Civil rights legend Ruby Sales learned to ask “Where does it hurt?” because it’s a question that drives to the heart of the matter — and a question we scarcely know how to ask in public life now. Sales says we must be as clear about what we love as about what we hate if we want to make change. And even as she unsettles some of what we think we know about the force of religion in civil rights history, she names a “spiritual crisis of white America” as a calling of today.

Wise Elders

Featured Items

Vincent Harding was wise about how the vision of the civil rights movement might speak to 21st-century realities. He reminded us that the movement of the ’50s and ’60s was spiritually as well as politically vigorous; it aspired to a “beloved community,” not merely a tolerant integrated society. He pursued this through patient-yet-passionate cross-cultural, cross-generational relationships. And he posed and lived a question that is freshly in our midst: Is America possible?

View

- List View

- Standard View

- Grid View

28 Results

Filters

December 12, 2024

Remembering Nikki Giovanni — ‘We Go Forward With a Sanity and a Love’

The delightful Nikki Giovanni died on Dec. 9. It is a joy and a solace to relisten to this beloved conversation she had with Krista in 2016 – to experience her signature mix of high seriousness, sweeping perspective, and insistent pleasure. Her words and her spirit feel, if anything, more necessary now. In the 1960s, she was a poet of the Black Arts Movement that nourished civil rights. She became a professor at Virginia Tech, where she called forth beauty and courage after the 2007 shooting there — a precursor to violence that has become all too familiar in American life in the intervening years. And she was an adored voice to a new generation — an enthusiastic elder to all — at home in her body and in the world, even while she saw and exulted in the beyond of this tumultuous age of her lifetime.

She is known as the voice of a generation. The Queen of Folk. A legend. An icon, the one who sang “We Shall Overcome” alongside Martin Luther King Jr. at the 1963 March on Washington. As much as anyone, Joan Baez embodied the spirit of that decade of soaring dreams and songs and dramas set in motion that echo through this world of ours. Meanwhile, her love affair with a young Minnesota singer-songwriter calling himself Bob Dylan, whose career she pivotally helped launch, is also reentering the public imagination with a big new movie. And her classic heartbreak hit about him, “Diamonds and Rust,” is topping global charts anew.

But Joan Baez at 83 is so much more intriguing than her projection as a legend. She grew up the daughter of a Mexican physicist father and a Scottish mother in a seemingly idyllic family. But even at the height of her fame, she was struggling mightily with mysterious interior demons. She and her beloved sisters finally reckoned in midlife with a truth of abuse they had buried, even in memory, at great cost. She has reckoned with fracture inside herself and been on an odyssey of wholeness. She is frank and funny, irreverent and wise. Among other gifts, she offers a refreshing way in to what it means to sing and live the reality of “overcoming,” personal and civilizational.

Krista spoke with Joan — who has recently published her first book of poetry — on stage at the 2024 Chicago Humanities Festival.

May 23, 2024

Lyndsey Stonebridge and Lucas Johnson

On Love, Politics, and Violence (Channeling Hannah Arendt)

Here is a stunning sentence for you, written by Lyndsey Stonebridge, our guest this hour, channeling the 20th-century political thinker and journalist Hannah Arendt: “Loneliness is the bully that coerces us into giving up on democracy.” This conversation is a kind of guide to generative shared deliberations we might be having with each other and ourselves in this intensely fraught global political moment: on the human underlay that gives democracy its vigor or threatens to undo it; on the difference between facts and truth — and on the difference between violence and power. Krista interviewed Lyndsey once before, in 2017, after Hannah Arendt’s classic work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, had become a belated runaway bestseller. Now Lyndsey has published her own wonderful book offering her and Arendt’s full prescient wisdom for this time. What emerges is elevating and exhilaratingly thoughtful — while also brimming with helpful, practicable words and ideas. We have, in Lyndsey’s phrase, “un-homed” ourselves. And yet we are always defined by our capacity to give birth to something new — and so to partake again and again in the deepest meaning of freedom.

Hannah Arendt’s other epic books include The Human Condition, and Eichmann in Jerusalem, in which she famously coined the phrase “the banality of evil.” She was born a German Jew in 1906, fled Nazi Germany and spent many years as a stateless person, and died an American citizen in 1975. This conversation with Lyndsey Stonebridge happened in January 2024, as part of a gathering of visionaries, activists, and creatives across many fields. Krista interviewed her alongside Lucas Johnson, a former leader of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation who now leads our social healing initiatives at The On Being Project.

“I like it much better than ‘religious’ or ‘spiritual’ — to be a seeker after the sacred or the holy, which ends up for me being the really real.”

– Rev. Barbara Brown Taylor

From Krista, about this week’s show:

It’s fascinating to trace the arc of spiritual searching and religious belonging in my lifetime. The Episcopal priest and public theologian Barbara Brown Taylor was one of the people I started learning about when I left diplomacy to study theology in the early 1990s. At that time, she was leading a small church in Georgia. And she preached the most extraordinary sermons, and turned them into books read far and wide. Then in 2006, she wrote Leaving Church — about her decision to leave her life of congregational ministry, finding other ways to stay, as she’s written, “alive and alert to the holy communion of the human condition, which takes place on more altars than anyone can count.”

She’s written other books since, with titles like An Altar in the World, Learning to Walk in the Dark, and Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others. Being in the presence of Barbara Brown Taylor’s wonderfully wise and meandering mind and spirit, after all these years of knowing her voice in the world, is a true joy. I might even use a religious word — it feels like a “blessing.” And this is not a conversation about the decline of church or about more and more people being “spiritual but not religious.” We both agree that this often-repeated phrase is not an adequate way of seeing the human hunger for holiness. This is as alive as it has ever been in our time — even if it is shape-shifting in ways my Southern Baptist and Barbara’s Catholic and Methodist forebears could never have imagined.

To say that Ruth Wilson Gilmore is a geographer, which she is, is not to convey the vast and varied ways in which she is influencing the makings of the future. She’s a mentor and teacher to a new generation of social activism and creativity. She’s a visionary of “abolition,” and that has become a fraught and polarizing word in our fraught and polarized public discourse. But when Ruth Wilson Gilmore speaks of “abolition,” she is working with a long, long view towards making a whole world, starting now, in which prisons and policing as we do them now become unnecessary, unthinkable. In this sense, abolition is not primarily a matter of what to get rid of, but what to build and to orient around — being present, for example, to human vulnerability and to the ingredients that make for deep human flourishing.

Meeting Ruth Wilson Gilmore and drawing her out in this way is an exercise in muscular hope — and in understanding the passion of a new generation that is shaping what we will collectively become.

A few years ago, Krista hosted an event in Detroit — a city in flux — on the theme of raising children. The conversation that resulted with the Jewish-Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist Sylvia Boorstein has been a companion to her and to many from that day forward. Here it is again as an offering for Mother’s Day — in a world still and again in flux, and where the matter of raising new human beings feels as complicated as ever before. Sylvia gifts us this teaching: that nurturing children’s inner lives can be woven into the fabric of our days — and that nurturing ourselves is also good for the children and everyone else in our lives.

“Prayers are tools not for doing or getting, but for being and becoming.” These are words of the late legendary biblical interpreter and teacher Eugene Peterson. At the back of the church he pastored for nearly three decades, you’d be likely to find well-worn copies of books by Wallace Stegner or Denise Levertov. Frustrated with the unimaginative way he found his congregants treating their Bibles, he translated the whole thing himself and that translation has sold millions of copies around the world. Eugene Peterson’s literary biblical imagination formed generations of pastors, teachers, and readers. His down-to-earth faith hinged on a love of metaphor and a commitment to the Bible’s poetry as what keeps it alive to the world.

The remarkable Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town and Nobel Laureate died in the closing days of 2021. He helped galvanize South Africa’s improbably peaceful transition from apartheid to democracy. He was a leader in the religious drama that transfigured South African Christianity. And he continued to engage conflict well into his retirement, in his own country and in the global Anglican communion. Krista explored all of these things with him in this warm, soaring 2010 conversation — and how Desmond Tutu’s understanding of God and humanity unfolded through the history he helped to shape.

Jane Goodall’s early research studying chimpanzees helped shape the self-understanding of our species and recalled modern Western science to the fact that we are a part of nature, not separate from it. In honor of the publication of her 32nd book — The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times — we’re re-releasing her beautiful conversation with Krista over Zoom from pandemic lockdown. From her decades studying chimpanzees in the Gombe forest to her more recent years attending to human poverty and misunderstanding, the legendary primatologist reflects on the moral and spiritual convictions that have driven her, and what she is teaching and still learning about what it means to be human.

The classic economic theory embedded in western democracies holds an assumption that human beings will almost always behave rationally in the end and make logical choices that will keep our society balanced on the whole. Daniel Kahneman is the psychologist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics for showing that this is simply not true. There’s something sobering — but also helpfully grounding — in speaking with this brilliant and humane scholar who explains why none of us is an equation that computes. As surely as we breathe, we will contradict ourselves and confound each other.

January 18, 2021

Living the Questions

A Civil Rights Elder on Exhaustion and Rest, Spiritual Practice, and the Necessity of Loving Community

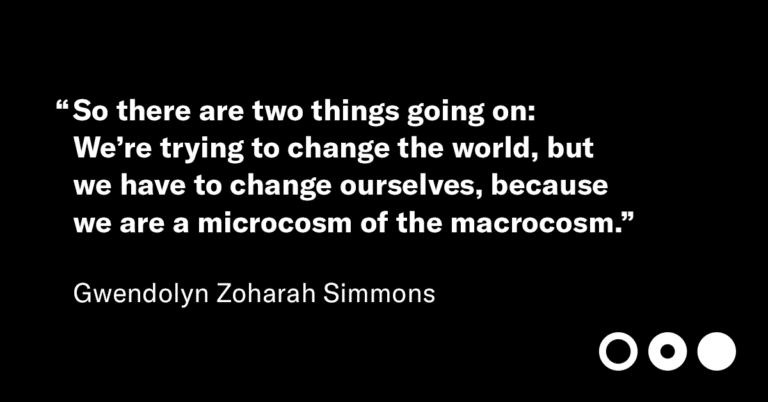

Our colleague Lucas Johnson catches up with one of his mentors, Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons. Now a member of the National Council of Elders, she was a teenager when she joined the Mississippi Freedom Summer. She shares what she has learned about exhaustion and self-care, spiritual practice and community, while engaging in civil rights organizing and deep social healing. Dr. Simmons was raised Christian and later converted to the Sufi tradition of Islam.

December 31, 2020

Mary Catherine Bateson

Living as an Improvisational Art

Underpinning all the great challenges of our time there is the human drama, the human condition. And as we move beyond 2020, we turn to Mary Catherine Bateson to help us understand the puzzle of being ourselves, of rising to our best capacities and gifts, in all of our complexity and strangeness. She is the daughter of the great anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, and she is a linguist and anthropologist herself.

Marilyn Nelson is a storytelling poet. She has taught poetry and contemplative practice to college students and West Point cadets. She brings a contemplative eye to ordinary goodness in the present and to complicated ancestries we’re all reckoning with now. And she imparts a spacious perspective on what “communal pondering” might mean.

An extraordinary conversation with the late congressman John Lewis, taped in Montgomery, Alabama, during a pilgrimage 50 years after the March on Washington. It offers a special look inside his wisdom, the civil rights leaders’ spiritual confrontation within themselves, and the intricate art of nonviolence as “love in action.”

Pauline Boss coined the term “ambiguous loss” and invented a new field within psychology to name the reality that every loss does not hold a promise of anything like resolution. Amid this pandemic, there are so many losses — from deaths that could not be mourned, to the very structure of our days, to a sudden crash of what felt like solid careers and plans and dreams. This conversation is full of practical intelligence for shedding assumptions about how we should be feeling and acting as these only serve to deepen stress.

Vincent Harding was wise about how the vision of the civil rights movement might speak to 21st-century realities. He reminded us that the movement of the ’50s and ’60s was spiritually as well as politically vigorous; it aspired to a “beloved community,” not merely a tolerant integrated society. He pursued this through patient-yet-passionate cross-cultural, cross-generational relationships. And he posed and lived a question that is freshly in our midst: Is America possible?

Civil rights legend Ruby Sales learned to ask “Where does it hurt?” because it’s a question that drives to the heart of the matter — and a question we scarcely know how to ask in public life now. Sales says we must be as clear about what we love as about what we hate if we want to make change. And even as she unsettles some of what we think we know about the force of religion in civil rights history, she names a “spiritual crisis of white America” as a calling of today.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu is one of our wisest models on the territory of reckoning with past wrongs that infuse and haunt the present. In the 1990s, he helped galvanize South Africa’s peaceful transition to democracy after decades of white supremacy as the law of the land. He tells a story of how healing and human redemption unfold from his time chairing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which granted amnesty to those who would fully confess their crimes. “Human beings can leave you speechless, really. They can leave you speechless by the horrible things they do, but they also leave you speechless with the incredible things,” he says.

The Pause

Join our constellation of listening and living.

The Pause is a monthly Saturday morning companion to all things On Being, with heads-up on new episodes, special offerings, event invitations, recommendations, and reflections from Krista all year round.

Search results for “”

View

- List View

- Standard View

- Grid View

Filters