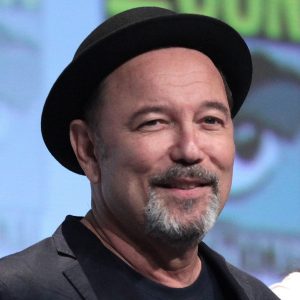

Rubén Blades

The Ox-Bow Incident

Movies can fundamentally shape the course of our work. That’s how the 1940s noir-Western The Ox-Bow Incident transformed salsa musician-activist-lawyer Rubén Blades. It taught him that it wasn’t enough to speak about justice — he had to defend its ideals.

© All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Rubén Blades is a Panamanian singer, songwriter, actor, musician, activist, lawyer, and politician. He has too many incredible albums to list, but Lily's favorite is Siembra, which he made with Willie Colón — it has the songs "Pedro Navaja" and "Plastico," which you should definitely check out.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, fellow movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with Rubén Blades about the movie that changed his life, The Ox-Bow Incident. You may not have heard of it. I certainly hadn’t — but don’t worry. We’re going to give you all the details you’ll need to follow along.

[music: “Buscando America” by Rubén Blades]

The song we’re listening to is called “Buscando America.” It’s by Rubén Blades, one of my heroes and someone that has influenced my life in profound ways. He’s a musician. He’s perhaps one of the biggest salsa musicians of our time, and he’s also an activist and a lawyer — something that a lot of people don’t know about him. And I wanted to talk to Rubén because I know that he loves movies. He’s actually been in a lot of movies, credited here in the U.S. as Ruben Blades instead of Rubén Blades. And I have to say that the movie that he picked was one that I’d never heard of before, The Ox-Bow Incident. It’s a movie from the 1940s — 1943 to be exact — by William Wellman, and it stars Henry Fonda and Harry Morgan. It’s a movie about vigilante justice, about what happens when crowds gather together in anger and throw away the law as a result.

The movie is set in a Western town, and a crime happens: One of their own is murdered — or so they think — and a group of men, a posse, goes after three other men who have been accused of the murder.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Ms. Percy: What makes the movie so tense is that you don’t actually know if they’ve done it or not, but this posse is so hell-bent on getting justice that they don’t really care.

Once I watched The Ox-Bow Incident it made complete sense that this movie changed Rubén’s life. Rubén has been a leader in Latin American politics, in social justice movements. His music is played at every party, every wedding, every protest march, because he is the voice of the people. And watching The Ox Bow Incident as a little boy inspired Rubén to become a lawyer. He knew that he wanted to fight for the rights of others, those who didn’t have a voice. He wanted to be that voice for them.

Ms. Percy: So Rubén, just to give you a little background, this whole series — the idea behind it is talking about a movie that changed your life. And I love that you talked about The Ox-Bow Incident, a movie I had never seen, and it was such a thrill for me to watch it. So before we delve into that movie, I just want to know what role movies have played in your life. What significance have movies, in general, had for you?

Rubén Blades: The significance of movies in my life was very, very important, in the sense that they were examples that were presented to us at a time when movies all seemed to need to have una moraleja: a lesson.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, a morality.

Mr. Blades: Morality tale; a lesson. And my mother, my grandmother, God bless them both — we used to live very close to a movie theater in Panama called the Edison Theater. And we lived in a very small — we had like two rooms or something, so it was always crowded, and during the summer, it was very hot. So this movie theater had probably the coldest air conditioning unit in the Western Hemisphere known to mankind at the time, and we could pay a dime and go there and see three movies — la cómica, cartoons, and documentaries. And we ended up going, a lot, to the movies. And I remember my grandmother always telling me — for instance, if we saw a cowboy movie, we saw somebody get hit and go down, and the other guy would wait for the guy to get up. He wouldn’t hit him on the floor.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, there’s a moral code.

Mr. Blades: And I asked my grandmother, why? And she said, because you’re not supposed to hit people when they’re down. Yeah, there were a lot of lessons that we learned. Some of them were good, and some were bad. For instance, the fact that at the time, there were no blacks in the films.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, no kidding.

Mr. Blades: They really weren’t around unless they played certain roles, stereotyped roles: the porter or the shoeshine guy or the waiter, server, or something; the fact that there weren’t many women in roles of power. Also, the fact that we applauded when the cavalry came and killed the Indians.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, they were the bad guys.

Mr. Blades: Yeah, so they were things that formed you and also helped to deform you. But I remember the good ones, the good examples, and The Ox-Bow Incident was one of them.

Ms. Percy: I don’t know if you’re familiar with Fred Rogers from Mister Rogers?

Mr. Blades: Sure.

Ms. Percy: Well, when he accepted his Lifetime Achievement Daytime Emmy, he did this amazing thing with the audience where he asked everyone in the audience to take ten seconds to think about everyone that had brought them to that point. And I’m not gonna ask you to do that, but I am gonna ask you to take ten seconds and just close your eyes and think about The Ox-Bow Incident and the first time that you saw it — how old you were, where you were, all the memories that come to you. And then I’ll chime in after ten seconds.

So where were you transported to then?

Mr. Blades: I was in Panama. I saw that film with my parents — not my parents, with my grandmother. I don’t think I saw it at the Edison. I think I saw it at the Variedades Theater.

Ms. Percy: Do you remember how old you were, or approximately how old, or what year it would have been when you saw this?

Mr. Blades: If I saw it with my grandmother, I must have been anywhere between three and five, first. And I saw it again — probably I was 14. I remember I was in school, and it was an important thing, because those were elements that ended up with other influences, personal influences, like my grandmother and my mother and my father, and of readings, which ended up pushing me towards law.

Ms. Percy: It’s so interesting to me, because, as I mentioned to you, I had never seen this movie before you recommended it. And watching it, I looked up to see what people wrote about it at the time, when it came out in 1943. And it was interesting that the New York Times review of it — have you read the New York Times review of the movie?

Mr. Blades: Yes.

Ms. Percy: Do you remember this line? It says, “It’s hard to imagine a picture with less promise commercially.” And it said, “It exhibits most of the baser shortcomings of men — cruelty, bloodlust, sordid pride. It shows a tragic violation of justice with little backlash to sweeten the bitter draught.” And then it said, “The Ox-Bow Incident is not a picture which will brighten or cheer your day. But it is one which, for sheer stark drama, is currently hard to beat.”

Mr. Blades: And also, there was another gentleman who was incensed by the movie, I remember. It was a review that just panned it, said it was a horrible movie. And “How did they waste their time doing such a movie with such a horrible premise?” — because those are the people who feel that art and film or painting or music or anything just has to be directed towards escape.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, to entertain.

Mr. Blades: And entertainment, basically, and not used for any other function. And it’s interesting that now The Ox-Bow Incident is one of the 100 films — it’s certainly the Western film noir of all time, I think.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Ms. Percy: The Ox-Bow Incident speaks to so many important issues: the idea of right and wrong; what happens when a vigilante mob mentality is allowed to enact justice.

Mr. Blades: And how quickly we jump to conclusions.

Ms. Percy: And I’m curious — you talked about how this influenced you as a lawyer. What lessons did you learn and carry from that movie that really led you?

Mr. Blades: Well, the need that justice must be — that the ideal must be defended in order for it to exist. It’s not enough to speak about justice. You really have to enforce it. You have to be a part of its defense, and that people that are not given justice are abused, just the same way that I would be abused if I don’t have access to it. So I felt I wanted to be on the right side of history. I saw that, and I suffered. It pained me to experience what those men had experienced. It’s just as if they hung me, or a part of me, as well, that day. And it was irreversible.

That’s another thing that affected me. I thought, gosh, when this happens, people are totally without any type of protection. They just succumb. That’s it.

And I thought, well, the system has to make people aware of our own capability of being wrong and not to take the law by our own hands. And, again, this is a situation where people who are not actively supporting the misdeed actually become accomplices of it for not saying anything. That was another thing that I remember that I got out the film: You have to talk about it. You have to be a part of it. You have to denounce it. You have to accept that you’re wrong, or accept wrong and face it.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, and speak up in the moment.

Mr. Blades: And they didn’t. They did not, because they felt they didn’t have all the information, that they could’ve been wrong. And although they did not approve of it, they ended up joining the wrong. And I remember feeling about that and thinking, well, how many times do we do that every day?

Ms. Percy: We hold back from speaking up for someone, something that we see is wrong. Yeah.

Mr. Blades: Yeah, because we’re afraid. We’re afraid of being wrong, and we’re afraid of consequences, and we say, well, actually, I don’t know. I don’t know. It could be.

But the point there was not about whether or not they could have murdered Kincaid. The thing there was, you’re not supposed to hang people without a fair trial.

Ms. Percy: Exactly.

Mr. Blades: That’s the point. And they were not strong enough in opposing that.

Ms. Percy: And that’s why the scene where the sheriff comes upon the mob, and he says, “Larry Kincaid’s not dead” — that scene just gave me chills.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Mr. Blades: And this is the other thing with the audience, is that we don’t know what happened until he shows up.

Ms. Percy: Yes. Until he shows up and says that, we don’t know.

Mr. Blades: Because it could have been; it could’ve happened. This movie was so smart in so many ways, because whenever you see a film in those days, and even now, when you see a film and you see the headliners, the names — Henry Fonda, Harry Morgan — you know they’re not gonna die.

Ms. Percy: Anthony Quinn, which I always forget.

Mr. Blades: Well, Anthony Quinn, it’s an interesting — you know how his role was described as?

Ms. Percy: No, how?

Mr. Blades: “Mexican.” He didn’t even have a name. The role was described as “Mexican.” He was great.

Ms. Percy: Oh, so great.

Mr. Blades: And again, he did a lot with very little. But anyway, the fact that they put these main roles in an ambivalent position — they weren’t heroes. Henry Fonda was not a hero in this movie, and neither was Harry Morgan, so the hero was the guy who died, who was abused.

Ms. Percy: Which is so counter to Westerns of that time, where there was a very clear hero.

Mr. Blades: And movies in general. Because again, what I learned was precisely not to act like they did. What I learned was to act differently. It’s a very interestingly different lesson that you derive from actors who usually portray heroes that are supposed to be imitated.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Ms. Percy: My favorite scene in the movie comes right before the very end, when Gil Carter, who’s played by Henry Fonda — he reads that letter that Donald Martin wrote to his wife right before he was hung. So he reads it to the men in the bar. After everything has happened, all the men go to the bar to drink. And it’s such a powerful scene, because all we hear is Gil reading the letter. There’s no music. There’s nothing to manipulate us. Just the words.

Mr. Blades: Another great choice. In today’s sensitivities, somebody might just come up with this incredibly huge orchestra. And that’s the dignity that I believe the director — he decided to keep it real and trust his audience. He didn’t feel that the audience had to be manipulated, cued into feeling, as many movies today do.

Ms. Percy: And it’s more powerful because of it.

Mr. Blades: Absolutely.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Mr. Blades: I remember when I saw the movie, in the theater, in the hushed, completely silent, blackout theater, people sobbing. You could actually go to a movie in those days and have audience participation — people cried and laughed and talked back to the screen. And I don’t see much of that now. People do talk a lot now, because they think they’re home.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Exactly, but in a very different way.

Mr. Blades: Yeah, not in a constructive way.

Ms. Percy: No. Well, it’s because a movie was the center of your universe, in a lot of ways. That was where you went to be together, other than church.

Mr. Blades: Absolutely. And also because it was a place that was respected. It was a poor man’s opera. You went there, and you sat down, and you behaved.

Ms. Percy: Yeah. So I mentioned that that was one of my favorite scenes in the film, that previous-to-last scene. And I wonder, what are the scenes that really stand out for you when you think about this movie?

Mr. Blades: I remember that scene that you mentioned, in the bar when he speaks. I remember how angry I got every time that confederate general, whatever he was, ex-general, talked — the hatred he had, the way he treated his son.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Mr. Blades: I remember Anthony Quinn, also, he got shot, and he didn’t complain about it.

Ms. Percy: At all. [laughs]

Mr. Blades: He allows the bullet to be taken out with no anesthesia.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Which I felt a lot of pride: As a fellow Hispanic, I’m like, “That’s right.”

Mr. Blades: He actually does it himself. He actually takes a knife and does it himself, which I thought was really great to have that shown — a character from a minority.

Ms. Percy: A Mexican man, to be the bravest one, in some ways.

Mr. Blades: Yeah, he just took it. Yeah. I guess he’s so accustomed to being violated in so many ways that he didn’t feel that this was any different.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

Ms. Percy: When I think about your career — I grew up listening to your music and being inspired by you as an activist, as someone who fights for what is right and talks about what’s wrong, in your music, as well as in your law and in your politics. And I think about so much of your work being about that justice, that seeking justice for people who’ve been wronged, about how often we are judgmental towards one another.

Mr. Blades: And how many times we are quiet about it.

Ms. Percy: Yes, and how many times we are quiet. And it’s no coincidence to me that you’ve been the opposite of quiet. You’ve stood up and spoken and used your voice in every possible way.

Mr. Blades: It’s interesting, because I don’t portray myself as a hero, I was just upset. I was just angry, actually. And I wrote my songs, always, from the perspective of a different opinion, because I always felt that it made people who were feeling those things feel less lonely. That was basically it. I wanted people to know that they were not alone. That’s what I thought.

Ms. Percy: And I think you gave voice to those who didn’t have a voice in your songs.

Mr. Blades: Well, I was one of the people. Other people did a lot more than I ever did, and some of them were actually killed by the military dictatorships that we were denouncing at the time. Víctor Jara in Chile, he got killed by the military. And in Central America, Monsignor Romero got killed. And the Maryknoll nuns and Rutilio Grande and the Jesuits. There were so many people all throughout, in those days, in Central America and South America, who were being killed for standing up for justice, basically. So I figured, I’m gonna write about that too. And I’m sure that it was a consequence — just as it was for me to go study law, part of it was that desire to prevent the sort of things that I saw when I was very young, exemplified in film.

Ms. Percy: Is there anything else, Rubén, that you’d like to say about Ox-Bow Incident that I didn’t ask you about?

Mr. Blades: I think that it should be the type of film that people see so that we can get acquainted again with our need to be vigilant, so that we do not commit the same mistakes again, especially now, especially in these times that are so troubling, but at the same time, are so promising, I find, because things are being presented for what they are. And that provides us with a perfect opportunity to correct them.

[excerpt: The Ox-Bow Incident]

[music: “Buscando America” by Rubén Blades]

Ms. Percy: Rubén Blades is a Panamanian singer, songwriter, actor, musician, activist, lawyer, politician, and basically my number one hero, besides Captain America. He has too many incredible albums to list, but my favorite is Siembra that he made with Willie Colón. It has “Pedro Navaja,” “Plastico,” all of the songs that made Rubén the legend that he is.

Next time, we’re going to be talking about the badass superhero movie Wonder Woman. If you haven’t seen it, or you just want to revisit it so that you’re feeling strong and empowered for our conversation, you can find it on all the usual streaming sites, or at your local library — the home of some real-life heroes.

This Movie Changed Me is produced by Maia Tarrell, Chris Heagle, Tony Liu, and Marie Sambilay, and is an On Being Studios production. Subscribe to us on Apple Podcasts or wherever you like listening. And if you’re feeling friendly, leave us a review — we love hearing how you’re connecting with the show. Shout-out this week to reviewer “mommabang” who had a different take on our central question — what movie scarred you? She says even the thought of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang terrifies her. For me it would have to be Deliverance. I definitely never looked at Ned Beatty the same way again, and that’s probably where my fear of nature began. Thanks, Deliverance. What are some of the movies that scarred you? Tweet us at @TMCMpodcast, that’s @TMCMpodcast.

I’m Lily Percy. Do yourself a favor and put on some Rubén Blades and dance some salsa tonight.

Reflections