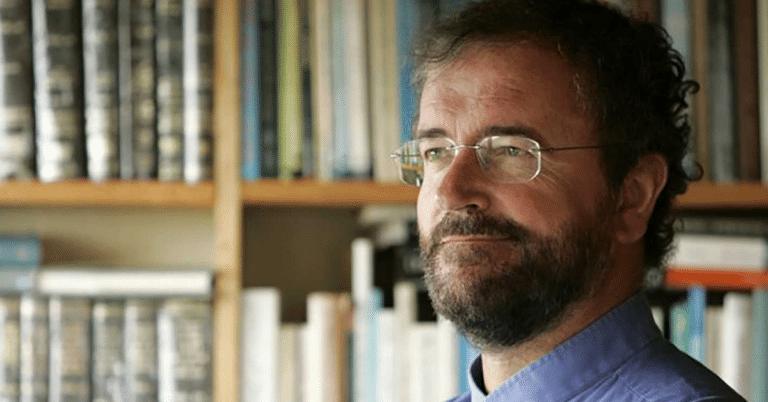

No conversation we’ve ever done has been more beloved than this one. The Irish poet, theologian, and philosopher insisted on beauty as a human calling. He had a very Celtic, lifelong fascination with the inner landscape of our lives and with what he called “the invisible world” that is constantly intertwining what we can know and see. This was one of the last interviews he gave before his unexpected death in 2008. But John O’Donohue’s voice and writings continue to bring ancient mystical wisdom to modern confusions and longings.

Guest

John O'Donohue was a poet, theologian, and philosopher. He authored beloved books, including Anam Ċara and Beauty: The Invisible Embrace. To Bless the Space Between Us, a collection of blessings, was published posthumously. A wonderful book drawn from his voice in conversation, Walking in Wonder: Eternal Wisdom for a Modern World, was published in November 2018.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zöe Keating]

John O’Donohue: Beauty isn’t all about just nice loveliness, like. Beauty is about more rounded, substantial becoming. So I think beauty in that sense is about an emerging fullness, a greater sense of grace and elegance, a deeper sense of depth, and also a kind of homecoming for the enriched memory of your unfolding life.

Krista Tippett, host: No conversation I’ve ever had has been more beloved than this one with the Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue. He insisted on beauty as a human calling. He had a very Celtic, lifelong fascination with the inner human landscape and what he called “the invisible world” constantly intertwining with what we can know and see. This was one of the last interviews he gave before his unexpected death in 2008, but John O’Donohue’s voice and writings continue to bring ancient mystical wisdom to modern confusions and longings.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zöe Keating]

Anam Ċara was published in 1997, and it became an international bestseller. John O’Donohue’s final work was To Bless the Space Between Us, published posthumously. He was born in 1956 in County Clare in western Ireland. Historically, this part of the world was a crucible of Celtic Christianity, merging a strong sense of mystery with a passionate embrace of nature, the body, and the senses. The divine is understood as manifest everywhere, in everything.

John O’Donohue entered seminary at a young age and was a Catholic priest for 19 years. But in the 1980s, he went to Germany to study the philosophy of Hegel. He eventually left the priesthood and devoted himself full-time to meditating and writing on beauty, friendship, and how the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual, intertwine in human experience.

Tell me a little bit more about where you come from and what formed you. What began to form you to come to this spiritual perspective and philosophical and poetic perspective that you have now?

John O’Donohue: Well, I suppose I was blessed by being born into an amazing landscape in the west of Ireland. And it’s the Burren region, which is limestone. And it’s a bare limestone landscape. And I often think that the forms of the limestone are so abstract and aesthetic, and it is as if they were all laid down by some wild, surrealistic kind of deity. So soon, being a child and coming out into that, it was waiting, like a huge, wild invitation to extend your imagination. And then it’s right on the edge of the ocean, as well, so the conversation — an ancient conversation between the ocean and the stone going on.

Tippett: I know that “landscape” is a really pivotal word for you that you use, not just in describing the natural world, but an important word in talking about how human beings know themselves and move through the world. I haven’t been to precisely the place you’re from, but I think the west coast of Scotland, the west coast of Ireland, it is this completely unusual, this wild, raw, bleak beauty. But talk to me about how you have come to understand landscape as something that forms each of us.

O’Donohue: Well, I think it makes a huge difference, when you wake in the morning and come out of your house, whether you believe you’re walking into dead geographical location, which is used to get to a destination, or whether you’re emerging out into a landscape that is just as much if not more alive as you, but in a totally different form, and if you go towards it with an open heart and a real, watchful reverence, that you will be absolutely amazed at what it will reveal to you.

And I think that that was one of the recognitions of the Celtic imagination — that landscape wasn’t just matter, but that it was actually alive. What amazes me about landscape, landscape recalls you into a mindful mode of stillness, solitude, and silence, where you can truly receive time.

Tippett: Are you just talking, though, about landscape as the natural world around us? I’ll tell you, I remember a summer I spent a few years after I had first gone to this beautiful, raw, wild edge of Scotland, and I was working with children in a very impoverished, inner-city neighborhood. And I would often wish that I could just transport them for an hour so that what they saw when they opened their eyes and looked around them was that kind of beauty that opens so much possibility. So I wonder how this Celtic sensibility would also speak to people who don’t have that kind of beauty at hand — that kind of beauty.

O’Donohue: I do agree with you that an awful lot of urban planning, particularly in poor areas, has doubly impoverished the poor by the ugliness which surrounds them. And it’s understandable that it’s so difficult to reach and sustain gentleness there. And I do think — like a friend of mine just in the last week, who was absolutely exhausted in London, just came away down to southern England and spent the week by the slow ocean. And she’s totally recovered. She’s come back to herself.

But I do think, though, that it’s not just a matter of the outer presence of the landscape. I mean, the dawn goes up and the twilight comes, even in the most roughest inner-city place. And I think that connecting to the elemental can be a way of coming into rhythm with the universe. And I do think that there is a way in which the outer presence, even through memory or imagination, can be brought inward as a sustaining thing.

I mean, I think that — and it’s the question of beauty, I mean, you’re asking, essentially — as we are speaking, that there are individuals holding out on frontlines, holding the humane tissue alive in areas of ultimate barbarity, where things are visible that the human eye should never see. And they’re able to sustain it because there is in them some kind of sense of beauty that knows the horizon that we are really called to in some way.

I love Pascal’s phrase that you should always keep something beautiful in your mind. And I have often — like in times when it’s been really difficult for me, if you can keep some kind of little contour that you can glimpse sideways at, now and again, you can endure great bleakness.

Tippett: I’ve been looking back at the thought of the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, and he has this statement at the beginning of his book The Nature and Destiny of Man, the first line: “Man is his own most vexing problem.” Or I think of a great, pivotal work in this culture of modern psychology, M. Scott Peck’s book which begins, “Life is difficult.” And then I read this line, which begins your book Anam Ċara, which is also a different way of kind of analyzing the human condition: “It’s strange to be here. The mystery never leaves you.” Talk to me about that as a way of thinking about what it means to be human, and how you come to that, and what you mean when you write those words.

O’Donohue: I mean, when you think about language and you think about consciousness, it’s just incredible to think that we can make any sounds that can reach over across to each other at all, because, I mean, I think we’re — I think the beauty of being human is that we are incredibly, intimately near each other, we know about each other, but yet we do not know or never can know what it’s like inside another person. And it’s amazing, you know? Here am I, sitting in front of you now, looking at your face, you’re looking at mine, and yet neither of us have ever seen our own faces, and that in some way, thought is the face that we put on the meaning that we feel and that we struggle with, and that the world is always larger and more intense and stranger than our best thought will ever reach. And that’s the mystery of poetry, is poetry tries to draw alongside the mystery as it’s emerging and somehow bring it into presence and into birth.

Tippett: What do you mean when you write that everyone is an artist?

O’Donohue: I mean that everyone is involved, whether they like it or not, in the construction of their world. So it’s never as given as it actually looks; you’re always shaping it and building it. And I feel that from that perspective, that each of us is an artist.

Secondly, I believe that everyone has imagination, that no matter how mature and adult and sophisticated a person might seem, that person is still essentially an ex-baby. And as children, we all lived in an imaginal world. When you’d be told, Don’t cross that wall, because there’s monsters over there — my God, the world you would create on the other side of the wall. And when you’d ask questions like, Why is the sky blue?, or Where does God live?, or — you know, all this kind of stuff.

Like one of the first times I was coming to America, I said to my little niece, who was seven, I said, What will I bring you from America? And she said, Uh … And her father said, No, ask him, or you won’t get anything. And Katy turned to me and said, What’s in it? [laughs] — which I thought was a great question about America. So, that childlike thing.

And secondly, that every night, when we sleep, we dream. And a dream is a sophisticated, imaginative text full of figures and drama that we send to ourselves. So I believe that deep in the heart of each of us, there is this imagining, imaginal capacity that we have, so that we are all doing it.

Tippett: And as I read you, I think what you’re also saying is that just the act of living — of creating our lives, of growing, moving forward in time — is a creative act …

O’Donohue: Absolutely, it is a creative act, because —

Tippett: … that it is a work of art to elevate, to ennoble — to give ennobling words to something we’re doing.

O’Donohue: That’s right, because the amazing thing about us — I mean, we are so strange, and we lose sight, actually, of how strange we are. I mean, I’m always amazed that you never meet a human — you meet humans looking for all kinds of things, and you never meet a human and you say to them, What are you looking for? And they say, I’m looking for yesterday; where did yesterday go to? We just take it that it goes into nothingness. And that’s on one side. The other thing, of course, is that we have no idea what will land on the shoreline of morning tomorrow, so that we are always actively involved in receiving and shaping.

Tippett: You wrote, about time, “Possibility is the secret heart of time. On its outer surface, time is vulnerable to transience. … In its deeper heart, time is transfiguration.” I wonder how you are able to have, I don’t know, I think a larger sense of time, because of — as an inheritor of the Celtic tradition.

O’Donohue: I think that’s a bit of it, that old Celtic thing, because I mean, there is, in Ireland, still, even though it’s getting consumerized so fast, there is still, in the west of Ireland where I live, a sense of time; that there’s time for things, and that when God made time, he made plenty of it, and all the rest of it. And, you see, I think that one of the huge difficulties in modern life is the way time has become the enemy.

Tippett: Time is a bully. We are captive to it.

O’Donohue: Totally, and I’d say seven out of every ten people who turn up in a doctor’s surgery are suffering from something stress-related. Now, there are big psychological tomes written on stress, but for me, philosophically, stress is a perverted relationship to time, so that rather than being a subject of your own time, you have become its target and victim, and time has become routine. So at the end of the day, you probably haven’t had a true moment for yourself, to relax in and to just be.

Meister Eckhart, whom I love, said, So many people come to me asking how I should pray, how I should think, what I should do; and the whole time, they neglect the most important question, which is, how should I be? And I think when you slow it down, then you find your rhythm. And when you come into rhythm, then you come into a different kind of time, because you know the way, in this country, there’s all the different zones? I think there are these zones within us, as well. There’s surface time, which is really rapid-fire, Ferrari time.

Tippett: And over-structured.

O’Donohue: Yeah, over-structured, like, and stolen from you, thieved all the time. And then if you slip down — like Dan Siegel, my friend, has this lovely meditation: you imagine the surface of the ocean is all restless, and then you slip down deep below the surface, where it’s still and where things move slower.

Tippett: So I’m assuming you would suggest that people need to create more space and stillness, but I think what you’re also saying is that simply by thinking differently about time, by approaching it differently, by putting on a new imagination, we can have a different sense of it. Is that right?

O’Donohue: That’s absolutely right, because I think that if you take time not as calendar product but as actually the parent or mother of presence, then you see that, in the world of spirit, time behaves differently, actually.

I mean, when I used to be a priest, it was an amazing thing — you’d see somebody who would be dying over a week, maybe, and had lived maybe a hard life where they were knuckled into themselves; where they were hard and tight and unyielding, and everything had to earn its way to their center. And suddenly, then, you’d see that within three or four days, you’d see them loosen. And you’d see a kind of buried beauty that they’d never allowed themselves to enjoy about themselves surface and bring a radiance to their face and spirit.

Tippett: And why did it surface then?

O’Donohue: Because suddenly, like, there was a recognition that the time was over and that their way of being could no longer help them with this, and that another way of being was being invited from them. And when they yielded to it, it would become transformative. And it just means that, actually, when you change time levels, that something can transform incredibly quickly.

I mean, I always think that that’s the secret of change: that there are huge gestations and fermentations going on in us that we are not even aware of; and then sometimes, when we come to a threshold, crossing over, which we need to become different, that we’ll be able to be different, because secret work has been done in us of which we’ve had no inkling.

Tippett: And where did that work come from? Who directed that work? What is that?

O’Donohue: My suspicion would be — I can’t say who directed that work. But my suspicion is that the soul choreographs one’s biography and one’s destiny. I’ll put it this way to you. Like in Ireland, there’s an indirectness — I think it was Freud or Jung said the Irish were un-psychoanalyzable, [laughs] because there’s all this indirectness. It all comes from our colonial background, because you wouldn’t say too much, because you could be caught out. And if you’d say to somebody, How are you? they’d say, Oh, not too bad. And I was always amazed, when I came to the land of the free and the home of the exceptionally brave, that if I put too much sincerity into the question, How are you?, I could have unleashed a biography in seconds [laughs] and that you’d get information that you’d never dream of.

And it often seems to me, here, that a person believes that if they tell you their story, that that’s who they are. And sometimes these stories are constructed of the most banal, secondhand, psychological and spiritual cliché, and you look at a beautiful, interesting face telling a story that you know doesn’t hold a candle to the life that’s secretly in there. So what I think happens here a bit is that there’s a reduction of identity to biography. And they’re not the same thing. I think biography unfolds identity and makes it visible and puts the mirror of it out there, but I think identity is a more complex thing.

And what I love in this regard is my old friend Meister Eckhart, the 14th-century mystic —

Tippett: Right, German mystic.

O’Donohue: German mystic. And one day I read in him, and he said, “There is a place in the soul that neither time nor space nor no created thing can touch.” And I really thought that was amazing. And if you cash it out, what it means is that your identity is not equivalent to your biography, and that there is a place in you where you have never been wounded, where there is still a sureness in you, where there’s a seamlessness in you, and where there is a confidence and tranquility in you. And I think the intention of prayer and spirituality and love is, now and again, to visit that inner kind of sanctuary.

[music: “The Bright Lady” by Declan Masterson]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, the inner landscape of beauty, with the late Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue.

[music: “The Bright Lady” by Declan Masterson]

I think a lot about how, in Western culture and in the United States culture, really important words get watered down and almost ruined, and yet we still need them. And “love” is one of those words. And “friendship,” I think, may also be a word which we haven’t — we struggle to not let our definition of that become impoverished. And just to bring this to a very practical level, some of the things we wring our hands about in our public life — like the disintegration of marriages, crisis of relationship; and then implications of that, like how do we raise our children to know what commitment is — and I actually think an impoverished sense of love and of friendship complicates that. I’m asking you this as a philosopher and, I think, as a wise person; I mean, are we less capable of love and commitment and relationship, in a mature sense, in our time than previous generations were? Or is this just a human dilemma that has different details in our time?

O’Donohue: That’s a very interesting question. I don’t think we’re less capable at all. I think we’re more unpracticed at it, and therefore, more desperate for it. And I think it’s a matter of attention, really, just attention — that if you realize how vital to your whole spirit and being and character and mind and health friendship actually is, you will take time for it. And the trouble is, though, for so many of us, is that we have to be in trouble before we remember what’s essential. And sometimes it’s one of the lonelinesses of humans is that you hold on desperately to things that make you miserable and that sometimes you only realize what you have when you’re almost about to lose it. So I think it would be great to step back a little from one’s life and see around one, who are those that hold me dear, that truly see me, and those that I need?, and to be able to go to them in a different way, because the amazing thing about humans is we have immense capacity to reawaken in each other the profound ability to be with each other and to be intimate.

That’s one of the things I’ve always thought, here, is that there is a loneliness here that is covered over by this fake language of intimacy that you meet everywhere and that doesn’t have — everybody will say, “Have a nice day,” to you. And you can imagine if you turn back to them and say, “God, I really wonder if I’ll have a nice day or what the day will be like,” things can get complicated, very suddenly.

And I think this is one of the key things in parenting, and the difficulty of raising children in a very, very fast-moving culture: that, again, it’s the difficulty of creating a space where children can actually unfold and where they can be truly accompanied in their journey, because I think young kids now in adolescence are going through huge, huge question zones that, when we were young, we didn’t go through. And sometimes it’s very lonesome to watch how distant parents feel from them, because of their incapacity to somehow hold conversations with them that really need to happen.

Tippett: I think something else that’s connected to all of this that we’re not very self-aware about in this culture is the connection between our interior lives and our exterior appearance — not just physical appearance, but how we conduct our lives in the light of expectations. I think that is something that you write about, again, that we just aren’t attentive towards.

O’Donohue: I feel like in the book I wrote on beauty, I was trying to say that one of the huge confusions in our times is to mistake glamour for beauty. And we do live in a culture which is very addicted to the image. And I think that there is always an uncanny symmetry between the way you are inward with yourself and the way you are outward. And I feel that there is an evacuation of interiority going on in our times and that we need to draw back inside ourselves and that we’ll find immense resources there.

Tippett: When you say “symmetry,” I don’t think you mean that there’s an equality, but that they are intimately connected and that when we are putting our energy outward, it’s taking something from inside us.

O’Donohue: It’s taking something; exactly. That’s exactly what I mean, that it’s taking something from inside, and we’re secretly debilitating ourselves. And it’s understandable, too, because if you look at the educational system and you look at most of the public fora in our culture, there is very little time or attention given to what you could almost call learning the art of inwardness; or a pedagogy of interiority. That’s why I find the aesthetic things, like poetry, fiction, good film, theater, drama, dance, and music, actually awaken that inside you and remind you that there is a huge interiority within you.

Like, for instance, when I came into New York last Thursday evening and checked into the hotel, I found out that there was a Tchaikovsky concert on in the Lincoln Center. And I went over there, and I got a ticket, one of the last tickets, which was two rows from the front, and I’ve never been so near an orchestra, and I said, my God, I’m too near, and then I watched them, and all the rest of it. But I knew why I was given the ticket, then, at the end, because it was Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D, and Lorin Maazel came out to conduct it. And then this beautiful violinist, Janine Jansen, a Dutch violinist, it was her debut in New York, and she played this. It was just unbelievable. I cried. After the first movement, people spontaneously stood up and wanted to give her a standing ovation, and she just held it, and we all went back again into our seats. And then at the end, people were just blown away, because an event, an aesthetic event had happened.

This is a complicated piece of music. Everywhere — she was playing a Stradivarius from 1727 — everywhere she went on this violin, she got exactly what she was looking for. She held it; and Maazel was so sovereign and so — like a huge patriarch. And three or four times — I was up close enough to see them — he looked at her with the wistful, proud gentleness of a grandfather. And there was this young woman, this beautiful, slim body, and you could almost see the music hurting her, even when she wasn’t playing.

So it was a huge — everybody, and there were hardened New York critics there, but everybody was so touched. And I think that that’s the magnificence of beauty, is that even in landscapes of control, corrugated categories, that you can be swept off your feet by just beauty.

[music: “Danse Russe” from Swan Lake, by Peter Illych Tchaikovsky, performed by Janine Jansen]

Tippett: The late Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue. This is the Dutch violinist he just mentioned, Janine Jansen, playing another piece by Tchaikovsky, Swan Lake.

[music: “Danse Russe” from Swan Lake by Peter Illych Tchaikovsky, performed by Janine Jansen]

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment

[music: “Jig and Reel: The Pipe On the Hob/The Colliers’ Reel” by Dennis Cahill]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, we’re exploring the inner landscape of beauty, a notion of the late Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue. I interviewed him just before his death in 2008.

John O’Donohue often wrote about beauty. He believed that the human soul does not merely hunger for beauty, but that we feel most alive in the presence of what is beautiful. “It returns us, often in fleeting but sustaining moments,” he said, “to our highest selves.”

You also suggest, in your book about beauty, that beauty can be a kind of antidote, even to our most pressing global crises. How do you think of beauty as relevant in that sense?

O’Donohue: I think it’s not just relevant, like, but I think it’s actually necessary, because I think that beauty is not a luxury, but I think it ennobles the heart and reminds us of the infinity that is within us. I always love what Mandela said when he came out — and I was actually in his cell in Robben Island one time, when I was in South Africa. After 27 years in confinement for a wrong you never committed, he turned himself into a huge priest and came out of this sentence, where he said that “[w]hat we are afraid of is not so much our limitations, but the infinite within us.” And I think that that is in everybody.

And I suppose the question that’s at the heart of all we’ve been discussing, really, which is a beautiful question, is the question of God. And I think that one of the reasons that so many people turn away from religion in our times is that the God question has died for them, because the question has been framed in such repetitive, dead language. And I think it’s the exciting question, once you awaken to the presence of God.

Tippett: Well, you have said — you write, “God is beauty.”

O’Donohue: Yeah, I have, yeah.

Tippett: Did you always feel this? Is that a sense that has grown in you, or something that you name now?

O’Donohue: It’s a sense that has grown in me, I suppose, that I’ve always kind of had the intuition about it, because I feel that there are two ways that you must always keep together in approaching the God thing. One is — and this is what I like about the Christian tradition, and this is where I diverge a little from the Buddhist tradition, even though I love Buddhism as a methodology to clean up the mind and get you into purity of presence. What I love is that at the heart of Christianity you have this idea of intimacy, which is true belonging, being seen, the ultimate home of individuation, the ultimate source of it, and the homecoming; that that’s what I’d call spirituality, is the art of homecoming. So it’s St. Augustine’s phrase, “Deus intimior intimo meo” — “God is more intimate to me than I am to myself.”

Then you go to Meister Eckhart and you get the other side of it, which you must always keep together with it, where in Middle High German he says, “Gott wirt und Gott entwirt.” That means, “God becomes and God un-becomes.” Or, translated, it means that “God” is only our name for it, and the closer we get to it, the more it ceases to be God. So then you’re on a real safari with the wildness and danger and otherness of God. And I think when you begin to get a sense of the depth that is there, then your whole heart wakens up.

I mean, I love Irenaeus’s thing from the second century, which said that “[t]he glory of God is the human being fully alive.” And I think in our culture that one of the things that we are missing is that these thresholds where we can encounter this and where we move into new change in our lives, there are no rituals to help us to recognize them or to cross them worthily.

Tippett: And “threshold” is a word you use a great deal in your book on beauty, as well.

O’Donohue: ’Tis, yeah.

Tippett: And what is that relationship between beauty and thresholds?

O’Donohue: Well, I think that the threshold, if you go back to the etymology of the word “threshold,” it comes from “threshing,” which is to separate the grain from the husk. So the threshold, in a way, is a place where you move into more critical and challenging and worthy fullness.

And I think there are huge thresholds in every life. I mean, I think that, for instance — to give a very simple example of it is that if you are in the middle of your life in a busy evening, 50 things to do, and you get a phone call that somebody that you love is suddenly dying, it takes 10 seconds to communicate that information. But when you put the phone down, you are already standing in a different world, because suddenly, everything that seemed so important before is all gone, and now you are thinking of this. So the given world that we think is there, and the solid ground we are on, is so tentative, and I think a threshold is a line which separates two territories of spirit. And I think that, very often, how we cross is the key thing.

Tippett: And where is beauty in that?

O’Donohue: Where beauty is, I think, is — beauty isn’t all about just nice loveliness, like. Beauty is about more rounded, substantial becoming. And I think when we cross a new threshold, that if we cross worthily, what we do is we heal the patterns of repetition that were in us that had us caught somewhere. And in our crossing, then, we cross onto new ground where we just don’t repeat what we’ve been through in the last place we were. So I think beauty in that sense is about an emerging fullness, a greater sense of grace and elegance, a deeper sense of depth, and also a kind of homecoming for the enriched memory of your unfolding life.

Tippett: I want to ask you — I think right when we began to talk about beauty, you rightly said that in this culture we tend to associate beauty with glamour. And I think if you just mentioned the word, if you just threw it into a commonplace conversation, someone might just think of a beautiful face, of a famous, beautiful face. And I wanted to ask you, when you think of the word “beauty,” what pictures come into your mind?

O’Donohue: When I think of the word “beauty,” some of the faces of those that I love come into my mind. When I think of beauty, I also think of beautiful landscapes that I know. Then I think of acts of such lovely kindness that have been done to me by people that cared for me in bleak, unsheltered times or when I needed to be loved and minded. I also think of those unknown people who are the real heroes for me, who you never hear about, who hold out on lines, on frontiers of awful want and awful situations and manage, somehow, to go beyond the given impoverishments and offer gifts of possibility and imagination and seeing.

I also think — always, when I think of beauty, because it’s so beautiful, for me — is I think of music. I love music. I think music is just it. I mean, I think that’s — I love poetry, as well, of course, and I think of beauty in poetry. But I always think that music is what language would love to be, if it could.

Tippett: [laughs] I have to say that I discovered Celtic music after going to that part of the world, Scotland especially. And Celtic music, for me, has this completely — you could say this about Beethoven, as well, but, in a very particular way, it seems to express the greatest joy and also the deepest sorrow, almost indistinguishable from each other, and yet both with a kind of healing force. I can’t even put words around what I —

O’Donohue: That’s beautiful, what you’ve said, though, because I think there is that. One of the things I’m always amazed about Irish music, for instance, is how in some way the lines of the landscape find their way into the music, the memory of the landscape, almost; the memory of the people too, and that in some sense, despite the sorrow that we’ve endured — and I mean, Ireland, it’s not fashionable to say it now — Ireland has hundreds of years of an awful history of suffering.

Tippett: And I feel that you hear that in the music of Ireland.

O’Donohue: You hear it in the music, you do. Even in the fast music and the light, gay music.

Tippett: Even in the celebratory — yes. Yes.

O’Donohue: Yeah, you do. Yeah, you do. You hear it there. You hear the undertones and the quiet spaces where the echo of this hauntedness comes through.

Tippett: And yet, it is absolutely linked with — see, “joy” doesn’t even do it either — with this exuberance.

O’Donohue: It doesn’t. Yeah, there’s an exuberance or a vitality. There’s some kind of vitality. And I know friends of mine who play, and when they play, they’re unreachable. You can’t find them. They’re serving the music. They’re just in another place.

[music: “Samhradh, Samhradh” by The Chieftains ]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today revisiting my conversation with the late Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue.

[music: “Samhradh, Samhradh” by The Chieftains ]

I would like to hear about the work you do in corporations and workplaces. It seems to me, in a strange way, some of the greatest intimacy and community we have, or fail to have, is with our colleagues at work. And because we spend so much time at work and it so defines us, our souls — the light and darkness of our souls is on display at work. And yet there’s a real question about how do we honor that in ourselves and in others and remain professional? I don’t know if that’s what you get at in your work with corporations, but that’s kind of on my mind.

O’Donohue: I think you’re right. I mean, we spend over one-third of our lives, actually, in the workplace. And one of the loneliest things you can find is somebody who is in the wrong kind of work; who shouldn’t be doing what they are doing but should be doing something else, and haven’t the courage to get up and leave it and make a new possibility for themselves.

But it’s lovely when you find someone at work who’s doing exactly what they dreamed they should be doing and whose work is an expression of their inner gift. And in witnessing to that gift and bringing it out, they actually provide an incredible service to us all. And I think you see that the gifts that are given to us as individuals are not for us alone, or for our own self-improvement, but they’re actually for the community and to be offered. And I think that this is where leadership comes in, in work. And that’s why I think good, wise leadership will be attuned to the vitality of a true ethos and helping to establish it.

Tippett: And are you finding that there is great interest and curiosity and willingness to have this new kind of imagination in workplaces?

O’Donohue: I really think there is, because I think in most workplaces there is huge imagination anyway, but it’s usually practical imagination that’s dedicated to productivity and looking at the bottom line. And I think, then, when they stand back a little and see that the spirit and soul dimensions are not luxury items, but are actually the very origins and sources which will enable everything to flow and unfold in a new way, that then they realize that the invisible world is a secret, hidden resource that can be released and excavated for the huge resources of spirit, guidance, for areas of ourselves that we’ve forgotten.

Tippett: In many cultures in the West, in Europe and in the United States, there are controversies about where are the boundaries between religion and politics, and that’s a complicated discussion that is quite stress-filled. But what I sense and what I’m talking about on my program, many weeks in different forms, is that there is this parallel discussion happening, that there is a spiritual aspect to human life and that that is essential.

I wonder how you would speak, to address some of the fear that arises, because I think in the American imagination, for example, those things get confused. And someone might listen to you talking about being in a board room and talking about the soul — why is that not something that we should be afraid of, or that even really has anything to do with our rules about church and state or about the line between politics and religion?

O’Donohue: I think your question is absolutely, perfectly poised, because first of all, to respond directly, I do think that there should be a fear of mixing up religion and politics and money. I love that Greek phrase, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” Now, the second thing is that, of course, it’s a huge naïveté for any organization or any group or for a culture to — and it’s actually unscholarly — to believe that a religion as the locus of the wisdom and the lived spirit experience of a people is a naïve, empty mass. It’s a huge resource. And the best minds and the most critical minds know that.

The word “soul” comes from the religious tradition and the philosophic tradition. And one of the sad things here, often, is that it’s used as a bland receptacle now, for the tired energies of psychology. But if you go back at “soul” and you look at the depth and the fire that’s in it, it’s a dangerous thing to have a soul. And I think that for parenting, for relationships, and for all the domains of our endeavor and work, to have access to a religious tradition is a huge, strengthening, critical resource, which keeps you wide awake and makes you ask yourself the hard questions. Like I’ve always thought that tradition is to the community what memory is to the individual. And if you lose your memory, and you wake up in the morning, you don’t know where you are, who you are, what ground you’re standing on. And if you lose your tradition, it’s the same thing.

Tippett: And tradition, like memory, has dark passages in it.

O’Donohue: Oh, it has huge dark passages, and I mean, I would say that within the Christian tradition there are dark zones of complete horror.

Tippett: But the weight of it is …

O’Donohue: But the weight of it. And there are also zones of great light, and immense wells of refreshment and healing. And I think it’s a critical question, always, for somebody who wants to have a mature, adult, open-ended, good-hearted, critical faith, to conduct the most vigorous and relentless conversation that you can with your own tradition.

Tippett: It was actually in your book that I first realized, and I had never thought about this, that the root — the Greek root for the word “beauty” is related to the word for “calling”; to “kalon” and “kalein.”

O’Donohue: That’s right. That’s it exactly.

Tippett: That’s fascinating.

O’Donohue: It is, actually, and it means that, actually, in the presence of beauty, it’s not a neutral thing, but it’s actually calling you. And I feel that one could write a wonderful psychology just based on the notion of being called — being called to be yourself and called to transfigure what has hardened or got wounded within you. And it’s also, of course, the heart of creativity, this calling forth all the time, because, like in the work that I do, trying to write a few poems, you never write the same poem twice. You’re always at a new place, and then you’re suddenly surprised by where you get taken to.

Tippett: But if we think, as you’ve suggested, as beauty as relevant to some of the most troubling problems in our world and in ourselves, how do we pursue that calling, given the limitations, given that a lot of what is around us is not visibly, objectively beautiful and may not be?

O’Donohue: Absolutely, and that’s a very fair question. And it’s like, in old notions of growth and development, there was always this idea — as Noel Hanlon, a poet friend of mine says in a poem about her daughter: “Like me, you needed something to push against” — that somehow we needed something to push against in order to grow. Now there’s almost a feeling like as though growth should be delivered to us. And I think that from the way you state it is that it’s a recognition that there is this dialectic there; that around us the forces are not kind, in terms of either recognizing, awakening, or encouraging beauty, but that actually, they should be the impetus and the spur to do it.

Now, how do we do it? One way — and I think this is a really lovely way, and I think it’s an interesting question to ask oneself, too. And the question is, when is the last time that you had a great conversation, a conversation which wasn’t just two intersecting monologues, which is what passes for conversation a lot in this culture? But when had you last a great conversation, in which you overheard yourself saying things that you never knew you knew, that you heard yourself receiving from somebody words that absolutely found places within you that you’d thought you had lost, and a sense of an event of a conversation that brought the two of you onto a different plane, and then, fourthly, a conversation that continued to sing in your mind for weeks afterwards? And I’ve had some of them recently, and it’s just absolutely amazing. They’re like, as we would say at home, they’re food and drink for the soul.

Second thing, I think, a question to always ask oneself, is who are you reading? Who are you reading? And where are you stretching your own boundaries? Are you repetitive in that? And one of the first books I read as a child — we had no books at home, but a neighbor of ours had all these books, and he brought loads of books; that’s how I ruined my eyes, like, and I have to wear glasses. [laughs] But one of the first books I read was a book by Willie Sutton, the bank robber, who was doing 30 years for robbing banks. And in the book somebody asked Willie, and they said, Willie, why do you rob banks? And Willie said, Because that’s where the money is. And why do we read books? Because that’s where the wisdom is.

So my professors in colleges always used to say, if you were doing an essay or doing a thesis, the first thing you have to do is read the primary sources and trust your own encounter with them, before you go to the secondary literature. And I’d say to anybody who is listening to us, who is interested in spirituality and who is maybe being coaxed a little away from believing it’s all a naïve, doomed, illusion-ridden thing — pick up something like Meister Eckhart or some one of the mystics and just have a look at it, and you could be surprised what an exciting adventure and homecoming it could become.

[music: “David’s Guitar” by Daithi Sproule]

Tippett: John O’Donohue died in his sleep on January 3, 2008, at the age of 52. This was one of the last interviews he gave. Here, in closing, is one of his well-known poems of blessing, which he wrote for his mother at the time of his father’s death and read aloud to me when we sat together.

O’Donohue: This is a poem I wrote several years ago, and it’s called “Beannacht,” which is the Gaelic word for “blessing.”

[Note: text unavailable due to rights restrictions]

[music: “Cam Ye By Athoil” by Celtic Fiddle Festival]

[music: “King of the Pipers” by Altan]

Tippett: This blessing by John O’Donohue, “Beannacht,” is in his final book, which was published posthumously: To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings. More recently, there is a wonderful new book of conversations with John O’Donohue, called Walking on the Pastures of Wonder, in the UK, and in the U.S. it has the title Walking in Wonder. I wrote the foreword for that one. Of the works John wrote in his lifetime, Anam Cara is a classic.

[music: “King of the Pipers” by Altan]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections