David Fox and Bruce Weigl

Sacrifice and Reconciliation

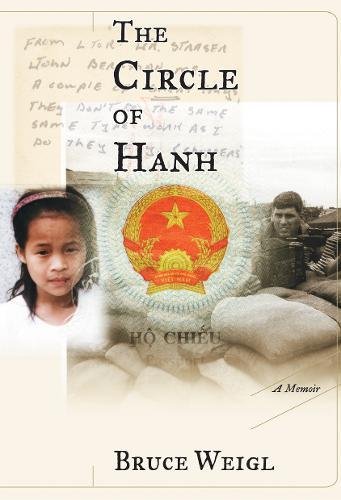

In remembering the legacy of four World War II chaplains — Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish — who went down together with their torpedoed ship in 1943, we speak with David Fox, nephew of one of the chaplains. We also hear interviews with surviving veterans and veterans of the German ship that torpedoed them. Finally, a conversation with author, poet, and Vietnam War veteran Bruce Weigl. His most recent book, The Circle of Hahn, chronicles the long personal journey he has made back to Vietnam and to the adoption of a beloved Vietnamese child. The paradox of his life as a writer, he says, is that the war ruined his life and gave him his voice.

Image by Westend61/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

David Fox

Bruce Weigl is an author, poet, and a Vietnam War veteran.

Transcript

May 27, 2004

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today two stories of war and surprising acts of reconciliation that followed. Bruce Weigl will take us into the terror and the beauty he found in Vietnam. But first, the story of four chaplains and nearly 700 other men who died on the troop ship Dorchester off the coast of Greenland in February 1943, the third largest American loss of life at sea in World War II.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: He eventually got his orders to go overseas and it was a very difficult goodbye, and I looked at him through the windows of the train, and I was crying and he was crying, and I knew I’d never see him again.

MS. TIPPETT: At a time in America when religious identity kept Jews, Catholics and Protestants apart, these four chaplains of different faiths gave away their life jackets, linked arms and went down together praying with the soldiers who could not leave their ship. David Fox is founder and director of the Immortal Chaplains Foundation, and he has interviewed the surviving veterans of the Dorchester.

DAVID FOX: The story of the immortal four chaplains begins with, of course, the four men themselves. And they were unique in that they were all of different faiths and came together on this boat, a US troop ship called the Dorchester. And they were Clark Poling, who was a Dutch Reformed minister from upstate New York; and then there was Rabbi Alexander Goode, who was a rabbi out of Washington, DC; my uncle, who was George Fox — he was a Methodist minister up in Vermont — he actually had three parishes at one time and was called a circuit rider even then; and last was the Catholic priest, Father Washington from New Jersey. And they met on the Dorchester at the end of January 1943, and the — I interviewed the first sergeant of the ship who was on deck at the time when the four of them met. So that was interesting because I actually got to experience what it was like to know what they were like when they got together, and — and he explained that they were immediate friends. They just sort of hit it off together, and they started laughing and joking, and they had a — a bond almost immediately between the four of them. On board, the chaplains began to organize entertainment for the men, and the men would tell me in the interviews I did that they were always together and that was remarkable for them.

MS. TIPPETT: Was that their job?

MR. FOX: Yes, it was their job to — to provide stimulation for the men, things for them to focus on other than knowing that there was a submarine out there, and they soon found out that they were, in fact, being trailed by submarines. So the chaplains kept their spirits up, they organized a talent night and apparently the chaplains were the biggest hit themselves. They were quite talented singers — I think all four of them were. And Rabbi Goode, Alexander Goode, was also the son-in-law of another rabbi, Rabbi Jolson, who was the father of Al Jolson.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. FOX: Yeah. So he had considerable connections to show business, so they became very — very popular on the ship.

[Excerpts from the Audio Archive of David Fox]

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 1: Rabbi Goode, he could sing with the best. He would hold his services as the others hold theirs, and we all went to all of them. We were on a ship. We had nothing that we could go, and so when they had services we went.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 2: Lots of times they were together, they were going around and trying to keep morale up. And they all worked well together; they seemed to fit right in. But I just felt closer to Father Washington. He see — just seemed right at home even in the atmosphere of a troop ship.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 3: There was a couple of fellows playing cards, and Father Washington came wandering through shortly after I got in there. I was watching the game. He came over and he stood behind a fellow. And this fellow turned around to him, he said, `Father, would you bless my hand?’ He looked at it and he said, `I should waste my blessing on a lousy pair of treys?’ I — I thought that — that was just like him.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 4: The captain had just said that there was five — at least five submarines trailing us. They picked them up on radar, you know, and they said if you — they hit you — that’s when they told us, `If they hit you, you don’t have to worry. Two minutes you’ll be dead.’

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 5: So I start making my rounds. I went upstairs. I thought it’d be better to tell our men, `Take off our boots, put on our shoes’ — boots are too heavy, shoes are easy to move — remove. I walked that ship continuously talking to the men.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 6: So it was about 1:00 in the morning, I guess, and there was one — one escort ship was a Coast Guard cutter ahead of us, and two on each side, and the two freighters, then we were in the middle. And it’d only do about nine, 12 knots top speed. And the Dorchester was loosing speed, you know, with the heavy seas. And we dropped back out of the convoy and there we were set right in the open and when we were there — when we were in the open, that’s when they hit us.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 7: And I was sitting in a — in a — in a stateroom right off the — the starboard side I was on. And then we’re sitting there playing cards and — and I went to snap the cards down and instead of saying `Gotcha,’ I raised the card like that, everything went black. I said, `What the here was that?’ I said, `We’re hit.’

MS. TIPPETT: The Dorchester was 90 miles off the coast of Greenland where the water temperature of the Atlantic in winter is roughly 36 degrees. A storm the night before had frozen many of the lifeboats to the railing. Life jackets, each with a small red locator light offered the best, though still slim, chance for survival.

[Excerpt from the Audio Archive of David Fox]

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 8: I just come off guard duty. I took my jacket off, and the next thing you know, boom. And before you know it, the ship was rocking, and who had time to even think about a life jacket at that time?

MS. TIPPETT: Again, David Fox, nephew of Chaplain George Fox.

MR. FOX: The chaplains organized the men. They would hand out these life jackets, put them on, and then they would lead them to a place where they could jump off and not be hurt. The chaplains, without any hesitation, just simply took off their own jackets and placed them on the next man who was waiting there.

[Excerpts from the Audio Archive of David Fox]

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 9: Lights went out and steam pipes broke and the screaming and the very, very strong odor of burnt powder — gun powder. I had to talk to myself. I had to fight off the panic which I heard was going on. I called out on deck and I looked around, there wasn’t a soul on the ship. Not a soul. It’s always best to get as many people to abandon a ship with you, hold on or tie on with anything so there’ll be a group of lights. The Coast Guard sees a group of lights, that’s where they’re going first. But this way looked like a city out there, with the lights. Looked like a large city. And the ship now — by now is floundering and I looked down toward the stern, toward the back of the ship, I see a bunch of heads moving. I was so happy that I got somebody to go abandon ship with. I must have lit up like a hundred-watt lightbulb. I went down there. Good Lord, there’s 10 men, not a word is said, not a word. All the men and the chaplains opened up with prayer and I see that they were not going overboard. They were not going to abandon ship. They were going to hold our last service. I began to say my prayers — say my prayers, you know, and shed tears. I couldn’t abandon ship there. I went back to the port side, two feet to jump. As I jumped, the ship broke. A huge wave pulled me away from the ship. Another wave hit me, and I got a mouthful of oil. It was choking me and I — and I heard a voice. `Pull him up.’ There was a lifeboat there. `Pull him in.’

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 10: There was — oh, we must have had about 20 guys in the raft. I remember they piled one on top of the other, you know. And by the time they picked us up I think we had six or seven left. You know, they got cold and froze, they just slid off. There’s one guy hanging on the back of the raft. I held him up for — I don’t know how long it was. Time don’t mean nothing, you know. And finally, he was dead. I — I had to let him go.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 11: We seen bodies all around drifting, and as I say, the chill of the water got most of them and they were just drifting around. You seen those little lights a-bobbing up and down, and there was no life in the men that was in them, either.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 12: We could look back and some flames and a fire had broken out, and there was enough reflection of that in the water to be able to see the ship.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 13: There were soldiers hanging on to the rail of the ship. We had little red lights on our life preservers. As I turned around, I saw a sight that will forever be with me. It was the Dorchester making its last lurch into the water. And it looked like a Christmas tree.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 14: When she rolled, she rolled to starboard, and all I could see was the keel up there, and there we saw the four chaplains standing arm-in-arm on the top of the boat, and then the — the boat took a nosedive and went right down and they went with it.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 15: They never even made a move. They just joined hands and the four of them — was two Protestant and a Hebrew chaplain and a Catholic chaplain. I asked Father Washington, `Father, get off the ship. The ship’s going down.’ `No, no,’ he says, `Go ahead. You get off. Get off,’ Because the ship was starting to list, but they made no attempt to get off at all. They just went down.

MR. FOX: Those who saw that — and not everyone saw it, but those who saw it said they had never seen a finer — one man said, `I never hoped to see anything finer between here and heaven.’

READER: Dear Mr. Fox, I’m writing a letter to you in remembrance to the event for nearly 55 years, which led us together, and also the last living sailors of the German submarine U-223. During the war, everybody served and even died for his country — your soldiers on the Dorchester who could not be rescued as well as our sailors who were defeated and drowned by the depth charges of your destroyers. The four chaplains are genuine heroes, and their sacrifices has to be preserved for future generations. We have to learn out of the past for the future so that our children and grandchildren and further generations to come can live in peace. Never again should happen such a murderous war. Yours sincerely, Kapuska.

MR. FOX: I had to go to Germany and interview the survivors of the U-boat to put the pieces together.

MS. TIPPETT: Again, David Fox, who directs the Immortal Chaplains Foundation.

MR. FOX: There were about six of them still alive, though I was able to interview three of them, including the first officer of the submarine, who’s the last surviving officer. And also the chief munitions (German spoken) — he handled the torpedoes, he actually had his hand on the torpedo that sank the Dorchester — and interviewed him. And that was so moving to go to Germany and say, `Hello. You’ve never met me, but you killed my uncle 55 years ago,’ or whatever it was.

MS. TIPPETT: How did he…

MR. FOX: That story…

MS. TIPPETT: How did he respond to meeting you?

MR. FOX: They were cautious at first, but when I said I’m — you know, `I’m coming not to blame you, but to me that — there are two sides of the story.’

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I think that must have been astonishing for these German veterans because they did lose the war and they are held responsible — the German people in general are held responsible for such horrendous crimes. They’re not often offered forgiveness.

MR. FOX: That’s right, and I felt that just as the chaplains reached out to each other, I said I felt that as a representative of the families of the chaplains I wanted to reach out to them because I — I felt that the chaplains would have forgiven them, and therefore my going said that.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, with a program to commemorate Memorial Day. My guest David Fox has shared the informal interviews he conducted with the surviving veterans of the troop ship Dorchester on which nearly 700 American soldiers died off the coast of Greenland in 1943. David Fox has also made contact with the veterans of the German submarine that torpedoed them, and they, like the American soldiers who witnessed the event, have been profoundly affected by the legacy of four chaplains of different faiths who linked arms and went down together with their ship. In 1997 David Fox created the Immortal Chaplains Foundation in Minnesota. The foundation awards an international prize for humanity to recognize acts of faith and reconciliation which counterbalance more familiar images in our world of violence.

MR. FOX: The first prize was given posthumously to a man on board one of those Coast Guard cutters, the Comanche, and his name was Charles W. David, and he was a black man and he was a big man. He was from New York City. And when that ship, the Dorchester, went down, he went over the side of the Comanche and pulled up white men in 36 degrees temperature water, sometimes, they said, two at a time. And Charles W. David died of exposure, of pneumonia, because he did that.

MS. TIPPETT: After saving all those lives.

MR. FOX: After saving those lives. dink Swanson, who was his comrade on board, came and accepted the award in his place. He was his shipmate. dink was white, Charles was black. And…

MS. TIPPETT: And, again, we’re talking 1943.

MR. FOX: 1943.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. FOX: And when that ship went into the port in St. John’s, Newfoundland, they couldn’t go to the same place together. They couldn’t go into the same club, they couldn’t go in — do things together. They were segregated. And yet he did that with his life. So that was the first prize. And then the second one was to a young girl, you know, an American girl from California, Amy Biehl, who went to South Africa and was stoned to death. She went there to fight apartheid, and ironically was bringing a black friend back to their home in the Soweto neighborhoods, and she was stoned to death by a group of black people. And her mother and father came from California to accept that award, and it was Archbishop Desmond Tutu who presented the award. And that meant a great deal to him.

MS. TIPPETT: I remember that story clearly.

MR. FOX: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: It was so stunning that they also went and testified at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, right? And…

MR. FOX: Exactly. And asked that the — the killers of Amy be forgiven.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm. You — you also, I believe, arranged for some of the German sub veterans to meet — did they meet the veterans…

MR. FOX: Quite.

MS. TIPPETT: …of the Dorchester?

MR. FOX: Yes. When Rosalie, the rabbi’s daughter, and I — we started to share how important it would be to keep the story alive, but also to tell the story of others who have done this. So I contacted Archbishop Desmond Tutu in South Africa and I asked him if he would be a part of this. And it was such a great thing for him to come here and participate in our first event in Minneapolis.

[Audio Clip]

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: Some of us might preach eloquent sermons about laying down one’s life. They lived out their sermons. Isn’t that a wonderful sentence, that? They lived out their sermons by dying. Jesus said, `Unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains barren. It remains alone. If it dies, it brings forth abundantly.’ Have we not here in the saga of these four wonderful men an extraordinary illustration of both of these sayings? They should have disappeared from the face of the Earth as they did physically, as they went down into the icy cold waters of the Atlantic. But isn’t it extraordinary that now the opposite has happened, that instead of oblivion and forgetfulness, they receive glory and honor. For greater love than this has no one, that a person should lay down their life for their friends.

MS. TIPPETT: Archbishop Desmond Tutu preaching at the first awards ceremony of the Immortal Chaplains prize for humanity in Minneapolis in 1998. The following year, the prize recipients included Paul Rusesabagina, a Rwandan hotel manager who sheltered 1,000 people of the Tutsi tribe while 800,000 others were slaughtered by his own Hutu tribesmen. David Fox counts as one of his great memories an unsolicited visit he received after that award from a later prime minister of Rwanda. It turned out that he was one of the people Paul Rusesabagina kept alive in his hotel.

MR. FOX: This is something that is beyond my anticipation…

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. FOX: …my expectations. I had no idea that we would touch people in this way.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, you know, there’s — there’s something in this story about — about ripple effects…

MR. FOX: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: …and about the larger unseen possibilities in a moment, and it doesn’t — it doesn’t take the tragedy away, but there was so much reconciliation and — and compassion and goodness that was possible to come out of that over time. And it’s true of every other story you’ve told me, all of your other recipients of the award.

MR. FOX: Right. Right. And I have to mention one other thing, too. I was scheduled to go and talk to a school — a hi — a hi — a high school on a — a day in April that was the day after the Columbine, Colorado, massacre. I got a letter from the — from the principal the next week, and he said, `After you spoke to the students on that day,’ he said, `the following assembly, students started to get up and publicly apologize to people that they had pushed out and made to feel less than themselves.’ And he said it was that — the combination of that story of the — what the chaplains did and the catharsis of — of Columbine, the recognition of not having compassion, excluding people, pushing people apart. He said, `That story that you told has an amazing power to it.’ So that’s why we feel it’s important to keep this alive.

[Excerpt from the Audio Archive of David Fox]

UNIDENTIFIED MAN 16: I think that that simple act — simple but it was great — has changed my life. I — I try to do more for people. I don’t worry about me so much. I’m — I’m doing something for somebody else.

MS. TIPPETT: A veteran of the troop ship Dorchester from the audio archives of David Fox. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break we’ll return with Vietnam veteran and poet Bruce Weigl. His writing enlarges comprehension of the Vietnam War and the possibilities of the human spirit. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, a special program on sacrifice and reconciliation to commemorate Memorial Day. My next guest, Bruce Weigl, went to Vietnam as a soldier in 1968, one of the two and a half million Americans who served there from the early 1960s until the Paris Peace Agreement of 1973. Over 58,000 American soldiers were killed in Vietnam, and over 300,000 wounded. Today, Bruce Weigl is a poet. His book The Circle of Hahn chronicles the long personal journey he’s made back to Vietnam and to the adoption of a beloved Vietnamese child. The paradox of his life as a writer, he says, is that the war ruined his life and gave him his voice.

BRUCE WEIGL: First, it was adventurous, but then quickly that turned into something very different after I saw the first injured people that I — that I was forced to confront. I think the first person I saw seriously injured was a Vietnamese farmer who had stepped on an American landmine, and he happened to be in a field hospital at Camp Evans, where I was stationed for my base camp. And half of his body was gone, yet he was still alive and screaming. I’ll never forget his face and I’ll never forget those screams. And then suddenly one minute I was one person, and after experiencing just that first incident, I was another person. And I suddenly began to realize that I had no idea what I was in for and — and where I was and what I was doing.

MS. TIPPETT: There is also this remarkable source of a gift really and a salvation in your story in that you have this occasion to begin to read.

MR. WEIGL: Yes. I guess it turns out to be my good fortune to have gotten a really bad case of dysentery and got sent back to a larger base camp at a place called Ankai. And I was laying in a — on a cot recovering, and a Red Cross volunteer came through the tent where I was with other sick soldiers and he had a box of paperback books. And he was just tossing them to people, saying, `Here, read this.’ And he tossed one to me, and I really didn’t have that much interest, although I started reading. I couldn’t pronounce the names in the book, yet there was a quality to the voice that was telling the story that — that…

MS. TIPPETT: And the book was?

MR. WEIGL: Crime and Punishment — Dostoevsky’s great novel Crime and Punishment. I think not a bad first book for a writer to read.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if that newfound dream was one thing that sustained you in that time even before you yourself did begin to write.

MR. WEIGL: I — yeah, I think it did, the sense that I had this desire to want to somehow record what I was seeing around me was something that sustained me. And just the love of — the love of words that I was already beginning to feel.

MS. TIPPETT: It seems to me there are some — some words that you use a great deal and they become very evocative. And one of those words is `enormity.’ What do you think of or what stories do you think of when you say that word?

MR. WEIGL: I think I think of divinity, however you want to call that — God, powers greater than myself, the enormity of the historical forces that were at work. You know, I could never at that time as an 18- or a 19-year-old have articulated any of this. But, you know, I was like a sponge. Ignorance served me well. I was too stupid to realize that I couldn’t do what I had in mind that I wanted to do. But I must have had some kind of vague sense that I was witness to the great machine of history right before me.

MS. TIPPETT: When you were in Vietnam, did you have a sense of divinity, even an ironic one?

MR. WEIGL: Well, yeah, I was raised a Catholic and I — I always loved church as a kid. I always felt great peace and salvation and grace when I went to Mass, and great peace when I went to confession and Communion. And then when I was in the war, I actually witnessed a priest in preparation for our assault at Khe Sanh in 1968, which was one of the largest — supposed to be one of the largest battles of the war, blessing a cache of — of armaments. And I immediately said, `This is wrong. This is not — you know, the God that I grew up loving, the Jesus that I grew up loving wouldn’t do this, wouldn’t bless these things that are going to be sent out to murder human beings any minute.’ So I let go of my ties to the church, and — although I never let go of my belief in that which we call divinity, you know, the officialdom of the church in that context. It was heartbreaking almost for me. I think I got lost for a long time without the church because I don’t think I realized how important it had been to me until I was without it.

MS. TIPPETT: Many of the qualities that seem to be part of the relationship that you eventually had with Vietnam seem to me to be sacred religious qualities of compassion…

MR. WEIGL: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: …reconciliation.

MR. WEIGL: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: I’d like to know — I’d like to hear about how you ended up — having had this experience, which was devastating in many ways — how you’ve come to see Vietnam now as the home of your heart and — and you have so many connections with the place.

MR. WEIGL: Yeah. Yeah, great. I’m going to have to go back just a little bit further…

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WEIGL: …because I have to say that when I was there, I really loved the Vietnamese people that I had contact with. And I thought, in spite of all the bad stuff that was happening around me that it was an absolutely breathtakingly beautiful place. I liked the food, I liked the people, I liked the landscape. These are things that one would not admit to one’s comrades in that context. It would have been absurd. They would have thought I was crazy or that something was wrong with me if I would have shared any of this. And I always had a sense that I wanted to go back. And then lo and behold 20-odd years later, I was invited by the offices of a retired North Vietnamese general in Hanoi in the early ’80s. Not many Americans had gone back to Vietnam. I think we were the — maybe the second group. I agreed to go on this trip thinking that it would never happen. You know, there was still an embargo and — and travel was literally impossible. And suddenly the trip came through and I found myself in Bangkok picking up a visa and an hour and a half later landing in Noi Bai Airport in Hanoi, Vietnam. We were received, I have to say, with such absolutely kindness and generosity of spirit that I was suspicious. I just couldn’t believe after what we had done to those people in that country that we would be received this way. And I thought, `Something is up here. What do they want?’ Fortunately that first trip I got very close to that general and to a few other friends — Vietnamese friends that I made and I got to see that, in fact, there was nothing dubious about their attitude. Their attitude was that we had been in a war together, we had been soldiers on the opposite side. Now that was over. And I began to learn over the years upon my many trips back that, in fact, the Vietnamese love a great deal about our country. Ho Chi Minh had a copy of our Constitution on his table when the war was on.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. WEIGL: Yeah. They love our — our independence of spirit. They love our sense of humor, our openness. They’re very much like us in many ways. And — and…

MS. TIPPETT: Didn’t you also go at some point with other veterans who had become writers?

MR. WEIGL: Yeah. In 1990, we had a remarkable conference with half a dozen or so American writers who had been soldiers in the war, including a few journalists. And we met with 50 Vietnamese writers who had also fought in the war on the side of the — on the side of the North Vietnamese Army. And some were popular resistance soldiers. You know, we would start comparing notes about where we were and when we were there. And it — it wasn’t unusual for some of us to find men on the other side that we had literally fought against, that, you know, we could have killed each other on that day and it didn’t happen. And, you know, just the thought of that was enough to make me pause.

MS. TIPPETT: In those meetings then, I mean, were you able to forgive each other and — and also to forgive yourselves?

MR. WEIGL: Yeah. I — I think that — that, you know, their forgiveness was so — was so overwhelming that it was almost enough for everyone to go around. But in terms of forgiving myself, I think that it has a lot to do with — with the kind of command that you were associated with. I was with the 1st Air Cav., which had an absolutely great command. And there was no nonsense in my outfit. There was no — no abuse of civilians. As a matter of fact, we had very, very little contact with people when we were out in the field. So I think that I can say I don’t feel like I did anything that I’m ashamed of as a soldier. It was more — it wasn’t that kind of forgiveness. It was more, I think, a forgiveness of just having bore witness to that, that there’s a way in which once you cross certain lines about killing and seeing killing and being so close to it that it’s hard then to be among the company of people who haven’t been in that situation. And I think that’s where the forgiveness part came in, that — that — you know, that I felt for a long time unworthy of — of the love of those around me just because of what I had seen.

MS. TIPPETT: Poet and Vietnam veteran Bruce Weigl.

MR. WEIGL: This is a poem of my own called “Song of Napalm,” which is dedicated to my wife. (Reading) “After the storm, after the rain stopped pounding, we stood in the doorway watching horses walk off lazily across the pasture’s hill. We stared through the black screen, our vision altered by the distance, so I thought I saw a mist kicked up around their hooves when they faded like cutout horses away from us. The grass was never more blue and that light more scarlet. Beyond the pasture, trees scraped their voices into the wind, branches crisscrossed the sky like barbed wire. But you said, `They were only branches. OK.’ The storm stopped pounding. I’m trying to say this straight. For once I was sane enough to pause and breathe outside my wild plans, and after the hard rain I turned my back on the old curses. I believed they swung finally away from me. But still the branches are wire and thunder is the pounding mortar. Still I close my eyes and see the girl running from her village, napalm stuck to her dress like jelly, her hands reaching for the no one who waits in waves of heat before her. So I can keep on living, so I can stay here beside you, I try to imagine she runs down the road and wings beat inside her until she rises above the stinking jungle and her pain eases, and your pain and mine. But the lie swings back again. The lie works only as long as it takes to speak, and the girl runs only as far as the napalm allows until her burning tendons and crackling muscles draw her up into that final position burning bodies so perfectly assume. Nothing can change that. She is burned behind my eyes, and not your good love, and not the rain-swept air, and not the jungle green pasture unfolding before us can deny it. “

MS. TIPPETT: The title poem in Bruce Weigl’s 1988 collection Song of Napalm. Six years later, in 1994, Bruce Weigl edited another poetry collection which he himself translated. This collection is called Captured Documents, and it contains informal poems found in the diaries of captured or fallen North Vietnamese soldiers. They are predominantly love poems or verses of longing for family and home. I asked Bruce Weigl to read me his personal favorite, “One Moonlit Night.”

MR. WEIGL: (Reading) Tonight the wind is cold on bamboo trees, the moon hides behind the mountain’s top. In sadness the river ripples. I received your letter and read it nervously through the night, and afterward I knew you grieved for me like a mother and wept. Nephews and nieces wait far away; sorrowfully, aunts and uncles wait, too. You begged me to come home, my love, to the family of our village because my life is still full of sweet promise. You do not understand the way of the truth. Life must be spent for the people’s good. I picked a violet to tuck into my book. Tears mixed with the violet’s ink to weave into my writing. All the wishes I send so you will understand.

MS. TIPPETT: A reading from “Captured Documents,” Bruce Weigl’s translation of poems found in the diaries of North Vietnamese soldiers. Weigl first became a reader and a writer while a soldier in Vietnam. He says that experience both ruined his life and gave him is voice. He’s talking to me about the many ways in which he’s made peace with Vietnam, a country which today he calls “the home of his heart.” As a teacher of college students, he also works to reconcile the mixture of honor and horror that characterizes the human experience of war.

MR. WEIGL: You know, I’ve began to talk to my students years ago about the fact that years ago, you know, all cultures like to look at these things as — as anomalies. And, you know, my question to them was: When are we going to stop saying it’s unusual? We’ve always done it to each other. It’s always been present from…

MS. TIPPETT: Well not only — yeah. And there — but there’s also a — a way in which we are fascinated by it. And there are ways that — that people speak about it.There seems to be a beauty or an ob — obsession that can come with the experience of war.

MR. WEIGL: Absolutely. You know, Robert Stone talks about the beauty of the mushroom cloud, you know, which is an absolutely horrifying image if you think about all of its implications. But, you know, th — I think that it has to do with the absolute bare essential that you’re stripped down to in that kind of context. I — I have a poem in which I say, `Say it clearly and you make it beautiful no matter what.’ There’s a way in which language can make the most horrible thing imaginable beautiful, not because it celebrates that horror but because through the language I think the human spirit transcends that horror; that I think to write the poem, to write the story, to write the novel, the memoir or whatever about that horrible thing is in a way to defeat it, you know, or to take back your life from it.

MS. TIPPETT: R — right. Is it true that you have become Buddhist?

MR. WEIGL: Yes, I have. I had met some monks in Vietnam at…

MS. TIPPETT: While you were there as a soldier?

MR. WEIGL: Once when I was there as a soldier, yeah. I had a remarkable experience with some monks. And then…

MS. TIPPETT: Well, tell me about that. That’s too intriguing.

MR. WEIGL: I guess the terrible and embarrassing irony is I was with a couple of other GIs and we were actually looking for women of ill repute. We can say that on the radio.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, we can.

MR. WEIGL: Prostitutes. And I was led through this maze of rooms and alleyways, and somehow I got separated from my friends. And I — I ended up in this room and there were two or three monks sitting on the floor chanting. And I didn’t know what to do so I just sat down kind of with them. And they looked at me as if I belonged there somehow, you know. There was this, you know, 18-year-old GI stumbling around, and I always felt as if they had instilled something in me.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. WEIGL: Yeah. And I left that room thinking that somehow that this was going to mean something to my life. And then when I went back in ’86 and ’89 and ’90 I met some other monks who I got to spend more time with. They were the friends of writer friends of mine. And I began to then come back and study Buddhism more and more and to practice meditation. And it really began to change my life in dramatic ways. Western medical science says, `Well, you’ve got to put that behind you,’ whereas Buddhism says, `It’s part of who you are now, make a life from that.’ I’ve always felt the sense of being called to something, even as a child, and this sense that there were passageways to other ways of living, other ways of looking at the world. There were portals that led to other ways of understanding. You know, that was a door that opened, that door called Vietnam. And once I became a writer and — and I could re-open that door, which was an easy thing to do, I had 20 years of nightmares — then there’s a way in which there was no turning back, no going back from what I knew was behind that door.

MS. TIPPETT: You mean in terms of the possibilities of — of living with that and — and making sense of it?

MR. WEIGL: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: Uh-huh.

MR. WEIGL: Yeah, just the possibility of living with it.

MS. TIPPETT: Or just living.

MR. WEIGL: Mm.

MS. TIPPETT: So you, at some point, walked through this portal back to that place…

MR. WEIGL: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: …and to the fullness of that place. And you have ended up adopting a Vietnamese girl…

MR. WEIGL: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …when she was eight years old.

MR. WEIGL: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: When did that idea take shape in your mind and — and how did that happen?

MR. WEIGL: We began talking about another child, and then discovered that we couldn’t have another child. And I had been going to Vietnam regularly by this point, and I had visited some orphanages. So I — I broached this idea with my wife and she was up for trying it. It was a long, arduous, complicated process. So — and against the advice of the adoption agency, I contacted some of my friends in Vietnam, and a month later we basically got a call from the adoption agency saying, `You have to go now. They have someone for you.’ I rushed home from my teaching job and there was a social worker there who had a dossier about this little girl whose name was Nguyen Thi Hahn, who was eight years old. And she had a picture, and she said she was going to leave the dossier for us to think about. And I said that wouldn’t be necessary, that we wanted her.

MS. TIPPETT: Just from the picture?

MR. WEIGL: From the picture and from — I think from something inside of us as well, something inside of me that just felt right, the little bit that I read about her. And once I saw that face, there was no saying no.

[Miss Nguyen Thi Hanh reads a Vietnamese Love Poem]

MS. TIPPETT: Bruce Weigl’s daughter Hahn reading a love poem in her native Vietnamese. Bruce Weigl’s latest book is a memoir of his journey to the adoption of Hahn. This is how his book The Circle of Hahn ends.

MR. WEIGL: (Reading) We were all swept up then into a long frantic afternoon of meetings and ceremonies at several different provincial and district offices. More than once along the way a small snag would develop because our timing was off according to one official or another. The snag would always be followed by much animated talk and by the sound of voices rising almost too high in their insistence. I didn’t worry over it. I was on auto pilot. I was most alive but I don’t remember many of the details. I signed a hundred documents, shook hands and thanked the cool officials. And near what I knew was the end of the official drama, I gave my speech in Vietnam. We finally all piled out of the last jury office and drove a short distance into the village to a small open-air restaurant where four long tables had been pushed together and were already being covered with dishes of food and bottles of beer that two or three young women were carrying out from the kitchen. I wanted to sit next to Hahn, to use the occasion of the lunch to speak with her, but I could tell that she was still very shy of me. I knew that Hahn was not accustomed to eating this way. The meal, paid for by Holt, was very special. Hahn stared wide-eyed at the dishes of every food that she had probably ever eaten or seen and some she had probably never seen piling up on the table. And after some initial hesitation and at the urging of Vun, who knew the value of eating as much as you could when the opportunity presented itself, Hahn began to eat. I had never seen a child eat that way before. I smiled to myself as I watched her. I could not imagine where in that small body all of that food was going or how it could be contained there. She ate until the last plate of scraps was taken from the table. I watched her lean back into her chair, bend and stretch her back and then belch so loudly she made herself laugh. Vun scolded her but could not resist laughing as well.

The rest happened too quickly I think for everyone. We drove the few kilometers back to the orphanage where I collected a small bundle of Hahn’s clothes and the album of photographs of her friends and her teachers at the orphanage. I said goodbye to Vun and promised I would try to care for Hahn as well as she had and that Hahn would be my daughter as if she had been born into our family. I turned to watch as alone or in pairs all of the children made their way to where Hahn stood next to Vun and said their sweet and quiet goodbyes. I looked hard at Hahn’s face and I could see some panic in her eyes as our driver started the engine and turned the air conditioner on for our drive back to Hanoi. An impromptu group photograph of the children and staff of the orphanage standing around me in the courtyard was set up but interrupted by a sudden heavy rain. Vun put her arm around Hahn and then I saw that for the first time they were both crying. I wanted to tell Hahn that I loved her, because I did. I wanted to tell her that I wished she would come and be part of our family more than anything else in the world, but that if she wanted to stay in Bingluk and not come home with me, I would understand and I would love her just as much. I almost made those words come out of my mouth but I had the sense for once to stay quiet. Vun let go of Hahn then, and then, looking up into the sky, she pushed her gently toward the van. As we pulled away through the courtyard and the arched gate, I watched Hahn look back more than once. Many children were waving in the rain, their small hands open, their small hands through the distance like lotus blossoms opening on the fish pond.

MS. TIPPETT: From Bruce Weigl’s memoir, The Circle of Hahn. He’s also published several books of poetry, including “Song of Napalm” and “The Unraveling Strangeness.” His volume of informal poetry by North Vietnamese soldiers is “Captured Documents.” Earlier in this hour you heard a conversation with David Fox, the founder and director of the Immortal Chaplains Foundation in Minnesota.

We’d love to hear your reactions to the stories and ideas in this program. Please write to us through our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. There you’ll find background, links and materials for further reading. You can listen to this program again, as well as our previous programs. And while you’re at speakingoffaith.org, please sign up for our new weekly e-mail newsletter. It contains reflections on each week’s program, book recommendations and transcript excerpts. You can also write to us at [email protected], or you can call Minnesota Public Radio at 1 (800) 228-7123.

[Credits]

I’m Krista Tippett. Please join us again next week.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections