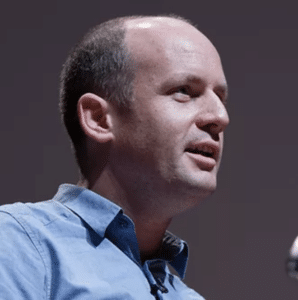

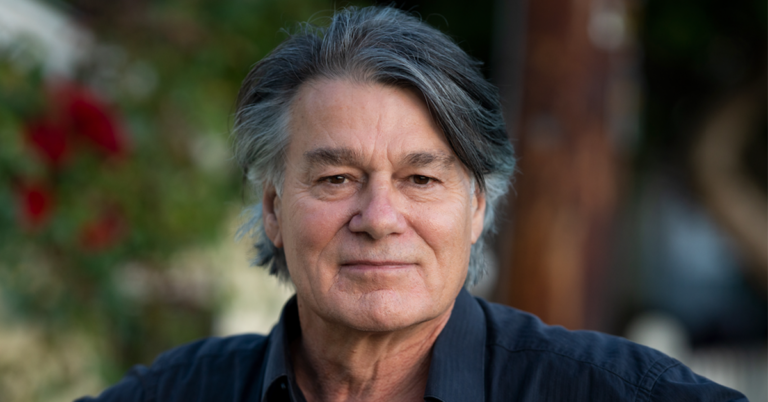

Oliver Burkeman

Time Management for Mortals

Journalist Oliver Burkeman has made a delightful and important philosophical, spiritual, and practical investigation of all that is truly at stake in what we blithely refer to as “time management.” At this time of year, many of us are making plans and resolutions — treating time as part bully, part resource — something we could fit everything we want into if only we had the discipline. This conversation is offered up to release you from that illusion. He invites us into a new relationship with time, our technologies, and the power of limits — and thus with our mortality and with life itself.

Image by Jeff Mikkelson, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Oliver Burkeman is a journalist and author. His most recent book is Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. He’s also the author of The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can't Stand Positive Thinking. He writes and publishes a twice monthly email newsletter called “The Imperfectionist.” You can find The Guardian column he wrote from 2006 to 2020 online. It’s titled, “This Column Will Change Your Life.”

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: What is time? That’s a question for philosophers and physicists, and yet it is also an element by which each and every one of us experiences and orders our days and our lives. At this time of year, many of us are making plans and resolutions, treating time as we’ve been taught: as part taskmaster, part resource — something we could fit everything we want into, if only we had the discipline. In his longtime column for The Guardian, and books with subtitles like Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking, my guest Oliver Burkeman has long interrogated the possibilities for absurdity in self-help while also honoring the real and deep human longings it meets. And he himself became a time management and productivity “geek,” until one day, sitting on a bench in Brooklyn, he grasped that no one achieves perfect work–life balance — that in the end, even the most privileged of us rarely get around to doing the most important things.

Where he went next is the conversation I have with him this hour: deep into a philosophical, spiritual, and practical investigation of all that is truly at stake in what we blithely refer to as “time management.” This conversation extends an invitation to nothing less than a new relationship with time and our technologies and the power of limits — and thus with our mortality and with life itself.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[“Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Oliver Burkeman’s newest book is Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. He grew up in northern England. He was raised, as he says, “non-spiritual” Quaker, on one side of his family, and also has a Jewish lineage with a background of narrow escape from the Holocaust. In terms of his early formation around time, he says he relates to an Onion article with the headline: “Dad Suggests Arriving At Airport 14 Hours Early.”

Well, I feel like Time Management is a very — is almost a misleading title for this book [laughs] that you’ve written, because it really is about great, existential questions of meaning. Do you think that emerged from that early life? Where did that come from, or when, how did that start emerging?

Oliver Burkeman: Well, a long time ago when I was still at school, I started to be the kind of person who was always looking around for systems of organizing my time. And I was always the person with the really beautifully designed exam-preparation timetables — whether I actually was any good at the exam preparation is a separate question, but, you know, the person with the multi-colored felt tip pens and all the rest of that. And I sort of, I think this — my more recent work and most recent book is sort of about the disillusionment with this kind of attempt to neatly organize and control time and life. But the sort of more naïve attempt to just do it goes back with me a very long way.

And then I ended up writing this column for The Guardian for so many years that it was sort of with me —

Tippett: Yeah, which is how I first found you.

Burkeman: Right. Right. It was sort of with me while I changed [laughs] in all sorts of ways, and in many ways I think it was kind of public — weekly therapy in public, in a way. And I sort of went from one kind of person, with respect to these kinds of issues, and ended up another one at the other end.

Tippett: Remind me the title? The title of the column?

Burkeman: It was called “This Column Will Change Your Life.”

Tippett: Yeah, right. [laughs] Right.

Burkeman: I spent a lot of time explaining to people that this was meant to be sardonic and not incredibly grandiose.

Tippett: But you also were writing, you were bringing it into the world in a time in which people started looking for things that promised to change your life, I think with a new fervor, or at least, a new openness about it.

Burkeman: Yeah, I think that’s right. I think that’s right. I mean, definitely I was sort of backing into these topics. Partly this might be a Quaker-y thing; I think it’s definitely a British thing, maybe a male thing to be kind of uneasy writing about happiness and the reverse of, the opposite of happiness, and questions of meaning that can seem sort of embarrassing for a range of reasons, I think. And so I was sort of backing into it by writing about it in a sardonic fashion — hopefully not a hugely cynical one, but in a way, [laughs] losing my cynicism about it was what marks the experience of writing it for so many years — becoming more sincere.

Tippett: Yeah, and here we are. You’ve written a very sincere book.

I’m just curious about — if I ask you, What is time?, how do you start to answer that question now, after having delved into this?

Burkeman: Oh, I definitely know much less [laughs] what the answer is now than when I started. But it’s one of those things that it’s incredibly difficult to pin down once you really focus or try to focus precisely on it. And so yeah, we, as you say, we fall immediately into these kind of resource terminology, this idea that it’s something we have and can use well or use badly, make better use of, sell to somebody, buy from somebody.

And that is true so far as it goes, but then you run up against all sorts of ways in which you’re taking that approach to something that actually isn’t really a resource in the same way that money or raw materials is a resource. And we sort of — I, anyway, think about time in a spatial metaphor, so the sense of whether I have enough time to get to the end of my to-do list by the end of this week, that’s to do with fitting objects inside a container, somehow. And none of this is actually [laughs] what time is, right? We don’t have it — I don’t have five hours to get through my work at a given period, I just have this one moment, and anything could happen in the next one.

Tippett: Yeah, we think of it as compartments, and they move, and it goes forward, which is what Einstein said it doesn’t work that way. What you explore and just name is that so many premises that we kind of just accept, collectively, and structure not just organizational life or institutional life but in our life, our personal lives — these premises just don’t hold up to the truth of reality. And so, for example, that if we only managed our time correctly, we could get everything done that we want to get done — [laughs] like, this notion that we could get “on top of things.” And this is where, you know, you walk into time management, but you actually unfold that this is about the meaning of our lives. This is about the big, existential questions. And you write about this feeling that goes deep, “the sense that despite all this activity, even the relatively privileged among us rarely get around to doing the right things.”

Burkeman: I was just really intrigued, the more that I managed to get some distance on my own odd and neurotic approaches to trying to manage my time — and definitely saw it in other people, and read accounts of it — that this effort to achieve mastery, this effort to sort of reach the state of feeling controlling and secure with respect to time, it’s not just that it doesn’t work, it’s that it seems to do the opposite of working. It seems to push the things that matter the most further and further over the horizon.

So the really sort of mundane example I give in the book is just that when I was in my early days as a newspaper writer, the better I got at processing tasks and getting through those lists, the more prone I was to postponing the things that really, really mattered, because I would fall into this notion of, this idea that I needed lots of spare time and attention and focus to really do those things well, and that in the meantime, the diligent thing to do was to get rid of all these little, less important tasks that were tugging at my attention; to, you know, “clear the decks.”

Tippett: Clear the decks so we can do the things —

Burkeman: I think this is a really deep and important metaphor, this idea of “clear the decks.” [laughs] And so, yeah, I think that you can spend a lifetime “clearing the decks,” because actually what happens is they’re never clear, and the act of clearing them causes them to fill up again faster, for various reasons. And that way, you can just never get around to the things that you know or believe are the most important things. And I began, slowly and late, to notice that that [laughs] was exactly what was happening in my life.

Tippett: And I think, you know, some of the truths you tell are just kind of, again, articulating that what we actually know about life is that it’s the things — that our lives are as much made by the things we couldn’t plan for, didn’t see coming, that surprised us — maybe almost completely made up of that. But I think something that you say that really, really is settling in me is that in order to, let’s not say “manage” our time, but in order to live fully and kind of in a more gracious way with time, we actually have to forgo not just things that we don’t want to do — it’s not just saying, like, OK, I won’t clear my inbox every day, which I do, which is a real problem in my life, right? It’s that I won’t say that — it’s not that I get to say that, that I just won’t do this thing that I know is stressful but I do it. It’s that we’re going to have to forgo things that we’d actually like to do, because you have to make choices about what matters.

Burkeman: Yeah, and that you already are making those choices, right? We already are …

Tippett: [laughs] We are making those choices.

Burkeman: … condemned to choose, as the existentialists say. It’s just that we can choose whether to do that consciously or not.

Right: there’s something in me that persists in thinking that there must be some way to spend as much time as I’d like to writing, connecting with people, with my young son, in personal reflection and meditation, you know. But there’s no reason why that should be the case. [laughs] So you do have to go through some kind of a defeat or a surrender. You see what is off the table for you, in your life, which is ever getting to that sense of really feeling that you did everything that was legitimately calling for your attention.

[music: “Coulis Coulis” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with journalist Oliver Burkeman.

[music: “Coulis Coulis” by Blue Dot Sessions]

This idea of time and how we use it, what it is, how we use it, it also really ends up being a way into what is a deep spiritual truth at the heart of all the great traditions, and also just the psychology behind them: that what we pay attention to — and also just our understanding of the mind, which is increasingly sophisticated — that what we pay attention to defines us and defines reality for us. And this approach to these questions, then, it kind of shines a different — it’s an interesting nuance of the light that we shine on how the digital worlds — what the digital world as part of human life — how the digital world kind of ratchets up these bedrock dilemmas that we’re talking about, in an existential way; I mean, just even the language of the “attention economy” or

“persuasive design,” which you talk about in this context. I wonder if you would just — and of course, these are phrases I’ve heard before, but I feel like you are opening them up in such an interesting new way in this.

Burkeman: I mean, there were two points I felt I really wanted to try to make about attention, beyond that one that it just, you know, it is what our life consists of. And one of them, yes, was then how central this question of attention-mining technologies are.

But the point that really I think is so important, there, is that this doesn’t just take your attention for the time that you’re using it, right? This is what I really began to notice when I got most deeply into social media, is that it wouldn’t just be the hour that you whiled away on a social media platform that was changed by that hour, but then, like, three hours later I’d be making dinner or at the gym or something, and in my mind I would be prosecuting arguments against these incredible idiots whose views I’d had to be exposed to earlier in the day. And I mean, that’s a strange way to be, [laughs] firstly because it obviously is changing what my attention is on for much longer than that initial hour, and then, secondly, because these people — I mean, they probably don’t know I exist at all, in most cases, that I’m in a sort of state of fury about.

Tippett: Also, you wrote this interesting piece in The Guardian about a certain mindset that has taken hold in this world of limitless media, that so many people feel — that there’s this — you know, there used to be this kind of duty of the citizen to be informed. That’s an idea that’s been around a long time. But that was also in a world of scarcity and not limitlessness, where you had to do some work to find the news and it wasn’t constantly being [laughs] refreshed every five minutes. And you said that that has shifted, and again, that we haven’t been necessarily — this hasn’t been necessarily a conscious, intentional, self-aware shift, and certainly not thinking about the consequences of not just a duty to be informed, but a duty to not turn away from all the information that’s out there and, you say, the belief that we’re “morally obliged” to stay plugged in.

Burkeman: I really started to notice this just a few years ago, I guess, it was four or five years ago, the way that more and more people I knew, and certainly people I observed on social media and, to some extent, myself — they’d sort of shifted the center of gravity. You had the sense that they saw themselves as primarily existing sort of in the news cycle. And then things like what they did in their house, and their family or where they worked and the street they lived on, were kind of somehow secondary and that they sort of fundamentally lived in the drama of the news.

And I think part of the reason for that is that these attentional technologies give us a feeling of acting on it. Even just scrolling is more active than watching a TV bulletin. And commenting and retweeting and all the rest of it is obviously significantly more active. And so there’s this feeling that you’re somehow doing your bit —

Tippett: You’re participating.

Burkeman: Right. Absolutely. It’s especially difficult because probably nobody who is spending their whole day distracted by celebrity gossip is under any illusions that this is somehow some high duty of citizenship in a democracy that they’re performing. But I think you very easily can think that when the substance is the drama of national and international news. But because there is so much more of it than our attention could ever take up, it might be the case you have to sort of proactively not care about a huge number of very important issues in the world just so that you can meaningfully care about one or two of them. It might be that you have to do that just in order to consolidate your efficacy.

Tippett: And that gets back to that point that each and every one of us, to do what we actually mean idealistically, when we say “manage” time, structure our lives in a meaningful way, not merely a productive way. We’re going to have to not do a lot of things that we would like to do, in order to really invest and really be present to the things that are going to make our lives worth living and that we are — I don’t know, I use this language — that we are specifically called to, either by where we are or who we are, what our gifts are, or just the place we find ourselves in and its needs.

Burkeman: Yeah, I think that it entails this ability to sort of tolerate a kind of anxiety that is built into that situation, right, that actually dissipates a bit if you are willing to tolerate it, but that is this uneasiness of knowing that you are neglecting things, that there are people and causes and work projects that have an absolutely legitimate claim on your attention and are not going to get it. It’s not easy, especially if you have got any form of kind of people-pleasing motivation in you, or conflict aversion, which I most certainly have. [laughs] It’s — yeah, you have to sort of pick a fight with the world, in a way, at least, in order to focus meaningfully on a few things.

[music: “Secret Pocketbook” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Oliver Burkeman.

[music: “Secret Pocketbook” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today exploring our relationship to time as a relationship to life itself, and all the implications that has for what we call “time management” — how we navigate our lives with technology, for example, and the deep importance of limits, as much as of possibility.

You know, something else that’s involved in all of this that is also just about the strange human condition is, as you said, sure, there are a thousand people creating that — what is it called? — persuasive design, for my attention, on the other end of my devices. But on the other hand, you know, I know some of those people, and they’re not all evil, and the truth is that one of the strange things about us is that we are, we are so distractible, right? It’s not just — I think you say this — it’s not just that we submit to distraction, we throw ourselves at it so readily. There’s this mystery that is true, I think, of all of us — I don’t know, if people listen to my show and they think that I sit around thinking big, deep thoughts all the time and only reading books about the meaning of life, and don’t know how many, you know, [laughs] how many murder mysteries I read — that we’re all, we are uncomfortable — you say this — we are uncomfortable turning to what matters. And so it’s that collusion, right, it’s that collaboration, that collusion with this aspect of the human condition.

Burkeman: Mary Oliver has this lovely phrase, “the intimate interrupter,” to refer to this trait inside us that wants us to do anything apart from the thing that five minutes ago, we knew was the thing that needed our attention and our care. It is mysterious. But I think it can be explained. It’s not a coincidence that the things that matter trigger these feelings that we’d rather run away from into the pleasing and numbing and comfortable world of distraction, right? I mean, it — they bring us up against our edge. When I sit down to do a piece of writing, the stakes are high, because I care about it and I want it to be good, and I have no control over whether I’m going to prove up to it or whether other people are going to receive it well, so I’m in this familiar human situation of really caring that things turn out a certain way and realizing that I don’t get to say whether they will. And you can, by analogy, you can see how that would be true of a difficult conversation with a partner, say. It’s really important, but it might turn into a big argument and a fight, or it might just leave me feeling emotionally vulnerable, and, you know, and it really matters. So things that matter bring us to our limits.

And it actually changes that one of the sort of breakthroughs for me, in thinking about my own personal struggles with distraction, it’s not the case that you’re trying to have a conversation with your spouse, say, and listen to what they’re saying, but you’re distracted by your phone that you’re actually scrolling through under the dinner table where no one can see. It’s that scrolling through your phone under the dinner table where no one can see is what you do to avoid the discomfort of listening and of the conversation. And, like, nothing is harder than listening, I think. So it’s flipped. It’s not that you want to do one thing, and the nasty technology is taking you away from it.

Tippett: And your phone is getting in the way.

Burkeman: No, it’s a sort of eminently forgivable and understandable but ultimately kind of weak-willed respite from doing what matters in that moment.

Tippett: It’s hard to think of anything worth doing that doesn’t take kind of effort and patience and that spirit of surrender. And that’s uncomfortable. Those things can be really uncomfortable.

Burkeman: I think boredom is a really [laughs] fascinating part of this, if that’s not just …

Tippett: Say some more.

Burkeman: … too contradictory. I mean, it’s always really struck me how aggressive the feeling of boredom, or what we call boredom, but it’s really sort of a — it’s a real, kind of serious struggle with reality just implacably doing its thing, regardless of how much freer you’d like to feel, I think, I mean, if that makes any sense.

Tippett: I will say I notice in myself, and I worry about younger generations, although I think they will have resources that I don’t have to rise to this, that, you know, how easy it is to go down a rabbit hole to fill — there’s a phrase, “fill time,” [laughs] which wasn’t available for most of my life. You know, when standing in a line, you were standing in a line. That was it. Maybe you had somebody to talk to. Or you were at the park with the kids. You didn’t have your phone to keep you busy or keep you entertained.

Burkeman: I have a completely untested theory that impatience in all sorts of physical settings, like people honking their horns angrily in traffic and people getting furious waiting in line, gets worse when those same people are accustomed to not having to wait two seconds for the app to call up the song that they just thought of that they’d like to listen to, or one second to find out what’s happening in the world, thousands of miles away. It makes all the remaining ways in which we don’t get to set the pace of reality all the more, kind of, insulting.

I think that the closer technology brings us to the cusp of feeling like we are the gods of our time, the more incredibly offensive it seems [laughs] to be reminded of all the ways in which we still aren’t. So, you know, you get this utterly bizarre situation where the world speeds up and gets more and more efficient, and we have all this technology for saving time, and it doesn’t make time feel more abundant. It makes us feel more impatient, which, on the face of it, should not be the case.

Tippett: So I’m really curious about how all of this — you know, this research and thinking and crafting and pondering these ideas, how — what are the ways that you live differently, or try to live differently? I mean, you also have young children. Does it become more natural if you try — what changes? What’s changed, for you?

Burkeman: This topic is compelling to me because I was, and to a significant extent remain, someone who felt like I needed to get on top of everything, otherwise absolutely terrible things would happen; who felt that if I didn’t get to the end of a day having been productive to a certain level that I never seemed to reach, that I hadn’t quite justified my existence …

Tippett: Existence, yeah.

Burkeman: … on Earth. And I totally recognize that in myself still, today, but — well, firstly, I think recognizing it is a very big difference. It’s not that I won’t ever get into the sort of frenetic, hamster wheel mode of, I’m going to work really, really hard and put all the rest of my life on hold, and in a week I’m going to finally have reached the serene paradise of being in touch with and on top of everything. I mean, I can fall into that, but I can see that I’m falling into it and thus usually back away from it.

And yeah, I think it — the moments for me where it feels different, although still a struggle, are in those transitional times in the course of a day, right? It’s getting up from my desk and switching into full-on parenting mode and seeing whether I, how much I’m able to sort of not carry a residue of: Oh, but I was almost there, you know? I had almost completely, you know, reached the position of perfect productivity and time mastery in my work, and now I have to leave it to go and do this?

I mean, that’s the bad days. The good days are, I’ve done a few important things that matter, it was always off the table from the beginning that I would ever get to the end of all the things that matter, and now I can go and do some things that matter in the family realm.

I am definitely a bit more at peace with those things because I no longer believe, deep down, that I’m going to one day get to the point where you’ve reached the summit and then you can just keep walking along the plateau with no effort; that you’re going to reach the top part of life, where there are no problems. Whoever had the — it’s such a ridiculous idea, [laughs] but very, very alluring.

[music: “Spring Rain” by Auditory Canvas]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with journalist Oliver Burkeman.

[music: “Spring Rain” by Auditory Canvas]

You also, at regular intervals in the writing, you will stop and say, This is a relief. It’s a relief to know that there will be neglected, missed opportunities, that there will be losses, that it is in the nature of vitality that there is loss. And part of this time management mentality that we have is that somehow you can salvage it all, that you can somehow make it all possible and not have to sacrifice anything. But you say this is a liberation.

Burkeman: I really believe this. Firstly, just an incredible relief in seeing that something you had been trying to do and that you thought your sense of self-worth was dependent upon was sort of structurally impossible, logically impossible, not that you just hadn’t quite found enough self-discipline or the right techniques or that you were uniquely kind of useless compared to all the good people, but that it’s just not part of the human gift, [laughs] to be able to reach this kind of position of sort of control and security with respect to time. So that’s just a relief, because you can stop or ease up on beating yourself up about something that nobody could be expected to do.

Tippett: And you also have this wonderful — this notion of kind of the relief of understanding our cosmic insignificance. [laughs] Say something about that and why that is freeing.

Burkeman: This may to some extent say unflattering things about me, but I think I’m not alone. A big part of the stress that comes with the deepest questions of what I insist on calling “time management” — you know, deciding how to use our allotment of time on Earth — comes from a kind of egocentric focus, really; an idea that it is incredibly important, even on the level of the universe — although we probably wouldn’t endorse that explicitly, I think it’s sort of there in the emotional pull — that what we decide and whether we make the right decisions and spend our lives in the right way, that it really, really, really matters. There’s something incredibly, again, liberating in understanding a little bit more about like, just how tiny each of us is in the scheme of things.

I think the other thing that this does is it sort of reconfigures the definition of what it is to live a meaningful life, right? Obviously, one way you can go with that is into nihilism, and say like, well, there’s no point in anything.

Tippett: Then it doesn’t matter at all.

Burkeman: Right. But the other way of thinking about that, I think — and I’m working partly, here, off the work of the philosopher Iddo Landau — is to say, why use this definition of meaning that has to have cosmic significance? Why burden ourselves with this kind of cruel standard that means that all sorts of things that I think we instinctively know are meaningful is a stupid way to spend your life? And it’s obviously — the problem here, I think, is the definition rather than the activities. So I think there’s really something to be said for seeing that.

Tippett: I just want to read some of the lines from Four Thousand Weeks. And just — I don’t think we said this at the beginning. Four thousand weeks is the length of a life, right?

Burkeman: Very approximately.

Tippett: Very approximately.

Burkeman: I went for the headline-grabbing figure, but yes.

Tippett: But it sounds — I mean, to put it in that kind of finite term, that’s so interesting, how that just kind of shifts your imagination, to think about — rather than — 4,000 weeks, instead of years and …

Burkeman: I think that, you know, we don’t get many years of life. But they seem to last for a long time. So it’s — in a way, it’s kind of fine. And we get a huge number of days, so it doesn’t really matter, we tell ourselves, that we can easily waste them. But weeks is a very strange way of putting it, and I think it — that’s why I’m drawn to it, you know, because …

Tippett: It doesn’t feel like a lot.

Burkeman: … you don’t get very many …

Tippett: No.

Burkeman: … but it’s really easy to waste a whole one without really …

Tippett: [laughs] That’s right!

Burkeman: … or to wonder where the whole last six of them went, or something like that.

Tippett: So I want to read something that you wrote. So “No wonder it comes as a relief to be reminded of your insignificance. It’s the feeling of realizing that you’d been holding yourself all this time to standards you couldn’t reasonably be expected to meet. And this realization isn’t merely calming, but liberating, because once you’re no longer burdened by such an unrealistic definition of a life well spent, you’re free to consider the possibility that many more things than you’d previously imagined might qualify as meaningful ways to use your finite time. You’re freed, too, to consider the possibility that many of the things you’re already doing with it are more meaningful than you’d supposed and that until now, you’d subconsciously been devaluing them on the grounds that they weren’t ‘significant’ enough. From this new perspective, it becomes possible to see that preparing nutritious meals for your children might matter as much as anything could ever matter, even if you won’t be winning any cooking awards, or that your novel’s worth writing if it moves or entertains a handful of your contemporaries, even though you know you’re no Tolstoy, or that virtually any career might be a worthwhile way to spend a working life, if it makes things slightly better for those it serves.”

It’s lovely.

Burkeman: [laughs] Thank you. I’m tempted to say, “I couldn’t have put it any better myself.” [laughs]

Tippett: OK, yeah, excellent. [laughs]

I have this thought experiment that I play, that I’ve played for a long time, and it’s always on my mind right now because we live in this time where everything feels existential. And so let’s say our species survives and our descendants look back, or a historian looks back at our moment 100 years from now, like, what will they see? And

it may just be what we were doing or failing to do, in terms of owning our footprint on the planet. It might just be refugees, you know? I’m curious if you — and you’ve written a lot about conscious — you’ve written some wonderful things about consciousness as one of the things we’re grappling with. I mean, I wonder is this something that you think about, or if I ask you what fascinates you about what might be happening now that we barely heed or pay attention to that might be what is seen when time becomes history?

Burkeman: I really love this, I guess it’s a thought experiment, that the philosopher Bryan Magee used that I mention in the book, where if you sort of imagine a chain of centenarian lives through history —

Tippett: Oh yes. Yeah.

Burkeman: All the way through history, there have been some people who lived to 100, even when life expectancy was much shorter on average. And every day that somebody turned 100, there was a baby being born somewhere. So you could easily imagine these chains of end-to-end, 100-year lives. And if you do it that way, you find that, like, the Renaissance was what, six, seven lifetimes ago, and the time of Jesus about 20 or so lifetimes ago, and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs, 35 lifetimes ago, and the whole of human civilization, based on a conventional definition, 60 lifetimes ago. It’s like, it’s nothing.

Tippett: Nothing.

Burkeman: And yet we think of these kind of “periods,” right? It’s like, Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, as if they are these kind of huge, glacial periods. And, well, firstly, I think that’s just fascinating because it shows how quick everything has, how fast everything has happened and how what gets retained from each of those periods feels like these kind of huge, timeless, or huge, slow-moving changes, and would mean very little to the people who lived in them.

Tippett: Almost like it’s completely alien to us, right — disconnected from us entirely.

Burkeman: Right. And yet, as others have pointed out, this will be a period, as well. Like, what we are doing now will be characterized by some basic, single notion, [laughs] like the Renaissance or the Enlightenment or the Dark Ages or whatever.

As to what that will be, I mean, what this is the era of, I just — I don’t even know how to go about starting to think about that, that question, for the reasons that you say. I mean, it’s like, the perspective doesn’t seem takeable from now. I think the sort of not-knowing is interesting here. And I use this metaphor, this idea that we’re all in the position of stonemasons working on a cathedral of the kind that, like in my hometown of York, that would’ve taken hundreds of years to build. Most of the people who worked on that would have had no expectation of being there for the opening day, you know? It just wasn’t the — that wasn’t the point. You’re just placing a brick, [laughs] and another one and another one, and having no expectation of knowing where it’s heading. And I think we’re all in that situation anyway, it’s just a question of whether we sort of face up to it or not. [laughs]

Tippett: Yeah, we don’t — well, some of us don’t think so, but we are.

You have this phrase, which I think you credit a Swiss psychologist and scholar of fairy tales, Marie-Louise von Franz — I’ll just read this. She said, “There is a strange attitude and feeling that one is not yet in real life. For the time being, one is doing this or that, but whether it is a relationship with a woman or a job, it is not yet what is really wanted. And there is always the fantasy that sometime in the future, the real thing will come about. The one thing dreaded throughout by such a type of man” — I think, speaking as a woman, that can happen to us, too — “is to be bound to anything whatever. There is a terrific fear of being pinned down, of entering space and time completely, and of being the unique human that one is.” That phrase — really, that’s what we’re talking about this whole conversation, right: “entering space and time completely.” [laughs]

Burkeman: Yeah, I love that passage. And this notion that it’s going to be later that we have things together, and really there’ll be a moment of truth, and that’s when we’re going to sort of enter into things, and — it’s already not true. We’re already …

Tippett: [laughs] In it, yeah.

Burkeman: … as here as we’re ever going to be. But there is that shift that comes from — I almost want to say “resigning yourself” to that fact. [laughs] There is a sort of inner entering into it that you can choose to do or not do. And life just sort of feels a bit like a dress rehearsal, until you do.

Tippett: Here’s something you write, also. “Those moments life shows its imperfection, brokenness, resistance to our plans” — and this is, again, just this core observation of wisdom, of spiritual depth — “such experiences, however welcome, often appear to leave those who undergo them in a new and more honest relationship with time.” And then you say — and this is what I think the challenge for our species is — “The challenge is whether we might attain at least a little of that same outlook before agonizing loss comes our way.” Can we grow up enough to make that move, without needing to be in a state of utter despair and burnout, I think is the question.

Burkeman: Yeah, and it’s parallel, isn’t it, to that question of can we hold onto epiphanies from this pandemic period, realizations and shifts in perspective? Can we hold onto these ways of seeing the world, once life stumbles back towards something like normal and we’re not in that crisis? And maybe plenty of people on a personal level will not have gone through a severe crisis, so those perspective shifts will have been had without agonizing loss, for at least some. Or do these epiphanies and these realizations just fade unless you’ve really, personally suffered? I don’t know. Yes, we’ve got to try.

Tippett: Yeah, that gets back to we have to train our attention on it, right? We have to decide to attend to it and know that we will be distracted anyway, right?

Burkeman: Right, and just to sort of — I don’t know. In my own, I feel like the thing that I can easily ask of myself, and therefore maybe of other people, too, is to just sort of keep pushing forward into that mild discomfort. Obviously, the passage you read comes after writing about people who’ve gone through tragedies that the word “discomfort” isn’t appropriate. But the very mild discomfort that our finitude creates in us is just the discomfort of writing this next paragraph that I’m working on instead of going to social media, listening to what the other person is saying instead of just rehearsing what I’m going to say as soon as they’ve finished talking — just that mild discomfort. It’s the same discomfort, I argue, but in an incredibly mild form, and it is actually doable. Like, you can actually do that, and you’ll be fine. You can do it multiple times a day, and you’ll be fine every time.

Tippett: So I’m curious, this question of what it means to be human is obviously a very large question, and — but I’m curious about how this exploration of the nature of time has — how has it evolved your sense of what it means to be human? I mean, how, right now, would you just start to answer that question, in this light?

Burkeman: Wow, it’s a big one. I think it is that appreciation for the way in which everything sort of worth doing, everything creative or generative or growth-oriented, all the rest of it, that loss is kind of the inevitable flipside of that. So it’s that sort of — it’s that duality of experience that, you know, it’s most obvious in the case of parenting, where it’s almost a cliché, right? Every new, extraordinary thing that a small child does is the end of the time before that time. But it occurs in everything, all through the day and all through one’s work, all through everything, that to do anything is to forgo all sorts of other things. And this isn’t some recipe for making the pain go away, but I experience a sort of amazing drop of my shoulders and all the rest of that whenever I can recall that this is just built in. This is like, how it is. This is not because I didn’t find the sneaky way out of it yet.

And if you sort of do this a little bit more, it starts to sort of justify itself as a way of living because you do sort of have a little bit more faith in things unfolding, and then you do it for a few days, and you find that things just carried on unfolding and it was OK, and then you can sort of ease your way into it. And I definitely have done that. Of course, it’s two steps forward and one step back, as those I live with would doubtless testify. [laughs]

[music: “Awakening” by Random Forest]

Tippett: Oliver Burkeman’s most recent book is Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. He’s also the author of The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking. He also writes and publishes a twice monthly email newsletter called “The Imperfectionist.” And you can find the excellent Guardian column he wrote from 2006 to 2020 online. It’s titled, “This Column Will Change Your Life.”

[music: “Awakening” by Random Forest]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections