How the Dung Beetle Finds Its Way Home

Eugenia Leigh

In a poem about how a small moment can help you make a wise decision, Eugenia Leigh finds the strength to go back home after storming out. No self-pity in the poem, just humor and brilliance. She had every reason to leave, and finds every reason to return.

We’re pleased to offer Eugenia Leigh’s poem, and invite you to read Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen back to all our episodes.

Image by Annisa Hale/ Film processed by Moody's Film Lab, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

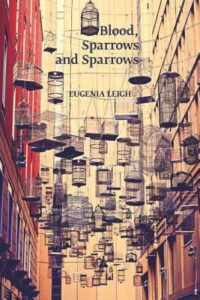

Eugenia Leigh is a Korean American poet and the author of two collections of poetry, Bianca (Four Way Books, 2023) and Blood, Sparrows and Sparrows (2014), winner of the Late Night Library's 2015 Debut-litzer Prize in Poetry, as well as a finalist for both the National Poetry Series and the Yale Series of Younger Poets. She currently serves as a poetry editor at The Adroit Journal and as the Valentines Editor at Honey Literary, a BIPOC-focused literary journal and literary arts organization.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and when I was about 16, I had an argument with my dad. I can’t remember what it was about, but I think it was about my deep desire to become a Protestant because I was convinced that Protestantism was the way forward and he was telling me that I didn’t know what I was talking about. Anyway, I stormed out and I went for a walk. We lived in the country. Along the way, something occurred to me, which was to say I can walk for hours now, and I often did, or I could just go home and see if something new could be said. I came home. He must’ve been expecting me to be away for hours as I normally was. And when I came in the door, he was surprised, and he said to me, “You stormed out like an American.” And he used a metaphor, “stormed,” in the verb there, and then a simile, “like an American,” and I said, “Sorry.” And he was shocked by the sorry. And it didn’t entirely change the dynamic, I was still 16; I was still overly dramatic. But certainly, it faced me with myself. And there was something about me turning around that helped me think maybe I could do something different here.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“How the Dung Beetle Finds Its Way Home” by Eugenia Leigh

“The Milky Way’s glinting ribbon helps the dung beetle

roll his good ball of shit back to the ones he loves.

But blind him to the sky with as little as a hat,

and he will swerve like a drunk who, if he makes it home alive,

“might find the family, soured with waiting,

gone. Drawers cleared, beds cold, even the watercolor ark

of giraffes and raptors pulled from the face of the fridge.

See? I want to tell my missing father, it’s a metaphor so simple

“it’s almost not worth writing down: even beetles need the stars

to nudge them back to where they need to be

when they need to be there—toward their little ones’

gummy grins ever pardoning the grisliest parent.

“I am thirty-four with a son the day my mother tells me

she enrolled in a four-day seminar about how to be a good mom.

A little late, I know.

Once, in a rage, I left my husband and our sleeping child.

“Where did you go, friends ask when I tell the story.

I wish I’d had a grander plan. I wish I’d stood on the roof

of our building and, empowered by that single Brooklyn star,

I’d ripped up the book of my parents’ sins.

“Or I wish I could tell someone the truth: that I fear

I am the kind of woman who could leave the one good family

God had the gall to give her. Really,

I sat on the stairwell leading up to the roof and wept

“until a large bug threatened my life, at which point I recalled

the dung beetles, stopped blaming my parents, and—

thanking the metaphorical stars—I rolled up my pile of shit

and trudged back home.”

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

So much of the question of this poem is, “What’s it about?” And it’s about a dung beetle, of course. It’s about the Milky Way and the fact that dung beetles do actually use the Milky Way to navigate their way as they’re rolling their balls of shit around the place, but it is also about finding a way home. And who? Should a father have found his way home? Should a mother have found her way to being a better mother before the daughter was thirty-four? Or is it about herself finding her way back home after she’s left and has gone up to the roof, not even making it quite as far as the roof? Or is the way home that this poem presents finding a way to not be driven by blame, justifiable blame? I don’t think at any point in this book is the question asked as to whether she is justified or not in having to carry the burden of the things that she’d lived through.

But the question still is: what is her relationship with blame going to be? That’s the wisdom of this poem, is to say: in this moment, that she thought, I’m not going to give power to certain things that happened before to interrupt “the one good family / that God had the gall to give her,” as she says it in such humorous way, in such a painful way too because to say, “the one good family” is a reckoning with a truth that isn’t funny at all.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Eugenia Leigh is a poet, and a writer, and a mother, and a partner as well. And she’s reckoning with the long impact of childhood abuse and the way that now, as an adult living with post-traumatic stress and bipolar, she is trying to think about how poetry can be a vehicle within which she can say something about what it’s like to be the age she is now as an artist, as a parent, as a partner.

The book is titled Bianca, and “Bianca” is a name that was given to Eugenia Leigh’s manic ego when she was younger. It was a way of addressing it and reckoning with the truth of the state that she could find herself in and speaking personally to this part of herself. She is really clear in the acknowledgment section of the book that her writing in this volume is a way of acknowledging ongoing trauma and mental illness. And she quotes the statistic from the National Institute of Mental Health that says, “Pre-pandemic one in five Americans were living with mental illness.” The acknowledgment section of the book finishes with this, “This book is also for you who have known what it’s like to hate your own brain. I hope we learn to love our brains soon.”

[music: “The Gerimo” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Lots of poems — and not just sonnets — make use of a volta, a turn, some point when something’s happening and there’s an interruption, you suddenly begin to see things. And toward the end of this poem, she’s on the stairwell having left the husband and sleeping child, and she says, “I sat on the stairwell leading up to the roof and wept // until a large bug threatened my life.” I love the humor of that and the way that it brings the dung beetle back in. And also, it shows what language can do, how we can laugh at ourselves, and how separating yourself from the moment, finding a way to look at your fear from a different point of view, can sometimes help bring you back to yourself. We’re all in need of a volta, a turn — not just in a poem, but also sometimes perhaps in our life to bring us back to ourselves.

As a result of this poem, I spent far more time Googling “dung beetle” than I ever thought I would in my adult life, or in any part of my life, actually, at whatever age.

It is true that some dung beetles do use the light of the Milky Way to guide themselves when they are on their way back to their habitation. I love how it is that Eugenia Leigh speaks about the adult dung beetle coming back to the “gummy grins” of the little ones, “pardoning the grisliest parent.”

And I suppose part of the question at the heart of this poem is: what is her Milky Way? What will guide her back to the forgiveness of herself, the forgiveness that she can offer a grislie parent, perhaps forgiveness that she wants, too? Maybe she’s calling herself a grislie parent. I don’t know. This poem circles around and tunnels under and plows and questions and queries what it’s like to think about forgiveness, or being free, or released, or letting go. Any of these words might do. None of them are sufficient, but they’re all pointing towards something that is saying that the weight of the past — the serious weight of the past — might only be one thing that’s influencing your life today, rather than the only thing.

Alongside the question about what it might be like to be somehow released or freer from the burden of these things in the past is a question and an exploration as to whether she’s capable of change, capable of interrupting a cycle that might be seen to be repeating itself in her. And what we see at the end is that she does roll up her shit and go home, just like the dung beetle. She transforms the idea of living in your own excrement and living in the shit of the experiences that you’ve been given, she transforms that into something generative and into something that is about return. And that, I think, is where the humor and the hope of this poem meet each other.

[music: “Idle Ways” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The word “metaphor” and the device of metaphor is used throughout this poem: the Milky Way being guided, the dung beetle and its employment, the way within which sitting on the stairwell, not even making it out to see the stars and hiding from the light that might’ve guided her back. There’s so many ways within which she’s aware of metaphor; she’s almost disparaging about it and self-conscious. “See? I want to tell my missing father, it’s a metaphor, so simple // it’s almost not worth writing [it] down: even beetles need the stars / to nudge them back.” And then toward the end, those metaphorical stars, they’re thanked, “thanking the metaphorical stars—I rolled up my pile of shit / and trudged back home.” “Trudged,” a delicious verb to be used here.

There’s a French psychoanalyst who says that metaphor defies what language always veils. And to employ a metaphor, to speak about stars and to speak about shit, to employ this metaphor that says that I need these to hold me together to remind me about what it’s like in the space between a beetle and the sky, to remind me what it’s like to find a way home to “the one good family / [that] God had the gall to give her.” Eugenia Leigh is defying what language veils, which is that family can be difficult, which is that it can be difficult to know how to be yourself, which is that you can find yourself under immense pressure and repeating the very things you always said you’d never repeat.

And what she needs is metaphor that faces you with humor, but also with revealing truth-telling. Despite the fact that you have good reason to wail and despair and to leave, this metaphor is saying there’s also good reason to find your way away from the self-punishing habits and patterns of blame

The friends and the husband and the child are gathered together in a constellation of chosen family and benevolence. That is a beautiful way within which the metaphor of the Milky Way is being represented through these people, all of whom can help her guide herself back home.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

“How the Dung Beetle Finds Its Way Home” by Eugenia Leigh

“The Milky Way’s glinting ribbon helps the dung beetle

roll his good ball of shit back to the ones he loves.

But blind him to the sky with as little as a hat,

and he will swerve like a drunk who, if he makes it home alive,

“might find the family, soured with waiting,

gone. Drawers cleared, beds cold, even the watercolor ark

of giraffes and raptors pulled from the face of the fridge.

See? I want to tell my missing father, it’s a metaphor so simple

“it’s almost not worth writing down: even beetles need the stars

to nudge them back to where they need to be

when they need to be there—toward their little ones’

gummy grins ever pardoning the grisliest parent.

“I am thirty-four with a son the day my mother tells me

she enrolled in a four-day seminar about how to be a good mom.

A little late, I know.

Once, in a rage, I left my husband and our sleeping child.

“Where did you go, friends ask when I tell the story.

I wish I’d had a grander plan. I wish I’d stood on the roof

of our building and, empowered by that single Brooklyn star,

I’d ripped up the book of my parents’ sins.

“Or I wish I could tell someone the truth: that I fear

I am the kind of woman who could leave the one good family

God had the gall to give her. Really,

I sat on the stairwell leading up to the roof and wept

“until a large bug threatened my life, at which point I recalled

the dung beetles, stopped blaming my parents, and—

thanking the metaphorical stars—I rolled up my pile of shit

and trudged back home.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “How the Dung Beetle Finds Its Way Home” comes from Eugenia Leigh’s book Bianca. Thank you to Four Way Books who gave us permission to use Eugenia’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Amy Chatelaine, Kayla Edwards, Annisa Hale, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s book, Poetry Unbound: Fifty Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections