Vincent Harding

Is America Possible?

Vincent Harding was wise about how the vision of the civil rights movement might speak to 21st-century realities. He reminded us that the movement of the ’50s and ’60s was spiritually as well as politically vigorous; it aspired to a “beloved community,” not merely a tolerant integrated society. He pursued this through patient-yet-passionate cross-cultural, cross-generational relationships. And he posed and lived a question that is freshly in our midst: Is America possible?

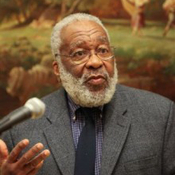

Image by Jason Redmond/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Vincent Harding was chairperson of the Veterans of Hope Project at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. He authored the magnificent book Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement and the essay “Is America Possible?” He died in 2014.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: The conversation I had with Vincent Harding ever after changed the way I think about our democratic experiment. He was a leading figure in the civil rights movement, and he was wise about how the civil rights vision might speak to 21st-century realities. Just as importantly, Vincent Harding pursued this by way of patient yet passionate cross-cultural, cross-generational relationship. The civil rights movement, he reminded us, was spiritually as well as politically vigorous; it aspired to a “beloved community,” not merely a tolerant integrated society. Vincent Harding posed and lived a question that is freshly in our midst again: Is America possible?

Dr. Vincent Harding: How do we work together? How do we talk together in ways that will open up our best capacities and our best gifts? My own feeling that I try to share again and again, Krista, is that when it comes to creating a multiracial, multiethnic, multireligious, democratic society, we are still a developing nation.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Tippett: Vincent Harding was Professor Emeritus of Religion and Social Transformation at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado. I interviewed him in 2011. He died at the age of 82 in 2014. Back in 1955, he was working towards his masters degree in history in Chicago when the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. Eventually, he and a few friends — both Black and white — traveled south to see how they could be of use. Along the way, they paid a life-changing visit to another young man in his late 20s, Martin Luther King Jr.

Vincent Harding says that the phrase “civil rights” never adequately described King’s vision or the human transformation that it stirred. King, for his part, was intrigued by Harding’s work with the Mennonites, one of the original peace churches. And by the early 1960s, Vincent Harding and his late wife, Rosemarie, had moved to Atlanta just around the corner from the Kings. They founded Mennonite House there, which helped the civil rights movement develop its philosophy and its practice of nonviolence.

Tippett: Were you raised Mennonite?

Harding: No, no. I had the marvelous fortune, gift, blessing of being raised by a mother who, shortly after I was born, became a single mother and who had just great hopes for me. And one of the things that my mother wisely did was that she joined a fascinating little church in Harlem called Victory Tabernacle Seventh-Day Christian Church. These were magnificent women and men, a mixture of working class, professional class, all kinds of class. And they loved me, held me, recognized that I had possibilities that I didn’t recognize myself at the outset.

I had to leave them after a while because I’d come to different conclusions than they did. But even after I left, what I found out over the years was that love trumps doctrine every time. And I’m still deeply connected to some of the folks that I grew up with in that church 60, 70 years ago.

Tippett: So, I want to spend most of our time talking about the present day. And I want you to bring the fullness of your moral imagination and spiritual imagination that emerged from all your experiences, including, of course, that and the civil rights movement. For example, one of the words that’s getting tossed around a lot is “civility” and “civil.” I noticed that you’ve stated very emphatically that you think to call that movement, that transformation that you were part of in the 1960s, to reduce it to “civil rights,” “civility” in that case, is not a big enough word. What I’m hearing, as I have in this conversation now, is a lot of people feel like “civility” is not a big enough word for us right now either. So talk to me about that. Do you have any thoughts about that?

Harding: Yes, I think that there are many things that have come to my mind, Krista, during this discussion that’s going on. And, interestingly enough, I hadn’t quite made the connection that you are making now with my own thought, but that’s wonderful. That’s why we need each other. I have felt increasingly that what we are really talking about is not how we can have more civil conversation, but what we’re talking about in the context of our society, for one thing, is how we can learn how to have a democratic conversation. That is what we need.

We are absolutely amateurs at this matter of building a democratic nation made up of many, many peoples, of many kinds, from many connections and convictions and from many experiences. And to know how, after all the pain that we have caused each other, how to carry on democratic conversation that, in a sense, invites us to hear each other’s best arguments and best contributions so that we can then figure out, “How do we put these things together to create a more perfect union?”

Tippett: I found that that way you keep pointing for years, for decades, that asking about how to be democratic is really taking seriously that question of living into a more perfect union. I find that helpful as a way to open that word up.

Harding: For me, Krista, it also opens up the question of, “What does it mean to be truly human?” Democracy is simply another way of speaking about that question. Religion is another way of speaking about that question. What is our purpose in this world, and is that purpose related to our responsibilities to each other and to the world itself? All of that seems to me to be a variety of languages getting at the same reality.

Tippett: Right. And you very strongly make the link in your telling of the story of the civil rights movement, the healing link between religion and democratic transformation. Would you talk to me about that a little bit, about what we’ve forgotten about the spiritual and religious dimensions of that?

Harding: Let’s remember, Krista, that that community that helped to create King, and that he then helped to nurture, was a community deeply grounded in the life of religion and spirituality. This was their way of being. For instance, everyone near him knew that he took very seriously this traditional, beautiful terminology when he said that what he was seeking for was not simply equality or rights, but what he was seeking for was the creation of the beloved community, that he saw everything that crushed against our best human development and our best communal development, like segregation, like white supremacy.

When he moved to break down those laws, those practices, he was doing it not simply as an act of civil action, but a deep spiritual responsibility. Seeing our best possibilities, like my church community saw in me, he saw it in this nation. People like Jimmy Baldwin and others, Malcolm, for a certain time, couldn’t imagine how Martin could see those possibilities. But I think he was seeing it because he was looking with an eye that was deeply filled by love and compassion, and that eye opens us up to see many things that might otherwise be missed.

[music: “Woke Up This Morning” by John Legend]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, summoning the wisdom for now of the late civil rights elder Vincent Harding.

In the decades after the 1960s, Vincent Harding wrote a seminal book, Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement. And he began to bring young people together with elders of the movement. He founded the Veterans of Hope Project at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver to institutionalize this work in creative ways. Most riveting and instructive for the young, as Vincent Harding told it, are stories of how civil rights leaders have worked on society while at the same time constantly working on themselves.

[music: “Woke Up This Morning” by John Legend]

Tippett: This idea of storytelling and the importance of stories just for human beings in general, but in a moment like this in particular, comes up so much. And yet, I feel like we don’t — I don’t know if we don’t have the forms for it in this culture or if it’s happening under the surface and not being pointed at. I mean, you are doing this.

Harding: My own sense, Krista, is that there is something deeply built into us that needs story itself. That story is a source of nurture that we cannot become really true human beings for ourselves and for each other without story. And to find ways in which to tell it, to share it, to create it, to encourage younger people to create their own story.

For instance, in the work that we do with the Veterans of Hope, we also encourage the younger people to find the elders, to find the veterans, not the celebrities, not the TV stars, but those folks who nobody else knows have lived such magnificent lives. Find them, and then sit with them, and learn how to ask the right questions so that the opening can take place. I think that this country cannot become its best self until we find ways more effectively of institutionalizing that process of sharing the stories of the elders.

Tippett: When you say that we, as human beings, have a built-in need for stories, what your work shows is that we human beings also know what to do with stories, right? So that, as you say, the young people you work with know to take those stories as tools and pieces of empowerment in this day, this year.

Harding: For their own best work. Because now, it’s a powerful time in this country for young people and others to be asking the question, “And what are we for?” Do we exist for some reason other than competing with China or finding the best possible technological advances? Are there some things that are even deeper that we are meant for, meant to be, meant to do, meant to achieve? Jimmy Baldwin used to like to talk about us achieving ourselves, finding who we are, what we’re for, and making that possible for each other.

So you’re right about — the story — just as you were speaking, what I was thinking about, Krista, was when the mother with the baby at her bosom starts telling stories is clearly not just to pass on information. What I find is that, even in some of the strangest situations, most often where I go, where I speak, where I share, I start out by asking people to tell a little of their stories. And it is amazing what people discover of themselves, of their connections, of their community. It’s wonderful.

Tippett: You know, I’ve learned that too. To ask someone even to tell a little of their story is to give them a gift because we don’t get asked that question. And we do learn as much as we tell. You wrote a very important book, Hope and History. 1990, I believe?

Harding: Yeah, I think that was about the time.

Tippett: You must have been writing in the ’80s. There’s a story you tell that, again, I felt offered up a really practical image for now. It’s about your conversation, encounter, you were having in a hard neighborhood in Boston and — a young man named Darryl. Would you tell that story about signposts, his image of signposts?

Harding: What I remember from that story was that a dear young friend of mine, Eugene Rivers, young at that time — I guess Gene’s going to feel old.

Tippett: Still busy in Boston.

Harding: Still busy in Boston. That, by the way, is one of the characteristics of many of the elders that we have interviewed in the Veterans Project, that people are persistent, that they go on and on and on, something that is not appreciated in this sound bite society. If you don’t get it told, done, accomplished in 10 minutes or 10 days or even 10 years, then you’ll surely give up and turn away.

But people like Gene and others — Grace Boggs is one of the great women who came out of a Chinese ancestry, first generation in this country, married eventually a Black man from Alabama who was a union organizer in Detroit. And the two of them, Grace and Jimmy Boggs, became a tremendous team until Jimmy died some years ago. Grace is now 95 and, in Detroit, she is one of the primary encouragers of the young people there not to be swept away by all of the talk about the end of Detroit, about the failures of Detroit. But she is working with young people to help them to become those who build again, create again.

[music: “When I Die (You Better Second Line)” by Kermit Ruffins]

Harding: Well, all of that takes us away from the story, but also illustrates a story.

Tippett: [laughs] It does. Yeah.

Harding: I met this young man in Eugene’s apartment, and this young man came up just to sit next to me because he wanted to talk in a more personal way. It turned out that he was one of the leaders of the drug-running folks at the time. But what he said to me was that he really felt that one of the reasons why he had gone in the way that he had gone — not trying in any way to excuse himself — was the fact that he, like many other young people, were operating in a situation where they felt it was just very, very dark all around them. And what they needed were, as he put it, some signposts, some lights that would, in other peoples’ lives, help them…

Tippett: “Live human signposts,” you wrote.

Harding: Yes, yes. That would help them to see the possibilities for themselves. I’ve always felt that one of the things that we do badly in our educational process, especially working with so-called marginalized young people, is that we educate them to figure out how quickly they can get out of the darkness and get into some much more pleasant situation when what is needed again and again are more and more people like Gene who will stand in that darkness, who will not run away from those deeply hurt communities, and will open up possibilities that other people can’t see in any other way except seeing it through human beings who care about them. And if we teach young people to run away from the darkness rather than to open up the light in the darkness, to be the candles, the signposts, then we are doing great harm to them and the communities that they have come out of.

Tippett: I think this word “signpost” and this image of signpost is really important. I think it’s an important piece of practical vocabulary. You said a minute ago about elders, that what you also tell young people is that they have to find the elders, right? I’ve thought a lot over the years about the teaching in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament that I think has resonance across the traditions of developing eyes to see and ears to hear. I think that is almost a spiritual discipline that the 21st century makes more necessary.

Harding: That whole idea of discipline is one that clearly we have cast aside except when we’re talking about technological development or military development. And it seems to me that we need, again, to recognize that to develop the best humanity, the best spirit, the best community, there needs to be discipline, practices of exploring. How do you do that? How do we work together? How — to go back to our conversation — how do we talk together in ways that will open up our best capacities and our best gifts?

My own feeling that I try to share again and again, Krista, is that when it comes to creating a multiracial, multiethnic, multireligious, democratic society, we are still a developing nation. We’ve only been really thinking about this for about half a century. But my own deep, deep conviction is that the knowledge, like all knowledge, is available to us if we seek it.

The older I get, the more I am convinced that that magnificent madman, Jesus, was really talking about something very truthful and powerful when he said if you allow yourself to really hunger and thirst after the right way, then if you will not back off from that hunger and that thirst, if you will just keep after it, then you will find the way. You will be filled. The way will find you. I think that that determination to find a truly democratic society and to create the truly beloved community, those are things that can be available to us if we’re willing to work with each other and work with the universe on developing them. They don’t come free and easy. They are tough, tough tasks for us to take on.

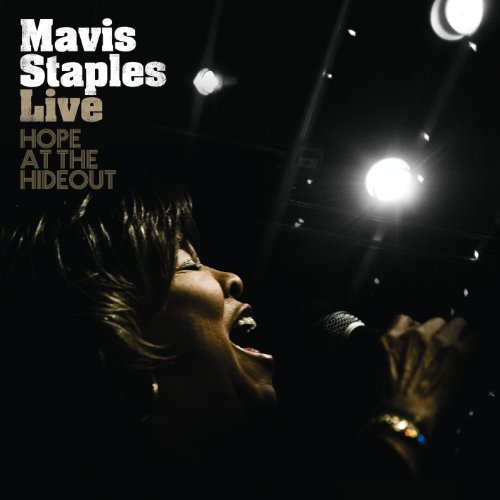

[music: “We Shall Not Be Moved” by Mavis Staples]

Tippett: That’s the voice of Mavis Staples, one of the people who, as Vincent Harding described it, “sang the way to freedom” in the 1960s.

After a short break, more with Vincent Harding. You can always listen again, and hear the unedited version of every show we do on the On Being podcast feed — wherever podcasts are found.

[music: “We Shall Not Be Moved” by Mavis Staples]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “We Shall Not Be Moved” by Mavis Staples]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today, summoning the wisdom of the late civil rights elder Vincent Harding. He was a leading figure in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. He was also a close friend and occasional speechwriter to Martin Luther King Jr. Vincent Harding posed and lived a question that is freshly in our midst again: “Is America possible?”

Tippett: That question, “How do we do it?” is absolutely the question that I think is rising to the surface past our calls for civil discourse, moral imagination. But some of the tools you offer up, some of the answers to that question, are also quite wonderful. I mean, the discipline is mixed with the arts and creativity, right? I mean, you talk about your memory of those years of the ‘60s, that hard fight that also contained so much violence and darkness. You say you have a memory of people singing their freedom.

Harding: Yes. Tremendous creativity, that’s — I go back to some of the old Black preachers, speakers, practices, by putting letters and words together. When I think about Martin, I think about Martin with the three C’s: courage, compassion and creativity. And I think that the stoking of our creative capacities is one of the jobs that is still necessary for us. I’m always talking to my young hip-hop — young people about the fact that we need some new songs from the hip-hop generation that will speak about the beloved community in whatever terminology they choose now. But we need some music that people can join together in to express their great need and desire for a better world.

Tippett: Do they engage you in that conversation?

Harding: Oh, yes, they do. We have a fantastic time as we try to figure out, “And now, what are the new songs, and what are the new words?” For instance, let me just mention one word that we’ve been working with lately. I’ve been on a campaign encouraging people as we think about the beloved community to stop using this word “minority,” that there is something negative about that terminology because it always suggests that somebody else is the majority. The fact is, we are all now creating a new majority. We are all part of this beloved community. In community, the concept of minority simply doesn’t work. You don’t have a minority in a family. So we have got to get new words, new songs, new possibilities for ourselves.

Tippett: And, again, that phrase “beloved community” was this phrase from the gospel, which Martin Luther King used so evocatively to describe the community of the civil rights movement. You wrote about how “This Little Light of Mine” was sung at Selma. Rather than saying, “Governor Wallace, give us our freedom,” it was about singing, “This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine.”

Harding: That was so much part of the way in which the songs try to encourage us not simply to be reactors. So that instead of saying, “You honky governor, you’re no good, and we’re gonna do this or that to you,” the basic, deepest word was, “Whatever you do, we’re gonna let our light shine. God gave it to us. We’re gonna let it shine,” was the way that the words went. That determination to make our own action and our own commitment the focal point rather than a reaction to the moves of others was, I think, one of the most beautiful things about the singing.

[music: “This Little Light of Mine” by Betty Mae Fikes]

Tippett: This is the voice of Betty Mae Fikes, a teenager at the time and one of the Freedom Singers — the music arm of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The year this was recorded, 1963, she spent three weeks in jail for singing during the civil rights struggles in Selma.

[music: “This Little Light of Mine” by Betty Mae Fikes]

Harding: Let me mention another of those songs that recently came up in a New York Times article. I don’t know if you saw this. Someone was writing about this terminology that we’ve taken about a “Kum Bah Ya” moment, where we have made fun, in a way, of this whole experience that came out of the Black church of the singing of that song.

Whenever somebody jokes about “Kum Bah Ya,” my mind goes back to the Mississippi summer experience where the movement folks in Mississippi were inviting co-workers to come from all over the country, especially student types, to come and help in the process of voter registration, and Freedom School teaching, and taking great risks on behalf of the transformation of that state and of this nation. There were two weeks of orientation. The first week was the week in which Schwerner and Goodman and their beloved brother Jimmy were there. And it was during the time that they had left the campus that they were first arrested, then released, and then murdered.

The word came back to us at the orientation that the three of them had not been heard from. Bob Moses, the magnificent leader of so much of the work in Mississippi, got up and told these hundreds of predominantly white young people that, if any of them felt that at this point they needed to return home or to their schools, we would not think less of them at all, but would be grateful to them for how far they had come.

But he said let’s take a couple of hours just for people to spend time talking on the phone with parents or whoever to try to make this decision and make it now. What I found as I moved around among the small groups that began to gather together to help each other was that, in group after group, people were singing “Kum Bah Ya.” “Come by here, my Lord, somebody’s missing, Lord, come by here. We all need you, Lord, come by here.”

I could never laugh at “Kum Bah Ya” moments after that because I saw then that almost no one went home from there. They were going to continue on the path that they had committed themselves to. And a great part of the reason why they were able to do that was because of the strength and the power and the commitment that had been gained through that experience of just singing together “Kum Bah Ya.”

[music: “Come By Here” by Sweet Honey in the Rock]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, summoning the wisdom for now of the late civil rights elder Vincent Harding. He was a pivotal figure in that movement of the 1960s and he worked to bring its lessons usefully and creatively to young people and the rest of us in the present day.

[music: “Come By Here” by Sweet Honey in the Rock]

Tippett: I was listening to the BBC in recent weeks, and they’re watching us from afar. They were interviewing a journalist about this moment in American history, which seems very tumultuous and the question was, “Is it really more violent and more despairing than it’s been before or does this happen repeatedly?” And the comparison was made with the 1960s.

They said, look, there was a lot of social turmoil then. There were assassinations, right? I mean, many assassinations. But this journalist said — and I just want to know what you think — he said that he thought the difference between the 1960s and now was that even though there was incredible tumult and violence, it was at the very same time a period of intense hope, and people could see that they were moving towards goals. And that that’s missing now. What do you think about that analysis?

Harding: Hmm. Krista, I think that is such a complicated kind of issue that I can only pick at it and tease it out and play with it in the best sense of play. I think that what I see now is the fact that all over this country, wherever I go, and, of course, where I go tends to be sort of self-selective because I am most often going into situations where people are operating out of a sense of hope and possibility, where in their local situations, whether it be Detroit, or Atlanta, or a campus someplace, or a church community in Philadelphia, that there are women and men and young people who are operating out of hope.

My sense is that, in the ‘60s, there was probably a larger kind of canopy of hope that we could see, and we could identify, and that people could name and focus on. Now, we are in particular spots, locations, sometimes seemingly isolated. But I feel that there are points, focal situations, where that is still available and where people are operating from that.

So I think that it is not simply the matter of hope or no hope. I have a feeling that one of the deeper transformations that’s going on now is that for the white community of America, there is this uncertainty growing about its own role, its own control, its own capacity to name the realities that it has moved into a realm of uncertainty that it did not allow itself to face before.

And I think that that’s the place that we are in, and that’s even more the reason why we’ve got to figure out what was King talking about when he was seeing the possibility of a beloved community and recognized that, maybe, for some of us, that cannot come until some of us realize that we must give up what we thought was only ours in the building of a beloved nation. Can there be a beloved nation? Why don’t we try and see?

[music: “My Country Tis of Thee” by Rene Marie]

Tippett: There’s a question that you pose in your writing, that you’ve posed in recent years, “Is America possible?” which kind of echoes back to your assertion that we need more than civil discourse now. We need to more fully realize what it means to be a democracy. I just wonder, when you answer that question, “Is America possible?” what people come to mind? What answers come to mind in the form of the hope that you see embodied?

Harding: One of the great benefits of living almost to my 80th birthday is the great privilege of being able to meet and be with all kinds of marvelous people. I spend a lot of my time in places like Philadelphia where, on the northwest side, I’ve been deeply involved with a church community there, a Methodist church led by a magnificent woman pastor who has embraced the young people of the community in ways that churches often do not. Young people who were considered marginalized have become the heart of her work, and they have seen their own possibilities.

I remember when a group of them came out to visit us at our project in Denver. They were true Philadelphians. They were dressed from the Philadelphia streets, they moved like Philadelphians, and they ran into some very interesting encounters in Denver. But at one point, two of them — one young man, one young woman — took me aside and said, “Could we talk to you for just a minute?” They had started to call me Uncle Vincent, and they said to me, “Uncle Vincent, why do you love us so?” And what I saw was that they had this great capacity to know that they were being loved, to feel it in their being, and through later conversation that we had, to recognize that that meant they had power and responsibility to do something for their community that had not been done for them.

I see young people like that all over this country, and I know that they exist. I know some of the adults who work with them in places like Greensboro, North Carolina; in Detroit, Michigan; on the reservations in New Mexico; out in the LA area. We’ve got working connections with young people and their adult nurturers in all of those kinds of situations. Because I see that, feel that, receive their returning love, I know they are capable of building the beloved community.

And so it is that kind of constant engagement with people who have been considered hopeless, useless, purposeless, just like I saw them in the Deep South. People who were considered backward, unable to do anything, became the creators of a new possibility for the whole nation. And when I think about Tiananmen Square and Prague, I realize that those folks in Mississippi and Alabama who were considered useless were able to speak to the world. I see that again and again and again right in this country, see it with young people, see it with those who are loving them into new possibilities. And so that’s why, for me, the only answer that I can give to the question that I raise is, yes, as we make it possible, yes, yes.

[music: “This Little Light of Mine” by Carlton Reese Memorial Unity Choir]

Tippett: Vincent Harding was chairperson of the Veterans of Hope Project at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. He was also Professor of Religion and Social Transformation there. He died surrounded by family and friends on May 19, 2014. In his lifetime, he published wonderful writings, including his book Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement and his essay, “Is America Possible?”

At veteransofhope.org, you can delve into a repository of Vincent Harding’s interviews of his fellow elders, the leading women and men of the civil rights movement.

[music: “This Little Light of Mine” by Carlton Reese Memorial Unity Choir]

The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, and Jhaleh Akhavan

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections