Natasha Trethewey

Miscegenation

Were you born during a time when laws were different? What impact did those laws have on you?

In this poem, Natasha Trethewey recalls the story of how her parents crossed state lines to wed because Mississippi forbade interracial marriage at the time. It is written in the form of a ghazal, with birth and belonging, names and death coming together.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Natasha Trethewey served as U.S. Poet Laureate from 2012-2014. She is the author of a memoir, Memorial Drive, and five collections of poetry including Monument and Native Guard, for which she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host:My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the functions of poetry is to make you uncomfortable, is to face you with the truth and to face you with the truth put together in a form of art that challenges you. And certain poems make me realize that people who look like me and sound like me have done terrible things in many places, over many centuries.

[music: “Praise The Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

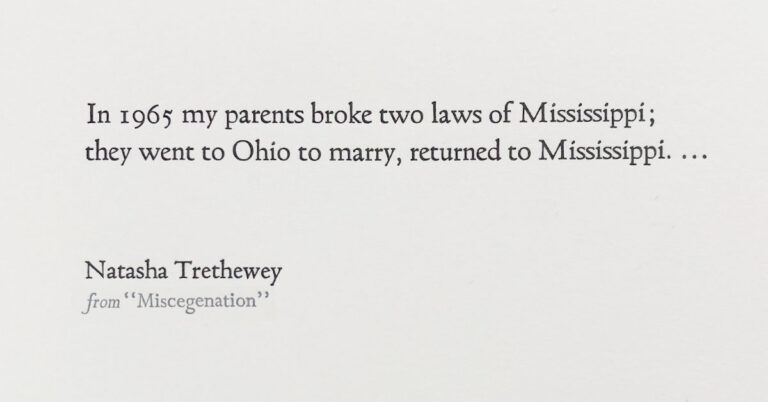

“Miscegenation” by Natasha Trethewey:

“In 1965 my parents broke two laws of Mississippi;

they went to Ohio to marry, returned to Mississippi.

They crossed the river into Cincinnati, a city whose name

begins with a sound like sin, the sound of wrong—mis in Mississippi.

A year later they moved to Canada, followed a route the same

as slaves, the train slicing the white glaze of winter, leaving Mississippi.

Faulkner’s Joe Christmas was born in winter, like Jesus, given his name

for the day he was left at the orphanage, his race unknown in Mississippi.

My father was reading War and Peace when he gave me my name.

I was born near Easter, 1966, in Mississippi.

When I turned 33 my father said, It’s your Jesus year—you’re the same

age he was when he died. It was spring, the hills green in Mississippi.

I know more than Joe Christmas did. Natasha is a Russian name—

though I’m not; it means Christmas child, even in Mississippi.”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Natasha Trethewey has spoken widely about coming from a mixed-race family with a white father and a Black mother, and how, depending as to who she was with, she felt treated differently. If she was out with her father, she might be perceived as passing for white. If she was out for her mother, she might be treated better than her mother, because she might have been perceived as “less Black” than her mother.

This poem is dense with references and history, and this poem makes reference to the fact that there was no miscegenation in Mississippi, and, also, there was another law, that you couldn’t leave to go to a state where there was such a provision, and return. That was also against the law. This poem refers to migration of enslaved people north, whether by force or choice, as well as the Great Migration. And then this poem references Faulkner’s novel and Russian literature, the gospel stories of Jesus, and the marriage of her parents, a mixed couple of a white father and a Black mother, and the story and meaning behind her first name. And if you were to say to somebody, “Combine all those things, as well as the years 1965, ’66, wintertime, Eastertime, spring, 33 years, age of death, and Christmas,” if you’d say to them, “In about 170 words, give us a poem that holds all that together,” you’d say, “That’s totally impossible.” But Natasha Trethewey has done this with such extraordinary skill that you feel like this word, Mississippi, holds all of these threads together.

[music: “Ashed To Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: She used the form of ghazal for this poem, because ghazal is a form written in couplets; there can be five couplets or up to 15 couplets. And each of the couplets’ two lines has to end with the same word, “Mississippi.” And she said that she’d had all these ideas about how to hold family stories together, the story of her name, the story of place, the story of laws. And she was never sure how to write that poem. And then, when she realized that a ghazal has these couplets, but the couplets don’t have to be directly following on from each other, they can seem like different threads that are held together with a repeated word. And so she used this beautiful form, which began in Arabic poetry and then has moved all across into South Asia, and you find it in many, many poetries of different countries, this beautiful form of a ghazal. And she holds all of these magnificent imaginations, and magnificent condemnations, too, of terrible laws, she holds it all together in this brilliant form of poetry.

In the middle of this poem, being a ghazal, is always supposed to include some reference to the poet’s name or their pen name, and Natasha Trethewey does this brilliantly. This poem also makes reference to the song “Mississippi Goddam,” released by Nina Simone in 1964, with this repeated line, “Everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam.” And she had sung that song in front of 10,000 people on the Selma to Montgomery marches. And the song was banned in many southern states; records that had been distributed to radio stations were sometimes returned to the distributor and snapped in half by the radio stations that wouldn’t play the record. And so you see that Natasha Trethewey has brought musical brilliance from Nina Simone, as well as poetic brilliance from the long tradition of ghazal, and held it all together in this amazing poem.

[music: “KeoKeo” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I find that this poem invites me to imagine what’s shaped me and to imagine what has impacted me and to imagine the laws that might have benefited me, were I born in the same part of the world as she was but have disadvantaged and have been prejudiced against other people. So this poem opens up questions about place and what place might mean to people, based on the perception of their race; the laws that have impacted them, as well as the traps from that laws.

I find myself looking at this and thinking of Irish migration to Mississippi and wondering what Irish names were involved in signing these terrible anti-miscegenation laws into place. This poem asks people to reflect on the stories that their families held dear, whether stories from religious or other literatures, as well as to think about the story of your name. This poem looks at the experience of an individual life, Natasha Trethewey — she’s tracing her own life through law, through literature, through her parents’ story, through her parents moving, through her parents settling — and looks at the world, as well as her life, through the lens of place and name.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Miscegenation” by Natasha Trethewey:

“In 1965 my parents broke two laws of Mississippi;

they went to Ohio to marry, returned to Mississippi.

They crossed the river into Cincinnati, a city whose name

begins with a sound like sin, the sound of wrong—mis in Mississippi.

A year later they moved to Canada, followed a route the same

as slaves, the train slicing the white glaze of winter, leaving Mississippi.

Faulkner’s Joe Christmas was born in winter, like Jesus, given his name

for the day he was left at the orphanage, his race unknown in Mississippi.

My father was reading War and Peace when he gave me my name.

I was born near Easter, 1966, in Mississippi.

When I turned 33 my father said, It’s your Jesus year—you’re the same

age he was when he died. It was spring, the hills green in Mississippi.

I know more than Joe Christmas did. Natasha is a Russian name—

though I’m not; it means Christmas child, even in Mississippi.”

[music: “Praise The Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Miscegenation” comes from Nathasha Trethewey’s book Native Guard. Thank you to HMH Books and Media who gave us permission to use Natasha’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

Poetry Unboundis Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me— find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections