Chen Chen

I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party

Has a guest ever been a soothing influence on a complicated family gathering?

In this poem, a son writes to his parents and invites them to a meal, letting them know that his boyfriend will also be there. He gives instruction to his parents on how they should behave, parenting his parents. In all this family tension, the boyfriend’s question “What’s in that recipe again?” offers calm, and builds lines of connection that had otherwise seemed unlikely.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

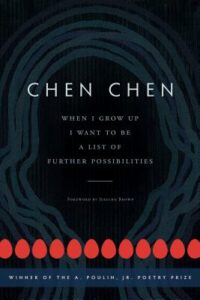

Chen Chen is the author of When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities, which was longlisted for the National Book Award for Poetry and won the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry. He teaches at Brandeis University as the Jacob Ziskind Poet-in-Residence.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and what I love about poetry is that it’s always trying to do a few things at once. Sometimes the person speaking in a poem, the “I,” sometimes that person is really frustrated and annoyed, and the idea is that when I’m reading that poem, I can be brought along and feel like I’m on their side, and I get them, and I wouldn’t make the same mistakes as the people who are annoying them. But always, in those poems, too, there’s the invitation to consider it from the other side and to begin to realize, Oh, maybe I’m the one who’s annoying that poet, and maybe I wouldn’t get it, and that the poem itself is calling me into a new imagination of myself, especially when I face my realities.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: “I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party,” by Chen Chen:

“In the invitation, I tell them for the seventeenth time

(the fourth in writing), that I am gay.

In the invitation, I include a picture of my boyfriend

& write, You’ve met him two times. But this time,

you will ask him things other than can you pass the

whatever. You will ask him

about him. You will enjoy dinner. You will be

enjoyable. Please RSVP.

They RSVP. They come.

They sit at the table & ask my boyfriend

the first of the conversation starters I slip them

upon arrival: How is work going?

I’m like the kid in Home Alone, orchestrating

every movement of a proper family, as if a pair

of scary yet deeply incompetent burglars

is watching from the outside.

My boyfriend responds in his chipper way.

I pass my father a bowl of fish ball soup—So comforting,

isn’t it? My mother smiles her best

Sitting with Her Son’s Boyfriend

Who Is a Boy Smile. I smile my Hurray for Doing

a Little Better Smile.

Everyone eats soup.

Then, my mother turns

to me, whispers in Mandarin, Is he coming with you

for Thanksgiving? My good friend is & she wouldn’t like

this. I’m like the kid in Home Alone, pulling

on the string that makes my cardboard mother

more motherly, except she is

not cardboard, she is

already, exceedingly my mother. Waiting

for my answer.

While my father opens up

a Boston Globe, when the invitation

clearly stated: No security

blankets. I’m like the kid

in Home Alone, except the home

is my apartment, & I’m much older, & not alone,

& not the one who needs

to learn, has to—Remind me

what’s in that recipe again, my boyfriend says

to my mother, as though they have always, easily

talked. As though no one has told him

many times, what a nonlinear slapstick meets

slasher flick meets psychological

pit he is now co-starring in.

Remind me, he says

to our family.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ó Tuama: I first came across Chen Chen when I read his book When I Grow Up, I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities. So I’ve been a fan of Chen Chen’s for a while. So I saw this poem in a magazine and thought that it was quite brilliant. And the setting of the poem just makes it so easy to follow along. It’s like a story unfolding. It’s a great narrative poem. And in it he hides all these brilliant reflections.

So many poems are in conversation with a piece of old mythology. And what I love about what Chen Chen’s doing here is that his poem is in a conversation with Home Alone. And he treats Home Alone as a coming-of-age narrative, as a thing, as a story that people would have turned to in conversation with their lives. And, by so doing, he lifts Home Alone to the level of mythology and formative narratives.

But that’s what every piece of mythology is. It always started off as a story told to kids at night, or a story that was scandalous and filled with sex and death and fights and reconciliations. And so he, in many ways, shows us how movies are the mythologies of today. And he does something brilliant as a poet, in the context of bringing the story of Home Alone into this poem which is so filled with humor, as well as filled with great sadness, I think, and great hope.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Chen Chen uses humor and the humorous stating of bald fact in this poem, to great effect. This poem could be called “My Parents Disappoint Me,” and we would enter into this poem with a much different sensibility, instead of which the poem is just called a very basic thing: “I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party.” And then the way within which they RSVP, they come — there is that very clever, almost Winnie the Pooh-style narration when it says, “My mother smiles her best / Sitting with Her Son’s Boyfriend // Who Is a Boy Smile. I smile my Hurray for Doing / a Little Better Smile.” And in the poem, so many of those titled smiles are in capital letters; they’re capitalized, the first letters of each of those words — “Sitting with Her Son’s Boyfriend Who Is a Boy Smile” — as if there is such a smile. Which there is, clearly: he is letting people know that there is that kind of awkward, forced smile, coming from both him and from her, and the modest ways within which, when people are placed in awkward situations of new learning, that even small progress is progress, and that we might find a way to support each other in small progresses.

That’s the thing: that the poet has modest expectations here; and even those modest expectations, for much of the poem, you realize aren’t progressing along so easily. And that’s sad. It can be difficult, when you have something that’s important to you that you wish other people to acknowledge being important. And when that’s a stumble, when it isn’t fluent, there’s real hope, I think, that there could be fluency, in this poem. And the boyfriend, when the boyfriend comes in, and the boyfriend brings great fluency.

When he comes in as character, Chen Chen says, “My boyfriend responds in his chipper way.” And that could be because he knows everything that’s going on and has decided to say, “Look, I can be chipper here.” It could be that maybe the boyfriend doesn’t quite get everything that’s going on and is just being chipper because he’s not getting why this is so painful to Chen Chen. It’s hard to know which.

And then, toward the end, the boyfriend turns to the mother and says, “Remind me / what’s in that recipe again,” as if that’s just been a longstanding conversation and they’ve had loads of conversations before about these recipes. And I think that the poem resolves itself into something really beautiful — that Chen Chen has been trying to create a situation where his parents will extend something like family to this awkward gathering around a dinner table, and, actually, it’s the boyfriend who does that. And so: “Remind me, he says / to our family” is the last line. And “ours” — the family is created by the boyfriend’s creating of it. Within this mother, father, and son trinity, the boyfriend is the one — in the hospitality of language, the nonchalance, maybe, the understanding or, even, the lack of understanding, there is something being created by the latest addition to the table, rather than the latest addition to the table being the one who’s desperate for approval.

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I think there’s a moment of change in this poem, which moves from the powerful desire that many of us have, to want our parents to accept us, because this poem could’ve been called “I Tried to Make My Parents Accept Me.” And the poem really hinges on “We Create a Space for My Parents” and “we” being himself and the boyfriend. And they include the parents in this, “our” family. And it’s beautiful. And there is a wisdom and a maturity in this poem that has moved beyond the demand for attention and the giving of power to parents, to say, “Your approval will or won’t dictate my responses to what this circumstance is.” And this poem is on that hinge and is moving into that sense of saying, “Well, no, we’re doing it anyway, and you’re welcome to come along.”

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: My parents were really awkward when I was trying to introduce Paul to them. And I had in my mind to say, Let me drop his name on the phone regularly, so much so that, eventually, they’re gonna say, “How is Paul?” And that never happened, and I was just like, how on Earth can we do this if they’re not even gonna say his name? Because I thought, step one is going to be doing that, and step two is going to be doing that, and step three is going to be doing that.

And a friend of mine said, “Why don’t a bunch of us go on down to Cork, and we’ll all meet up?” Because my parents are lovely people, and my friend who suggested this knows my parents; said, “They’re great. And the idea of something can sometimes mean that people feel awkward. Meeting people face-to-face is gonna be totally different.” So we went down, and —there were six of us — went down from Belfast and met up with my parents.

And it was all a bit awkward. And then Paul turned to my dad and said to my dad, “Can you explain Schrödinger’s cat to me?” And my father looked at him with this absolute delight and glee, because if there’s one pathway to my father’s heart, it’s physics. And so Dad and Paul chatted away about Schrödinger’s cat.

And then, a few months later, at one of my sister’s weddings, Paul went and asked my mom out for a waltz, during the dance. And a few months later I was down in Cork, and my mom said to me, “Come here.” And she gave me a packet. And in the packet was a blanket that she’d knit — she’s a great knitter — and then she said, “That’s for Paul. Tell him thanks for the dance.”

And I had had a number of years of trying to initiate what the conversation and the language of acceptance would be. And, in many ways, my attempts for those were limited, because I thought that they would be the way that I would measure progress. And they weren’t. They were in the language of physics and the language of knitting and the language of dancing and the language of gesture and the language of person-to-person. And it’s still awkward, in the sense of that I live in an Ireland — I’m 44, and I’ve grown up during a period of time when people have learnt awkwardness about these things. And so it’s never going to — we’re never going to be able to undo the fact that that’s the Ireland that I grew up in. But it’s changed so much. And I had to learn to observe the language of love as it would work, rather than dictate the language of love as I thought it should be.

[music: “Kid Kodi” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ó Tuama: And I think what we need to recognize, when we’re in moments like this, is that all the languages are necessary: the language of words; the language of gesture; the language of proximity; the language of attempt; the language of failure; and then, where we can, the language of forgiveness when things don’t work out; and the language of repetition. There’s so many languages happening in the context of this poem, and all of them are contributing towards people moving closer towards each other and appreciating the substance of each other’s lives in a way that is beneficial and dignified.

And it can feel painful that we need to school each other in those ways, but I think the imagination that “we” are always going to be the ones who need to school other people in our ways — that’s limited, because, eventually, somebody else is going to be schooling us in the way of understanding their life, and we might feel unfluent and awkward and trying to figure it all out. And somebody else might be frustrated at us that we’re not getting it.

And so there’s an easy way to try to identify with the narrator in this poem, the “I,” Chen Chen in this poem; and I think, especially as a gay man, I find myself immediately identifying with him and thinking, Oh, God, the awkwardness of that and the difficulty of it. I wonder, though, where will be the situation in my life where I will be identified with the parents in this, and I will seem slow to understand and slow to appreciate and awkward, and asking questions that other people might wish I weren’t asking? And how can we navigate what the language of gesture and time and repetition and engagement and trying looks like in that context?

[music: “Every Place We’ve Beenr” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: “I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party,” by Chen Chen:

“In the invitation, I tell them for the seventeenth time

(the fourth in writing), that I am gay.

In the invitation, I include a picture of my boyfriend

& write, You’ve met him two times. But this time,

you will ask him things other than can you pass the

whatever. You will ask him

about him. You will enjoy dinner. You will be

enjoyable. Please RSVP.

They RSVP. They come.

They sit at the table & ask my boyfriend

the first of the conversation starters I slip them

upon arrival: How is work going?

I’m like the kid in Home Alone, orchestrating

every movement of a proper family, as if a pair

of scary yet deeply incompetent burglars

is watching from the outside.

My boyfriend responds in his chipper way.

I pass my father a bowl of fish ball soup—So comforting,

isn’t it? My mother smiles her best

Sitting with Her Son’s Boyfriend

Who Is a Boy Smile. I smile my Hurray for Doing

a Little Better Smile.

Everyone eats soup.

Then, my mother turns

to me, whispers in Mandarin, Is he coming with you

for Thanksgiving? My good friend is & she wouldn’t like

this. I’m like the kid in Home Alone, pulling

on the string that makes my cardboard mother

more motherly, except she is

not cardboard, she is

already, exceedingly my mother. Waiting

for my answer.

While my father opens up

a Boston Globe, when the invitation

clearly stated: No security

blankets. I’m like the kid

in Home Alone, except the home

is my apartment, & I’m much older, & not alone,

& not the one who needs

to learn, has to—Remind me

what’s in that recipe again, my boyfriend says

to my mother, as though they have always, easily

talked. As though no one has told him

many times, what a nonlinear slapstick meets

slasher flick meets psychological

pit he is now co-starring in.

Remind me, he says

to our family.”

Lily Percy: “I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party” by Chen Chen was originally published in Poem-a-Day on April 19, 2018, by the Academy of American Poets. Thank you to Chen Chen for giving us permission to use his poem. You can find a link to the poem in our show notes, along with Pádraig’s guiding question for this episode.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections