Rev. Otis Moss III

The Sound of the Genuine: Traversing 2020 with ‘the Mystic of the Movement’ Howard Thurman

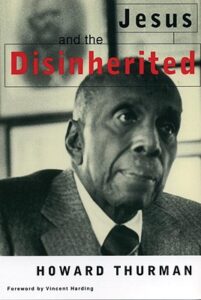

An hour to sit with, and be filled. Two voices — one from the last century, one from ours — who inspire inward contemplation as an essential part of meeting the challenges in the world. Howard Thurman’s book Jesus and the Disinherited, it was said, was carried by Martin Luther King Jr. alongside the Bible and the U.S. Constitution. Thurman is remembered as a philosopher and theologian, a moral anchor, a contemplative, a prophet, and pastor to the civil rights leaders. Rev. Otis Moss III, himself the son of one of those leaders, is a bridge to Thurman’s resonance in the present day, and between the Black freedom movements then and now.

Image by Sarah Yenesel/Sarah Yenesel, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Otis Moss III is senior pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago and the author of several books. He led the team that developed the “My Life Matters” curriculum, which includes the video, “Get Home Safely: 10 Rules of Survival.”

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Howard Thurman is one of the most influential philosophers and spiritual teachers of the 20th century, and his influence is rising again for new generations. It was said that Martin Luther King Jr., carried Thurman’s book Jesus and the Disinherited alongside the Bible and the Constitution. Thurman insisted on a place for spiritual nurture at the heart of social activism, and he brought a searching theology of Jesus to that. He was, at the same time meditating in the early 20th century — traveling to India, bringing the teachings of Gandhi and Thich Nhat Hanh to the civil rights leaders, even influencing Jewish mysticism. Today we bring Howard Thurman’s wisdom forward, exploring its resonance in the theology and life of a religious leader in the year 2020: Otis Moss III. He is a theological but also a literal bridge between Howard Thurman, the Black freedom movements of the last century and of ours.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Howard Thurman was born in 1899 and died in 1981 in San Francisco, where he co-founded the first fully intentional cross-racial church in the U.S. Otis Moss III was born in 1970 and grew up with legendary civil rights figures in and out of his family home, from Fannie Lou Hamer to Andrew Young. His parents were married by Martin Luther King Jr. His father, Otis Moss Jr., was an influential pastor and civil rights leader based in Cleveland. Today Otis Moss III is himself a senior pastor of the influential Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago.

Tippett: Do people call you “Pastor Moss”? What do people in your congregation call you? I’m just curious.

Rev. Otis Moss III: Some say “Pastor Moss,” “Pastor O” … [laughs]

Tippett: I probably won’t call you “Pastor O” on the air, but I like knowing that.

Moss: “Reverend O.M. Three” — these are all kind of names, you know. “Otis” …

Tippett: But “Pastor Moss” would be ..

Moss: That’s fine

Tippett: So you have said that Howard Thurman is one of the most influential theologians — and, I think, one of the most underappreciated. And I agree with you; I feel like he’s a voice — and not just a voice, but an element of the civil rights movement that’s kind of hidden from history. So we’re not partaking of the whole lineage, in some ways. And so what we want to do with this show is introduce him to a wider audience. And so, I have my copy of the sacred text, Jesus and the Disinherited, with me.

Moss: Yes. Yes, yes, yes, yes.

Tippett: And so [laughs] I may read some passages. I will say, just starting out, I like, amidst all of the official facts of your bio — being the pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, studying at Morehouse College and Yale and Chicago Theological Seminary — you also note that you’ve been highly influenced by the works of Zora Neale Hurston, August Wilson, Howard Thurman, jazz, and hip-hop music. [laughs]

Moss: Absolutely. Without a doubt.

Tippett: And that’s in your official bio.

Did you meet Howard Thurman?

Moss: I never met Howard Thurman. But I heard his voice often in my household. My father has this incredible collection of Thurman tapes, and he gave that collection to Morehouse to create the Howard Thurman Listening Room.

Tippett: Oh, and probably you’re talking, really, cassette tapes.

Moss: [laughs] They are tapes. [laughs] They are tapes. And when we would go on trips when I was very small, we would drive — for vacation, we would hop in the car and go on vacation. And my father would play Thurman tapes part of the journey. We had some music that we wanted to hear, but we would listen to Thurman, also. And so I became familiar with his voice before I really knew who he truly was.

Tippett: If I ask you now — and you may have been conscious of this or not as conscious — how his theology, his religious sensibility — how did that imprint the religious sensibility that you started to inherit and imbibe in your childhood?

Moss: I have to tell this story. So I was probably about eleven or twelve. And Andrew Young came to preach, and Andrew Young loved engaging with young people. And after service, he would talk with all the young people at church. And when we went back to my father’s office, I was minding my own business, being a P.K., just wanting to go home, [laughs] as P.K.’s do.

Tippett: Preacher’s kid, we need to say that for people. I’m a preacher’s granddaughter, so I know what it is, too.

Moss: For those of you who don’t know, preacher’s kid, it’s a life. It’s a unique culture. It is a fraternal sorority that you are pledged into.

And I was minding my own business because I wanted to go home, be with my friends, all of that. I’d been in church too long. So he engages me, and he says, “Otis, have you read Howard Thurman?” I was like, “No, I’m eleven. No, I haven’t read Howard Thurman.” [laughs] And so he looks at me. He says, “I want you to go and get your father’s copy of Jesus and the Disinherited. I want you to read it. And I want you to call me when you’re finished.” And this is Andrew Young talking to me. I’m like, “Oh, OK, sir.” So I went home. I never finished the book, but I read the first few pages. And it stuck with me, this idea of looking at Jesus through the lens of those who are disinherited. And the imprint of his grandmother on Thurman never left me. So that framework of Jesus as being this radical, revolutionary, nonviolent person who was on the margins always was a part of my theology, and not an exclusive Jesus, but one who was just, for lack of a better phrase, he was just down for the people.

And that was the Jesus that I always saw. I never saw the one that was on TV, the hippie Jesus. The Jesus that I was introduced to was the one who not only was at Calvary but was also at Montgomery.

Tippett: Well, there’s a lot to start with there. I’m just gonna read the first sentence of Jesus and the Disinherited. “Many and varied are the interpretations dealing with the teachings and the life of Jesus of Nazareth. But few of these interpretations deal with what the teachings and the life of Jesus have to say to those who stand, at a moment in human history, with their backs against the wall.”

That phrase is just — so tell me. Let me just ask you the question, who do you understand Jesus was for Howard Thurman, and also, how does that relate to who Jesus is for you?

Moss: For Thurman, Jesus was this human being who was so deeply, divinely connected, at a level that no other human being in history has ever been. So his Christology does not fit into the highly traditional Christology of just divine and human. He saw them as divine and human, but as a mystic, he leaned on the human side and allowed the echo of the divine side to encircle his interpretation of Jesus.

Tippett: You called him a mystic. And it feels to me like in some ways he was so ahead of his time. It’s interesting to me — you were part of this documentary about Howard Thurman. And I noted down all the different ways people described what he was, like what was his role. And here are all these different ways: pastor to the leaders; moral anchor for the movement; had an established philosophical framework; teacher; spiritual activist; mystic; contemplative spirituality; nature mystic; talking to trees — this is where he was very much ahead of his time; saint for the movement. And I think, to me, even what you just said, I think it would be surprising to people who have a basic “what you learned in history about the civil rights movement,” to know that it had a mystic who was the pastor to the leaders and the teachers and the activists.

Moss: It’s fascinating that so many people who were part of the movement have these unique Howard Thurman stories. Of course, Dr. King made these connections with Thurman. The SNCC community [laughs] had this connection with Thurman. And Thurman was always pushing them on the inward journey, on who they are and their encounter and to find — in his words, find “the sound of the genuine” in you. Discover that; discover what makes you come alive and the encounter with the spirit, the encounter with silence, the encounter with God, and that God is a God of justice.

Tippett: And those two things together, that contemplative and justice, that’s an interesting juxtaposition. It’s not where 21st-century minds go.

Moss: No, not at all. [laughs] That’s so true.

Tippett: This is something you said in that documentary. You said, “He was the teacher. He was the mentor. He was the spiritual sage. He was not the one who was on the frontline, but he was the one where people would retreat to, to be filled.” And that emphasis that he had on the connection between interior life, inner life, and outer action, was part of what was revolutionary and part of what was so powerful. It seems to me like you just grew up connecting those things organically, because you were growing up with your father and around all those people.

Moss: I think you’re spot-on, that so much of what we do, especially in America, is so external. It doesn’t nurture the spirit. Everything is transactional. And when you begin to nurture spirit, the spirit as Thurman speaks of, social constructions fall to the wayside, though they inform; but all of the things that we use as markers begin to fall away. And to find the inward sea, as he says, that there’s an island —

Tippett: Did he say, “the inward sea”?

Moss: The inward sea. In the inward sea there is an island that everyone has, in their spirit; that on that island is an altar. And next to that altar is an angel with a flaming sword. And in order to put what is most important on the altar, you first have to find the sea, you’ve got to get to the island, and you gotta get past the angel, so that you can find what is truly genuine in you and what is most important. He said, once you find that, then you come alive. Then you discover what you have been purposed for. And then you begin to work outward. So you work inward to work outward.

Tippett: You have also said that he gave — and you’ve used this word — an Africanity to the interpretation of Jesus. Say some more about what that means.

Moss: Well, he returns Jesus to the African-Asiatic roots prior to the Constantinian framework of Christianity. This mysticism, this engagement, this idea that there are things that we cannot touch nor control, but yet we lean in, nonetheless, was very common. We moved into a very strong doctrinal —

Tippett: Before Western Christendom.

Moss: It was necessary, because it was connected to an empire, and empires demand that you follow particular orders. [laughs] And prior to that, there was this deep encounter idea, what you would call the desert fathers and mothers and all of that. And Thurman returns the faith tradition to the encounter, once again, which Pentecostalism has a strong element of that, but Thurman deepens this Africanity, because his primary theological teacher was his grandmother, who was framing, interpreting scripture and the world through an African lens that she could say, “I appreciate Paul, but there’s some stuff. I don’t like him, because he doesn’t like me.”

Tippett: He tells those stories in Jesus and the Disinherited.

Moss: Yes, it’s so beautiful. And there’s a story that I absolutely love about Thurman, that he tells about his grandmother — that his grandmother owned some land, and there was a white woman who was adjacent to the land and did not like the fact that this Black woman owned land. And so she decided he was gonna get back at Thurman’s grandmother and went to her chicken coop and got all the manure and dumped it on her land and upon her tomatoes and her greens and everything she was growing, to destroy it. But his grandmother, when she realized there was all this manure just had destroyed everything, she would get up in the morning and take the manure and just mix it in with the soil as fertilizer. And so the woman would dump at night, and Thurman’s grandmother would get up in the morning and turn it over and mix it.

And so the woman next door eventually fell ill — and she wasn’t just mean to Black people, she was mean to everybody, so nobody came to see her when she became ill. But Thurman’s grandmother went next door and brought her some flowers. And knocked on the door, heard this frail voice, and she came and the woman was completely shocked that this Black woman, who she had been so cruel to, would come and see her. And she was so deeply moved by the kindness.

And Thurman’s grandmother places the flowers next to the woman, and the woman said, “These are the most beautiful flowers I’ve ever seen. Where’d you get them?” Thurman’s grandmother said, “You helped me make them, because when you were dumping in my yard … I decided to plant some roses.” And Thurman talks about from the manure, what can blossom. There are some who allow the manure to fall on them, and others who just turn over the soil to make something new. Now, that is so African. It comes out of the Black tradition, because we know manure, but we also know fertilizer that can plant new things.

[music: “Mother’s Love” by Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today exploring the present resonance of the mystic and moral theologian of the civil rights movement, Howard Thurman through the life of Pastor Otis Moss III.

[music: “Mother’s Love” by Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou]

Tippett: So you and I are speaking in the momentous year of 2020. And I was watching the sermon that you videotaped, which is how sermons are done right now.

The sermon you delivered on, that you videotaped on May 31 — that would’ve been the Sunday, right? George Floyd was murdered in my city of Minneapolis on May 25 of that week. And your sermon — I want to talk about that; I want to talk about what you preached, and that as a way into how you’re interpreting and applying this theology that we’re talking about, in our time. So you had to do it as a video, and you quoted that great song that we so vividly associate with the civil rights movement of the 1960s, “we shall overcome someday.” And you said, “This is a question, not a statement: When is ‘someday’?” Can you just talk a little bit about what came to you that week? And I want to draw ties between what we’re talking about here, but I don’t want to force that. Just talk to me about that message.

Moss: The fast-moving nature of what was going on that week — we had already witnessed the videotaped murder of Ahmaud Arbery. And then we are hit with the story of Breonna Taylor, which both happened around the same time. But the death of George Floyd — and I didn’t say in the sermon, but I said that he preached a sermon for eight minutes and 46 seconds, and it was just one phrase: “I can’t breathe,” and wanted the world to hear this message. And there were a lot of people that were communicating what I would call very trite, easy theological framing and wanted to co-opt certain words and phrases from the civil rights movement and from the Bible — and this was a moment for lament.

Tippett: Right. That language, that biblical language has never felt more needed — lamentation.

Moss: And America has difficulty with lament because we romanticize history. And we’re so drunk on Confederate wine and don’t even realize it, that when you use lament in some communities and for some ears, they hear that as hate. And I respond that I hate the death of George Floyd and the system that created it. And we have to learn how to lament. Our hearts have to break in the way that God’s heart breaks, in the way that Jesus was lamenting throughout a good portion of his ministry, at what he was witnessing, sometimes turning over tables in anger and in deep pain, or on a tree/cross, saying, “Forgive them. They just don’t know what they are doing.” There’s this lament.

And then, of course, in the Hebraic tradition, the Jewish tradition, the prophetic tradition, the prophets lament. You can’t get through a prophet without a prophet lamenting, crying, and just raging at a nation that just refuses to love and to act with justice. And Thurman clearly communicates that in Jesus and the Disinherited. He talks about the deception and the fear, and moves on to talking finally about the love ethic. But we’ve yet to deal with the internal deception that being a part of America causes us.

What I thought when I was working on that message is, strangely enough, Star Wars.

Tippett: Oh, you and I have more in common than I knew. I like it. Keep going.

Moss: [laughs] It was really a very Star Wars-ian, if I can just make up that word, moment, because within the church and within America in general, there’s the empire and there are the Jedis. And America wants to believe that it’s the Jedi, but in reality, it’s the empire that thinks it’s a Jedi. And so what do you do when you’re trying to exorcise your empire demons, and you want to follow the path of a Jedi? You gotta find a Yoda. And Thurman is our Yoda. [laughs]

Tippett: You gotta train. That’s a word people like Vincent Harding and, I bet, your father, John Lewis, and Ruby Sales — it’s the practice. It’s the training. It’s the honing of your …

Moss: And it’s the failing, too. You fail in the process of training.

Tippett: There’s something so powerful you said in that sermon, which I heard echoes of Thurman. You talked about your understanding of Christianity as “a tradition of hope unafraid to face horror, a tradition of possibility unafraid to stare down pain.” So it’s not about being at all unrealistic, idealistic.

Moss: I have a real issue with the kind of triumphant, easy, quick framings in spiritual traditions and in America in particular, because it feeds into something that is not authentic and not real and not human. And Thurman, who comes out of this Black Southern tradition — if you’re a Black Southerner of that era, you are familiar with horror. You know pain intimately. And you can’t have the kind of faith that says, “It’s just going to be all right.” It’s gonna be all right, but we have to face the pain. And facing the pain doesn’t mean that you become a complete, hopeless, cynic. It means that you operate with a level of realism. And I think Baldwin is best when he says, not everything you face can be changed; but not until you face it can it be changed — that we just have this proclivity to not want to face tragedy.

And I’m sorry to say it, but much of mainline and Western Christianity really is not, [laughs] unfortunately, because it’s been so influenced by the market and — I’ve said before, it’s capitalism in ecclesiastical garments, where it has the robe, but it has no redemption; it has no deep love; it has no deep contemplation. And that’s the challenge. It’s not exclusive.

Tippett: Here is the voice of Howard Thurman in a meditation from February 8, 1952, on the inner life — and how cultural notions have interrupted its natural flow with our outer lives.

Howard Thurman: “The god of religion on the one hand, the god of the sanctuary, the god of the cloister, the god of the dim light, the god of the soft treding step, the god of the holy place, the god of piety, the god of the extremities of life, and then the god of life over here, the god of the marketplace, the god who stays outside. And so persistent is this dichotomy in our thinking and feeling that we tend to split our allegiance right down the center.”

[music: “God Bless the Child” by Gregory Porter]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Otis Moss III.

[music: “God Bless the Child” by Gregory Porter]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being — today with Otis Moss III, an esteemed Chicago pastor who is a bridge between the Black freedom movements of the last century and ours. With him we’re soaking up the teachings of Howard Thurman. Thurman was a mystic as well as a moral anchor for the civil rights movement; a meditator as well as a theologian. His book Jesus and the Disinherited formed the civil rights leaders. And Before this interview, Pastor Moss pointed me to a meditation of Thurman that has influenced his ministry. Thurman taught, “If we believe that life is finished, ready, then we know there isn’t anything that can be done about anything. Or we may be of the mind that life in its essence is not fixed, is not frozen, but life in its essence is fluid, is creative … Purposes therefore, goals, deeds, ideals can fulfill themselves because of the fluid, flowing character of all of life.”

Tippett: Tell me why that message that you sent along is especially important to you.

Moss: The fluidity, the complexity of life and creation and nature, and the music that is within it; that we have to learn how to listen to what we think is this cacophony of just noises, but within it there’s this beat and then there’s this rhythm, and that’s what Thurman is demanding that people reach toward — that you stretch, you don’t reach; you encounter, but you don’t understand.

The vocabulary that we even use for the sacred is so inadequate, because the moment we speak it or think that we have designed, contained it, defined it — that God is so beyond the human vocabulary. But yet, God can be — not known, but maybe the unknown knowable or knowable unknown, depending on how you want to say it, is the way in which we encounter that which is sacred. And so we know something but not enough; it’s just like scooping a teaspoon of water out of an ocean and saying, “Oh, I’ve got it all.” No, you’ve got a few molecules. You can do some study. You can understand a little bit. But the mysteries are too vast. But in that spoon of the little water, you can come to know something on your journey that will assist you. And that, as a person more on the secular end would say, the wildness of God [laughs] fits so beautifully.

And interestingly enough, Thurman’s speaking in that particular piece that I sent also connects to Thurman’s view liturgically. That’s why you have to have the arts in worship. You have to have the dancer, the violinist, and the drummer and the saxophone and the piano. You have to have people who are taking music, which does not have a human vocabulary in the traditional sense, every person who hears it will hear something different. No one hears the note the same way. But yet it’s the same note. It will not touch the person in the same way, but it’s the same note.

Tippett: I wanted to ask you about, in Jesus and the Disinherited — and you mentioned this a minute ago, just briefly, the way he describes the human experience and behavior that we call hate, the way he describes the disease of fear …

Moss: As a disease.

Tippett: … as a disease, and that these things are so alive — they are human reactions that are as old as time, and they are so alive and active and really messing with our life together right now. Um…

Moss: What I love that you stated, you talk about the disease of fear that Thurman speaks about, and about hate and how that is a disease. And we often have not engaged the fullness of experience and how it affects us on that level. And that’s what Thurman challenges the reader and people who listen to him to do. And I’m reminded of an analogy — he always uses these beautiful pictures, usually from nature.

There’s this wonderful meditation that he does, where he talks about what type of spirit are you? He says, are you a reservoir? Do you collect the water and you hold it to be dispensed at a later time? Are you a swamp? Because swamps just hold water, but they have no outlet, only inlet, and that is why so much dies in a swamp, because it’s all for them. But then there are canals and rivers that always are feeding into something else. Decide. Are you a reservoir, a swamp, or a canal?

[music: “Mother’s Love” by Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today: bringing the wisdom of the mystic and theologian of the civil rights movement, Howard Thurman, into the present. We’re doing that through the life and ministry of Otis Moss III. He is the son of civil rights leader Otis Moss Jr. and he’s senior pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. In 2015, he and Trinity helped create a video for Black young people that has rippled around the world. It’s called “Get Home Safely: 10 Rules of Survival.” Here’s an excerpt:

[Excerpt from the short film: Get Home Safely: 10 Rules of Survival]

Tippett: I want to talk about something that feels really hard. You were part of this Get Home Safely video. Again, thinking about “backs against the wall’ and how that phrase resonates again in our time, and it resonates in so many different directions — that was 2015. That was not 2020. That was 2015. Was that a project of the church?

Moss: It was a collective project along with Christian Theological Seminary, Dr. Frank Thomas, who is professor of preaching there at Christian Theological in Indianapolis, along with a film group that was based in Indianapolis. And Dr. Thomas preached for us — he used to preach us every year, in December. And he saw our curriculum, “Get Home Safely.” And he said, “Oh my goodness. Tell me a little bit more about this.” I said, “Well, it’s a curriculum, basically. We’re teaching our children literally how to survive when you leave home. And we are teaching parents what to do if your child” —

Tippett: And you’re talking about Black children and Black parents …

Moss: Black children, yes.

Tippett: … Ten rules of survival if stopped by police.

Moss: That’s right. We want you to come home safely.

Tippett: Just for people who haven’t seen it — and really, these things have gone around the world — there’s a moment in the video — it’s very short; it’s very pragmatic — there’s that moment where the mother is just saying to her son, who we see, “Your goal is to get home safely,” and her voice cracks. And I think, as a mother, you can’t — I guess, in the context of this conversation we’re having, Howard Thurman also wrote incredibly about children. And there’s a part where he says, “The doom of the children is the greatest tragedy of the disinherited. They are robbed of much of the careless rapture and spontaneous joy of merely being alive.”

Here we are, having this conversation in 2020, and it grieves me so deeply that if Howard Thurman came back now, he would see that this is still — this is a reality. My words are very inadequate. But I think you know what I’m …

Moss: I said to my son, Elijah, “You do not have the right to be a frolicking teenager as other children do, because they will see your boyish movements and your laughter and your joking with your friends as a possible threat. You’re going to have to be aware, when you are in certain spaces, around certain individuals, especially if they have a gun. You have to be aware, because I want you home. I want you safe. I want to see you thrive.

Tippett: Do you have this conversation with your father, about how far we’ve come and how far we’ve not come?

Moss: We do. [laughs]

Tippett: What’s that like?

Moss: It’s a wonderful conversation, because my father, who has one of the greatest voices ever — [laughs] he has this deep, baritone voice. You can hear Howard Thurman’s influence in the way that he preaches … And he told me a Thurman story I will never forget. [laughs] He said, “When Thurman was a small boy, he saw an elder, man who must have been in his eighties, who was planting pecan” — or pecan trees, depending on what part of the country you’re from. “And young Thurman raised a question. He said, ‘Sir, you’re not gonna be around. You will not live long enough to taste the fruit from these trees.’ And the old man paused and said, ‘Son, all my life I’ve been eating from trees I did not plant. It’s my job to plant for somebody else.’” And my father said, “Just plant. There will be trees that you will never see grow, that someone else will eat from. And it’s their responsibility to plant for somebody else. And so we don’t have all that we should have, we’ve not reached the goals that we are supposed to reach, but we have started the race, and you’ve got the baton, son. Pass it on.”

Tippett: As you said earlier, Jesus and the Disinherited ends with a chapter on love, having done hate and fear and deception, [laughs] and it ends on love. I thought maybe that would be a good place for us to end. So let me read a little bit of just the first page of this chapter. He’s talking about Jesus. “With sure artistry and great power, he depicted what happens when a man responds directly to human need across the barriers of class, race, and condition. Every man is potentially every other man’s neighbor. Neighborliness is non-spatial. It is qualitative. A man must love his neighbor directly, clearly, permitting no barriers between.” And he goes on to say that this was not an easy position for Jesus to take within his own community.

You speak of the beloved community. It feels like such resonant language now, and I want to know, how do you think about the possibility of love and the work of love in our time, in your generation?

Moss: This moment of racial reckoning, I believe I’ve been given the best glimpse of the beloved community. We have been a part of a variety of protests over these pandemic months [laughs] is the way of framing them now. And I remember going to one particular demonstration early on in the pandemic, immediately after the George Floyd incident and murder. And our church gathered; we put out the call. And we were in the middle of Bronzeville, which is the migration neighborhood in Chicago that Isabel Wilkerson talks about in The Warmth of Other Suns. And here we are, this is the heart of this Black migration, the heart of part of the South Side of Chicago.

And so our church gathered; we were on the other side of the street with some other people and other churches and our BLM organizers and Black Youth 100 and Assata’s Daughters and all of these local activists, primarily South Side and Black. And we looked on the other side of the street, and we saw all these young people with skateboards, who were not from the South Side, and their bikes; then we saw some parents with their children, and young boy holding a sign that said, “White silence is complicity” and another one holding a sign that says, “Black Lives Matter.” And it was the strangest thing, because everybody [laughs] who was Black, on the other side of the street, we all looked at each other, and we said, “What is going on?” [laughs] And then so we started the protest, the demonstration; we all got together. And here we were, the most multiracial gathering, and also in terms of class, and also in terms of orientation. There were people who were gay and lesbian and people who were straight. There were Muslims standing next to Jews, and Jews standing next to Pentecostals, and Pentecostals standing next to Buddhists. Everybody is shouting the same thing: Black Lives Matter.

And that moment, that clarion call, just that moment, and I use this term often, reminded me of the ethic that Black religiosity, Black spirituality has been trying to bring to America for quite some time, and usually embodied in the music, especially the music of jazz, because jazz is about the beloved community and democracy, taking elements that are not supposed to play together, music that comes out of Africanity but then connects with the Indigenous community and those who are French and German in the place called New Orleans, that literally is a gumbo pot of culture. And the instruments in jazz are not supposed to play together. Saxophones are from marching bands. Trap drum sets are not to play with pianos. And basses are supposed to use bows, not your finger. And yet, they all play together, and everyone in the jazz band is given the right to solo, meaning that I can bring my own cultural narrative to the table and in that march I could hear America’s jam session going on. And I got a glimpse of the beloved community. And maybe — maybe, just maybe — if we listen to Thurman, and maybe also listen to Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday, maybe America can be saved.

[music: “Y’Outta Praise Him” by Robert Glasper]

Tippett: Otis Moss III is senior pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. He’s the author of several books and one of the voices in a great documentary “Backs Against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story.” Howard Thurman’s books include Jesus and the Disinherited. His meditations and sermons can be found online at Morehouse College and Boston University. I’m also excited about a new anthology edited by Dr. Gregory C. Ellison II of the Candler School of Theology called Anchored in the Current: Discovering Howard Thurman as Educator, Activist, Guide and Prophet.

Staff credits already recorded: The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, and Ben Katt.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections