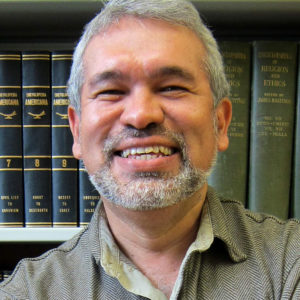

Manuel Vasquez

Latino Migrations and the Changing Face of Religion in the Americas

Vásquez believes that in the global age, religious dynamics may have a boomerang effect across the Americas with dramatic consequences. We explore how religion will shape the increasing Hispanic population and how religion itself might be changed.

Image by Gabriel Perez/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Manuel Vásquez is associate professor of religion at the University of Florida, and author of Globalizing the Sacred: Religion Across the Americas.

Transcript

July 26, 2007

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Latino Migrations and the Changing Face of Religion in the Americas.” By 2050, it is estimated that nearly a quarter of the U.S. population will be of Hispanic descent. And my guest, Manuel Vásquez, says we have not grasped the way U.S. culture will be changed by imported religious and spiritual worldviews. Indigenous religious practices are growing more influential, not less so in the global age

MR. MANUEL VÁSQUEZ: Religion is one of the best vehicles to deal with both the local and personal and also the global and the universal. Religions have been doing this for centuries. They have universal messages of salvation and very personal strategies for coping with chaos.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us. I’m Krista Tippett. When we speak about immigrants, we tend to focus on economic and political impact. This hour, we explore how religious and spiritual worldviews anchor Latino cultures and are reshaping North American culture in fascinating ways. Some 15 percent of the U.S. population is now of Hispanic descent. And that is expected to approach a quarter of the population by mid-century.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Latino Migrations and the Changing Face of Religion in the Americas.”

Manuel Vásquez is a Salvadoran-American scholar of religion at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He and his colleagues are involved in long-term studies of the role of religion in diverse Latino-immigrant communities, from Mexicans in suburban Atlanta to Guatemalan Mayans in southern Florida. Religion plays a powerful, paradoxical role in these lives, he says, helping people navigate change and adapt, and at the same time, to maintain strong identities and rich connection to their original culture.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: In one of the communities that we’re looking at, people have retired from New York, from Boston, and they’re going to Florida to enjoy the warmth. But in order to take care of their personal needs, they are relying on a growing immigrant population coming from Guatemala. And they these Mayas basically are sort of plopped into a very hyper-modern society with all the luxuries of a planned city.

And they are bringing their traditions of saints and spirits into this community. And they parade through the city, and now you have the local population coming in, participating in this and saying, ‘Well, isn’t this great that we have this experience of culture.’ But then, at the same time, we have tensions, right? Because it’s OK to have a colorful festival with music and good food, ethnic manifestations that we want our community to have. But at the same time, we are concerned that our space is being colonized by someone else.

MS. TIPPETT: To understand why such dynamics are telling a new American story, Manuel Vásquez points back to events that began in the 1960s. Like other scholars, he views the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act as a watershed in American history, though it may have gone unnoticed by many amidst the other social dramas of the era. That act abolished previous country of origin quotas. So into the 1960s, over 80 percent of immigrants to the United States were from Europe. Today, 13 percent come from Europe, 26 percent from Asia, and fully half from Latin America.

Hispanic immigrants to the U.S. are predominantly Roman Catholic, though they bring diverse sensibilities from the recent history of their region. In the 1960s, Latin America became the birthplace and testing ground of liberation theology, which emphasizes the needs of the poor and social justice. In the ’70s and ’80s, Latin American Catholic leaders became increasingly involved on both sides of political and social conflicts, conflicts which many fled by migrating to the U.S.

When Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador condemned government death squads in 1980, for example, he himself was assassinated. Manuel Vásquez knows these dynamics from his personal history. And they eventually led to his scholarly interest in Latino religions and globalization.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: It goes back to my childhood in El Salvador. I was trained by the Jesuits there. And at the time that I was trained, the Jesuits were at the forefront of what is called progressive Catholicism associated with liberation theology in Christian-based communities, an attempt to do precisely what you do in your program, which is to link faith and life very closely. And I was trained by them. And El Salvador was undergoing major changes at the time. There was a lot of repression and social ferment.

MS. TIPPETT: When are we talking? What, what year?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: We’re talking about the early 1970s.

MS. TIPPETT: And when you say you were trained by them, you were educated as a child or did you go into seminary?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: I went to a Jesuit, yeah, no, Jesuit high school.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: And at the time, they were implementing the changes in Vatican II

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: the opening to modernity and to read the signs of the time. And the signs of the time in Latin America were widespread poverty, social ferment. People were beginning to organize, to claim their rights. And so I came to the Jesuit high school where they were beginning to introduce this kind of sociological outlook to the educational system. For them, social justice was not something that was only a human enterprise. It was a divine mandate. And they even sacrificed their lives because many of these Jesuits were assassinated

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: you know, in their fights.

MS. TIPPETT: The Jesuits in El Salvador who you

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah. They you know, after the killing of Monsignor Romero

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Oscar Romero, there was a lot of repression against the progressive Church in El Salvador. So my teachers, both at the high school at the university, were gunned down. The army came in one night when there was a guerilla offensive, and they took them out of their dormitories and executed them. And, you know, the story is that they aimed for their brains. They wanted to destroy the brains because they felt that the Jesuits, with all their teaching of liberation and human rights and, and consciousness-raising, had stirred up the revolutionaries.

And as a result, they wanted to, to kill the brains of the operation. So these people sacrificed a lot for justice, and I was moved by that. And so I became interested in that. And I went to Brazil to do research on base communities, small organizations that were trying to promote social justice and the reading of the Bible.

MS. TIPPETT: Another extension of that same impulse, right?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: And the same, the same impulse, yeah. And the people basically read the Bible in their homes, and they interpreted the word of God. And they saw that God wanted justice and that God was a God of life, opposed to a lot of the oppressive structures that were imposed on them. And so I went to study them. And I, again, was moved by poor people who, even though they had maybe not gone beyond second grade in terms of education, were very eloquent in the presentation of their faith experience.

And so I was interested in that. And initially, I was interested in just doing a study of a base community, doing kind of a micro study of it, interviewing people. But as I went into the local, I began to see that you could not understand the local without focusing on the global, because a lot of the problems that were affecting them were problems that were global problems changes in the economy, changes in the government, migration. A lot of the people were migrating to the United States in search for opportunities. And so as a result, I said, ‘Well, if I’m interested in the local and in the everyday, I need to understand the global.’ And that’s how I began to get interested in following the immigrants.

MS. TIPPETT: Scholar of religion and social change Manuel Vásquez.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: We all learn in school that America was shaped by immigrants, who left their country of origin behind, came here, and assimilated within a couple of generations. Now, modern communications and transportation make it possible for immigrants to maintain rich cross-border ties and essentially to live in multiple places. This is a pattern common among the Hispanic immigrants whom Manuel Vásquez studies.

He says he does not see this as a failure of the American experiment but as a new chapter in the age-old story of human migration. He calls it transnationalism.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: In other words, this is not an exclusive allegiance that we’re talking about here. We’re talking about here a kind of citizenship, a kind of belonging beyond the kind of single assimilationist approach that was a traditional approach that you’re talking about. I’d like to give the image of the horticultural model of immigration in the past.

MS. TIPPETT: And what’s that?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Immigrants were like plants, uprooted from their former homelands because of political violence, famine. So you have the Irish coming in the 1840s, uprooted from a poor Europe, and they come here. And so they had to leave behind their roots in order to be replanted here in a new land. And they forget about their country of origin.

What transnationalism says is that you don’t have to give up your roots. You can be multiply imbedded in many countries and still belong you know, have families here in the United States and also back home, send remittances and support families back home. But at the same time, make sure that you buy your house here, make sure that your kids are educated in the American system and, you know, invest here in this, in this life.

MS. TIPPETT: And I wonder how, as you study this, all this cluster of issues around immigration and globalization, how your focus on religion and religious sensibilities and religious practices also, you know, does that give you a different imagination about what all this means, and what the implications are and how it works, a different imagination than Americans, again, might have?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, I think this is a very good question. Because normally, we tend to see immigrants as, as a kind of Homo Economicus.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: You know, they come, they come here

MS. TIPPETT: We talk about them as economic actors, don’t we? Yeah.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, the economic actors.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: They come here because they you know, there are, of course, better jobs here, higher wages here. They don’t have jobs in their, in their home countries. And so the idea is that because there is a wage differential, they, of course, have to come here because, you know, who wouldn’t come here with better jobs and more benefits?

But a lot of these immigrants, even though that is a strong motivation, a lot of these immigrants also come for religious reasons. You know, you have immigrants who come here to this country as missionaries. They see the United States as in need of reform. So when we talk about family values, many of these immigrants bring very conservative family values to this country. So you’ve got many Pentecostals who say, ‘I’m going to America because I want to convert who needs to be converted.’

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, so that’s those are special cases, but you have religious immigrants. You also have religious readings of the economics and politics of immigration. Many of these immigrants interpret their journey across borders as a journey of conversion, as a journey of transformation, of religious growth. And they invoke saints along the way. They ask for God’s help as they cross borders.

So these immigrants read their migration story as part of the divine story, where their lives are fitting as part of a mission that God has for them. A lot of the immigrants will tell you, ‘Yes, I came to look for jobs. Yes, I came for to give a better life for my children. And, you know, it’s part of God’s plan for me. I’m here because God has given me this message that I should come up here and do this.’

MS. TIPPETT: And you hear you’ve heard people, many people speaking that way? I mean, you know, that’s not, those are not the kinds of quotes that we get in newspaper accounts of immigrants and why they’re here.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: No, you don’t get them because I think if you go to churches, and the important point to go to churches is because immigrants, one of the first things they do when they arrive in the United States is they create their own churches because their own churches are safe spaces where they can worship, they can come together, they can share in their, often in their native language. And they serve, also, churches serve also as self-help networks that provide the assistance that is not there for many immigrants, particularly in places where immigration hasn’t taken place. And so churches provide the first way for them to organize as a community.

MS. TIPPETT: So, you know, an interesting insight that comes through to me in your work and also in other research I know of about globalization, including, you know, some of Peter Berger’s work and in an interview I had with him, is that religion, in fact, you know, contrary to the idea that was prevalent a couple of decades ago, especially among sociologists, that as the world became more plural and more sophisticated and more global, religion would be less important. In fact, religious traditions and beliefs and practices are very critical tools and, for people of many traditions, you know, we’re tending to talk here very much about Christians because that is the predominant tradition of Latin America, but this is true across traditions, that religious practices are critical tools as people navigate, both becoming part of a more universal world, a global world, and at the same time maintaining their identity and stability.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, you put it beautifully. I couldn’t have said it better myself. So yeah, what you sketched initially was the so-called secularization pieces, which basically said that with modernity, religion would be kicked out of the public sphere, in effect, and that religion would become privatized. It would become more of a matter of personal choice, and that people would have a religious market where they would go choose whatever works for them at a particular moment, and so religion would not have any public force. But what we’re seeing is very public religions. We’re seeing religions that make, as you say, universal claims about truth and about foundations. That’s the whole question about fundamentalism, making claims about the true way of being religious.

And then at the same time, these religions help the individual get a sense of selfhood. Pick any religion. Pick Pentecostalism, sees itself as a universal message of salvation and, you know, it has the so-called “great commission” to go out and convert the nations of the world. But at the same time, Pentecostalism really takes care of the individual at the very personal level, from helping the individual deal with the evils of drinking, drugs, domestic violence

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: to helping the individual, as you say, navigate through the process of migration because when you migrate to a new place, especially if you’re a single man, many of the people that we study, you know, the immigrant we study in Florida work in the agricultural sector, and they’re single men. They have left their families behind and they come here and they’re around men. And there are all sorts of temptations that appear to them. And churches then provide these resources for them to have a safe space where they can maintain a certain purity from the world outside and keep focused on the family, which is back home. So getting back to your question, religion is one of the best vehicles to deal with both the local and personal and also the global and the universal. Religions have been doing this for centuries. They have universal messages of salvation and very personal strategies for coping with chaos.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Salvadoran-American religious scholar Manuel Vásquez. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Latino Migrations and the Changing Face of Religion in the Americas.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: The rise of Pentecostal Christianity, as Manuel Vásquez just mentioned, is an important religious trend and a formative aspect of the new Latino imprint on U.S. culture. It’s estimated that 8,000 to 9,000 people a day across Latin America convert to charismatic or Pentecostal Christianity. This is eroding the historic influence of Roman Catholicism on every aspect of life in Latin American countries. Guatemala is now a majority Pentecostal country.

Pope Benedict XVI recently made a visit to bolster the Catholic presence in Brazil, which is now nearly half Pentecostal. Charismatic spirituality has, in turn, infused Roman Catholic and other traditions south and north of the border, with its emphasis on spiritual gifts of healing and speaking in tongues, and most of all, with an insistence on the equality of every believer before God. And Pentecostalism was originally a U.S. export with roots in Los Angeles. For Manuel Vásquez, this is just one example of a larger pattern of exchange that has characterized the history of the Americas.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Pentecostalism is, I think, the quintessential hemispheric religion because it, you know, emerges in the United States in the early 1900s in the Azusa Revival.

MS. TIPPETT: In Los Angeles.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: In Los Angeles, and you already had Latinos there. Many Mexican-Americans involved in that revival, and they themselves begin to take the message back home to Latin America. They take it within two, three years to Mexico, to Puerto Rico, Brazil, and right away they start to create their churches. The Assemblies of God have been established in Latin America. They have a long trajectory. But as they do that, they begin to indigenize. They begin to take in some of the aspects of the local culture, not only the language, but also some of the cultural patterns. You know, if they need to speak to indigenous populations, they need to translate the Bible to Quechua. But they also need to deal with the cosmology of the Quechua in order to make sense of what the Quechua are experiencing.

So the figure of the devil, as the Quechua understand it, becomes incorporated into the Pentecostal narrative in that region. And then, as these churches are indigenized and as they grow very fast in relation to Catholicism, then they begin to be exported back to the United States. They begin to come into the United States with immigration. And so now we have Pentecostal churches that have very clear Latin American flavor but are appealing to larger segments of the population, not only Latinos but also African-Americans and even your Americans.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, let me just, you know, I think it’s also worth pointing out that the theology and the sensibility of Pentecostalism, it says so much about the individual’s direct relationship with God.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: And also, I think, Pentecostalism coming into another culture in contrast to, say, Catholicism. Roman Catholicism coming into another culture did not bring with it, and still today would not bring with it, its vast hierarchy and this long tradition that, in some sense, need to be imposed. So there’s something organic about what you’re describing.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yes. I think, you know, some people have argued that Pentecostalism is not concerned particularly with theology, that Pentecostalism is more of an embodied kind of experience

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: that has to do with the experience of the Holy Spirit and the transformative power that it has in the life of the individual. And so in that sense, Pentecostals, although they have a theology, they’re not interested in dogma; they’re not interested in the rational analysis of the effervescence that is behind their religion. That’s why it’s very adaptable

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: because it can really focus on the pragmatic needs, on the practical needs, the everyday needs of a particular population, especially populations which are at the margins of society poor people, indigenous people, people who have been devalued. All of a sudden, they feel themselves empowered by the Holy Spirit and they speak a language that justifies and legitimates their position in the world. Now Catholicism, it’s true, it brings a hierarchical setup in a very complex theology. However, there are forms of popular Catholicism that are also very much embodied and very much all about the senses

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: particularly the cult of the saints or Marian devotions, the devotions to Mary. They’re all about the senses, they’re all about the incense, they’re about the music, the colors, the processions, the feel of the personal relationship with your patron saint. And these traditions are traditions that are still thriving despite the fact that Pentecostalism and evangelical Christianity is growing very fast in the region.

MS. TIPPETT: Religious scholar and author Manuel Vásquez. About one-third of Roman Catholics in the United States are now Hispanic. Latino Catholics often import an exuberant worship style and a mix of perspectives counterintuitive in North American culture, an activist’s concern for social justice combined with conservative moral and family values.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: This music comes from one community Manuel Vásquez and his colleagues have studied in Texas. The Basilica of Our Lady of San Juan is a Roman Catholic church with a strong charismatic influence. The priest there says that he watches Catholic religious television to learn more about church doctrine. He watches an evangelical station to learn how to preach. He translates some worship songs into Hebrew to be more universal than Spanish or English. And a mariachi band is likely to be playing as thousands of people gather every Sunday.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more from Manuel Vásquez, including stories from his research on pan-Mayan communities in suburban Florida and Pentecostal churches ministering transnationally to Salvadoran gangs. If you’d like to learn more about the appeal of Pentecostalism and the Charismatic movement among Latino immigrants, visit our Web site, speakingoffaith.org. We posted some helpful essays and downloadable MP3s of my conversation with Marie Friedmann Marquardt who’s co-authored a book with Manuel Vásquez, Globalizing the Sacred. And we’re making it easier for you to listen to Speaking of Faith when it best suits your life. Subscribe to our podcast for a schedule of download or access the audios as part of our e-mail newsletter. Discover more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Sound bite of music]

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Latino Migrations and the Changing Face of Religion in the Americas.”

My guest, Manuel Vásquez, is a scholar of religion and social change at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He grew up in El Salvador and is now involved in long-term studies of Latino immigrants in the United States. He’s been describing the novel religious sensibilities these immigrants bring to the U.S. public religious sphere. He has a special interest in what he calls the “little religions,” local practices and beliefs by which human beings navigate the opportunities and dislocations of the global era. And Manuel Vásquez says that for all our talk of pluralism, we have not grasped the way U.S. culture will be reshaped by the expanding range of religious and spiritual worldviews now being imported.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: So you have a transformation that you have people coming from Latin America and Asia and Africa, bringing traditions that are not just Christian, where we have increasing diversity religiously, we have Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, people who practice African-based religions such as Santería, Candomblé. And so we have a religious diversity that is really posing a challenge to the ways in which we understand pluralism in this country.

MS. TIPPETT: Isn’t it something like the projection is that by 2050, there will be

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: slightly more than 20 percent of the American population would have Latino origin.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Right, right. You know, even then there are 40 million Latinos

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: in this country, so it’s a substantial amount. But we’re going to go up to close to 80 million by 2050, and that’s a tremendous increase. And so it’s changing the face of what it means to be American and raising the issue again of, you know, loyalty and belonging

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: and language. And not only that, but what are the values, the core values, that will drive our society? Are they going to be, you know, freedom of conscience, tolerance for religious practices? You know, what’s in store for us as we have people who have different experiences, different kinds of modernity coming in, coming from India, from Brazil, from China. You know, what does it mean to be, then, American when we have these kinds of modernities meeting in the U.S.?

MS. TIPPETT: Now, you’ve written a book with a very evocative title, Globalizing the Sacred. And you and your co-author write that the genesis of the book was an apparition of the Virgin Mary in 1996 in Clearwater, Florida.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: Would you tell me about that and why that was the genesis of this lofty title?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, well, at the end of let’s put it this way: As the millennium was drawing to a close, we knew that religion was going to emerge, I think, more publicly, because people were trying to deal with this change. I mean, people try to deal with radical changes by drawing from their interpretative lenses, and religion provides the interpretative lenses for a lot of people. So we were looking for these kinds of phenomena. And the apparition of the Virgin, the Virgin appears in a bank building in Clearwater in the middle of a strip mall, this very beautiful image of the head of Mary in the window. And very soon this event becomes an event that, although started locally, it becomes globalized.

And you have the media right away sending crews to document it CNN, ABC and it begins to make the rounds on the Internet. You have people, by word of mouth, saying, ‘Well, the Virgin has appeared. And let’s go see her.’ And so pretty soon you have tourists heading to Orlando to come and see the famous apparition of the Virgin. A makeshift altar is set up there for the Virgin. And you have immigrants who are working in the nearby fields coming in to celebrate in December, thinking that this is the Virgin of Guadalupe that has appeared there because the apparition who appeared and, you know, happened in December. And so you had this polyglot group of people coming together, and for us it was a fascinating microcosm of how religion is acting today in the world. Religion is entering these very fast and very widespread means of communication

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: entering it. But at the same time, very much localized. So the global does not erase the local, but rather it is as if the local has been taken in through global media and beamed globally in such a way that now it becomes a shared space throughout the world. And so we were fascinated by this, and we said, ‘OK, so, would it be possible that religion is acting this way, not just for this particular event?’ In other words, maybe this is not just a unique event. Maybe this is indicative of the reality of religion today with globalization.

MS. TIPPETT: So, I mean, it seems kind of a paradox that in this global age, what you were saying, where we need to look for the public face of religion and perhaps its public force, is in the “little religions.” And what do you mean when you say that?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: I use that, you know, between quotes because normally

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: normally people when they think of religion they think of, you know, the great sacred books. OK? We need to look at the world religions, right?

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: And let’s go to the big temples, the mosques, the cathedrals. That’s where the, you know, real religion is happening. Or let’s look at the foundational text, the Qur’an, at the Bible. Religion’s still experienced that way, as we saw in the case of Pentecostalism where the scriptures are central, are part of the experience of the religion. However, I would have to say that there has been always this religion that has been lived extrainstitutionally, outside the canonized ways of looking at religion. These, quote, unquote, “little religions” have always been considered to be superstitious, strange, because many of them were syncretic. Many of them mixed the profane with the sacred. Many of them mixed multiple traditions.

And what I want to say is that because globalization puts us in every, you know, everybody is in everybody’s backyard, that because these localized forms of religion, these “little religions” that were practiced at the margins of the canonized spaces, writings and practices are coming to the center. They’re being recentered. And people are looking for uniqueness in a world that is more and more homogenized, because globalization also produces homogenization. People have a hunger for uniqueness, have a hunger for distinctive experiences. And I think these localized experiences provide some of that distinctiveness, and that’s how they enter these global patterns.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Scholar of religion and social change Manuel Vásquez. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, Latino migrations and the changing face of religion in the Americas.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: This is traditional marimba music from a village in Guatemala that has sent many immigrants to the town of Jupiter, Florida, where Manuel Vásquez and his colleagues are studying the role of religion. These immigrants are bringing Mayan spiritual beliefs and practices to suburban Florida. They’re seeking to preserve these even as they make a place for themselves in American life.

[Sound bite of music]

MR. VÁSQUEZ: We’re doing research on Latinos in Florida, and one of the communities that we’re looking at is this Mayan community in Jupiter, Florida. We have a very wealthy Euro-American community. People have retired from New York, from Boston, Chicago, and they’re going to Florida to enjoy the warmth. And so they have this very wealthy community called Abacoa. It’s a planned community. Everything is beautiful. Everything is in its place. But in order to take care of their gardens and golf courts and to deal with their personal needs, they are relying on a growing immigrant population coming from Guatemala. And these are Jacaltec Mayas, Mayas from Jacaltenango. And they these Mayas, basically, are sort of plopped into a very hyper-modern society with all the conveniences and all the luxuries of a modern U.S. planned city, and they are bringing their costumbres, it’s called in Spanish, their traditions of saints and spirits into this community.

MS. TIPPETT: What kind of sensibility is it? Is it Christian-influenced at all or

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, it’s a mixture of Christianity.

MS. TIPPETT: The saints it’s a mixture of Christianity and

MR. VÁSQUEZ: It’s a mixture of Christianity and

MS. TIPPETT: kind of pre-Christian?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yes. And shamanic traditions, basically.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: And what we have here is that they celebrate, they do the mass, but they also have offerings to the mountain spirits. They have offerings to their, their local spirits that are connected to their communities.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: And they literally take over the public space once a year at the beginning of February. And they have a Maya festival where they process with a saint, patron saint, and they also, and you know, wear the colorful garb of their ancestors. And they parade through the city, this very modern city, playing marimba, playing all these instruments that are kind of their local instruments. And now you have the local population coming in and sort of participating in this and saying, ‘Well isn’t this great that we have this experience of culture?’ But then at the same time, we have tensions, right?

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Because it’s OK to have a colorful festival with music and good food, ethnic manifestations that we want our community to have because, after all, we’re cosmopolitans, right? You know, we, grew up in New York, we grew up in, in Boston, and we are used to this cosmopolitanism, and we like this expression. But at the same time, we are concerned that, that our space is being colonized by someone else’s. And so we want to mark our space and say, ‘Well, wait a minute. This is our space. Why do we have these people coming in?’ You know, ‘Who are they anyway? Why do they do things this way and not that way? We do it this way.’ So globalization has this dual aspect of bringing us together, creating sort of hybrid forms of communication where people talk across languages, across boundaries, across religious traditions. But also, it has a way to really create high borders where we want to reject what’s different because what’s different is threatening.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. So in, in that sense, in terms of religion, we can think of some religious fundamentalist movements as one expression of that extreme reaction. But I wonder what you see as you study these immigrant communities and, you know, this community in Jupiter, Florida. Just let’s dwell with them. I mean, these are people who are, are disadvantaged by the structures of our society.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Right. And the structures of their society, too, where they come from.

MS. TIPPETT: And the structure of their OK, all right. Well, that’s important to remember.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah. So it’s a multiple marginality that they, that they have express.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. OK. And I mean, does religion then serve the purpose of, I don’t know, you know, let’s say, a cynic might say, ‘This is Marxist opium of the masses.’ Right? That religion kind of makes them happy in some sense and in that way keeps them in their place, gives them something to hang on to.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you also see religion in immigrant communities pushing at those structures or giving people a way to work against their disadvantages?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Well, this is an excellent question in regard to Jupiter because they not only celebrate the festival and have this one-day fiesta where Abacoa becomes Maya, becomes a Jacaltenango abroad, right? And you have people videotaping the fiesta so that they can send information back home. And you have cell phones connected so that they can hear the marimba being played in Jupiter, and they can hear it back in Jacaltenango, and the radio there, right? This is the transnationalism that that’s happening, right? And you have the mayor of Jacaltenango coming to visit Jupiter so that they have a sisterhood of cities. So you do have that.

But it’s not only a kind of one-day celebration and then they go back to their lives of being day laborers and being exploited, but also out of this organization grew a, an organization called Corn Maya, which was a civic organization that is pushing for the creation of a labor center. And the city, after a lot of struggle and a lot of debate, agreed to provide $1 million for them to create a labor center so that the Latinos who were hired would not have to stand on street corners, but they would have a more regularized space where they would be hired and they would be offered protection, and the transaction would be above board. So you see here that the religious manifestation goes hand in hand or translates into empowerment, political empowerment.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: So this organization, Corn Maya, now is a civic organization that represents the interest of Maya Jacaltec. And it’s also bringing in not just Maya Jacaltec, but also Mexicans and other Latinos who are now clustering around this organization.

(Sound bite of music)

MS. TIPPETT: Salvadoran-American scholar of religion Manuel Vásquez. He sometimes describes globalization using terms we might normally associate with physics or cosmology. For example, he says that globalization creates a time-space compression. Religion helps people unbind culture from traditional contexts and boundaries and reattach it in new time-space configurations. In his book, Globalizing the Sacred, Manuel Vásquez tells one story about Pentecostal churches and Salvadoran gangs that he titles “Saving Souls Transnationally.”

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Basically, this goes back to the immigration from El Salvador again. Because of the political situation in the 1970s and 1980s, a lot of El Salvadorans migrate to Washington, D.C., and to LA. And once they’re in LA, they have to adapt to the local culture, particularly in LA, where you had a long-standing Mexican-American culture of youth groups, you know, pachucos. The Salvadoran youth had to form their own group to protect themselves against Mexican youth or to have an identity against the other Latino youth. And so they create this gang called Mara Salvatrucha, which is a famous gang. And so they create this gang, and then with the drug trade, they begin to get criminalized.

It started as a kind of attempt to have identity for Salvadoran youth abroad, but it becomes cannibalized in a certain sense by criminal syndicates, and then it gets exported back to El Salvador. And they begin to found chapters in Guatemala and El Salvador and Mexico. And so you have these transnational networks of gangs that are operating very loosely across boundaries. And so Pentecostal churches, who are concerned very much with the youth, and our Latino population is very, is a very young population, and so if you want to minister to Latino population, you have to minister to young folks. And so the Pentecostal churches have to minister to young people who are living transnationally in these gang organizations. And so the churches themselves are transnationally organized as alternative networks of survival.

MS. TIPPETT: Between Los Angeles and El Salvador?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Between Los Angeles, El Salvador, and now there are chapters in wherever there are Salvadorans in Houston, in Washington, D.C., and you know, so it’s a whole network that’s spread. And you have churches attempting to minister at each stage of the journey of these immigrants.

MS. TIPPETT: There are some stock ways of analyzing globalization, whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Right? Or what it’s about. And on the one hand, you will have the argument that this is about, you know, economic consolidation, that it’s basically about progress.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: On the other hand, you’ll have the critique that this is another form of imperialism and that it’s about oppression. Those are forms of dialogue that tend to focus on, especially on the economic level of globalization. And I wonder, with your focus on the religious aspect obviously you’re also thinking about the economic and political

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: but how do you think that gives you a different way to interpret both the dangers and the possibilities? What do you see then that these other kinds of analysts perhaps aren’t even looking for?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Well, the focus on lived religion, focus on everyday life, you know, what these immigrants are experiencing religiously, makes you bring globalization down to earth because many of these debates about globalization are very abstract. People want to be they make these totalizing claims about what globalization is. Globalization is this or globalization is that.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: And, you know, if you make that argument, that abstract, globalization can be anything. To me, I’m interested more in the effects of globalization in its multiple ways on local life. And what I see is that these effects are paradoxical, contradictory, that it depends on who you’re focusing in at a particular time to see whether these effects are positive or negative.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Focusing on everyday life and on lived religion gives me a sense of humility when talking about globalization.

MS. TIPPETT: Earlier on, you predicted that we have sort of radical transformation ahead. And I think the numbers suggest that that’s not theoretical, that that is bound to happen just in terms of immigration and, and just the changing face of our country religiously, as, as you have studied and documented and described. You know, change is very unsettling for human beings, and it took America a long time to have a decent, humane conversation between Catholics and Protestants. And now we have this explosion of different forms and beliefs. How do you look into the future, and how do you feel about that future?

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Oh, I feel very positive about the future. I mean, I think despite the tensions and despite concerns, I would say the American experiment is alive and, and kicking. I would say, it’s basically we’re fulfilling the rhetoric that we have been talking about.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Finally, we’re becoming a pluralistic society where the issues of tolerance, of respect for human rights becomes central. And not only that, the global means of communication make it possible for us to address questions globally for the first time. So we have both pluralism and the capacity to rise above the specificity of our local concerns. Sam Huntington, a professor at Harvard University, asked a question, “Who are we?” I don’t like the answer he gives. The answer he gives is a very perfectionist

MS. TIPPETT: He’s the clash of civilization inventor. Yes.

MR. VÁSQUEZ: Yeah, the clash of civilization. The Latinos are bringing this internal clash of civilization, right? Because they bring a Catholic Hispanic culture that is more corporatist, more concerned and not used to the individual conscience, whereas our culture is more Anglo-Saxon, more Protestant, more individualistic, and you know, our language might be suffering from this. I think that take is wrong. The answer is wrong, but the question is right. I think the question is, “Who are we?” It’s a central question. In these times of globalization, where we basically are very close to each other and interacting with each other very closely, we need to ask that question, who are we as Americans? What makes us American? And, you know, at the same time that we have an identity, we also have to fulfill the promise of inclusion and pluralism that’s part of our history.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Manuel Vásquez is an associate professor of religion at the University of Florida in Gainesville. His books include Immigrant Faiths: Transforming Religious Life in America.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Many times, we can’t fit all of my conversation into the radio broadcast. Here’s your chance to hear what was cut. Go to our Web site, speakingoffaith.org, and hear my complete, unedited conversation with Manuel Vásquez. Also, download MP3s of Marie Friedmann Marquardt on transnational boomerang effects of religion and culture between, for example, a small town in Mexico and a suburb of Atlanta. We’re making it easier for you to listen to Speaking of Faith. Subscribe to our podcast, which includes downloadable audio of our radio broadcasts and many extras. Or sign up for our e-mail newsletter, which links to our audio and includes my thoughts on each week’s program. Listen to Speaking of Faith in the way that best fits your life. Discover more at speakingoffaith.org.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and associate producer Jessica Nordell. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with assistance from Randy Karels. Bill Buzenberg is our consulting editor. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections