Mosab Abu Toha

Poems as Teachers | Episode 4

In Mosab Abu Toha’s “Ibrahim Abu Lughod and brother in Yaffa,” two barefoot siblings on a beach sketch out a map of their former home in the sand and argue about what went where. Their longing for return to a place of hospitality, family, memory, friends, and even strangers is alive and tender to the touch.

This is the fourth episode of “Poems as Teachers,” a special seven-part miniseries on conflict and the human condition.

We’re pleased to offer Mosab Abu Toha’s poem, and invite you to read Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen back to all our episodes.

Guest

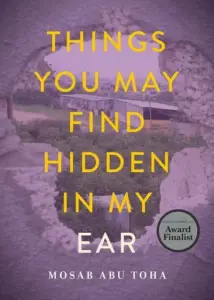

Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian poet, scholar, and librarian who was born in Gaza and has spent his life there. He is the founder of the Edward Said Library, Gaza’s first English-language library. Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear is his debut book of poems: it won an American Book Award and a 2022 Palestine Book Award, and was named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry as well as the 2022 Walcott Poetry Prize. His writings from Gaza have appeared in The Nation and Literary Hub, and his poems have been published in Poetry, The Nation, the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, Poetry Daily, and the New York Review of Books, among others.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and today’s poem is by the Gazan-Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha. Mosab is a brilliant poet and I follow him on social media and read the things that The New Yorker or The New York Times or other publications publish from him. One of his sons was born in the United States, so he and his family were able to escape from Gaza to safety in Egypt, which must be a crisis to be there but hearing from family members who are starving. It’s impossible to read this poem today — the death toll in Gaza is close to 33,000 today — it’s impossible to hear about that slaughter and terror and to read this poem without paying attention to that.

I hold my inadequacy when I read this poem, and all I feel like I can do is to amplify poets like Mosab Abu Toha, to listen to people on the ground, to lament at the geopolitical structures that have these interests in the area that make it so difficult and are so divisive when it comes to splitting huge populations of people such that it feels like the world is saying, This is impossible to contain. Somehow, what we see in the poem is that there is a yearning to say, Look at what might be possible to contain in the imagination, in language, in art; not as an easy solution, but as a painful solution, that will demand exhausting attention.

[music: “The Edge of All There Is” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Ibrahim Abu Lughod and Brother in Yaffa” by Mosab Abu Toha

“The two walk toward the beach,

barefoot.

“With his soft

index finger,

Ibrahim starts to draw

a map

of what

used to be

their home.

“‘No, Ibrahim, the kitchen

is a little farther to the north.

Oh, don’t step over there,

Dad was sleeping there on the couch.’

“Tourist kids run by,

flying kites.

The waves hit

the beach,

shaded with cloud cover.

“The mosque on the hilltop

calls for

prayer.

“Ibrahim and his brother

still argue about where their kitchen was.

They both sit on the sand. Ibrahim

takes out a lighter, wishes he could make tea in their kitchen

for everyone on the beach.

Ibrahim looks upward to what used to be their kitchen window.

The mint no longer grows.”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

So the setting of this poem is of a character, Ibrahim Abu Lughod, and his brother, in Yaffa, on the beach. And the setting is lighthearted. They’re barefoot. We hear about the “soft / index finger” drawing a map in the sand. And there’s “tourist kids” and there’s “waves” and there’s “kites.” And at the same time as this seeming gentle setting — beautiful, you want to be there, you can almost hear the sounds — there is the deep sense that there’s also a past that remains present, that there’s a ghost house there, something that used to be there. And so we have this conflation of the past and the present occurring, all held in a conversation between these two brothers, Ibrahim Abu Lughod and his brother.

Mosab Abu Toha, the poet, published this book in the year 2022; that was the year that he turned 30. So it’s entirely likely that what he’s doing in writing this poem is conjuring up a ghost. Ibrahim Abu Lughod was born in 1929 in Yaffa, and that was then called British Mandate Palestine. He and his family fled Yaffa in 1948 as the state of Israel was being established; initially to Lebanon and then to the United States. He became one of the most influential political commentators on Palestine. And he did return with an American passport to his homeland later on in life. In fact, after he died in 2001, he is buried in Yaffa.

And so it isn’t just the house that’s gone, it’s also this elder statesman, too, that Mosab Abu Toha is calling back from the past and saying; on the beach where there is beauty, on the beach, where there is access to the sea, on the beach, where there is frivolity and the possibility of hospitality and home, that here there are ghosts that have memories of the way things were. And by calling up these ghosts, Mosab Abu Toha is saying something really important about how it is that the past is measured.

[music: “Creatures of Myth” by Gautam Srikishan]

It seems to me that one of the things that Mosab Abu Toha is doing is taking various phrases that are often used to denigrate Palestinians in headlines and conjugating verbs with those phrases, but turning them around almost as a confrontation to say, this is how I wish to use those verbs to speak of ourselves. So “Ibrahim starts to draw.” “A map” is what’s put in the poem, but there’s a line break after “draw,” you can think of drawing a weapon. Then, later on, “oh, don’t step over there.” The idea of where it is that you can go being monitored or policed or somehow there being some danger in where you step. “The mosque on the hilltop / calls for,” there’s a line break and “prayer” comes right after that. But I think what he’s doing is reframing, reasserting. All of these verbs are verbs that are his own language to say, This is how I wish to define who we are as Palestinians, and this is how I wish to define how these verbs should be used to speak about us.

“They both sit on the sand. Ibrahim / takes out a lighter.” And it’s a long line in the poem here. Mosab Abu Toha says that Ibrahim “wishes he could make tea in their kitchen / for everyone on the beach.” Hospitality and being the host put together. So all of these small terms that are put across in mild, light ways in a poem that’s set on a beach with wind and waves and the sounds of kids happening and people drawing in the sand, and, importantly, feeling free enough and safe enough to walk to the beach — all of these things are taking verbs that are often used to denigrate Palestinians in the way that they’re spoken about and reframing them, reasserting them. So often in conflict resolution, what you are looking for is how is it that we can reframe the way within which we’re spoken of and how is it that I can use language where the person about whom I’m speaking would recognize themselves in the language that I use about them?

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

I think there’s an immediate sense that the primary conflict that’s occurring in this poem is that of Ibrahim Abu Lughod and his brother trying to remember where exactly the kitchen was. They’re still arguing by the end of the poem. But partly, I think, that the deepest conflict in this poem is about the measurement of time. Conflicts add up as you look at them. The way that a conflict started can often change and change and change. There’s a Belfast-based writer, Claire Mitchell, who says that there’s conflict about what the conflict’s about, and that can have a way of really obfuscating the question as to where do you begin? And then powers can come in where somebody might say, Well, we’ll never get to the end of that, let’s just talk about what happened yesterday. That, too, is a statement of conflict because the past really does matter. It’s difficult to play the long game when time itself feels like it’s been eradicated, when the home is gone, when the mint is gone, when the possibility of being able to walk to the beach is gone. And so when the ground beneath you has changed, I think this poem is filled with a lament for time and a lament for how time itself has been taken away.

And so it isn’t only that I see these two brothers and the memories of them or the images of them; it seems to be that the crisis of time is what is being put across here.

Sometimes when I’ve done conflict resolution with groups, I’ve said to them, What’s your measurement of time about what we’re talking about? Somebody might say, oh, well, we’re talking about what happened last week. And typically somebody on the other side of it — because there’s always a power imbalance in conflict — somebody else might say, we’re not talking about what happened last week; we’re talking about what’s been happening for years. And so the measurement of time itself is a site of conflict, a site of lament, a site of pain and a site of power. And there is necessity for enough safety to be able to have the measurements of those things in order to be able to talk in any way that might be fruitful.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

There’s a great subtlety and sophistication about how it is that memory occurs; when it is and where it is that we think a place was. “‘No, Ibrahim, the kitchen / is a little farther to the north,” one of them says to the other. And he’s recalling that the dad would’ve been sleeping on the couch and they’re arguing about where the kitchen was still by the end of the poem. This shows that people who are alongside each other also remember things differently.

In the context of a loving argument that you see depicted here, they’re able to hold their argument carefully about the past, about location, about how to draw a map and about how to divide a map. And so, it’s hard not to think that Mosab Abu Toha is saying this is what’s important, is that people from here should be involved in drawing the map, and there will be differences of opinion, but these differences of opinion will be held within the context of love and memory and who it is that was sleeping in a particular place, where it is that the kitchen was where it is that the mint was able to flourish, where it is that could be the site of hospitality.

The first time that I read this poem, I puzzled over the small stanza that says, “the mosque on the hilltop / calls for / prayer” just thinking that maybe that was adding some sonic texture to the poem. But then I looked again and thought, I suppose I see this entire poem as a prayer. This entire poem is people paying obeisance to land, paying obeisance to their bodies in the land, bending over and letting their hands touch the earth in the way that somebody might when they’re praying. And I think that this poem in itself is a demonstration about how it is that poetry and prayer and the desire for freedom and safety and a future — even the ghosts seem to have a desire for a future of land — that this poem is the manifestation of such a prayer and such a wish and such a yearning.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Ibrahim Abu Lughod and Brother in Yaffa” by Mosab Abu Toha

“The two walk toward the beach,

barefoot.

“With his soft

index finger,

Ibrahim starts to draw

a map

of what

used to be

their home.

“‘No, Ibrahim, the kitchen

is a little farther to the north.

Oh, don’t step over there,

Dad was sleeping there on the couch.’

“Tourist kids run by,

flying kites.

The waves hit

the beach,

shaded with cloud cover.

“The mosque on the hilltop

calls for

prayer.

“Ibrahim and his brother

still argue about where their kitchen was.

They both sit on the sand. Ibrahim

takes out a lighter, wishes he could make tea in their kitchen

for everyone on the beach.

Ibrahim looks upward to what used to be their kitchen window.

The mint no longer grows.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Ibrahim Abu Lughod and Brother in Yaffa” comes from Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza. Thank you to City Light who gave us permission to use Mosab’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Additional support for this mini-season of Poetry Unbound comes from:

Civic (Re)Solve — building communities of civic empowerment.

Quiet — listen and finish listening.

And The Hearthland Foundation — committed to justice, equity and connection, one creative act at a time.

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Cameron Musar, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s book, Poetry Unbound: Fifty Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections