José Olivarez

No Time to Wait

In a church there are liturgies and prayers and statues. But in José Olivarez’s poem, there are more urgent things taking place, things that have “no time to wait.”

We’re pleased to offer José Olivarez’s poem, and invite you to connect with Poetry Unbound throughout this season.

Image by Annisa Hale, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

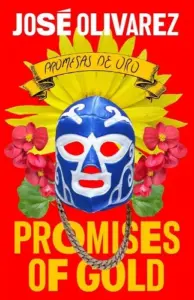

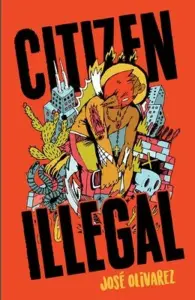

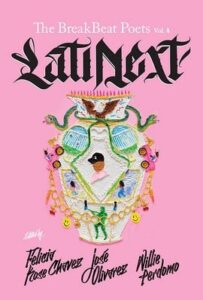

José Olivarez is the son of Mexican immigrants. He is the author of Promises of Gold, a collection of poems. His debut book of poems, Citizen Illegal, was a finalist for the PEN/Jean Stein Award and a winner of the 2018 Chicago Review of Books Poetry Prize. It was named a top book of 2018 by The Adroit Journal, NPR, and the New York Public Library. Along with Felicia Chavez and Willie Perdomo, he co-edited the poetry anthology, The BreakBeat Poets Vol. 4: LatiNEXT. He is the co-host of the poetry podcast, The Poetry Gods. In 2018, he was awarded the first annual Author and Artist in Justice Award from the Phillips Brooks House Association and named a Debut Poet of 2018 by Poets & Writers. In 2019, he was awarded a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. His work has been featured in The New York Times, The Paris Review, and elsewhere.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and for a long time — in all my life, really — I’ve had association with the church, the Catholic Church. And it’s a place of prayer, of course, a place of sacrament, a place of liturgy and community. But whenever I go into Catholic churches, I look around, I look at the Stations of the Cross, I look at all kinds of things, but I also look at the church notice board. Somebody’s saying, “Do you need help with this? Anybody want to come to this group? Anybody want to join here? Anybody wondering what to do in the middle of their week?” That the church notice board is a way that the community is saying, “Look, while we’re in the midst of these huge questions about religion and God and meaning, also there’s stuff that we can offer for help here.” Things you can get and things you can give.

“No Time to Wait” by José Olivarez

“kneeling in the pews, my parents prayed

to the statue of Christ for protection.

“we were new to Chicago. we were new

to the United States. alone you might think,

“but it wasn’t just Christ in that church.

there was the Mexican family that housed us.

“the Mexican family that connected us

with immigration lawyers. the Mexican family

“that got my dad a job. the Mexican family

that invited us to birthday parties. the Mexican family

“that showed us how to make calls back to México.

there was the Mexican family gossiping behind

“our backs. alone? my parents couldn’t drink a beer

without someone’s primo asking for a sip.

“kneeling in that church, there was salvation everywhere.

give Christ the credit if you want, but he never did

“whisper the winning lottery numbers in our ears.

in that church there was a priest offering salvation later

“& there were Mexicans with no time to wait.”

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

So this poem is set in a church with the poet’s parents praying to the statue of Christ for protection. And Christ is mentioned at the beginning and then toward the end as well: “give Christ the credit if you want, but he never did // whisper the winning lottery numbers in our ears.” And so, the idea really is in a certain sense when someone’s praying for something to someone who may not be there, you’re praying to the source of your religion and the direction of your devotion. All kinds of other things are happening, too. And this poem turns away from the idea of prayer being directed to God, prayer being directed outwards, and looks at prayer’s answers coming from the people all around.

The opening image of the poem makes it seem like they’re kneeling in the pews, and that there might be something of aloneness in that. You know, they’re new to Chicago, new to the United States. “alone you might think.” And I love that “you might think” there, because the poem is saying there’s other things happening as well as the one thing that’s being narrated.

And the other thing that’s happening is over and over again, all the others that are there — it wasn’t just Christ in that church: the family that housed them, the family that connected them with lawyers, the family that got the dad a job, the family that invited them to birthday parties, and showed them how to make “calls back to México.” And “Mexico” is repeated over and over and over again in this. This isn’t just families that do that; it’s Mexican families that do that.

So the “alone you might think,” asks you to pause and to go: Really? Is that true? It asks you to choose to do a double-take. What else is true in the presence of an experience of aloneness and experience of newness upon newness? New to Chicago, new to the U.S., and perhaps also looking for protection. You look for protection when you might feel like you are somehow vulnerable or exposed. And it’s asking you to do a double-take on that, too. Exposed, you might think. But actually no, you’re surrounded with all of this support from other Mexican families in the community.

[music: “Kallaloe” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Rather than just making the imagination of this close community to seem like, “Oh my God, that’s absolutely perfect.” It’s also “the Mexican family gossiping behind” your backs. And so it’s saying that this community came with all the hustle and bustle that community always comes with: the absolute delight, the absolute support, the way within which communities can be gossipy, and also the way within which it can be a bit overwhelming.

“alone? my parents couldn’t drink a beer / without someone’s primo asking for a sip.” Someone’s cousin. There’s just this sense of people who are related to each other, people who know what’s going on, and people who are so connected to each other in a way to say, can I have a sip? They’re asking things from each other and so it wasn’t long before they too, were the ones that were giving the help to somebody in the form of giving someone a sip of their beer.

So, I find myself at the beginning of the poem thinking it’s not like they’re the one new family and there’s these other families that have been there for 30 years. There’s probably all kinds of people who have just arrived. They got a bit of help themself. And then they’re also offering help too. That help is being offered and help is also being asked. We’re speaking about, in a certain sense, the sacrament of people supporting people.

And I also wonder, is he saying something of the essence of what religion should be is being found in this sense of connection? That if there is a God, that the God is being found in the space between people, in the offerings they’re making, in the offerings they’re saying: here’s how to give help and also then here’s how to share back.

[music: “A Little Powder” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The language in this poem is filled with clarity, with description. You can see what’s happening right in front of you. This poem is spoken in such plain language that the cleverness of choice kind of is almost hidden. There’s such dextrous rhyme in it: prayed, United States, pews, statue, gossiping, sip, credit, alone, primo, give, whisper, winning. There’s that lovely quiet assonance of the I, — the ih, ih, ih — between give, whisper, and winning. And then in six lines, Mexican is mentioned five times and Mexico once. It repeats and repeats and repeats and is forming a community within itself, a community of sounds that are rhyming with each other, picking up vowel sounds and even repeating words, like Mexican, over and over. And that I think is one of the intelligences of the form of this poem is that it is using not perfect rhyme, but slightly off-the-center rhyme, to speak about how community can be slightly off the center of what a parish is set up for. Here you find a parish that’s doing the work of praying and going to sacrament, et cetera. But it’s also doing the work of supporting people.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

The poem mentions salvation twice. The second time it says, “there was a priest offering salvation later // & there were Mexicans with no time to wait.” So in that usage of the word salvation, it’s kind of saying, “Look, no, we need help with housing and home and jobs and community and places for our kids to go,” et cetera. But earlier on it says “kneeling in that church, there was salvation everywhere.” And so there’s this sense of, you know, the way you think about salvation being for the future, being for glory, being as distant as winning the lottery, that’s one imagination of salvation. But the other imagination of salvation is what’s right here, right now. If you want to say, God, working in the people around you, in the kindness, in the support, in the gossip, in the asking for a sip of your beer, in the giving and getting, and in the welcoming, that that is the salvation that was everywhere in the moment. You didn’t need to wait for it because it knew the urgency and it said: here it is.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

“No Time to Wait” by José Olivarez

“kneeling in the pews, my parents prayed

to the statue of Christ for protection.

“we were new to Chicago. we were new

to the United States. alone you might think,

“but it wasn’t just Christ in that church.

there was the Mexican family that housed us.

“the Mexican family that connected us

with immigration lawyers. the Mexican family

“that got my dad a job. the Mexican family

that invited us to birthday parties. the Mexican family

“that showed us how to make calls back to México.

there was the Mexican family gossiping behind

“our backs. alone? my parents couldn’t drink a beer

without someone’s primo asking for a sip.

“kneeling in that church, there was salvation everywhere.

give Christ the credit if you want, but he never did

“whisper the winning lottery numbers in our ears.

in that church there was a priest offering salvation later

“& there were Mexicans with no time to wait.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “No Time to Wait” comes from José Olivarez’s book PROMISES OF GOLD. Thank you to Corsair and Henry Hold and Company who gave us permission to use José’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Amy Chatelaine, Kayla Edwards, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s new book, Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections