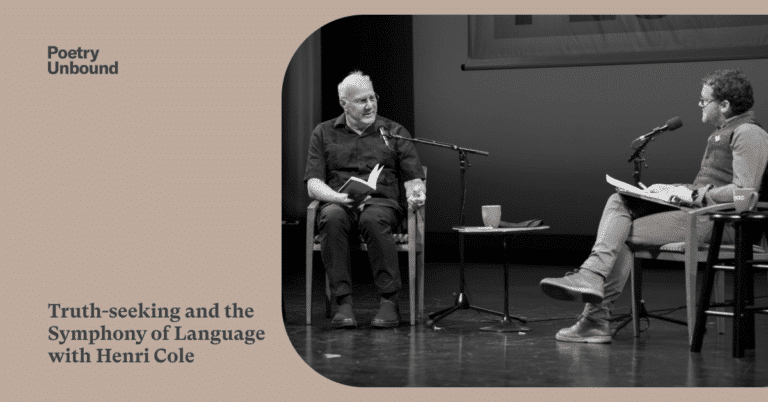

BONUS: Truth-seeking and the Symphony of Language with Henri Cole

A central duality appears in the work of Henri Cole: the revelation of emotional truths in concert with a “symphony of language” — often accompanied by arresting similes. We are excited to offer this conversation between Pádraig and Henri, recorded during the 2022 Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark, New Jersey. Together, they discuss the role of animals in Henri’s work, the pleasure of aesthetics in poetry, and writing as a form of revenge against forgetting.

Image by Alex Towle Photography, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Henri Cole was born in Fukuoka, Japan and raised in Virginia. He has published many collections of poetry and received numerous awards for his work, including the Jackson Poetry Prize, the Kingsley Tufts Award, the Rome Prize, the Berlin Prize, the Ambassador Book Award, the Lenore Marshall Award, and the Medal in Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His most recent books are a memoir, Orphic Paris (New York Review Books, 2018), Blizzard (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), and Gravity and Center: Selected Sonnets, 1994-2022 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023). From 2010 to 2014, he was poetry editor of The New Republic. He teaches at Claremont McKenna College and lives in Boston. Image: © Claudia Gianvenuti for the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, 2009.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Hi friends, thanks very much for listening to Poetry Unbound. Season 7 is finished, and season 8 is going to be coming out in the winter. And in the meanwhile, in between these seasons, we’re going to be releasing a few interviews that I did last year at the 2022 Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark in New Jersey in the States. It was a great time to be there. Thanks very much to Martin Farawell and everybody else involved in that festival for the invitation and the warm welcome. I know you’ll enjoy these interviews. It was a thrill to make them.

This interview is with sonnet writer extraordinaire, Henri Cole. If you want to keep in touch with things Poetry Unbound you can sign up for the weekly free Substack. I write a reflection on a poem and offer a question and people respond to that every week on a Sunday. So keep in touch, and looking forward to season 8, and all the best.

Ó Tuama: Good afternoon, everybody. You’re all very welcome to the Victoria Theater at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center for Dodge 2022. It’s a great joy to be with you. My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama from Poetry Unbound with On Being, and it is my real honor to be in conversation today with Henri Cole. I am delighted to have the opportunity for us to hear some of his poetry and to engage in some of your craft and language. You can find a fuller intro to Henri in your schedule and in your program. But there you’ll hear about his 10 collections, his many prizes, the Kingsley Tufts Award, the Rome and Berlin Prizes, the Lenore Marshall Award. Also, about his most recent collection, Blizzard, which was published in 2020, and in April 2023, Gravity and Center, which is a selection of his sonnets, will be released. Henri has been poetry editor for a New Republic, has taught at Ohio State University and Harvard and Yale, and currently teaches at Claremont McKenna in Boston, which is where he — Well, I’m not sure where that is. I know you live in Boston, I’m assuming that Claremont McKenna is somewhere nearby.

Henri Cole: No, it’s in California.

Ó Tuama: Is that right? There we are, haven’t a clue. I should have checked that out.

[laughter]

Cole: Yeah, it’s in California.

Ó Tuama: So, I want to honor you with your own words back to you before we start, Henri. Your capacity to shock with visceral, sensuous, and sometimes consoling language overwhelmed me as I’ve been preparing for this. These two similes are from the one poem called “Childlessness,” which is in The Visible Man published in 1998. “I believe[d]/ that happiness would at last assert itself, like a bird in a dirty cage, calling me, / ambassador of flesh, out of the rough / locked ward of sex.” And then later on in the same poem, as if that wasn’t enough, “When you died, Mother, / I was alone at last. And then you came / back, dismal and greedy like the sea, to reclaim me.” We are in the hands and in the sonic company of a poet with an extraordinary capacity for a language and for seeking truth through language. So please everybody give a warm welcome to Dodge 2022 to Henri Cole.

[applause]

Cole: Thank you. Thank you.

Ó Tuama: Just by way of a bit of a landscape about how we’re going to do this: Henri and I are going to be in conversation and there’ll be various poems recited throughout, and then there’ll be some Q and A toward the end. There’s mics at the front, you can come forward for that, and you can be preparing a short question throughout the next 55 minutes, and then we’ll bring it back up on stage to finish it off for the final poem and a final few words from Henri.

Cole: Maybe we should tell them that we have just met.

Ó Tuama: Yeah, yeah. We’ve been emailing for a few weeks but have never met in person. I’m curious, is there an early poet whose work captured you, or perhaps even just an early poem early in your life?

Cole: Well, I’m just now teaching a gay poetry seminar, and all the poets that I’m teaching I didn’t read early in my life, but they were my first loves. And one of them is Cavafy, Constantine Cavafy. And those poems are 100 years now, but they read like contemporary poems. I don’t think that’s just because they’re recent translations necessarily. But I was very drawn to the idea that something was being revealed that hadn’t been known. And to the element of surprise, and to speaking in a vernacular voice, though it isn’t really vernacular at all.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. What did Cavafy speak to the gut of you? Why did it connect with you?

Cole: Well, I suppose it was secret desire. Secret desire between men, sometimes men of different classes. It was the idea of the taboo, something that is unspoken. Though reading these poems with my students now, they point out to me that the gender of the beloved is not always identified necessarily, so one makes a lot of inferences reading the poems. But that was part of the excitement for me, I think. But there were many poets, Hart Crane, Hopkins, even someone like Langston Hughes, or Elizabeth Bishop. I was drawn to the idea that much is contained. Even though those examples reveal a great deal, I like the idea of something being contained and that something is usually the unspeakable, the taboo.

Ó Tuama: I read that you said once that in your earlier work that you hid behind nature, and it’s not that nature isn’t present as your work has continued, but are you using it in a different way now?

Cole: Well, I suppose I am. I think that when you write using animals or characters in myth or fairytale, often you can use them as a mask and you can actually go farther than speaking autobiographically. So I was drawn to that technique. Certainly, I didn’t come out — I’m 66, I published my first book when I was 30. And I came out when I was 30, actually, which is probably unbelievably late now, but for a southern boy, 40 years ago, it wasn’t so late. I still use animals, I’ve been translating the fables of Jean de La Fontaine and hope that will be my next book. In his case, he uses the animals to sort of satirize human nature, which is one of the functions. I don’t really use them to satirize so much as I do to reveal qualities between humans.

Ó Tuama: And in terms of those poets that you mentioned that you turned to in earlier life, was it secrecy also as well as something being concealed? Was it the level of secrecy that they were forced to be under by a society that wouldn’t have tolerated their full story in public?

Cole: Well, I think in each one it was something a little different, and someone like Hart Crane, I like this sort of high voltage language that was almost operatic, you might say, and yet strictly hidden, you might say, about desire. And I think that is one way of responding. I’m still drawn to that, actually. We live in a moment of high praise for accessibility, but I don’t think that that is — I think that can be overdone.

As a reader, I like to feel like I’m somewhere other than conversation in a poem. Even in someone like Langston Hughes, who wasn’t really out in his poetry, and he saw that solution by writing from the voice of a woman in many of his poems. A woman to a man. Even in his poems, which are utterly vernacular, he rhymes so much that you know he wants to remind you that you’re not in just demonic language, vernacular speech, you’re in art. You’re in a poem. And I believe in that.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: I want my poems to sound effortlessly spoken, but they’re obviously — If I was speaking to you over lunch and I proceeded to speak them as sentences, you would think I was rather odd. But in a poem they can be —

Ó Tuama: It can work.

Cole: Yeah.

Ó Tuama: Well, in a while I’m curious to ask you a bit about the presence of you in the poem, because on the one hand you display yourself, and on the other hand, you always seem to point away from yourself, too. But I’d like us to hear some poems. I wonder if you could read “Pillowcase With Praying Mantis.”

Cole: Yes. When she took my canvas bag, the list with the page numbers was in there.

Ó Tuama: I’ve got it here. This is Middle Earth, page 32.

Cole: Which book?

Ó Tuama: Middle Earth.

Cole: Oh, Middle Earth, yes. And which page?

Ó Tuama: 32.

Cole: Maybe I should say too that that revealing part of writing, the autobiographical component, is actually the least interesting part to me.

Ó Tuama: I know.

Cole: The art making impulse of assembling words into sentences and then sentences into stanzas and making similes, all of that is just so much more exciting to me than, the other part is actually kind of embarrassing.

Ó Tuama: You say that so often, Henri, that I’m really drawn to hearing you say more about it, because read you say that in so many interviews.

Cole: Well, I don’t know that there is to say, it is what it is.

Ó Tuama: Well, I’ve got a question for you in a while, so we’ll see.

[laughter]

Cole: Okay. Which page was it again?

Ó Tuama: Thirty-two.

Cole: Thirty-two. I know in my students, if I have a student who wants to reveal more than create language, I kind of trust that talent less…

Ó Tuama: Interesting.

Cole: …than the one who just is kind of in love. Even if the language is so over the top, it’s nuts, that is a good sign, I think. The other impulse I fear sometimes can come from ego, I think that’s why I resist it.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: So this poem is from, it’s said in Japan, in a town just north in the outskirts of Kyoto, where I lived when I was 45. I was born in Japan and this was the first time back. And in this apartment I lived in two tatami mat rooms, and it had a tiny backyard, but the backyard was just full of praying mantises, of all things. So that was really the context. My father had died and my mother was quite sick.

“Pillowcase With Praying Mantis”

“I found a praying mantis on my pillow.

‘What are you praying for?’ I asked. ‘Can you pray

for my father’s soul, grasping after Mother?’

Swaying back and forth, mimicking the color

of my sheets, raising her head like a dragon’s,

she seemed to view me with deep feeling, as if I were

St. Sebastian bound to a Corinthian column

instead of just Henri lying around reading.

I envied her crisp linearity, as she galloped

slow motion onto my chest, but then she started

mimicking me, lifting her arms in an attitude

of a scholar thinking or romantic suffering.

‘Stop!’ I sighed, and she did, flying in a wide arc,

like a tiny god-horse hunting for her throne room.”

Ó Tuama: There’s so many lines in that I love, but that last one, “like a tiny god-horse hunting for her throne room.”

Cole: It’s very fanciful. It is. It’s very fanciful, it’s funny to read it.

Ó Tuama: If you talked like that over lunch, I’d be delighted rather than thinking that you were peculiar.

Cole: It’s very — In Virginia, we would once a year maybe encounter a praying mantis decades ago. But this was extraordinary, they’d be all over the window.

Ó Tuama: You wrote in Orphic Paris, which is a memoir of a year that you spent living in Paris, you wrote, “A poem must burn with a truth-seeking flame and be a small symphony of language.” And what we will see over and over again throughout the poems you’re going to recite, is this small symphony of language. And I’m really curious to hear from you, with the various poems that you read, what is the “truth-seeking flame” in it? As you look at that poem, what is the truth that that poem is looking for?

Cole: Well…

Ó Tuama: Or burning with?

Cole: …it’s human feeling. To me, it’s human feeling. It’s fear, it’s grief, it’s desperation, it’s triumph, it’s wonder. I think every poem has to have human feeling, but it also must have a symphony of language. And I think there’s a lot of poetry around that does one or the other. And it’s okay, but I really, as a reader, want both. I guess it’s an autobiographical component to some extent. That’s the truth seeking flame. Though it doesn’t have to be. It could speak to historical moment. It could speak to something in the world. It could have an ethical component. But it has to have that fear, grief, desperation, triumph, wonder thing, or it doesn’t work for me.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. I wonder, I forgot to mention this one to you, but I wonder if you could read “Homosexuality” from Blackbird & Wolf?

Cole: I could do that.

Ó Tuama: Page 29.

Cole: Okay, thank you.

Ó Tuama: I would’ve made a good librarian. It was my fantasy job as a child.

Cole: What is it?

Ó Tuama: A librarian.

Cole: A librarian?

Ó Tuama: That was my fantasy job as a child, to be a librarian.

Cole: Oh.

Ó Tuama: So there’s something about librarians knowing page numbers, Blackbird & Wolf. See, I was thinking page 29.

Cole: Why are you saying that?

Ó Tuama: I’m just filling in the gaps while you were looking for the book.

Cole: I lost the link, I’m sorry. The —

Ó Tuama: Blackbird & Wolf, page 29.

Cole: Twenty-nine. Okay. So this poem is a one sentence poem. There are two narratives in this poem, one is something that is happening in a bedroom, and the other is in parentheses in the sentence, which describes a kind of journey of coming out, you might say. So one is a metaphor for the other. And it has this title, “Homosexuality.” I think this poem appeared in The New Yorker, which amazes me when I think about it now, that it did.

“First I saw the round bill, like a bud;

then the sooty crested head, with avernal eyes

flickering, distressed, then the peculiar

long neck wrapping and unwrapping itself,

like pity or love, when I removed the stovepipe

cover of the bedroom chimney to free

what was there and a duck crashed into the room

(I am here in this fallen state), hitting her face,

bending her throat back (my love, my inborn

turbid wanting, at large all night), backing away,

gnawing at her own wing linings (the poison of my life,

the beast, the wolf), leaping out the window,

which I held open (now clear, sane, serene),

before climbing back naked into bed with you.”

That’s a sweet poem.

Ó Tuama: It is a sweet poem.

Cole: It’s a sweet poem.

Ó Tuama: I am so struck in the way that you reveal yourself in it, and I can hear in interviews you’ve given, and even now, that you have caution about a poem that’s only autobiographical or only revealing the self. And yet, alongside that caution, you continue to reveal yourself in vulnerable ways. How does that vulnerability sit with you?

Cole: I don’t know. I don’t know, that’s a hard question. “How does it sit with me?” Do you mean in reading the poem or in — I think, I don’t know. I think the danger in writing in middle age is a certain kind of sentimentality, which I think men are more susceptible than women. But somehow I think gay men are less susceptible to it, for reasons we don’t have to go into.

Ó Tuama: Okay. [laughter]

Cole: But I look at it as my metier. That’s part of the profession, is to go as far as you can. You were speaking — he was speaking to me before we started about a mutual friend of ours, a wonderful poet named Marie Howe, and when she was here before — last time I saw her was here probably, five years ago — she said, “I want — ” On stage, she said, “I want you to read the poem that scares you the most. What is the poem that scares you the most?” And I don’t think about it quite that way, but it was a very interesting thing to think about. And there are of course still poems that I can’t write. I’ve actually written a few poems that I only want to be printed after I’m gone, just because they’re, to me they’re so private. And it’s nice that there are private things.

Ó Tuama: And yet there’s the impulse to write them, if only for the audience of yourself. What is that impulse for you?

Cole: I suppose it’s aesthetic. It gives me great pleasure to get it right, to get it down and to get it right. That’s a whole different kind of pleasure than someone responding to it and saying, “That’s a great poem.” Or publishing it in The New Yorker even. That’s all nice, but the excitement of getting it down and being truthful and going as far as you can with interesting language, there’s nothing that comes close to that for me.

Ó Tuama: That’s that symphony of language, if only for the audience of yourself, that I’m hearing.

Cole: Yes.

Ó Tuama: You speak a few languages.

Cole: I don’t speak. I speak one language, but I read French and I speak like a seven-year-old child, maybe in French, which is — a very sensitive, intelligent seven-year-old child.

[laughter]

Cole: But Armenian was also spoken in the house where I grew up. My mother and my grandmother spoke Armenian, it was their first languages. So, my mother was a French woman, born in Marseille and went to French lycée, et cetera, but she raised us as American kids. And I was Henry actually until I finished college. But now for 40 years I’ve been — I was christened Henry, but for 40 years I’ve been Henri.

Ó Tuama: And this love of language you have, do you think that came from a multilingual family where you heard all the languages being spoken? Or was —

Cole: I’m sure there’s a connection to it. I go to France maybe three times a year, four times a year, and I’m sure that’s connected to my mother, a kind of maternal protective thing. But I think if you’re aware — You know, my students at Claremont McKenna, many of them are international students, they speak three languages. And that is an enormous gift to a young poet, to just be aware of three ways of saying “window,” the plainest object, is a marvelous gift.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: It’s not necessary, but it is a gift. English — American books in English are translated into so many more languages than other language books are translated into English. I feel a certain responsibility to other languages as well, in terms of — Also as a reader, I think — I don’t know. If I’m looking at a international anthology of poetry, there are many more models, it seems to me, than you get in an American anthology. There are many subjects and races and genders in an American anthology, but in terms of style, it’s a much narrower pool it seems to me than an international. So I like to look at with my students, I use an international anthology with my students for that reason.

Ó Tuama: I mentioned in the intro about your interest in simile, and I’d like us to talk about simile, because it is a particular style of using language to clash with language, by saying something is like another thing. You’re also saying it’s not so alike that it’s the same, but it’s like enough that I want to put them alongside each other. Here’s another few of your similes. This is from “Human Highway,” in the most recent book: “Happiness unfolded like a strange / psychedelic moth, or the oldest unplayable / instrument made from a warrior’s skull, our happiness a little bone flute.” What the hell? That’s extraordinary. Here’s another one from Blackbird & Wolf: “I sprawl on the carpet like a worm composting, understanding things about which I have no empirical knowledge.” And then here’s the last one I’ll mention: “You are beautiful and ugly at once, like a weed or a human.” What is your interest in simile? You make such powerful use of it, it’s shocking sometimes.

Cole: Well, I think I remember as a young man reading Aristotle’s Poetics, and simile was one of the things, he put it — Simile is really high on my altar to poetry, and that was one of the things I remember him saying, that it was a way of measuring a human’s mind, is the connections that you can make.

One of my teachers at Columbia was Derek Walcott, and he is just a magnificent user of similes. Just to describe the ocean, he uses thousands of similes, and that was something I really studied and noticed and admired. And I don’t know, it’s in my toolbox. If you say it’s “like something,” you don’t have to say what it is, it’s terrible to reveal. [laughter] You see that it’s like a divagation, but a divagation that informs or illuminates or defines in an indirect way. And that’s more interesting than saying it straight…

Ó Tuama: Sure.

Cole: …in my view. Sometimes you have to say it straight, but that’s just at the ball game or something, I think.

Ó Tuama: I’m sure it’s different for every poem, but how do you follow the intuition that leads to a simile like, “You were beautiful and ugly at once, like a weed or a human.” Do you just try to free associate and see what happens? Do you have a methodical way of working through it?

Cole: Yeah, that’s a good question. It’d be great if there was a spray for that.

[laughter]

Ó Tuama: I’m sure there probably is.

Cole: I need a simile, and you just spray yourself.

Ó Tuama: Somebody might suggest something to you afterwards.

Cole: It’s hard, I don’t know what to say. It’s not easy. But that to me is one of the things that — I do that in conversation. I actually, in conversation, I guess it’s going to the gym for similes, because I’m always doing, in daily life, that. And so it’s sort of like exercising that simile muscle.

Ó Tuama: But the one that I quoted in the intro, this is from “Childlessness”: “When you died, mother, / I was alone at last. And then you came back / dismal and greedy like the sea, to reclaim me.” “Dismal and greedy like the sea.” Do some similes hurt you when you’re — ? Or do you follow the language and get pleasure from that? Or a bit of both?

Cole: Maybe some of them are painful. I wrote too many poems about my mother and I don’t do that anymore. I was telling you that I don’t do that with God, too, anymore. So, God and mother are in the freezer, but… [laughter]

Ó Tuama: That’s a line, you need to remember that.

Cole: I just don’t — I’m 66, I have to write about other things.

Ó Tuama: Than God or your mother.

Cole: Yeah. But I have a lot of poems. I’m not ashamed of them, no. That’s a youthful poem you’re quoting from, when I had a spool bed. But it’s a funny thing talking about the pain element or the embarrassment element or the shame element or whatever you want to call it, because there’s also this really exciting aesthetic thing going on, of invention and putting words together and making language into art and that — Well, I’m just repeating myself now. So, if anything, there’s a sort of guilt component that you get so much satisfaction out of something that is difficult and possibly painful. On the other hand, Whitman must have felt that when he was writing about the battlefields, visiting. You know what I mean?

Ó Tuama: Sure. It’s the impulse towards art, isn’t it? That art is something that says, look at what happened and I can make something of it, even though it was unmaking me. That there’s almost a kind of a survival element behind the joy of art, I think, that comes from that.

Cole: Yes, yes. It’s an ironic side of poems that pretend to be virtuous, I think, because you can see that their subject may be virtuous, but the writer is actually enjoying a certain exploitation of the desire being stimulated.

Ó Tuama: Whenever I read a book of poetry, I love reading the acknowledgement section at the back, or the kind of marginalia around it. And in almost, I think there’s a few of your books where this isn’t the case, but in almost all of them that I’ve read, in your acknowledgements and thanks sections, you’ve thanked various residencies for giving you hospitality and solitude. And I’ve been so struck by your gratitude for solitude. And solitude is everywhere throughout your poems. I was wondering if you could read “Kayaking on the Charles” from Blizzard, and then we’ll talk a bit about solitude. It’s page 57.

Cole: The Charles River separates Boston, where I have a home, and Cambridge, where Marie used to live.

“Kayaking on the Charles”

“I don’t really like the ferries that make the water a scary vortex,

or the blurry white sun that blinds me, or the adorable small

families

of distressed ducklings that swim in a panic when a speedboat cuts

through, spewing a miasma into the river, but I love the Longfellow

Bridge’s towers that resemble the silver salt and pepper canisters

on my kitchen table. They belonged to Mother. The Department

of Transportation is restoring the bridge masonry now. Paddling

under

its big arches, I feel weary, as memory floats up, ignited by cigarette

butts thrown down by steelworkers. I want to paddle away, too.

Flies investigate my bare calves, and when I slap them hard

I realize they are so happy. I’m their amusement. Sometimes

memories involve someone I loved. A rope chafes a cleat.

I want my life to be post-pas de deux now. Lord, look at me,

hatless, with naked torso, sixtyish, paddling alone upriver.”

Ó Tuama: Sixty-ish is a delicious word to use in the last part of that poem.

Cole: It should be 70-ish now. [laughter]

Ó Tuama: Could you talk about solitude? Because this is a poem — often in your poem solitude comes with a kind of language that can describe some of the pain of it, but there seems to be a profound contentment in this one. I could be wrong.

Cole: Yes. Well, someone said, who was it? Maybe Marianne Moore? That solitude was a cure for loneliness.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: And I believe that. I was just remembering something another of my teachers said to me long ago, a poet named Mark Strand, and he said that being a poet was like being in a room alone in which next door there was a loud wild party going on, to which you were not invited. [laughter] So, that feeling of being aware of your — I’m not a religious person as you know, though I was raised in the Church. But for me, I feel religious when I’m in nature, so I go as often as possible to the woods. Well, a lot of these poems were written in the Adirondacks. Where there’s solitude and where I’m able to write, and where there are animals to write about. And I’m a swimmer, swimming is a big part of my practice. So I don’t think of solitude as onerous. I think of it as a necessity really. I couldn’t do what I’ve done without it. I so admire people who raised children and write at the same time, I can’t imagine.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. Over the last number of years, solitude has been very much in the news as people had to isolate as a result of the pandemic. What for you was the conversation you were having as somebody who has spoken about solitude and written from a place of solitude for decades, in a way that solitude has become a — It’s not like it wasn’t there, of course, solitude’s always been there, but a public conversation about it.

Cole: Well, I guess I was totally prepared for lockdown. I was. I had a pod of three other people. And one of them cooked dinner for me every week, and she was sort of my mainstay. She’s a person in her 80s. A younger artist who I think was broken down by it all, and then one other poet was in my group. I don’t know, that was an ideal life, actually.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: I was in Boston, I continued to teach electronically, from Boston to California. But, I think it was a time in which poetry was like oxygen or something. It was like a kind of nourishment for us all.

Ó Tuama: Ha. And what did you think of the language being used about solitude in public? You’re so attuned to language and wishing it to be that small symphony. Did you think that the language about solitude and isolation, and did you find it — was there anything interesting? Anything that you thought uplifted the public conversation?

Cole: I don’t know that I thought about that. I know that a lot of people suffered a lot from it, but I’m — I don’t even —

Ó Tuama: Nothing comes to mind?

Cole: Yeah. I didn’t get the virus. You know, I lived through another virus, a virus that there was never a cure for, that killed a whole lot of people. And at that time the government wasn’t at all interested, and now we have a cure and medicines and all these people who don’t want to be vaccinated. So, I feel confused actually by it, bewildered by so much of what has taken place. The way my generation had to fight for medicine in comparison is…

Ó Tuama: And attention, not just medicine, but attention.

Cole: Yeah.

Ó Tuama: A scientist friend of mine, as COVID was breaking out, decided to look up the stats about epidemics, and immediately thought, “Well, the most recent one was the Spanish Flu,” so turned back to that, and then looking through books realized, “Oh my God,” and she was asking herself: Why didn’t it even occur to me to pay attention to the numbers about HIV and AIDS? And she was telling me that, just saying, “As a scientist, what was it that meant that I could gloss over that, when somewhere in the back of my mind the numbers were there?” And she was kind of exposing herself as thinking —

Cole: Yes, it’s because it was gay.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: It was because it wasn’t the dominant culture that was affected mostly. It was not just gay, it was all sorts of African countries, the virus is still teaming, so…

Ó Tuama: Yeah, but a particular projection onto it was, that it was a disease, gay-related immune disease, as it was called initially. Yeah.

Cole: Yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Ó Tuama: I wonder, could you read along this line, could you read, “Gay Bingo at a Pasadena Animal Shelter” from Blizzard?

Cole: Yes. I was thinking maybe —

Ó Tuama: If there’s another one you’d rather?

Cole: Well, I was thinking of that poem, “Keep Me,” was that on your list?

Ó Tuama: It wasn’t, but read it. So I don’t have the page number for you. I can entertain you with another story about my wishing to be a librarian, if you like.

[laughter]

Cole: Librarian.

Ó Tuama: I would’ve been a terrible librarian, I’m far too chatty.

Cole: There are several poems in this book that look back to the 1980s, that’s why I thought of it. But “Gay Bingo” looks back as well, so I don’t know how we’re doing on time. I should say that a lot of these poems that I’m reading are, I don’t know, they’re sort of psychological sonnets, you might say, which is another way of saying that they’re not rhymed and they’re not metered, but they have in them the sort of psychological fractures and leaps and resolutions in them that the sonnet form enables. And this is one of those.

“Keep me”

“I found a necktie on the street, a handmade

silk tie from an Italian designer. Keep me,

it pleaded from the trash. There’s probably

a story it could tell me of calamity days long ago.

Then yesterday, tying a Windsor knot around

my neck, I heard voices, Why have you got

that old tie on? Suddenly, Mason, Roy, Jimmy,

and Miguel were pulling at my arms, like it was

the ’80s again, a darksome decade, with another

hard-right president. My lips were not yet content

with stillness. We were on our way home

from a nightclub, I adore you, Miguel moaned,

but have to return now. Remember

death ends a life, not a relationship.”

Ó Tuama: That’s such an elegy to those names you mentioned.

Cole: Yeah.

Ó Tuama: Why did you want to read that one?

Cole: Just because so directly relates to the —

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: I went to New York in 1980, and my whole coming out really coincided with the AIDS epidemic. It might’ve been part of why I was a late bloomer. But I spent the next 12 years there in New York, and they were the worst years for the AIDS epidemic, of course. But I never wrote about it then. It’s only recently that I’ve been able to. Shall I read the “Gay Bingo” thing?

Ó Tuama: Sure. We can all do with a bit of gay bingo. Page 58.

Cole: This is a California poem. “Gay Bingo at a Pasadena Animal Shelter.” It’s the last poem in this book, Blizzard.

“My bingo cards are empty, because I’m not paying attention.

I can’t hear the numbers, because something inward is being

given substance.

“Then my mother and father appear in the bingo hall and seem

sad and solitary.

They are shades now, with pale skin, and have no shame showing

their genitals.

“This is before I am born and before a little strip of DNA—

mutated in the ‘3os and ‘4os, part chimpanzee—overran the community

“and before the friends of my youth are victims of discrimination.

I resemble my mother and father, but if you look closer,

you will see that I am different, I am Henri.

Don’t pay no mind to the haters, Mother and Father are repeating,

“and I listen poignantly, not hearing the bingo numbers called.

I think maybe my real subject is writing as an act of revenge

against the past:

“The beach was so white; O, how the sun burned;

he loved me as I loved him, but we did what others told us

and kept this hidden. Now, I make my own decisions.

I don’t speak so softly. Tonight, we’re raising money for the

shelter animals.

“The person I call myself—elegant, libidinous, austere—

is older than many buildings here, where time moves too swiftly,

taking the measure of my body, like hot sand or a hand leaving

its mark,

“and the bright sunlight blurs the days into one another.

Still, the sleeping heart awakens,

and, pricked and fed, it grows plump again.”

Ó Tuama: Part of my curiosity about this poem is that line, “I think maybe my real subject is writing as an act of revenge / against the past.” It’s hard for me to read beyond that, when I read that line. I can appreciate the power of it in terms of the language. I’m really curious about the “truth-seeking flame” behind that line.

Cole: Well, in this context of this poem, I think it’s trying to preserve a decade, not to forget it, at this time just of so much death and suffering. I think really that was what that writing it down is an act of revenge against its forgetting, I think is what I intended.

Ó Tuama: Yeah

Cole: It’s not a melancholic poem. What is it? It’s sort of, I think I wanted it to be strong.

Ó Tuama: It’s empowered.

Cole: I wanted the voice to be strong and ardent, though it is, of course, sorrowful.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. Well, “Now, I make my own decisions. / I don’t speak so softly.”

Cole: Right.

Ó Tuama: The voice is declaring itself back to itself.

Cole: It’s great about writing, is that you can write it even if it’s not true.

[laughter]

Ó Tuama: Does it make it true though, when you write something like that?

Cole: I feel a little embarrassed to have written that.

Ó Tuama: Really?

Cole: One of the reasons I became a writer, I think, is because when you write, you have total control. And as a young man growing up in the South, as a discreet, shy person, my brothers were jocks, blah, blah, blah. But when I wrote I was a jock. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: You could be anything.

Cole: You might say, so.

Ó Tuama: And does that change you to write into a voice? Does that give you some other self that speaks back to yourself?

Cole: It’s just satisfying.

Ó Tuama: Just satisfying.

Cole: Yeah. It’s just satisfying to be — in my way I’m fulfilling my voice.

Ó Tuama: You wrote in Orphic Paris that a poem is “organized violence.” You might’ve been quoting somebody when you wrote that.

Cole: Yes, who said that?

Ó Tuama: I have the page number, but I didn’t write down who said it.

Cole: Yeah, I’ve forgotten now. Oh, I think it was my teacher, Richard Howard.

Ó Tuama: Okay.

Cole: Richard Howard.

Ó Tuama: It’s a powerful sentiment, a poem as “organized violence.” And I wondered if you could read, “Dog and Master,” which is in Nothing to Declare.

Cole: I think I was writing about Sylvia Plath when I used that quote.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Cole: Oh, which book was that?

Ó Tuama: Nothing to Declare. Page 57.

Cole: Thank you.

“Dog and Master”

“Consider the ermine—

territorial, noxious, thieving—

its dense fur whitening

when light is reduced.

Mesmerizing its victims

“with a snake dance,

killing with a bite to

the back of the neck.

Born blind, deaf, and toothless,

the male is called a ‘dog,’

“a roamer, a strayer,

a transient. But huddled

in my arms for warmth,

with my fingernails

stroking his underbelly,

“he forgets his untamable

nature. His rounded

hips shiver like mine.

In folklore, he holds the soul

of a dead infant; and in life,

“he prefers to give himself

up when hunted, rather

than soil himself. This is

civilization, I think, roughly

stroking his small ears.

“But then, suddenly,

I’m chasing him around

the dining room screaming,

‘No, I told you, no!’ like two stupidly

loving, stupidly hating

“creatures in a violent

marriage, or some weird

division of myself,

split off and abandoned

in order to live.”

That’s a weird poem.

[laughter]

Ó Tuama: I love it.

Cole: That’s a weird poem.

Ó Tuama: It is weird. “Organized violence.”

Cole: This poem, I didn’t — First off, I should say, please nobody go by an ermine. They’re vicious little creatures and you don’t want one as a pet. I didn’t actually have one as a pet. I saw a painting of a woman in the 19th century and she had her ermine, and I completely projected myself into the life of this — So, this is an instance of my belief that a poem can have emotional truth without being necessarily based on fact. I think that’s certainly very true.

You know what’s funny about creatures? I was just reading Geography III with my students. The last poem in that book is a poem called “Five Floors Up.” It’s not a great Elizabeth Bishop poem, but it’s amidst these very great Elizabeth Bishop poems. But the occasion for that poem is that she hears down below someone with their dog and he’s saying, “Shame on you, shame on you,” to the dog. [laughs] And actually, I just read another poem, which was saying something to a creature. And then yesterday I was buying a coffee at 6:30 in the morning, and the woman was tying up her dog outside, and she was saying to the dog, “Now, you wait here with your little brother.” And the little brother was this other little dog. And it just is curious how, it’s not so artificial, is it? The use of animals as a stand-in for humans.

Ó Tuama: Totally. Yeah.

Cole: But here I’m trying to get at — I do think in all of us, there are two adjacent rivers, and they have very different spirits.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. As is evident in this poem. Chasing each other around the room, screaming. And the dining room too, a place to eat or something else.

Cole: Yes, it’s like yin and yang.

Ó Tuama: You said earlier on that you’re not religious, but you love nature. I’m curious about, for you, when you write a poem like this, that features us looking at nature, looking at this ermine, looking at its wild nature. What is it about that that draws your attention so much? I understand that you’re using the ermine as a metaphor, but you’re also looking at it and paying attention to it and showing it’s “born blind, deaf and toothless.”

Cole: Yes. Yeah. No, I had to study. I get a lot of my ideas from paintings actually, walking around museums and just sort of, poem titles from painting titles. I think I am just trying to get at this idea of, there was this super — Well, an ermine is adorable, but vicious. It tears apart, it’s got long nails, and sharp, sharp teeth, meant to destroy, to tear open your organs. And yet, it was being cuddled by this pearl-draped finery of a woman. And I think whenever I see this confluence of two things like those, it’s a gift to the poet. And I think that’s what I was trying to get at.

Ó Tuama: We’ve got some time for some questions. I think we probably have space for maybe three questions.

Cole: Has this been a little interesting?

[applause]

Ó Tuama: Yeah. A lot interesting. If you’ve got a question, you can come up to one of the mics up the front here, and maybe share your name, and just dive us right into the question.

Cole: This happens like once in seven years in my life, so don’t think this is like a normal conversation. It’s very special to be with someone that has read my poems and that I — When you meet readers, a circle is complete, you might say. All the odds, when you are sitting at a desk and beginning to write something, you’re not thinking about the end of the circle at all. And it seems like all the odds of a capitalistic world are against the possibility of the poem actually finding a reader. So, this is like, I don’t know, a big orgasm or something.

[laughter]

Ó Tuama: Speaking of similes.

Cole: This is really kind of too pleasurable to really even process.

Ó Tuama: You’re in a room of readers of your work, Henri. So, yeah, the pleasure is ours, continuing on that awkward simile. How about we go over here.

Audience Member 1: I’d be happy to take part in that, Pádraig. Henri, you mentioned that some of your work feels like sonnets, but without rhyme and meter. And then you named a number of characteristics that a sonnet has, that these poems have, without the rhyme and meter that is characteristic of a sonnet.

Cole: Yes.

Audience Member 1: Can you talk more about that? What were those things and how did they come out in your work?

Ó Tuama: Well, I mentioned — Let’s see, what do I mention? Fractures and leaps and resolutions. In a sonnet, you have 14 lines; in an English sonnet, you have three quadrants and a couplet; and then a Italian sonnet, you have octave and a sestet. I’m kind of more drawn to the Italian model, which is sort of like a deep breath and then an exhale. But if you look out in the world, there’s models of that eight-six, all over the place. If you think of a tree, for instance, and this foliage of a tree over a trunk, that’s sort of like the Italian sonnet, you might say. And you get the opportunity at the — The sonnet has this thing called a volta, which is a seed of change, a ecstatic, transformational shift. And so, when I’m writing my sonnets, I like for it to have that seed of change. It can’t be a kind of just tell a little story poem, it can’t be linear. There has to be, if you were hiking, it would be like a switchback.

And then the ending is where the real reveal has to be. Which is also a component of the sonnet. I started writing them when I was living in Japan, as I mentioned, I was 45, and I couldn’t figure out what kind of poem to write. And I thought, “Well, I could just be a American tourist and write tankas and haikus,” but no, I’m not going to do that. I thought, well, what if I brought some of the qualities of Japanese poetry to the shortest lyric form in my language? And that’s really how it originated. And then I’ve just written more and more of them, with other longer poems in between. Thank you for your question.

Audience Member 2: I kind of had the same question. But maybe I could just rephrase it a little bit, in terms of why you’ve kept with this form, what it has given to you over time as a poet.

Cole: Well, I’m always trying to think of ways to tweak it. As I say, I think it’s a sort of idyllic form. It’s written in so many languages, it can be political, it can be private. I’m always looking for some way to alternate it. I was going to maybe read “Tomorrow Night,” one with the longest lines. It’s written on a horizontal page rather than a vertical. I’d never really tried to do that, to write, so I thought I’ll write the sonnet with the longest lines in the world. And that’s what I tried to do. But, I don’t know, it could be that I’m in a trough and I’m thrashing around and trying to get out somehow, and I just haven’t figured out a way. But there’s time, there’s time.

It seems like, one of the effects of computer writing I think is prolixity, prolixity, is that a word? Prolixness? Verbosity, the scroll button, and with my students and the narrow screen, it’s just longer and longer and longer and longer and longer poems are being written. And I just thought, well, I’m going to write a poem that could appear on a tiny little telephone screen. So, I’m going to go the opposite direction, I thought. More is not more. I don’t have to say that to you all because you’re experienced, but my students don’t believe that. More is not more, more is less, almost always. Yes. Yes, I didn’t see you, I’m sorry.

Audience Member 3: No, no. A comment and then a question. My wife and I are long time actors, and you said something that I was glad to hear you say about privacy and being private, where it doesn’t matter what a critic would say, it doesn’t matter even what a reader or a witness of a — when we’re doing theater, a witness says, you know yourself when something is so deeply true that you’ve lost track of time and space, and it’s just coming out of you true. So thank you for illuminating that in your process.

Cole: Thank you.

Audience Member 3: But then the question is, and it sort of relates to the other two questions. It seems like more and more I’m reading — and I’m curious from both of you, actually, as teachers — more and more reading more prose, things called prose poetry. And during the last couple of years, my wife and I have taken writing classes online, and I find myself going between what the teacher would say, “Oh, that’s more like a literary essay, even in a short form as opposed to a poem.” And there’s a confusion there as a novice…

Cole: Yes.

Audience Member 3: …as to, is this thing prose poetry? To me, it’s like, is there certain music and simile and rhyme that makes something a poem, or is there a place where we cross over and we go, no, that’s no longer a poem, that’s a very short literary essay or story?

Cole: Yeah, that’s —

Audience Member 3: I’m just curious.

Cole: Well, we live in a time of hybridity. I have this book, he mentioned it, I wrote about Paris, which is written in prose, but it’s written in poetic, you know. And I didn’t know what it was. So I wrote down, “This is a meditative memoir, travel journal, photo album, essay poem.” [laughter] So, I mean, hello?

Audience Member 3: Those [inaudible] cover more ground there.

Cole: So, I don’t generally write prose poems. Louise Glück has some prose poems in her recent books, and she does them as fables. They’re short paragraphs. And as little fables, they’re kind of exquisite, jewel-like objects. My sense of the prose poem comes through sort of more from French literature than American literature, and prose poems are different, they’re not so narrative and linear.

I’m not interested in linearity, as you’ll see from my memoir, but I don’t think there’s a prose poem police. I think there’s — I mean I hope there are no sonnet police, because I would be in jail. [laughter] Anything is possible. I think mostly writers, they don’t want to lie down and be obedient to a form, they want to splash a little of their coffee on it, and leave their scent on it some way. That’s my sense. The writers that are sort of more obedient are kind of less interesting, generally.

Ó Tuama: Thank you for the questions. I actually was going to ask you to finish us off by reading a little bit from Orphic Paris, because I’m so struck by that quote from it where you talk about a poem being a “truth-seeking flame,” as well as then as “a small orchestra of language.” I think I’m misquoting it, but —

Cole: That’s okay.

Ó Tuama: Those two parts to it. And there’s that bit where you describe a man who is sitting next to you, and I feel like it encompasses solitude and profound tenderness as well, because your gaze outward, whether towards an animal or towards yourself or towards other people, is so often very tender, but brutal in the sense of that you’re not feeling like you can help or change, but you are watching with a gaze of tenderness. And I wonder, as a way of praising your — for us to honor your work and for you to leave us with the last word with your work…

Cole: Sure.

Ó Tuama: …if you could read that section on page 116?

Cole: Just to answer what you’re saying. I do think human kindness is our most important — I mean, kindness is our most important quality as humans. It does separate us from, sometimes from the animals, not always. So this is just a paragraph, a long paragraph, in this meditative memoir, travel journal, photo album, essay poem. [laughter]

“Today a man was weeping next to me at the brasserie. He was young and drinking a Coke with a lemon slice bobbing in it. Every few minutes he wiped the tears from his cheeks and looked at me apologetically. He was wearing snug denim pants and his sideburns were neatly trimmed. Had he seen his future in the bar mirror, I wondered? Had his young body, by unfair election, been touched by the incurable virus that has touched so many in my lifetime? Did he need a doctor? I was not at all prepared to encounter him, like a figure from the Old Testament under olive trees, with the scent of rosemary or lavender in the air. He seemed to float somewhere between heaven and earth. Moses, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Noah, and Adam were in the distance, back behind him. In the mirror, the sunshine made strange, flame-like wing patterns. On his table, a little bouquet of colorful posies made flames, too. He seemed super real to me, because there was nothing unreal about him or his sorrow. I wanted to speak to him but was afraid. We were both alone, and waiters hurried past, ignoring us. The young man had moist green eyes, like rough emeralds. Outside, in the square, a big scarred plane tree was shaking its branches. On the horizon, swollen clouds moved quickly. Nearby, on the pavement, a crow pushed its yellow beak into a seeping pink trash bag. I ordered a bowl of wild strawberries, which are in season, and took out my notebook and pen, because I didn’t know what else to do. Why do the gods make a sport of their play with us? We are all born in a womb and end up in a tomb, I wrote down.”

Thank you.

[applause]

Ó Tuama: Henri Cole. Thank you very much for the honor of hearing your words today.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections