Nithy Kasa

Blouse

An item of clothing — the blouse of a grandmother — is praised for its artistry, is remembered for how it sits on the body. And then, having been lost, is remade, refined, and reimagined on a new body that recalls the bodies of women of previous generations.

We’re pleased to offer Nithy Kasa’s poem, and invite you to connect with Poetry Unbound throughout this season.

Image by Annisa Hale/ Film processed by Moody's Film Lab, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

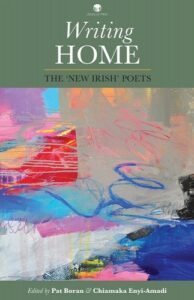

Nithy Kasa is a Dublin-based poet of Congolese origin. Published in poetry magazines such as Poetry Ireland Review and anthologies like Dedalus Press’s Writing Home: The New Irish Poets, her work can also be found in the archive of the University of Galway and University College Dublin special collections. Her debut collection of poetry, Palm Wine Tapper and The Boy at Jericho (Doire Press, 2022), was listed among the top poetry books of 2022 by The Irish Times.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I’m told that apparently, I resemble in character my great-great-grandfather, obviously a man who I never met. The story in the family about him is that he did like to talk and he enjoyed wandering. And people have said to me that I am somehow some kind of reflection of him a few generations later.

And I mean, lots of people like to talk and lots of people like to wander. So I don’t know that there’s anything particular in it, but I’ve chosen to take the DNA of it and the connection of it and to let it be true from me. Me and this connection with a man who was probably born in 1840 somehow, not only in DNA but also in character, we’re echoes of each other in personality. And I find companionship with him, even though I know I’ll never meet him.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Blouse” by Nithy Kasa

“Mother had a blouse. It was mauve

with puff-sleeves. Roped shoulders

with pads under. The collar Peter Pan.

The style of the forties. They stitched Devil’s

Ivies on the breasts like purple hearts.

Dark sequinned patterns on a plain torso,

sewn to please. Lines swamping, as if the maker

had something to say. Or may have failed

the first twists seamed, so overran them.

The blouse belonged to my grandmother,

who inherited it at sixteen, from her mother.

Because it did not survive, I bought myself one:

mauve, puff-sleeves. The collar Peter Pan,

like a rifle bird at dance. I altered it, V-necked,

glammed. My scaffolded consciousness,

imitating the hands that came before.

The domes on the cuffs too were my own doing.

I caught myself, strutting my mother’s walk,

first day I had it on. It runs in the family,

women with pretty faces,

warm smiles, curls on their circlets.

The poppies on their skins worn elegantly.

At night, I doffed the blouse, naked —

myself in the mirror, one eye shy,

counting the pleats on my skirt,

a man waiting on my bed.

His bust, like that of my grandfather’s,

His tongue poetic, like my father’s,

before mother had me.

Crystal pieces passed on,

the star-lights, on my ears.”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

In a way, this poem is being set up where the blouse is going to be spoken of as an heirloom. So right from the word go, “mother had a blouse,” and the description of it and the reflection of that to the grandmother and the great-grandmother, you assume that this blouse is now going to be worn by the poet. And we’re going to hear how the blouse has maybe been mended by the poet and how the blouse is a holder onto something. And the blouse itself is an object that holds generations, and stories, and skin cells in it.

What’s so interesting is this line, not even halfway through the poem: “Because it did not survive, I bought myself one.” The blouse didn’t survive, and we don’t know what that means. Certainly, it just means it’s not here now. Nithy Kasa moved from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Ireland as a teenager, and so does it mean it just got lost along the way? Does it mean that it had been discarded beforehand? It has been brought into the poem, though. And what else has been brought into the poem? Connections with parents and grandparents and great-grandparents. Connections with artistry and craft and skill. Connections with culture.

I love the replacing of the idea of the exact blouse being the exact thing that carries memory to the memory being the thing that cultivates and creates and connects and holds her in a line, even though the line’s been broken by the blouse not having survived. Nonetheless, there’s something recoverable. She can make it, and not only a perfect replica, she makes it her own, and she makes it her own personality, and what has not survived is recreated and repurposed. Not just in the blouse, but also in herself.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

This poem blends references to generations before — mother, father, grandmother, great-grandmother, grandfather — it blends that with reflections on the body and sensuality and the bodies from which bodies come. The collar of the blouse, the Peter Pan collar, is described with a simile toward the end of the poem “being like the mating dance of a rifle bird.” And the rifle bird holds its wings above its head, curved wings that meet at the front, the way that a curved collar would when the collar is closed. And this mating dance and the meeting of the collars in the middle is a way within which sex and generations before her are held together in this brilliant poem. There’s sensuality, there is body, there is “his bust like that of my grandfather’s. / His tongue poetic, like my father’s.” There’s the fact that the blouse is on her own naked skin, “At night, I doffed the blouse, naked.” And she’s got “one eye shy.” But the other eye, where’s that? Looking back to the past, looking at the lover, looking at herself, looking at generations, and looking at everything that’s meant that she’s here now.

[music: “The Edge of All There Is” by Gautam Srikishan]

Sometimes when I read a poem, I find myself thinking, “You know, it could end there and it would be a perfect poem.” And that’s what I thought was going to happen. When I got to the line, “The domes of the cuff too were my own doing,” I thought the whole poem was going to be about the way that something didn’t survive and then was rebought and brought into something. And when I got to that line I thought, “Oh, this is where I thought it was going to end. But yet there’s plenty more.” What happens is the poem goes onto this new direction. Rather than attention to the garment on the body and the bodies that made the garment, it’s attention to the body that is wearing the garment: her own. And she becomes her mother in her walk, strutting, and she sees the links between herself and her family: “It runs in the family, / women with pretty faces, / warm smiles, curls in their circlets.” But that line, “it runs in the family,” is a reclamation to say, what runs in the family? The blouse, the color of it, what happens to yourself when you wear it, and perhaps, too, the capacity to change and remake and to feel in a lineage that has had to go through change and has nonetheless remained the same despite the changes that have happened.

This poem is in two halves, really. One about the garment and the other, about the bodies that have worn the garment.

[music: “Dust of Summer” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Blouse” by Nithy Kasa

“Mother had a blouse. It was mauve

with puff-sleeves. Roped shoulders

with pads under. The collar Peter Pan.

The style of the forties. They stitched Devil’s

Ivies on the breasts like purple hearts.

Dark sequinned patterns on a plain torso,

sewn to please. Lines swamping, as if the maker

had something to say. Or may have failed

the first twists seamed, so overran them.

The blouse belonged to my grandmother,

who inherited it at sixteen, from her mother.

Because it did not survive, I bought myself one:

mauve, puff-sleeves. The collar Peter Pan,

like a rifle bird at dance. I altered it, V-necked,

glammed. My scaffolded consciousness,

imitating the hands that came before.

The domes on the cuffs too were my own doing.

I caught myself, strutting my mother’s walk,

first day I had it on. It runs in the family,

women with pretty faces,

warm smiles, curls on their circlets.

The poppies on their skins worn elegantly.

At night, I doffed the blouse, naked —

myself in the mirror, one eye shy,

counting the pleats on my skirt,

a man waiting on my bed.

His bust, like that of my grandfather’s,

His tongue poetic, like my father’s,

before mother had me.

Crystal pieces passed on,

the star-lights, on my ears.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Blouse” comes from Nithy Kasa’s book Palm Wine Tapper and The Boy at Jericho. Thank you to Doire Press and Nithy who gave us permission to use her poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Amy Chatelaine, Kayla Edwards, Annisa Hale, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s new book, Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections