Lorna Goodison

Reporting Back to Queen Isabella

In Lorna Goodison’s imagined scene, Spain’s Queen Isabella receives the ‘report’ of the discovery of Xamaica from Christopher Columbus, an Italian man who was financed by the Spanish court to ransack foreign lands. Lorna Goodison is the former Poet Laureate of Jamaica, and in this tight, terse poem, she’s the explorer: exploring practices of colonization, finance, power and administration. With pomp and ceremony she describes a scene that was as vacuous as it was dangerous.

Letterpress art by Myrna Keliher.

Image by Lucero Torres.

Guest

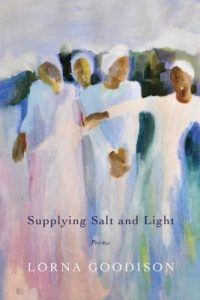

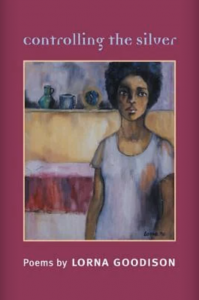

Lorna Goodison is one of the Caribbean's most distinguished contemporary poets. Her work appears in the Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces and her many honors include the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, Americas Region. She is the author of numerous books of poetry, including Supplying Salt and Light, Controlling the Silver, Traveling Mercies, and many more. Her work, translated into many languages, is widely published and anthologized.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the things I love about poetry is reading poetry from different parts of the world. So often, the so-called canon highlights poets, often male poets, from just one part of the world or just a few. But I wanted to read poems about the world that were written from the point of view of the people who lived through them, not just the people who were from the countries that colonized.

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Reporting Back to Queen Isabella” by Lorna Goodison:

“When Don Cristobal returned to a hero’s welcome,

his caravels corked with treasures of the New World,

he presented his findings; told of his great adventures

to Queen Isabella, whose speech set the gold standard

for her nation’s language. When he came to Xamaica

he described it so: ‘The fairest isle that eyes ever beheld.’

Then he balled up a big sheet of parchment, unclenched,

and let it fall off a flat surface before it landed at her feet.

There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.”

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

So for 2019 I decided I was going to read everything that Lorna Goodison has written. And she’s written a lot, so I spent an inordinate amount of time in the words of Lorna Goodison over 2019, and loved her work over years. She’s a painter, and her imagery comes into her poetry so strongly. And then, toward the end of 2019, I got invited to do a profile of her for Image Journal and was thrilled to do so. And of everything that I read, this is the poem I kept on coming back to — for its artistry, for its audacity, and for the profound control she has that leads you towards those last four words — “there were some people.”

[music: “Taoudella” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So this poem is filled with drama and pantomime and pageantry. And one of the things that that drama and pantomime and pageantry does is to hide maliciousness and murder and war-making underneath it. In choosing to say “Don Cristobal” instead of Christopher Columbus, one of the things that you do is you’re brought into a certain Spanish sensibility. And by “Spanish,” I don’t mean by language, I mean, by Spain. And you feel like you’re hearing and seeing everything that’s happening, and you get the impression that you’re hearing the words and the name that people are giving to Christopher Columbus, which is obviously an English usage of that name. You feel like you’re in the Spanish court, hearing that Don Cristobal is gonna come and make a presentation.

Christopher Columbus landed in Jamaica in 1494, and the land was inhabited. The island was inhabited by the Taino, the Indigenous people of the Caribbean and Florida. And the name Xamaica, which was spelled with an X not a J, is an Indigenous, Taino word, meaning “land of wood and water,” and I’ve also seen it translated as “great spirit of land of man.”

So Don Cristobal has returned to his Spanish patron with a report about what he has so-called “found,” and he’s come back as a hero, with treasures of the so-called “New World.” And this phrase, “the New World,” you hear it in so many reference books, or you hear people speak of it, or in maybe historical dramas that are set around the time, and maybe even the way that people now speak about the past, also.

Those terms are so laden with war that they need to be constructed — “found” and “New World,” as well as “hero.” And so whoever invented the term “New World” was a master of spin, because that New World, so-called, wasn’t new. It was older than other places, probably, and it was sophisticated and had government and population and land and trade laws.

But naming it “New” gave license to European people to conduct war but not call it war, to enact murder and enslavement but not call it so, and to corral people into European systems of belief and governance and trade at the expense of the local and established and sophisticated systems of belief and government and trade — and, as well, to conquer language in all of that.

To kill the language of a people is to kill the soul of a people, is an implication that we have in Irish. And I think you see that in so many places, all around the world, that for a conquering people to go in and introduce new gods, introduce new systems, and introduce new languages so the people that they are making war against have to learn a new language to engage in any kind of negotiations back — those are the old mechanisms of colonization. And there’s nothing cute about it. There’s nothing of the New Age of Exploration about it. It was war-making. And it won its wars by murder.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

So there’s a lot of drama in this poem right from the word go. But this drama moves into a very visual way, where Don Cristobal balls up a big parchment and puts it on a table, and it seems to roll over and fall at the feet of the queen. It’s like he’s playing with something, almost reenacting the idea of the edge of a flat Earth. Or he’s putting something at the feet of the queen and paying homage to her and putting it underneath her, as if it already belongs to her, or to walk on. And so at the feet of her now is this parchment with this map of Jamaica.

And there’s this line that Lorna Goodison says: “There we were.” And the introduction of the word “we” is so important here — such a small word, and yet, it is the beginning of an introduction of a people who are being narrated through the stories of empire. And then this list emerges: “massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive / plains, deep valleys, one he’d christened for the Queen / […] wood, over one hundred / rivers” and “food, and fat pastures for […] horses, men, and cattle.” And this list seems to be a long list of all the observations about how this place could sustain Spanish imperial life, as resources were taken away from people who were already in a holy relationship with the resources that were there.

The lush descriptions aren’t just about describing beauty, though. They are describing something that has been looked on with greed and with the assumption of ownership or of taking over or of appropriation or of sustaining large armies that would come, not for geographical curiosity, but for stealing. Lorna Goodison has done a brilliant thing in the shaping of this long list before those extraordinary last words in the final line.

So the word “massif,” which is at the beginning of this long list, is a really intriguing word, because massif is a word that people in Jamaica, and in many parts of the African diaspora, use to speak of a group of people. And so the list seemingly comes across like it’s a list of geographical observations — “massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive / plains” valleys, wood, rivers, food, and pastures. But, actually, what Lorna Goodison has done is to insert a word here that undoes the politics of that and introduces the idea that they knew there were people there first, and over and against the appropriating gaze of the colonizers.

[music: “KeoKeo” by Blue Dot Sessions]

There’s something so important for me, in being Irish, in knowing that the contemporary politics of Ireland is utterly shaped by the history of the last 300, 400, 500, 600 years of British presence in Ireland. And I am always sustained by people from other parts of the world who know that you can’t speak about politics today without knowing the long ache and wound and desecration that colonization brings — and colonization doesn’t end when the colonizing country decides to leave. Colonization continues.

There’s a theory in conflict resolution that conflicts take as long to deescalate as they took to escalate. And I think anybody from a colonized or previously colonized country knows this, and knows that just because whoever they were have gone, that doesn’t mean that things have returned to the way that things should be or could’ve been. You are going to live with the impact of this for a very, very long time, possibly forever.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Reporting Back to Queen Isabella” by Lorna Goodison:

“When Don Cristobal returned to a hero’s welcome,

his caravels corked with treasures of the New World,

he presented his findings; told of his great adventures

to Queen Isabella, whose speech set the gold standard

for her nation’s language. When he came to Xamaica

he described it so: ‘The fairest isle that eyes ever beheld.’

Then he balled up a big sheet of parchment, unclenched,

and let it fall off a flat surface before it landed at her feet.

There we were, massifs, high mountain ranges, expansive

plains, deep valleys, one he’d christened for the Queen

of Spain. Overabundance of wood, over one hundred

rivers, food, and fat pastures for Spanish horses, men,

and cattle; and yes, your majesty, there were some people.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Reporting Back to Queen Isabella” comes from Lorna Goodison’s book Supplying Salt and Light. Thank you to Carcanet Press and McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House, who gave us permission to use Lorna’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections