Richard Blanco

How to Love a Country

The Cuban American civil engineer turned writer, Richard Blanco, straddles the many ways a sense of place merges with human emotion to make home and belonging — personal and communal. The most recent — and very resonant — question he’s asked by way of poetry is: how to love a country? At Chautauqua, Krista invited him to speak and read from his books. Blanco’s wit, thoughtfulness, and elegance captivated the crowd.

© All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Richard Blanco practiced civil engineering for more than 20 years. He is now an associate professor of creative writing at his alma mater, Florida International University. His books of nonfiction and poetry include Looking for the Gulf Motel and, most recently, How to Love a Country.

Transcript

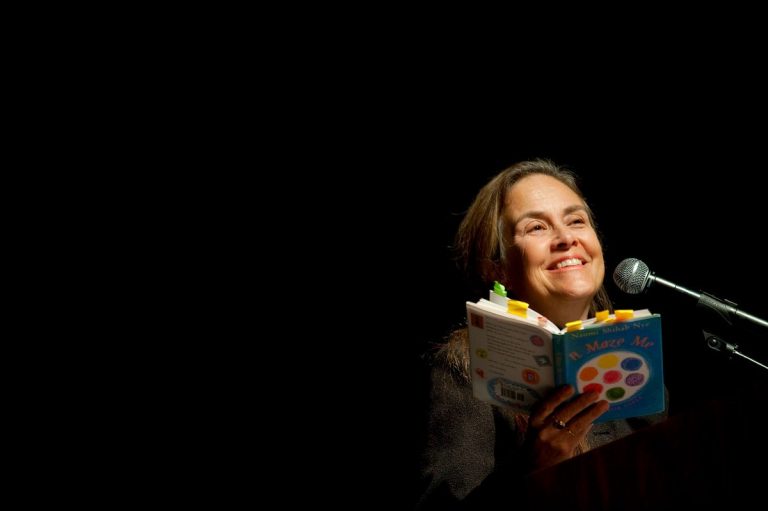

Krista Tippett, host: As a longtime civil engineer by day and poet by night, the Cuban American writer Richard Blanco has straddled the many ways a sense of place merges with human emotion to form the meaning of home and belonging. In 2013, he became the fifth poet to read at a presidential inauguration — also the youngest and the first immigrant. At Chautauqua, I invited him to speak and read from his books. The wit and the deep thoughtfulness and elegance of Richard Blanco’s poetry and his person captivated the crowd. The most recent — and very resonant — question he’s asked by way of poetry is: how to love a country.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Richard Blanco: “We hold these truths to be self-evident…

We’re the cure for hatred caused by despair. We’re the good morning of a bus driver who remembers our name, the tattooed man who gives up his seat on the subway. We’re every door held open with a smile when we look into each other’s eyes the way we behold the moon. We’re the moon. We’re the promise of one people, one breath declaring to one another: I see you. I need you. I am you.”

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. I spoke with Richard Blanco as part of Chautauqua’s 2019 summer season in the historic outdoor amphitheater.

[applause]

Tippett: Richard, you have written, “Every story begins inside a story that’s already begun by others. Long before we take our first breath, there’s a plot underway, with characters and a setting we did not choose, but which were chosen for us.” What I want to do for the next hour here is explore the story of our time, a bit, through the story of your life and the way you’ve captured both of those things in the language and form of poetry. You were 45 days old when you landed in America. That’s the definition of something that was chosen for you.

Blanco: [laughs] Exactly.

Tippett: Just if I asked you that large question, just to get going — “How would you start to tell the story of our time through the story of your life?” — where would you begin?

Blanco: Well, I think, as I like to say, I was made in Cuba, assembled in Spain, and imported to the United States.

[laughter]

It gets even a little crazier: so my mom left seven months pregnant from Cuba; I was born in Madrid —

Tippett: And they went into exile …

Blanco: Exile —

Tippett: … first, to Madrid.

Blanco: First to Madrid — so, where I was born, and then, 45 days later, I emigrated once again. So by the time I was 45 days old, I belonged to three countries and had lived in two world-class cities. And I think writers — I think artists, in general — or, I think, all of us, when something like that really — some kind of origin story like that really imprints us. And of course, I don’t know it’s imprinting at the time, but when I start writing and thinking about that big question — where am I from? Where do I belong in this world? — I think the idea of home was always a big question. It’s still a question that I’m still — a story that I’m still trying to unpack.

And it’s gone through many arcs and periods of love and hate, periods of confusion and delight.

So all of that is still what I’m really working on, even in this latest book; I think, in a way, a question that Whitman was also working on — what is an American, and what does it mean to be an American, and what does it mean to belong to a country, really, in that sense, in this day and age, where that idea is just becoming a little blurry?

Tippett: Shifting.

Blanco: Shifting.

Tippett: You could say that that question of home — what home is and how it feels and how we claim it — is part of the human drama for everyone, but when it is an immigrant story, it just gets — it’s in technicolor from the very beginning. And we’re gonna talk some more about that.

I wonder, was there a religious or spiritual aspect to your childhood, to your formative years?

Blanco: I guess I grew up Roman Catholic, Cuban, Latino Roman Catholic. I went to Catholic parochial school all my life, since kindergarten. And I think there was an interesting base set up there for me, but nothing that I really connected at the moment, at that age. But I think it came back. It came back, somehow. Writing opened that door, that connection to the divine, to some connection to the universe, to the things that be. And I consider writing my spiritual practice.

But again, I think there was a base to that and, also, a little more complicated than just Roman Catholic — the Afro-Cuban idea of Santería and ancestral worship. So that also made it into the writing, in a way, because so much of my motivation to write some of these poems was to document the lives of my ancestors in some ways, their story, their journey, the story I came from, as you said.

Tippett: I feel like, as I’ve delved into your work, the full body of your work, you are reflecting on and articulating aspects of, again, the immigration story of humanity, with a complexity and with all kinds of layers that — although this is a moment in American life, not for the first time, but again — where we speak about immigration, often, in terms of issues and news stories. And I feel like you bring to life a fullness of that experience, which is a human experience. And so I want to draw that out, because I feel like it is very present, very relevant to how we are all inhabiting this moment.

I did read in your — I think your memoir that you said you grew up learning about America and internalizing America through reruns of Brady Bunch, Leave It to Beaver, and My Three Sons. And when I read that, I thought, “Oh, that’s terrible.” And then I realized, I watched all those shows, also. That’s what I grew up on. So we’ve all come a long way. [laughs]

Blanco: I’m bingeing Donna Reed right now. [laughs]

[laughter]

It’s interesting, because — I think, when I first began writing — and again, I say that as a starting point, where I started to ask these deep questions. That’s why I always say, writing makes me think, and thinking makes me write, and there’s a circularity to that as you dive deeper into questions and into yourself, into your soul, into your mind and heart …

Tippett: Yeah, when you write, you also learn what you think, that you didn’t know you were thinking.

Blanco: [laughs] Exactly, and that’s part of what keeps me addicted to it. The story of writing — at first, I shied away from this idea — who wants to hear about such a particular story about a little chubby gay kid from a working-class family in Miami; who wants to hear that story? And I think it’s always been a question that I’ve tried to negotiate. And then thinking about audience and readers, and thinking about whether or not — how am I a catalyst? How am I a bridge to not only understanding my life, but so that others can understand this idea of the immigrant experience or exile experience?

And through the years, to zero in on what you were saying, I finally embraced the idea that in some ways, especially in our contemporary society, we’re all in exile. We all have immigrant experiences of some kind that weren’t happening, exactly, 100 years ago. You move from Miami to Seattle, you’re gonna have an immigrant experience.

[laughter]

You move from Chicago to San Antonio — you get the picture. And I think what Latino writers and immigrant writers or ethnic writers have been doing — and I count myself — not single-handedly, but in a pantheon of a body of work — is set a template for what is, I think, a very contemporary trauma that we’re going through in some ways, of dislocation, location.

Families didn’t disperse the way — just even 50 years ago, families didn’t disperse as much. We can be exiled in social media too, sometimes; we can be isolated. And I always try to think, what does this particular story have to offer universally, and try to write it from that perspective. We’ve all asked that big question, What is home?

Tippett: What is home, yeah.

Blanco: It’s like asking, What is love? And it changes, and it’s complex.

Tippett: And it changes, right. I think something that just is — feels like a large context for a lot of your reflection is, on the one hand — and especially from childhood on — there’s at one and the same time that idealized idea of America that came through The Brady Bunch and comes through many other ways, but also a yearning for the lost home, a deep curiosity. You sometimes describe it as — just in passing, as “my parents’ island paradise,” Cuba.

I wanted to read, there’s this — in City of 100 Fires, this is how you start a poem called “Havanasis.”

“In the beginning before God created Cuba, the Earth was chaos, empty of form, and without music.”

[laughter]

“The spirit of God stirred over the dark tropical waters, and God said, ‘Let there be music.’ And a soft conga began a one-two beat in background of the chaos.”

Blanco: There you go. [laughs]

[applause]

You read that wonderfully, by the way.

Tippett: Oh, thank you. Well, thank you.

Blanco: It’s always a little weird when people read; that was perfect timing. I loved it.

Tippett: Oh, well, wonderful. That makes me happy.

But then I wonder, also, if you would read, as a counterpart to that, in this book, page three, “América.” Do you have this one? I have it for you. I told you, you’re not going to have to do any work if you don’t want to. No, it’s on page four — I did say to Richard that because this is radio, short poems are better. And he doesn’t really do short poems.

Blanco: No. Cubans don’t write short poems. [laughs]

Tippett: But your poems are very narrative.

Blanco: Exactly.

Tippett: So we’re gonna hear some great poetry today. So maybe start — because this is just so wonderful — start here, at number four, and then, you can …

Blanco: So the context here, just so everyone knows, Thanksgiving is, of course, for an immigrant — almost any immigrant group — it’s just one of those things we don’t get. [laughs] And we try really hard, and Latinos or, at least in my Cuban community, we call it “San Giving,” like San Pedro or San Ignacio. It’s a whole other kind of feast day.

[laughter]

And the same is true — there’s still sort of a yearning between this mythic homeland that is Cuba, that I don’t really know and this mythic homeland that is the Brady Bunch house, which I want to buy someday. [laughs] And so you’ll see this — this is all in the context of Thanksgiving, and Ricky trying to negotiate those two yearnings.

“A week before Thanksgiving

I explained to my abuelita

about the Indians and the Mayflower,

how Lincoln set the slaves free;

I explained to my parents about

the purple mountain’s majesty,

‘one if by land, two if by sea’

the cherry tree, the tea party,

the amber waves of grain,

the ‘masses yearning to be free’

liberty and justice for all, until

finally they agreed:

this Thanksgiving we would have turkey …

[laughter]

as well as pork.

[laughter]

Abuelita prepared the poor fowl

as if committing an act of treason,

faking her enthusiasm for my sake.

Mamà set a frozen pumpkin pie in the oven

and prepared candied yams following instructions

I had to translate from the marshmallow bag.

The table was arrayed with gladiolus,

the plattered turkey loomed at the center

on plastic silver from Woolworths.

Everyone sat in green velvet chairs

we had upholstered with clear vinyl,

except Tío Carlos and Toti, seated

in the folding chairs from the Salvation Army.

I uttered a bilingual blessing

and the turkey was passed around

like a game of Russian Roulette.

‘DRY’, Tío Berto complained, and proceeded

to drown the lean slices with pork fat drippings

and cranberry jelly–‘esa mierda roja,’ he called it.

Faces fell when Mamá presented her ochre pie—

pumpkin—calabasa—was a home remedy for ulcers, not a dessert.

[laughter]

Tía María made three rounds of Cuban coffee

then abuelo and Pepe cleared the living room furniture,

put on a Celia Cruz LP and the entire family

began to merengue over the linoleum of our apartment,

sweating rum and coffee

sweating rum and coffee until they remembered—

it was 1970 and 46 degrees—

in América.

After repositioning the furniture,

an appropriate darkness filled the room.

Tío Berto was the last to leave.”

Tippett: Thank you. [applause]

Tippett: So before we move on and keep going with more poetry, I do want to note that although most Americans first came to know about you as the poet of a presidential inauguration, you were a civil engineer before you began to write, and were you still a full-time civil engineer when you delivered the inaugural poem?

Blanco: Yes. Yes, I’ve been a practicing civil engineer all my life.

Tippett: So this has been — this has essentially been your career, which I find fascinating. And I think, at first, it might sound like a surprising juxtaposition, but the more I thought about it, it makes a lot of sense, because it’s about design and structure and patterns.

Blanco: Yes. You got that. You hit that right on the nose. As careers, they’re obviously different career paths; you’re not in a cubicle all day. But I learned a lot about writing poetry from my math classes, in terms of structure, logic, patterns, as they say, musicians say, music is very mathematical. So that lent itself to writing. And vice versa, being a civil engineer, I had to engage with a lot of public, a lot of communities and towns. And being a writer, being a poet, which is, in some ways, partly a study of human nature, it really built my skills in terms of trying to understand people, their nuances in what they’re saying, what they’re not saying, and tease out of them their emotional relationship to place and home and projects that were civil projects for everyone to enjoy, which, ironically, is what my poetry is about — trying to find a psychological home; but also, in my engineering, I was, in a way, creating brick-and-mortar home, a sense of home with brick and mortar.

And it’s really interesting, because I think it speaks, also — you hit it right on the nose. It’s not that different. But I think it speaks to our general attitude — well, and still, how we silo education and “oh, you’re an engineer” — it’s getting worse and worse, I think, these days — “you’re an engineer; you don’t need to learn how to write.” My job was 50 percent writing. And I didn’t start writing until I stepped into my consulting office and had to write, and that actually led to my love of language, in a way, too, was, I started exploring language, and then I got deeper and deeper into it and became the go-to person and the senior partner, because of my writing. An engineering proposal that gets in a $40 million job is nothing but a narrative, an argument, a persuasion of how our firm is the best firm, our vision for the project.

But it is funny, sometimes, because interviewers get it wrong. [laughs] The romantic story is that “I was forced to study engineering because of my working-class family, and then I discovered poetry, and the clouds parted, and the cherubs came down, and…”

[laughter]

And my response is, “I really, really wanted to go full-time into poetry, because there was so much money …

[laughter]

… but I really felt an ethical obligation to stay in engineering.”

And so there’s kind of a practical matter, but I loved the balance, too. And it created — for me, at least, I’m a left-brain person — and I loved the balance. And I guess I just want to say, for writers out there, too, and especially young writers that are thinking about becoming writers as professional writers, that just because you have another career doesn’t make you a sellout. In fact, as long as you keep a focus and your vision and you find something that works for you — and every journey and how you come to do something is unique, and I’m proud of having those seemingly contradictory careers and vocations.

Tippett: I love the way you describe what is actually true, that the emotional — practical and emotional needs that you need in a good design — that poetry is another way of delving into those things. And we do try to separate — we pretend like these are separate disciplines, when it’s about being whole.

Blanco: It’s all one thing, I think.

Tippett: All one thing.

Blanco: If we think upon any innovation of any sort of breakthrough, it’s really about synthesis of seemingly disparate or nonrelated knowledge or pieces of knowledge. My sense of place — I have — it’s not quite a theory, but the way I’ve been thinking about it lately as an engineer — that everything has a physical landscape, an emotional landscape, and a natural landscape. And I think the way those three things combine form our sense of place and belonging and connection.

Tippett: So all of that is another way to speak to the true complexity of these themes that for you are so important, for all of us are so important, of place and belonging and the fullness of that, and our wrestling with that. I have to say, one thing that really stuck out with me as I have gotten to know you is that also, as part of this story of what it means to be an American, is that Richard Blanco is not really — it’s a part of your name.

Blanco: Yes. [laughs]

Tippett: I interviewed Martin Sheen, who is Ramón Estevez, and our executive producer, whom I’ve always known to have two names, it turned out, after I’d known her for many years, that she’s reclaimed — she’s Colombian American — all of her names. So tell us your full name that you were born with.

Blanco: My full name is, technically, Ricardo de Jesús Blanco Sánchez Valdez Molina, because I was born in Spain, and they tack them all on. [laughs]

[laughter]

But it’s funny, because naming is one of those things that — also sort of origin stories. Naming is such an interesting thing, how we rename ourselves or not. I love how rock stars rename, like Freddie Mercury. [laughs] There’s the name you’re given and then there’s the name you take on or you feel describes you or captures you in a different way.

The problem — not the problem, but the backstory beyond that, and I don’t think I’ve ever quite written about it, but — so I was named after Richard Nixon.

[laughter]

It had nothing to do politically, because my parents are in Spain. I am born; they just wanted to come to the United States, so I was named Ricardo, after Richard Nixon. Jesus, because — [laughs] my middle name is Jesus, because my mom, on that transatlantic flight, said, “If we make it alive, her middle name will be Jesus.”

[laughter]

And then — as I look back, the way I would’ve liked to rename myself, which would’ve been — I put Richard because I like the contrast of the Anglo and then the white, Blanco.

Tippett: Is it true — did you ever think about calling yourself Richard White?

Blanco: Well, my standing joke now is “Dick Jesus White.” [laughs]

[laughter]

And I think it’s comical, because in Protestants’ world, nobody names their kids Jesus. But it’s so common in Roman Catholic Latino society to — but it just doesn’t translate. So: Richard Nixon and Jesus, and they wonder why I became a poet and an engineer. Hello? [laughs]

[laughter]

Tippett: I feel like we could keep going on that for the next 45 minutes. It’d be really fun, but we’re gonna change — we’re gonna turn a corner.

At On Being, we have put poets on the air the last two election weekends, and I think we’ll probably keep going with that practice. I lived in divided Berlin in the 1980s. I’ve experienced in my lifetime how poetry rises up, in culture after culture — especially in moments of crisis, especially when official discourse and words are failing us or inadequate for what we have to grapple with and when we really have to reach for new language and new ways with language, among other things, to give voice to what we need and want to give voice to. In a way, it’s a corollary to what you describe about the synergy between engineering and poetry — that we have to meet the practical needs with our emotional needs, the psychological with the political.

You’ve quoted Elizabeth Bishop, somewhere, saying, it’s not about what’s said but about what’s not said, [Editor’s note: Mr. Blanco references Elizabeth Bishop in this interview. While there’s no record of Bishop speaking to this idea directly, Kathleen Spivack describes Bishop’s poetry in this way in her book.] and I also feel like poetry leaves room for silence. And poetry makes room for questions that are unanswerable and for them to sit there.

Blanco: Yeah, I’m starting to see it more connected to the idea of how music happens in us, happens in the writing of the poem and, also, how it imprints in us, in the same ways that sometimes we can hear a song, and we’re not exactly sure — the words are saying something, but there’s an imprint that’s something we can’t always place a finger on. “my father moved through dooms of love / through sames of am through haves of give” — I have no idea what that means …

[laughter]

… but there’s a pleasure — and I actually don’t want to break it down that much, but there’s a beautiful pleasure. I know what it means, on another level. And those empty spaces, like in music — I think poetry affects us that way, and it’s not usually taught that way. It’s taught like, “Let’s pin down the frog in anatomy class, and let’s pull it apart” — and that’s important, too, to a certain degree, but it’s not usually taught to just let it be in us and let it breathe in us. I don’t know where the Hotel California is, [laughs] or how to get there, but I love that song. And how we can read poems over and over — everybody has a favorite poem. We can read that poem over and over again. We rarely go back and reread novels or memoir. And it’s like music. You can always hear your favorite song over and over again.

Tippett: Well, and to your point, also — I also think poetry got — it became this scholarly pursuit, for some people and not for others; and yet, we are all hearing poetry and enjoying it and claiming it through songs all the time, and the bible is — and actually, all, every religious and spiritual tradition I can think of has always known to convey — that there’s some truths can only be conveyed through poetry.

Blanco: Psalms …

Tippett: The Book of Job is an epic poem.

Blanco: … the prayers, that’s one of the things I say before I get up to read, is always the prayer of St. Francis. There’s this beautiful meaning, but also language, in there, and it grounds me in a way that’s not just spirituality, though that’s a big part of it, but it’s also language.

Tippett: Well, so I think what I’d really like to do is get into your newest volume, How to Love a Country. Right at the beginning of this book you have this line: “Tell me with whom you walk, and I’ll tell you who you are.” You have that in Spanish and English. You don’t attribute that to anybody. What is that?

Blanco: It’s never been attributed to any — even an anecdote of a story, or any one person. But it’s a really popular idiom or saying in Spanish, “Dimé con quién andas, y te dire quién eres.”

I took a lot of chances in this book, because I broke out of just talking about my sense of home or my Americanness and started, like I say — I think I moved from the poetry of “I” to the poetry of “we.” And so I started thinking, who am I walking with? Who has come before me, and who has walked before me? And this idea of ancestry, again, of stories — you’re born into someone else’s story, and you walk, and then you give that story to someone else. But I was thinking, who are we? Who are we, as a country? And how are we walking together? And there’s a beautiful, also — maybe it was inspired, also. One of the department heads at my alma mater, she has a saying from the Caribbean that says, “Walk good,” [laughs] which is what your mom tells you: “Walk good.” And I was thinking about, what is the company, past and present? Who are we walking with? And how, together, what are we doing?

[music: “Drume Negrita” by Ry Cooder and Manuel Galbán]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Richard Blanco. You can always listen again wherever podcasts are found. And you can dwell with all the poetry from this hour — and much much more — at the Experience Poetry home at onbeing.org

[music: “Drume Negrita” by Ry Cooder and Manuel Galbán]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with Richard Blanco, the Cuban American civil engineer turned poet. We’re exploring themes of home and belonging — physical and emotional, personal and communal — as Richard Blanco takes them up in his book, How to Love a Country. We spoke in the outdoor amphitheater of the Chautauqua Institution.

Tippett: I said to you before we came out here, if you feel called to read anything from any of those books, you may do that. But I’m going to propose — I pulled some out that — it’s interesting. You use the word “immigrant.” That’s the way you describe your family story, I think, most often, or “exile,” a bit. I had a conversation last year about Hannah Arendt, [Editor’s note: Krista is referring to her interview with Lyndsey Stonebridge, which took place in 2017.] who wrote a lot about exile. And the conversation I was having with this scholar of Hannah Arendt, who works with refugees now, is what happens to our imagination about these humans when we use the word “immigrant” or “refugee” or, what I’m so aware of now, is what the word “migrant” has done. I think that language makes an abstraction of people and creates an ability for us to separate. Anyway, this is just on my mind. And then you wrote this poem called “Complaint of El Río Grande,” which is, again, looking at this entire drama from a whole different angle, which is this piece of the natural world that is crossed and that, in that moment, makes of people … whatever that thing is.

Blanco: Something transforms.

Tippett: Want to read that one?

Blanco: Sure, I’d love to.

Tippett: Page nine.

Blanco: Given me a lot to think about there, but … [laughs] but we’ll read it first, like you said. So I’ve been hearing about the Mexican-U.S. border since I was a kid. And I think we all, in some ways, are — just sort of had it with this issue, in the context of, you mean to tell me that we can’t, not just as countries, as the Western hemisphere, come to some kind of fair, amicable, humane — to this problem that is not — we’re making it a problem.

And it gets abstracted, and it gets politicized, overly politicized, and I thought, how can I do this, is, let the river speak. And let the river — so this is a persona poem in the voice of the river — to let all humanity have it; [laughs] have the river pointing a finger at us, so to speak.

“I was meant for all things to meet:

to make the clouds pause in the mirror

of my waters, to be home to fallen rain

that finds its way to me, to turn eons

of loveless rock into lovesick pebbles

and carry them as humble gifts back

to the sea which brings life back to me.

I felt the sun flare, praised each star

flocked about the moon long before

you did. I’ve breathed air you’ll never

breathe, listened to songbirds before

you could speak their names, before

you dug your oars in me, before you

created the gods that created you.

Then countries—your invention—maps

jigsawing the world into colored shapes

caged in bold lines to say: you’re here,

not there, you’re this, not that, to say:

yellow isn’t red, red isn’t black, black is

not white, to say: mine, not ours, to say

war, and believe life’s worth is relative.

You named me big river, drew me—blue,

thick to divide, to say: spic and Yankee,

to say: wetback and gringo. You split me

in two—half of me us, the rest them. But

I wasn’t meant to drown children, hear

mothers’ cries, never meant to be your

geography: a line, a border, a murderer.

I was meant for all things to meet:

the mirrored clouds and sun’s tingle,

birdsongs and the quiet moon, the wind

and its dust, the rush of mountain rain—

and us. Blood that runs in you is water

flowing in me, both life, the truth we

know we know: be one in one another.”

Thank you.

[applause]

Thank you. Gracias.

That poem still does things to me. I’m still learning, myself — it’s interesting, the creative process and how that connects. I always say, my poems are smarter than me. I’m not that smart — I go through this whole physiological experience when I read that poem again, and thinking about that river, being that river.

Tippett: Would you read “America the Beautiful Again”?

Blanco: Oh, sure.

Tippett: Page 66.

Blanco: Six-six. Part of this poem was, the title of this book, How to Love a Country, is a statement; it’s also a question. It’s also a self-help book [laughs] for today, a how-to book, maybe. One thing, again, like you were saying about language, why write a book that — I didn’t want it to be a one-beat kind of book, and I also wanted to explore different things, and I didn’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater and be poems just of protest. And I just went back to this poem of patriotism, but the kind of innocent patriotism that you feel as a kid, that pure kind of love for ideals and, at least for me, what this country stands for — I think, still stands for; and so this is going back to that space. And I’ll sing a little bit, which is — you can leave, if you want.

[laughter]

You have your chance now.

So it’s “America the Beautiful,” which is obviously a reference to the song.

“How I sang O, beautiful like a psalm at church

with my mother, her Cuban accent scaling-up

every vowel: O, bee-yoo-tee-ful, yet in perfect

pitch, delicate and tuned to the radiant beams

of stained glass light. How she taught me to fix

my eyes on the crucifix as we sang our thanks

to our savior for this country that saved us—

our voices hymns as passionate as the organ

piping towards the very heavens. How I sang

for spacious skies closer to those skies while

perched on my father’s sun-beat shoulders,

towering above our first Fourth of July parade.

How the timbre through our bodies mingled,

breathing, singing as one with the brass notes

of the marching band playing the only song

he ever learned in English. How I dared sing it

at assembly with my teenage voice cracking

for amber waves of grain that I’d never seen,

nor the purple mountain majesties—but could

imagine them in each verse rising from my gut,

every exclamation of praise I belted out until

my throat hurt: America! and again America!

How I began to read Nietzsche and doubt god,

yet still wished for god to shed His grace on

thee, and crown thy good with brotherhood.

How I still want to sing despite all the truth

of our wars and our gunshots ringing louder

than our school bells, our politicians smiling

lies at the mic, the deadlock of our divided

voices shouting over each other instead of

singing together. How I want to sing again—

beautiful or not, just to be harmony—from

sea to shining sea—with the only country

I know enough to know how to sing for.”

Thank you.

[applause]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with civil engineer and poet Richard Blanco.

[applause]

Blanco: Thank you.

Tippett: I sometimes ask, at the end of a conversation, this question: What’s making you despair right now, and where are you finding hope? And I feel like we’re so articulate about our despair. And I feel like what is making your heart ache, we’ve heard. I would like to ask you where you’re finding joy, where you’re finding hope right now.

Blanco: Sure. I think it’s interesting, because I was just at that point — I do a small radio segment; it’s called “The Village Voice.” We share poems, sometimes mine. And this — it’ll air next week, but I called it National Oblivion Day, [laughs] and the poems were like, “I can’t take it anymore.” And it was also like, one of the great things that poetry does is allows us to just go to that space so deeply — that somehow we let go of it in some ways. So I’m looking for poetry that does that, that lets me acknowledge and be OK with where we are right now. And that helps a little bit. But I’m trying to think — I guess what keeps me hopeful — and this is something that I — it’s sort of in between all this despair and fear and apprehension — I think one of the most beautiful things that I see, and it happened first with the ban on Muslims and whatnot, that people, at least in my lifetime, for the first time, were standing up for something that didn’t affect them directly, directly. That is a democracy.

[applause]

And so I just love — I just love that we’re stepping up, and we’re realizing, no. OK, this is — I don’t have to go to that protest; it’s not about me. But that poem from the — you know, “First they came for the so-and-so”? Remember that poem? And I think we’re finally — we’re not doing that. We’re not waiting for them to come for us. We are stepping up and realizing that the quality of life, the virtue of this country, depends on every human being’s story, to a certain degree; that our happiness depends on other people’s happiness, and we’re moving from a space of dependence to realizing our interdependence.

And I just think that’s beautiful. Even with the questions — this book was scary in some ways, because I’m broaching subjects that, somehow, I also felt I didn’t have permission to write about, like about Mexican immigration. Well, no, there’s a common ground there. Race, gender, all these kinds of issues. And I think that’s what I’m trying to do, is I’m also trying to embrace everyone else’s experiences and, perhaps, coming up with language together, or saying, “Me too.” So I just love that that’s happening. And it’s hard to see, between the 24-hour newsreel and the clips, so …

Tippett: It becomes a discipline, almost like a spiritual discipline, to take that seriously, too. It’s a way of us, some of us, enough of us, collectively, living this phrase that you have at the beginning of the book, How to Love a Country: “Tell me with whom you walk, and I’ll tell you who you are.” So it’s us, expanding that sense of who we are.

Blanco: And realizing that we’re walking together — or we always have, but actually acknowledging that now.

Tippett: So the book begins with “The Declaration of Interdependence.” Is there a story behind this poem?

Blanco: Again, finding language, finding another angle, finding another dialogue, and how easily stereotyped and typecast people can become in the news; and, also, how we do it to ourselves — “Oh, you drive a red pickup truck; therefore, you must be this person. You shop at Whole Foods; therefore, you must be this kind of person. You drive a Subaru; therefore, you must be this kind of person,” and realizing that that’s really something that’s been slowly chipping away at our brains, this sort of immediate — I won’t say “judgment,” but a typecasting that sometimes, we’re not even aware. So I just wanted to break down some of those stereotypes and create empathy across those stereotypes.

But it also, ultimately, comes from a saying, a greeting from the Zulu people, that was the real inspiration here. The greeting — they don’t say “Good morning” like we do, like we did, this morning. “Good morning; I need coffee.” [laughs] They look at one another, right in the eyes, and say, “I see you.” And there’s an incredible power in seeing and being acknowledged. And if I’m not mistaken, the reply is, “I’m here to be seen. And I see you.” And so we just — we’re not seeing each other as clearly, and I think this poem was trying to let us see each other clearly.

And it’s got — “Declaration of” — I think I mentioned, the next evolvement in our consciousness is from dependence to independence is, really, interdependence. That’s really where, as a country, as a people, as a family, as a world … [laughs]

Tippett: As a species …

Blanco: As a species. If we don’t do that in the face of — well, we [won’t] touch climate, but — [laughs]

“Declaration of Interdependence” — and these are excerpts from the Declaration of Independence.

“Such has been the patient sufferance…

We’re a mother’s bread, instant potatoes, milk at a checkout line. We’re her three children pleading for bubble gum and their father. We’re the three minutes she steals to page through a tabloid, needing to believe even stars’ lives are as joyful and as bruised. Our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury…

We’re her second job serving an executive absorbed in his Wall Street Journal at a sidewalk café shadowed by skyscrapers. We’re the shadows of the fortune he won and the family he lost. We’re his loss and the lost. We’re a father in a coal town who can’t mine a life anymore because too much and too little has happened, for too long.

A history of repeated injuries and usurpations…

We’re the grit of his main street’s blacked-out windows and graffitied truths. We’re a street in another town lined with royal palms, at home with a Peace Corps couple who collect African art. We’re their dinner-party talk of wines, wielded picket signs, and burned draft cards. We’re what they know: it’s time to do more than read the New York Times, buy fair-trade coffee and organic corn.

In every stage of these oppressions we have petitioned for redress…

We’re the farmer who grew the corn, who plows into his couch as worn as his back by the end of the day. We’re his TV set blaring news having everything and nothing to do with the field dust in his eyes or his son nested in the ache of his arms. We’re his son. We’re a black teenager who drove too fast or too slow, talked too much or too little, moved too quickly, but not quick enough. We’re the blast of the bullet leaving the gun. We’re the guilt and the grief of the cop who wished he hadn’t shot.

We mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor…

We mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor…

We’re the dead, we’re the living amid the flicker of vigil candlelight. We’re in a dim cell with an inmate reading Dostoevsky. We’re his crime, his sentence, his amends, we’re the mending of ourselves and others. We’re a Buddhist serving soup at a shelter alongside a stockbroker. We’re each other’s shelter and hope: a widow’s fifty cents in a collection plate and a golfer’s ten-thousand-dollar pledge for the cure.

We hold these truths to be self-evident …

We’re the cure for hatred caused by despair. We’re the good morning of a bus driver who remembers our name, the tattooed man who gives up his seat on the subway. We’re every door held open with a smile when we look into each other’s eyes the way we behold the moon. We’re the moon. We’re the promise of one people, one breath declaring to one another: I see you. I need you. I am you.”

[applause]

Tippett: Thank you, Richard Blanco.

[applause]

[music: “The Zeppelin” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Richard Blanco practiced civil engineering for more than 20 years. He is now an associate professor of creative writing at his alma mater, Florida International University. His books of nonfiction and poetry include Looking for the Gulf Motel and, most recently, How to Love a Country.

Speaking of poetry, all the poems Richard Blanco read this hour are part of a new offering of solace and sanity — the Experience Poetry home at onbeing.org. There are short-form and deep dives for any time of day, any kind of day. Our world is noisy, challenging, and tumultuous. But you can get tethered, and be recharged, and find your way to a deeper view, a longer view. Poetry helps. Again, Experience Poetry at onbeing.org.

The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, and Gautam Srikishan.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections