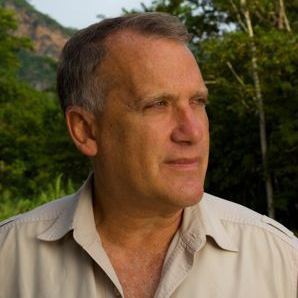

Alan Rabinowitz

We Are All Wildlife

Remembering “the Indiana Jones of wildlife conservation.” The wildness that we don’t feel during our everyday lives. “I was a fluent stutterer and that opened up a whole new avenue in my life.” Escape to places where language isn’t that important.

How to get to the heart of the human experience without speaking? This question drove Alan Rabinowitz, after a childhood with a severe stutter, to become a wildlife biologist and explorer — “the Indiana Jones of wildlife conservation.” He died this month at age 64. He was known for his work with big cats, his discovery of new animal species, and for documenting human cultures believed to be lost. Alan Rabinowitz took our understanding of the animal-human bond to new places, while also being wise about the wilderness of the human experience.

Alan Rabinowitz was the founder and chief science officer of Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization. He was also a spokesman for the Stuttering Foundation and the author of several books, including Life in the Valley of Death, Beyond the Last Village, and An Indomitable Beast. He died of cancer on August 5, 2018.

Find the transcript for this show at onbeing.org.

Image by Steve Winter, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Alan Rabinowitz was the founder and chief science officer of Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization. He was also a spokesman for The Stuttering Foundation and the author of several books, including Life in the Valley of Death, Beyond the Last Village, and An Indomitable Beast. He died of cancer on August 5, 2018.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: How to get to the heart of the human experience without speaking? This question drove Alan Rabinowitz, after a childhood with a severe stutter, to become a wildlife biologist and explorer — “the Indiana Jones of wildlife conservation.” He died this month at age 64. He was known for his work with big cats, his discovery of new animal species, and for documenting human cultures believed to be lost. His work took our understanding of the animal-human bond to new places. Just as intriguingly, Alan Rabinowitz made an intimacy with remote places in the human spirit part of his adventure and his wisdom.

Alan Rabinowitz: I have come face to face with wild tigers. I’ve come face to face with jaguars, lions — all of them. Now, fear was definitely a part of the menagerie of feelings that ran through me. But I also felt flattered to be in the presence of this unbelievable wildness that we don’t feel during our everyday lives.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Ms. Tippett: Alan Rabinowitz was the chief science officer at Panthera, the nonprofit he co-founded to protect the world’s 40 wild cat species. And he was a spokesman for the Stuttering Foundation. We spoke in 2010.

Ms. Tippett: I’d like to start in a place I always start, whoever I’m interviewing, whether they’re a quantum physicist or a wildlife biologist, and I’d like to hear if there was any kind of a religious or spiritual background to your childhood.

Mr. Rabinowitz: I spent my early years going to Hebrew school and learning to be bar mitzvah’d, but it never registered very well with me. In fact, I usually revolted against it for many reasons, because what I was being taught was different from what I was seeing, in terms of how people acted. That was especially poignant for me as a child because I grew up stuttering.

I was a very, very severe stutterer as a child, for as long as I can remember. Because I stuttered, people viewed me in different ways. The New York City school system classified me as handicapped and in special needs, so I was put in special classes from kindergarten until sixth grade. I grew up very much inside of my own head. Because adults didn’t view me as normal, I just thought that I would go into myself and not even try to show adults that I was, indeed, normal and capable of full thought and normal thinking.

Ms. Tippett: And is it right that you did speak to animals?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes, I’ve since learned that stutterers can do at least two things — most stutterers — without stuttering. One is sing, because it opens up the air flow. The other, for psychological reasons, is you can speak to animals. There’s no expectation there, no judgment there. That’s what I would do.

I grew up in New York City. My animals were little green turtles and hamsters and chameleons, and that’s who I would speak to. I would be mute all day long in school, and I would come home and speak to animals.

Ms. Tippett: Did that experience — is there a direct line between that and you growing up and studying biology and becoming a wildlife biologist? Do you think that set your path in life?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Absolutely. I very clearly remember as a young child thinking that I now understand why people don’t treat animals very well. Why nice people, seemingly normal people, will think nothing when their chameleon dries up and dies. Or they didn’t fill the turtle tank with water, and the turtle dies. Or their dog gets sick, and they euthanize it. There was a lack of feeling in all these actions towards animals. I really could see that if animals had a voice, people would not treat them the way they do. I swore to myself as a child that if I was ever able to find my voice, that I would be their voice. I would be there for them. I’m not saying that’s the only reason I took the path I did, but it’s been in my mind for my entire life, trying to give back to these animals, who want nothing more than to live their own lives the best that they can. And we throw up roadblocks, constantly.

Ms. Tippett: I want to talk in a little while about stuttering and some of these larger issues, but I would like to fast forward now to your career as — what have they called you? “The Indiana Jones of wildlife conservation”? [laughs] I’d love for you to fill in some of the blanks because it is an amazing story.

Here’s one milestone I have. The story that, in 1980, you are tracking raccoons and black bears in the Great Smoky Mountains, and this great zoologist, George Schaller, invites you to study jaguars in Belize. But tell me, first of all, how you came to be tracking raccoons and black bears and what you were learning from them.

Mr. Rabinowitz: [laughs] It was more about trying to escape from people, at that time in my life, than running towards something. It was really running away from. I did end up finally, as a senior in college, going to a speech clinic, which taught me how to speak. It didn’t cure stuttering; stuttering doesn’t get cured in that kind of a sense. But you can learn to speak fluently, even as a stutterer.

Ms. Tippett: When you say “to speak fluently as a stutterer,” what are you describing? That you work with the stutter, rather than against it?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Exactly. I learned how to speak fluently. I could control it. I was a fluent stutterer, and that opened up a whole new avenue in my life. But the funny thing was, I learned by that time that I didn’t really care to be among the world of people. All I ever thought I wanted was to speak fluently and be accepted by the world of people and to be so-called normal. Then when I could finally speak fluently, I realized that most people didn’t have that much to say that I was interested in [laughs] — seriously — and that I would rather be with the animals. I applied to graduate school to study biology and to continue my love of science and to escape to places where language wasn’t that important.

Ms. Tippett: So George Schaller’s invitation for you to study jaguars really did take you off in a direction that was formative, didn’t it?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes, it did. At the time, George was studying giant panda bears in China, and there was a bit of a controversy at the time about exactly what panda bears were. Were they a bear? Were they a raccoon? At the time, I was one of the only people in the world, maybe the only person — I don’t know; I’ve never asked George — who was studying both bears and raccoons. He found me and came to look at my work, actually.

Ms. Tippett: Oh, that’s interesting. I have to say that when I look at descriptions of what you’ve done, you have worked in some of the most remote places on Earth. Here’s a description you gave: You’ve lived for days in caves chasing bats; you’ve captured and tracked bears, jaguars, leopards, tigers, and rhinos; discovered new animal species; documented lost cultures, such as the world’s only Mongoloid pygmies. And when I read your writing, you have been passionate about the fact that there are wild places left and that exploration is not something just of the past. Some of your language sounds like these 18th- and 19th-century explorers, many of them British, who also went out to find the lost places.

Mr. Rabinowitz: I’ve read much of them. That’s one of my favorite kinds of books, were these old adventure and exploration novels; people really pitting themselves — I associate myself more with the people who try to pit themselves against environmental hardships, actually, than I do with the pure scientists who go in search of new biological discoveries.

Ms. Tippett: Right — the rare flower that has never been seen.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes.

Ms. Tippett: What names come to mind for you? Who have you enjoyed reading?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Shackleton is one of my true heroes — what that man did, what he was able to live through.

Ms. Tippett: But when I look at the picture, and I think of you together in a sentence with these kinds of figures, I also think you’re animated by very different, late-20th-, early-21st-century goals. There’s a sense — not all of them; they weren’t all out to conquer and “civilize,” but some of them were. And you have added this twist to the notion of exploring and to finding the wild places, and this twist is conservation and preservation.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes. From the earliest time, I not only wanted to go out and challenge myself against the environment, against odds, and explore wild places, I also wanted to be a voice for the animals. I did want to save wildlife. I always appreciated science more than any other course I studied because, to me, science was its own language. Science was a language of truths that would be there apart from whether human beings were on this earth or not. Science presented certain facts and certain realities. It allowed me to delve into a world that didn’t have to do with speech or anything else like that, that was human-centric, but had a life of its own.

Ms. Tippett: You’re thinking of natural laws, the laws of biology.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes. I never enjoyed traveling for traveling’s sake or conquering a mountain for just the mountain’s sake. I really enjoyed and still enjoy conquering a mountain and, at the same time, documenting what the biodiversity is of that mountain and possibly finding some endemic species that nobody either knew about, or we didn’t know enough about, and adding to the scientific literature of that species. And now, I feel, everything has to be taken a step further into conservation, so that everything I do has to do with, “How do we save this wildness or wilderness that we still have on earth?” That’s what has most meaning for me.

[music: “Brushfire” by Ben Vaughn]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, remembering wildlife biologist and explorer Alan Rabinowitz, who died this month.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve been so many places. You’ve done a lot. But illustrate what you just said with a story of one of these experiences you’ve had, where you both had a personal adventure and also have come to understand something about biodiversity and conservation which you’ve been able to share with others.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Oh, that’s a — boy. I’m going to say what first has come to my mind, which has to do with an incredible story that combines cultural diversity and biological diversity, because I never felt that I was that interested in the human side of things until I started reaching some of these more unexplored cultures, or people living different ways of life. I guess, one of the most memorable trips I ever took was to the far, far north of Myanmar, or Burma, up by the Tibetan border. I wrote about this in one of my books, Beyond the Last Village. It took several days, first, of flying smaller and smaller planes, in order to get to the very last place you could fly into on a small twin prop in northern Burma. Then it was about a three- to four-week hike to get to the border of Tibet, up in the snowy mountains. You were actually going up into the lower Himalayas. This follows very much on what you asked earlier because the only documented records at that time from that area were from an early British botanist named Frank Kingdon Ward.

Ms. Tippett: Oh, yes. I know him.

Mr. Rabinowitz: He was an incredibly intrepid explorer who went, on almost no money at all, to go and look for rare orchids, as well as other flowers. I had read everything by him, especially for this part of the world, where he was really interested.

Ms. Tippett: This gets into the Shangri-La stories, right? You’re in that part of the world?

Mr. Rabinowitz: That’s right. Exactly. He actually published some books, which I was able to get a hold of from rare-book stores, where he did some very primitive maps of how he hiked up into this area. But, typical, as a botanist, he never talked about wildlife, and there was no known mention of any of the wildlife up there or of the animals.

Ms. Tippett: He only had eyes for flora. [laughs]

Mr. Rabinowitz: He only had eyes for flowers. That’s right. But I have to admit, as a zoologist, I almost never talk about plants, either. So it goes both ways.

I followed his earlier trail. It wasn’t easy because when I got to the last town where I could fly into, there were almost no people who had been up in that area and knew the best route. Finally, I was able to meet a Tibetan who had come down from that region, having taken more than a month walk to come down. He led us back up there, along with a monk who wanted to go back up there and, interestingly enough, proselytize to the tribal groups up there who were converted to different forms of Christianity.

Ms. Tippett: Oh, really? I thought you were going to say they were animist, but they were …

Mr. Rabinowitz: No. It was a very strange group of us walking up there into the far north. Eventually, after three weeks, we reached the last settlement of human habitation in northern Burma. From there on in, it was pure, rugged, snowy Himalayan mountains to the Tibetan border and over into China. In this area is where I met this last group of Mongoloid pygmies, the only Mongoloid pygmies known in the world, called the Taron. They were going extinct.

Ms. Tippett: Did people know, even, that they still existed, or that they existed there?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Nobody; not the outside world. The reason I even knew about them is because there had been an article written up about their discovery in the international journal Nature in the 1960s. At that time, there were several hundred of them left. But since that time, since the ’60s, nobody really knew anything about them. By the time I got to them — in fact, I didn’t even know when I got to them because the few that were left hid from me. They all ran and hid. It was only when the other tribal group asked them to come out that they would come out and meet me. There were only about 12 of them left.

Ms. Tippett: Right. You have pictures in one of your books, and they’re just amazing to look at.

Mr. Rabinowitz: I have to say, this — they taught me, more than anything else — was almost a defining moment of my life because it was a time when I was trying to figure out whether I wanted to have children; whether my marriage would really work out; where my life was actually going as I figured things out. And here, this leader of the Taron, who couldn’t speak my language — in fact, he didn’t speak Burmese, either. It was the Taron dialect. If I really wanted to talk to them, I had to go through three different translators. But I didn’t spend much time talking to him. He and I went off by ourselves, up into the snowy mountains for a couple of days, and we were alone together. This was exactly everything I had looked for: to figure out how you get to the heart of the human spirit without speaking, without an actual human voice. And we were able to do that.

Ms. Tippett: Well, was it just about presence? Was it about just physical presence, or doing things together? What happened for those two days?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Again, it’s hard to put into words, because it was all nonverbal.

Ms. Tippett: It wasn’t word-based.

Mr. Rabinowitz: We couldn’t be more different. Here’s this little guy who’s under five feet tall, four feet-something, and from this remote area in northern Myanmar, untouched by the outside world. Here I am, a New York Jewish kid that grew up stuttering and couldn’t deal with the world of people that was all around me. And we actually seemed to just fall into a balance of commonness that. We would sit around the fire at night and smile at one another and touch one another and know what the other needed.

Ms. Tippett: Make eye contact and those other kinds of communication that we undervalue in Western culture.

Mr. Rabinowitz: And then he started making gestures. He started making gestures about young children, which I didn’t quite understand at first. Only when we got back was I able to confirm what he was trying to say to me. He wanted to know why I didn’t have any children.

I asked him through these translators — he didn’t even know I didn’t have any children. I said, “Why do you assume I have no children?” And he said, “Because you act like a man who still has this deep, deep hole inside of him.”

“And I know that hole, and I can’t have any children because nobody will mate with me. Nobody will be my partner,” because he was the last viable Taron living. And it was after my time with Dawi that I returned to the United States, and I looked upon my marriage in a completely different way.

I decided to have children as well, which has been the best thing that’s ever happened to me.

[music: “Magna Carta” by Mark Orton]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, more conversation with Alan Rabinowitz. Subscribe to On Being on Apple Podcasts to listen again and discover produced and unedited versions of everything we create.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, we’re remembering the wildlife biologist Alan Rabinowitz, who died this month at the age of 64. He was known as “the Indiana Jones of wildlife conservation” — an old-fashioned explorer in our world’s last wild places. He expanded our understanding of the animal-human bond and made an intimacy with remote places in the human spirit part of his adventure and his wisdom.

Ms. Tippett: It seems to me, when I read you and read about you, that even in the last few years you’ve kind of turned a corner in terms of seeing that connection between the preservation of animal habitats and the vitality of human communities. Would that be fair?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes, it would. Whether I like it or not, the sustainability of wilderness, of wildlife populations, is in the hands of the human race. There is a direct linkage — and I think there always will be — between the understanding and the activities of people, be they at the local level or at the national level, and the well-being and preservation of wildlife and wilderness areas. So I can’t separate them as I wanted to when I was younger as I thought I could. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Here are some lines you wrote in 2006. You wrote: “It is not earth-shattering news, that animals and people must live together if there is to be any true ‘wildness’ for future generations. I am among the majority of scientists and conservationists who have done little to effectively foster this relationship in a sustainable manner. Until now, that is.” What brought that home for you? What changed for you?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Being among these remote tribal groups, or remote communities, which lived with wildlife, which accepted the wilderness around them, which showed me a model for how people can live with their environment and still move forward. I’m not saying that these people should be kept — in fact, I advocate opposite. There are many people who go in and find a tribal group or a remote village and say, “We shouldn’t touch this place. This should be left as is.” Well, I have never been to a remote area where the people don’t want a better life, where the people are not aware of the fact that many of their babies die, and they have a lot of illnesses that the outside world doesn’t have, and they would rather have more than they have then. I think it’s wrong to try to hold that back from them. Where the balance has to occur is figuring out how to enable and empower local communities to live better — have a better life, have better medical care, have lower infant mortality — and yet, at the same time, balance that with giving life, giving an area of the world to the wilderness and the wildlife that live with these people. That can be done. It’s not pie in the sky.

Ms. Tippett: Right. You’ve also talked about a success story of Maya Indians, who used to kill jaguars, who have become wardens to those animals.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes. The Mayans and many other groups throughout jaguar range — jaguars still get killed a lot, but not nearly to the extent that they used to. And it’s not because these poor communities or these indigenous groups had some kind of a conservation epiphany. It’s because they had a growing economic awareness. It’s because they — all of a sudden, their lives could be better off because people came down and paid money and stayed in their local thatched motels or huts to see jaguars or to follow jaguar trails — than they ever made from cutting all the forest and just growing corn and selling the corn and just barely living, barely surviving. Their lives were better for it.

In my early days, I never would meet a local person who dared walk in the forest without a gun. They just felt that it was crazy to do that. It was just too dangerous out there. I rarely meet a Mayan now in the same area, or a local person, who is carrying a gun. It’s not because they are mandated not to. I ask them, “Why aren’t you carrying something, your machete, your gun?” They said, “We know that there’s no need to. If we see a jaguar, we stop on our bicycle, and we watch it now.”

That’s people starting to live with the big cats. It can be done, just like people live with mountain lions in the United States. Will it mean that there’ll be no problems, no conflicts? No, it doesn’t mean that. But we have to view it in the same way as we view conflicts in our everyday life. I can’t understand why people classify conservation or living with animals as different from the problems we have every day of living with other people in our town or in our city.

Ms. Tippett: You said a little while ago, we’re all human, but maybe we’re all also wildlife. [laughs]

Mr. Rabinowitz: Oh, exactly. No, that’s exactly right.

Ms. Tippett: There’s a phrase that I think is often used romantically, and there’s a lot of energy around this now, talking about the “animal-human bond.” So when people talk about that in the United States, they’re talking about our relationships with our dogs and our cats, for the most part. But I just wonder, for you, with all these years you’ve spent in the presence of big cats, for example, animals with whom many people have, for understandable reasons, not felt safe walking in the presence of without a gun — have you learned things about the animal-human bond that would stretch our imagination about that?

Mr. Rabinowitz: I’m trying to think how I explain what I feel without seeming like it verges off into the almost-supernatural because it’s not supernatural. I do feel a very close bond with animals — not just with the big cats, but with animals as a whole. It doesn’t mean I don’t feel fear and respect for them. In fact, I’m often angered by TV shows or by commentaries that I hear by people who feel that humans can truly bond with wild animals to where you can go up and touch them or sleep among them or that kind of thing. Invariably, those people either get killed or mauled, because they are a different species from us. There is a wildness about them. I have come face-to-face with wild tigers. I have come face-to-face with jaguars, lions — all of them. Almost all — not yet a snow leopard.

I felt great fear. Fear was definitely a part of the menagerie of feelings that ran through me. But I also felt flattered to be in the presence of this unbelievable wildness that we don’t feel during our everyday lives. Could I bond with them? In a way, yes. And yet, in a way, I almost learned the opposite. By spending so much time in the jungle with these wild cats, and sometimes, significant time with them face-to-face, I also came to realize that there would always be a wall between us, a wall that couldn’t be breached and, really, shouldn’t be breached because we were of two different worlds — worlds that could come together on certain things, but that just had to be apart on others for both of us to live properly within this larger world.

Ms. Tippett: When you talked about going away with — what was his name? The pygmy, the man in Burma …

Mr. Rabinowitz: Dawi.

Ms. Tippett: … for two days, and you had all these nonverbal ways of communicating — do you also have that experience with animals?

Mr. Rabinowitz: The nonverbal communication I could feel with the animals — and with the big cats, especially — since I was a child. My father, he didn’t know how to handle a lot of what was going on inside of me, but he did realize that I had certain outlets that just made me feel good and relaxed, and I could speak a little better after those. One of those was taking me to the Bronx Zoo.

Ms. Tippett: Really?

Mr. Rabinowitz: He would take me to the Bronx Zoo, and we would go straight for a building that is still there. It’s no longer what it was, but it was called the Great Cat House. And it just had cats, big cats, cage after cage, like the old zoos did. You would walk in there, and the sounds and the smells would be just overwhelming. It would stink of wildness. The jaguar would be coughing, and the tiger would be roaring. The cacophony of sound would both terrorize you and thrill you at the same time.

I’d just watch them go back and forth, back and forth. They’d stare at me, and I’d stare at them. I felt more of a nonverbal communication with the big cats as a child than I did with any human being I knew at that time. Unfortunately, I can’t say that the communication I felt was good. I empathized with this incredible frustration and anger and sadness. Maybe I was projecting, but I don’t think so. When I was a child, I repeatedly talked to the animals through the cages of the Great Cat House, and I would repeatedly say to them, “I’ll try to find a place for us.”

I didn’t even know what I was saying. I didn’t even know why I was saying it. And it came back to me years later, came back to me vividly, when I was walking through the Cockscomb Jaguar Preserve in Belize, which I had set up as the world’s first jaguar preserve, and I saw the tracks of a large male jaguar. I thought, “This is great. I haven’t seen this animal before when I was studying here.”

I started following it, and several hours later when it was getting dark, and I knew I was alone, and I couldn’t just keep on hiking in the dark, I turned around, and there was the jaguar, in back of me.

The jaguar had circled around and was following me. This was one of those bonding moments, if you want to call it that; but it was. My first feeling, of course — this is a jaguar. This is the biggest cat in the Western Hemisphere. This is the sumo wrestler [laughs] of cats. It’s a massively powerful animal. There was nothing I could do if it wanted to kill me. So my first feelings were terror, fear. Oh, my God. What am I going to do? So I thought, “OK. Make yourself subdominant. Make yourself small.” I squatted down, and I was expecting the jaguar — hoping the jaguar would just walk off. Although I loved watching it, I was also scared.

The jaguar just sat down. He just sits there on the trail — the trail I have to go back on — sitting there, looking at me. I remember thinking how great this was, and at the same time, thinking, “Well, what the hell am I supposed to do now? Because he’s not going to sit there forever.” I stood up and stepped back and tripped and fell down on my back. I wasn’t sure — in the instant I was falling, thinking, “Oh, the jaguar’s just going to come at me now.” And the jaguar let out kind of a guttural growl and stood up and walked towards the forest. Right before it went into the forest, it turned, and it looked back at me for a few seconds, and our eyes met. I remembered that look so clearly from the cages in the cat house at the Bronx Zoo.

And he turned and went back into the woods. He had his home.

Ms. Tippett: This time he could walk away, right?

Mr. Rabinowitz: He could walk away. We both could. We both walked away completely different beings than we were when I was a child.

[music: “The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born” by Marc Anderson]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, remembering wildlife biologist and explorer Alan Rabinowitz, who died this month.

Ms. Tippett: Something that’s striking to me is — when you talk about that early animating idea for you — that you wanted to live apart from other people, and animals wanted to live apart from other people. Clearly, that’s evolved and developed, even as you told the story of deciding to have a family. It seems to me that even the science has caught up with that. That, in your lifetime — this was new information to me — that this classic conservation strategy of preserving habitat — hence, that separateness, that apartness — is not the defense against extinction that scientists thought even just a few generations ago. So what you’re working on now are these genetic corridors, which is just more about integration. Is that correct?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Absolutely. That’s right. It’s about these big cats living within the human landscape — being able, at least, to traverse the human landscape. I grew up professionally with the traditional paradigm for wildlife conservation: that the way to save wildlife, the way to save the big things, especially, was to try to make a huge protected area for them — hard boundaries. Put guards on those boundaries. You keep the people — the people live outside, and the animals live inside.

Now, we need those wild areas, frankly, those wild pockets where the wildlife have its home, and that’s the animals’ home first, and people’s home is someplace else. That’s needed. But what we do understand now is: If that’s the end point of conservation, that conservation will fail, especially for the big, wide-ranging mammals like the big cats. These animals need to move. They need to exchange their genetic material. Locking up these animals — even in a nice, big park — will be no more of a success for them than it would be if you put a bunch of human beings on an island where they were incapable of getting off that island, and thinking that’s going to be a new human race.

Ms. Tippett: Right, well, isn’t it very much like the Mongoloid pygmies who you met?

Mr. Rabinowitz: That’s right. It is like the Mongoloid pygmies.

Ms. Tippett: I’d like to circle back a little bit — near where we started with the stuttering, which led you to animals, or initially led you to a different kind of relationship with them — just to say that when you talk about what helped you was becoming a fluent stutterer, which was working with it, rather than denying it. Clearly, you’ve continued to do that. It reminds me of what I hear about healing and wholeness in all kinds of conversations I have. That, in fact, being a whole person is about taking in whatever our wounds are, whatever our fears, and then integrating them into our identity. And you’ve done that.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Well, I’ve tried to do it. It’s been a very long …

Ms. Tippett: It’s the work of a lifetime.

Mr. Rabinowitz: It is. But I guess I realized most how much I had gotten there when, in 2002, I was diagnosed with cancer. I have something called CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which has no cure at this time. But they diagnosed it at an early stage in me, fortunately. It’s slow. I’m progressing, but it’s slow. The reason I bring that up is it was of course a shock to me. I always prided myself on staying in shape; being very, very physical; being very, very healthy.

Ms. Tippett: Well, you’re an Indiana Jones figure, after all.

Mr. Rabinowitz: Plus, I always thought I could fight everything. I really believed anything I wanted to do, I could overcome. And here I’m being told I’ve got something which is incurable. I was told by the therapist I was advised to go to that I would go through these stages of cancer that, I guess, most people go through — stages like anger and denial and “Why me?” and all of that. And I said to the therapist, “I can tell you right now, I’m not going to go through any of those stages. I’ll go through sadness, which I’m going through now because I have two young children, and I’m sad thinking that I’m not sure where I’ll be when they’re older. But I will never go through ‘Why me?’ or the denial.” I went through all that with the stuttering. For decades, I went through that with the stuttering and came to a place of comfort, of OK-ness, because not only can things like that really, truly make you strong — although people say that, it really is true — stuttering gave me my life.

Now, just as I was starting to get a bit tired and actually considering slowing down, now I’m told that I have cancer. And what that’s done is, that put away all thoughts of slowing down, all thoughts of being tired, and it’s another wake-up call. Why me? Why not me? And why isn’t it a good thing? Now I’ll accomplish more. Now I will never, never wake up a day and sit back and thinking, “This is enough.” All I ever do is think of the things that I haven’t done yet and that still need doing. So it’s a good thing.

I think what you were saying about taking whatever it is — taking a challenge, taking life as it comes to you — and incorporating that as part of your psyche, as part of who you are, is really what life should be about.

Ms. Tippett: It’s kind of an amazing thing you’re experiencing right now. I mean, mortality is not special, right?

Mr. Rabinowitz: No.

Ms. Tippett: It’s not at all special, but it is something that we manage to avoid an awareness of, especially in Western culture. It’s like you’re being confronted with your mortality, and yet, at a pace. You get to live with that awareness for a while. This is kind of a huge question, but I wonder how this experience you have of living with this illness now — how does that flow into how you do take stock of this life you’ve lived and especially this work you’ve done with animals — and increasingly with animals and human beings together?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Well, I can’t say it drives me. I’ve always been such a driven, passionate person. So it just doesn’t let me slow down now. I actually use it in some way. It’s really helped me in Myanmar. It’s helped me tremendously with the generals.

Ms. Tippett: How’s that?

Mr. Rabinowitz: The generals say to me, because they’ve read about it, and they’ve heard about it, and they say, “You have cancer. What are you doing here in Burma? It’s not a healthy country. What are you doing, going in the jungle with tigers?” It’s enabled them to see to my core better, to really have even more of a respect for me. And actually, I think it’s truly helped me get things through the cabinet, new laws in this area protected, more than I could’ve otherwise, because they really realize, as they should, that there’s no ulterior motive here. This is what it’s about. Why shouldn’t I be here? Because I have cancer is why I’m here, is why I’m pushing it.

Ms. Tippett: Is it right that your son is a stutterer?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes, he is.

Ms. Tippett: There’s a very rich and big reality that you have to navigate, in yourself and with your children and with your son.

Mr. Rabinowitz: That’s been the biggest challenge. I can deal much easier with a tiger facing me, with being told I have cancer, than I can with my son coming home and seeming sad. As much as I can say now, I’m so glad I was a stutterer, and it really is a gift, it’s a gift I wouldn’t wish on anybody.

Ms. Tippett: But he has the benefit of what you know and what you’ve been through.

Mr. Rabinowitz: That’s right. He does. That’s been good, actually. First of all, because of my knowledge, I was able to get him treatment. We acknowledged it very soon. I got it diagnosed very early, and he’s actually more fluent than I am. But of course, it’s still there. It’s a neurological thing, and some days are better than others. Some days are worse. He will not think anything of coming to listen to me lecture or give a talk, and saying, “Daddy, you stuttered a bunch there.”

“You had,” he calls it “bumpy speech.” “You had a really bumpy speech there.” I say, “I know I did. Your speech is so much better than mine.” Or I’ll say to him, “Alex, your speech is bumpy today.” And he’ll say, “Oh, yours is much worse than mine.” And I said, “I know mine is, and that’s right. I don’t want yours to be as bad as mine.” But he’s very open about it. I love that because I could never talk about it.

Ms. Tippett: Does he have a special understanding of your connection with animals?

Mr. Rabinowitz: Yes, he does. He says he wants to grow up and be a zoologist, and I’m telling him he should think hard about that. [laughs] I’m not sure I wish that on him, either. But, yes, I think he understands me more than I almost realize now.

It’s hard because I also travel a lot. I’m very torn — that’s the other thing. When I was diagnosed at first with cancer, I was told that while it’s slow, if I keep on doing what I do, and I get sick as I have many times in my life in the field — with malaria or dengue fever or typhus or typhoid — there’s a potential I could speed this leukemia up because I will be kicking my immune system into hard drive. So for a little while I thought, “OK, well then, I’m going to try to prolong my life, and I’ll go in the field less. I’ll stay at home more.” I was going crazy, and I wasn’t the father I wanted to be to my children. My wife, of course, told me, “Get back in the field” — because I was driving her crazy.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Mr. Rabinowitz: So I really realized — one day, I came out of one of the rooms of my house, and I watched my son watching a videotape of me, a show that was done years ago, called “Champions of the Wild,” about me with jaguars. He thought it was his cartoons, and he accidentally put in this tape of me, and he started watching it. It just shows how fate intervenes because that was the point at which I realized that regardless of what happened because of it, I had to live the life that defined me the best, both to myself and to my family.

[music: “Hop” by Viktor Krauss]

Ms. Tippett: This conversation took place in 2010. Alan Rabinowitz died of cancer on August 5, 2018 at the age of 64. He was founder and chief science officer of Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization. He was also a spokesman for the Stuttering Foundation and the author of several books, including Life in the Valley of Death, Beyond the Last Village, and An Indomitable Beast.

Staff: On Being is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Casper ter Kuile, Angie Thurston, Sue Phillips, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Damon Lee, and Jeffrey Bissoy.

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice you hear, singing our final credits in each show, is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections