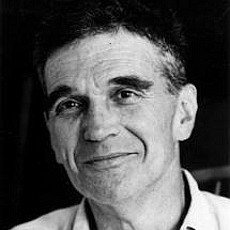

Robert Coles

The Inner Lives of Children

Psychiatrist Robert Coles has spent his career exploring the inner lives of children. He says children are witnesses to the fullness of our humanity; they are keenly attuned to the darkness as well as the light of life; and they can teach us about living honestly, searchingly and courageously if we let them.

Image by Rami Efal/Flickr, Attribution.

Guest

Robert Coles is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Medical Humanities at Harvard Medical School. He's the author of many books, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning series Children of Crisis and The Moral Intelligence of Children and The Spiritual Intelligence of Children.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, for the first time, we feature a wide-ranging conversation I had with child psychiatrist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robert Coles in his Boston living room in the year 2000. He says that our children can teach us about living searchingly and gracefully even in hardship if we will let them. We explore what he’s learned across a lifetime of listening to children and how that’s formed his sense of the deepest meaning of religion and of humanity at every age.

DR. ROBERT COLES: The spirit of religion I think is what children connect with: the questions, the inquiry, the enormous curiosity about this universe, and the hope that somehow those answers will come about.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. In the early days of Speaking of Faith, I sat down for a wide-ranging conversation with Harvard psychiatrist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robert Coles in the living room of his Boston home. He is best known for his unparalleled research on the inner lives of children. This year my producers and I listened again to that interview with Robert Coles, most of which had never been aired, and we found it enduringly resonant.

It was a different world in which I spoke with him: the summer of 2000, a period of relative peace and prosperity in the U.S. Yet one of the strongest points Robert Coles made with me then was that we err when we try to create an illusion of a perfect world for ourselves and our children. They are witnesses to the fullness of our humanity. They are keenly attuned to the darkness as well as the light of life, and they can teach us about living honestly, searchingly, and courageously if we let them.

DR. COLES: They may be brought up in a secular world, but they have deep inner sides to them that are non-secular in nature, which have to do with eternal questions of what’s right and what’s wrong. You might call them verity and evil or whatever, but children do come up with that, amazingly, while they’re witnessing it. And they’re holding on to it and they’re asking why and they’re wondering about things. And that is a very important part of childhood and maybe an important part of all of our lives.

MS. TIPPETT: From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas.

Today, “The Inner Lives of Children: A Conversation with Robert Coles.” Robert Coles found his personal calling in a crucible of American social change. One day in 1960, as a young psychiatrist working in New Orleans, he happened to drive by crowds of adults heckling a first-grader, Ruby Bridges. She was one of four children to integrate New Orleans public schools and the only black child to enter the William Frantz Elementary School that year.

Robert Coles was stunned by the evident dignity and apparent wisdom with which she comported herself. “Had I not been right there,” he wrote later, “I might’ve pursued a different life.” But Robert Coles got to know Ruby Bridges and her family, and over the next two decades he listened to children all over the world.

He wrote books about the psychological, political, and moral lives of children. In 1973, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his series “Children of Crisis.” Then one day late in his career, Robert Coles’s friend Anna Freud suggested that he might look back at all his research and see if there was anything he’d missed. And he found, to his surprise, that his notes were full of religious and spiritual observations from children, insights he’d largely ignored for the sake of academic respectability. Those observations were the impetus for his 1990 classic work, The Spiritual Life of Children.

Robert Coles’s own formative religious background was confusing, as he put it to me when we began to speak. His mother was a devout Episcopalian from the Midwest. His father was a half-Catholic, half-Jewish Englishman. He was a scientist and an atheist, though in the years of Robert Coles’s childhood, his father’s Jewish identity was coming painfully into relief with the rise of fascism in Europe.

DR. COLES: My father would drive us to church. He’d sit and read the newspaper. He wouldn’t go into the church. He’d read the Sunday Times and then we’d come out and he’d ask my brother and me what we learned. Interesting verb. And I wonder — I remember asking my mother, I must’ve been seven or eight years old, “Why doesn’t Daddy come into church?” She said, “Well, your father doesn’t believe in what he would hear here.” So when she said that, that was an invitation to me to be skeptical.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. COLES: Because, you know, I was his son and I very much looked up to him. So I want to know why doesn’t Daddy believe this, and that got the whole thing going, because he explained to me that what he believed in is understanding predictability through science and all its achievements. So I distinctly remember in the sixth grade, that would make me 10 years old, understanding the position of the agnostic skeptic as well as the faithful believer. I had it in my bones and I had it in family experience. And very important, what I had was my mother and father, memories of my parents talking to one another out loud so that my brother and I could hear and understand their different points of view.

And I remember my mother telling me, oh, do I remember this, I remember my mother telling me that when I heard people saying things that were anti-Semitic or slurring against Jewish people or toward any people, I remember her saying hate is a sin. And then of course she reminded us that Jesus was a Jew. In fact, what she said then, even now I can remember, she said he had the courage to believe and to stand up for his beliefs and even to die for his beliefs. And that rebellious side of Jesus I think my mother held onto with great passion. And I think it’s tragic in a way that all too many of us allow ourselves to become so conventionally religious that we lose that, shall I say, skeptical, rebellious, questioning side to religion.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: Which I think is what I’m trying to say here as I speak with you, as I go back to my parents and to my childhood and try to recapture some of that spirit that I knew as a boy.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s interesting to me that those words you used, “questioning spirit,” and not a conventional religious sense are also qualities that you found in children and even in children who came from homes in which the tradition was much more set.

DR. COLES: That’s a very good point you’ve just brought up. Children are by nature questioning. I mean, I know it as a pediatrician and a child psychiatrist. I know it as a parent. I think we all know that children are questioning. And I think there is no doubt that a lot of the religious side of childhood is a merger of the natural curiosity and interest the children have in the world with the natural interest and curiosity that religion has about the world, because that’s what religion is.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: It’s our effort in this planet as creatures who have a mind and use language to ask questions and answer them through speculation, through story-telling, to explore the universe and answer those fundamental questions: Where do we come from? What are we? And where, if any place, are we going? And those fundamental questions inform religious life and inform the lives of children as children, and that merger is a beautiful thing to behold when you’re with children.

MS. TIPPETT: You know what’s nice about what you just said to me too, is I suddenly realized that what you discovered in speaking with these children and listening to them is not only revealing about childhood but it’s revealing of an aspect of religion which we probably don’t pay as much attention to as we should.

DR. COLES: That’s the great tragedy, isn’t it?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: Because after all, if you stop and think about Judaism, the great figures in Judaism are those prophets of Israel, Jeremiah and Isaiah and Amos. They were prophetic figures who asked the deepest kinds of questions and were willing to stand outside the gates of power and privilege in order to keep asking those questions. And then came Jesus of Nazareth who was a teacher. You might call him the migrant teacher who walked about ancient Israel — now called Israel, Palestine, whatever, the Middle East — seeking and asking and wondering and reaching out to people and daring to ask questions that others had been taught not to ask or even forbidden to ask. And this kind of inquiring Jesus, this soulful Jesus, searching for comrades and, let’s call them in our vernacular, buddies. They were his buddies, and they were willing to link arms with him in this kind of spiritual quest that he found himself, shall we say, impelled toward or driven toward. I don’t want to use driven in any psychoanalytic way …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: … but just in a human way. And this was the rabbi, the teacher, the exalted figure, a descendant, really, of Jeremiah and Isaiah and Amos. It’s that prophetic tradition of Judaism which is so profound and important and which the Christian world is, at its best, the beneficiary of.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: Now, both in Judaism and Christianity, of course, there are rule setters, and at times they can be all too insistent, some would say even a bit tyrannical. But in any event, the spirit or religion, I think, is what children connect with.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: The questions, the inquiry, the enormous curiosity about this universe, and the hope that somehow those answers will come about, which is what we do when we kneel in a church and sit and pray in a synagogue or whatever.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Also what I think you’re getting at there and what is also in this compatibility between children and religion also has something to do with, I mean, there’s something mysterious in it as well, something about the mystery of those questions.

MR. COLES: Mystery is such an important part of it. And mystery invites curiosity and inquiry. You know, Flannery O’Connor — talk about a religious person, she was Catholic in background but she was beyond Catholicism; she was a deeply spiritual person. And she once was talking about the kind of person who becomes a good novelist, hoping that she would be included in that company but not daring to assume that that had happened. But once she said, beautifully — it’s in her letters if the listeners want to get one of her books. It’s called, The Habit of Being — but in one of those letters she says, “The task of the novelist is to deepen mystery.” And then she pauses and she says, “But mystery is a great embarrassment to the modern mind.” And there’s our tragedy, that we have to resolve all mystery. We can’t let it be. We can’t rejoice in it. We can’t celebrate it. We can’t affirm it as an aspect of our lives because, after all, mystery is an aspect of our lives.

We come out of nowhere, don’t we, in the sense that we’re a total accident. Our parents met. There’s the accident. And, you know, we’re born. Obviously, we come from someplace physiologically. And then comes the emergence of our being, which is the psychological and spiritual emergence of our being that takes time, experience, education of a certain kind with parents and neighbors and teachers and relatives and from one another humanly. And this slow emergence of our psychological being and our spiritual being is itself a great mystery. And mystery, you bet — mystery is a great challenge. It’s an invitation, and it’s a wonderful companion, actually.

MS. TIPPETT: Child psychiatrist and author Robert Coles.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Inner Lives of Children: A Conversation with Robert Coles.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Let me ask you about something that intrigues me in your work and also in other kinds of work around children and around their spiritual lives in particular, that this curiosity and this ability to connect with the mystery and to be wise about it in a way, seems to be there in very young children and in many kinds of children in many circumstances, both good and bad. And then there comes an age, which might be nine or 12 where, again, sort of in many kinds of children in many circumstances, they become more like us, like adults. How do you make sense of that? Are children somehow born closer to God? I mean, that’s one way some people would say it. In all the work you have done, how would you describe what’s happening?

DR. COLES: Well, that’s a question not only about spirituality, but maybe psychology too, because I know from my own experiences as a parent and now as a grandparent, I have two grandsons and I watch them and I see their spontaneity, their curiosity, let me even call it their delving spirit. They’re probing. They want to know. Almost physically they poke around and explore and touch things. They want to know. They want to understand. They’re yearning. This is just part of their being. And if they lose that at home and school, this, of course, and in the neighborhood, this can be a tragedy. But I think insofar as that curiosity is allowed to flourish and is encouraged — not encouraged ritualistically or compulsively, but just celebrated and enjoyed by the adult world — this brings them toward religion.

Because I know children. I’ve taught in a Sunday school, and the children ask me, for instance, “Why are you teaching?” and I say, “Well, I’m teaching so I can learn from you about God.” “Well, I don’t know anything about God,” they’ll say. “Well, what do you know,” I say, “about God?” “Well, I know that God created the world.” How did he do that?” Other children ask; this isn’t me as a teacher in Sunday school. “Well, he decided he wanted company.” Listen to that, I heard from one girl. She said, “He decided he wanted company.” “Well, why did he want company?” “He just wanted some people around him that he could talk with and learn from,” she said. I was stunned. If that isn’t the whole existentialist tradition, I don’t know what is. And she had it right there in the palm of her hand. God’s search for meaning, which is what some of the existentialists, philosophically sophisticated writers have told us, but she was just being natural, intuitive, human, and attributing to God her own, of course, search for understanding and companionship and a meeting of minds.

It’s wonderful to be in a classroom sponsored by a church or a synagogue and realize that there it is. Children and the prophets of Israel and Jesus of Nazareth all and his buddies, if I may use that word again, searching for answers about what are we doing here and how should we spend our time here? What’s important?

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: And these children know this out of their humanity. They’re trying to figure out what the world is like. And they’re trying to figure out, among other things, their own parents. In fact, one boy said to me, “You know, my parents worry a lot.” So I said, “Oh?” He said, “Well, they’re always worrying about everything.” And then he brought up the questions of money and education, but he said, “I think that they’re just worrying that they should really stay around and be with us.” So I thought that was interesting. I said, “Is there any reason, do you think, that they’re worried about that?” He said, “My father lost his brother.” And this just became a poignant story about frailty and loss. “After my father’s brother died, my father became more religious,” this boy said to me. And then I realized, there he’s making that eternal connection between suffering and loss and vulnerability and faith, or the search for faith, or the search for meaning, especially if you’ve been hurt or you’ve lost someone.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, now, there’s that mystery again too, I think.

DR. COLES: There’s that mystery.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s something that children have that also adults sometimes grasp in the midst of suffering or when they face death.

DR. COLES: And suffering is both mystery and common human experience, isn’t it? And religion is there to help us ponder suffering and its significance to us and, indeed, even redemption. Redemption means that out of suffering can come strength, understanding, reflection. And that same boy that I just mentioned, he said, “You know, after my father lost his brother, he started thinking a lot about the world.” And I thought there’s a redemptive response, that the boy isn’t using a fancy word like redemptive, but he’s getting right down there into the nitty-gritty as religious experience as a consequence or post-mood to human experience equals frailty, suffering, despair, loss, injury, vulnerability, those words. Which of course the Bible’s filled with stories about, isn’t it?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: And I might add also storytelling. We’re the storytelling creature. We are the creature of language and narration. We want to tell about what we remember and tell stories, and that’s what the Bible says, “Yes, indeed. That’s how you understand the word. You tell stories to one another.”

MS. TIPPETT: You know, now that’s interesting, to think about how storytelling is so much at the heart of all of our traditions. Like, I can’t at the moment — there may be some, but I can’t think of a religious tradition which doesn’t have storytelling at its heart. And, I mean, is that perhaps a connection that children have? Because they know how to listen to stories.

DR. COLES: They know how to listen. They know how to be told stories.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: They’re told stories all the time.

MS. TIPPETT: And we lose that, don’t we?

DR. COLES: That’s right. They go to bed and they’re told stories. They wake up, they’re told additional stories and the world becomes a series of unfolding stories that come to them. And of course the Bible, reflecting that as an echo of that in the strongest sense of the word echo, as an echoing presence, the Bible says, here are some stories, stories of meaning, stories of loss, stories that are redemptive in nature, because they’ll touch you to the bone and to the quick. Even as we ourselves are a story of struggle and hope, but also we have our downsides.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. It’s not all happily ever after.

DR. COLES: No. We have our downsides struggling with our upside, all of us.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: So as we grow older, we don’t just stop being tellers and listeners of stories, but in that process we also lose a sense of how stories convey truth.

DR. COLES: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: Which is what our traditions try to preserve for us.

DR. COLES: We hope so. And if we lose that then we’re in a different kind of jeopardy. I mean, then that’s what it is to be lost. To be lost in such a way that you don’t have any stories to think about and fall back on and that you wander around in your own self without any larger frame of reference or purpose or meaning.

I wrote a book called The Call of Stories, and boy, did I mean that, because stories call us. And of course that’s what religion is. It’s stories, in the best sense of the word story, calling to us. Events, these are larger-than-life figures who took part in larger-than-life human drama. There’s no question. I mean, if start thinking of what went on between Abraham and Isaac, which Kierkegaard talked about a Christian echo of Jewish experience. Kierkegaard knew how important that was, that a father could say to a son, you know, “If necessary, even the loss of your life.” I mean, it stuns us. I think some early Judaism comes so powerfully to the point of human drama, you know, and possibility.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. And I think that — I know from my own children also that it’s not just that they are curious but that their imaginations are so alive. I mean, drama is something they are given to naturally.

DR. COLES: And they’re ready for that, aren’t they?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: And they’re ready for it and they’re interested in it. And of course they’re interested in a lot of things that a lot of us are not so willing to talk about. I’ve had children in Sunday school ask me about the Virgin Mary, and they want to know about the mystery of Jesus’ appearance among us and, boy, they want to get down to all kinds of details. And I try to bring us to a more lyrical and symbolic level, which is, I think, what the Bible intends, although who am I to speak about what the Bible intends? But the figures in the Bible, men and women, older people, children, they all tell us about the world we’re a part of, and they tell us about ourselves. And children know this. They just know it in their bones. And they’ll speak it out.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Robert Coles’s warm and wise presence was on full display during his 2008 Lowell Lecture at Harvard University. In the filmed talk, he shares what he’s learned from children in crisis across the world, and he recounts the moving details of his first encounter with six-year-old Ruby Bridges during the desegregation of her school in New Orleans in 1960. Watch selections from his lecture at speakingoffaith.org and see Robert Coles’s vitality and humor for yourself.

Also, while producing this show, we posted a number of behind-the-scenes entries on SOF Observed, our staff blog, including video of an editorial session and a post about how this interview with Robert Coles found new life after eight years.

Find links to all this and more on our homepage, speakingoffaith.org.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: After a short break, more conversation with Robert Coles, including his observations of qualities of childhood that mark adult lives of leadership.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Inner Lives of Children.” For the first time, we’re featuring a wide-ranging conversation I had with renowned child psychiatrist Robert Coles in his Boston living room in the year 2000. We’re exploring what he has learned across a lifetime of listening to children and how that formed his approach to the meaning of religion and humanity at every age.

Robert Coles won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for his book series Children of Crisis, which emerged from his studies of how children in the 1960s and 1970s developed in times of social upheaval. He is now 79 and retired from Harvard, but still writing and speaking. His classic 1990 work, The Spiritual Life of Children, is still widely read and studied. For that book, Robert Coles spent thousands of hours interviewing children around the world, including children of migrant farm workers, Hopi children, and Swedish children, Pakistani children living in London, and children of affluence in his own Boston backyard.

DR. COLES: I worked in Israel too when I was doing the spiritual life book and the whole effort involved in it. I talked with children in all parts of the world, but I made a point of going to Israel and talking with the children there, Jewish children, Christian children living in Israel, and Arab children living in Israel, a religion I know very little about. But of course there are certain convergences that bring together Judaism, Christianity, and the Mohammedan world.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me about those that you observed in speaking with children.

DR. COLES: Well, the convergences have to do with God and the mystery. The convergences, by the way, are also calendar-like in nature. The humanity of us all that connects to calendars, to the end of the year, the beginning of the year.

MS. TIPPETT: To our need for ritual.

DR. COLES: And for holidays and the importance of a holiday as means of marking time and pondering and reflecting. What the religions say to us is this is what we share as human beings and this, by the way, is what children pick up very quickly. They know. They know. They know the origins of this and our origins, you know. The connection of all of this, by the way, to eating, what foods you eat sitting around a table, of prayer as an aspect of our urgent human need to hope and to settle things with the unpredictability of the fatefulness of life — which is where mystery comes into this — the fatefulness of life, which is around any corner, isn’t it …

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: … for all of us.

MS. TIPPETT: So the convergence is there. And I’m also intrigued in your work in how the differences come out. For example, you’ve often had children drawing pictures, and it sounds like children have great pride and ownership of the pictures they draw and the things they understand.

DR. COLES: They sure do.

MS. TIPPETT: When they look at …

DR. COLES: By the way, talk about children and drawing. I’ve asked them if they want to draw a picture of how you would represent God. Well, they turn to me and say, “No, you don’t. You can’t picture God.” “Well, you can,” I’ll say, repeating what they said to me. “You can’t do it, because God is not in a picture.” “Well, where is God?” Listen to the theology that’s getting going here between me and them. They’ll say, “Well, he’s beyond. Beyond.” And then I had a kid say to another kid, “Well, where is he beyond? Is he in the sky? Is he up there near the stars?” Of course, these are the questions we all ask. Then I’ve had girls say, “How about she? God is a she.” “God is a he.” “Well, God is God,” I’ve had kids say to settle the argument, which is quite beautiful. God is God. And they put in their pictures, boy do they, they put in their pictures the emotions and the stories that they’ve learned as a result of their religious experience in churches in synagogues.

Now, in the Jewish religion, they’re told you don’t represent by pictures God, of course. But then I’ve had children say, “You don’t represent him in pictures, but you can think of him,” they’ll say. “Yes.” “You can talk about him?” “Well, he must look like something,” I heard in a synagogue in a school there, “but we can’t tell you what he looks like.” Which is a good way of settling it theologically.

You know, in a way when they settle these things theologically, they’re settling it the way that theology had to settle it. I mean, if the rules are and if the experience is this is almost unfathomable and it’s beyond understanding, then you settle it that way finally, even when you’re thinking of drawing pictures.

But they draw pictures of people of power and influence, evocative pictures that render the evocative nature of religious experience, the mystery of it all.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if in your career you’ve encountered skeptics who wonder whether the children you speak with haven’t somehow been trained to talk about God through their environment or through their families. But I think that in what I’ve read you also find that children who are living in very secular environments are making these same kinds of observations and asking questions which are essentially spiritual questions. Is that right?

DR. COLES: Yes. I think it’s an aspect of their human nature. They may be brought up in a secular world but they have deep inner sides to them that are non-secular in nature, which have to do with eternal questions of what’s right and what’s wrong. You might call them verity or evil or whatever, but children do come up with that amazingly at times in which they ask even about their own parents: “I wonder why my parents struggled so hard to get into this neighborhood.” And then they say to one another they forgot what really matters. Now, when you hear a child saying that they heard their parents say that, they’re remembering something. They’re remembering moral conflict and struggle, or they’re witnessing it and they’re holding on to it. And in that sense, children of course are witnesses.

And this witness that children have naturally within a family, within the developing institutional world that they meet when they’re taken to the stores, to the marketplaces, and of course start attending school, they’re witnesses. They’re outsiders who are learning certain ways of being. But they also have a critical side to them as all outsiders do, and they’re asking why and they’re wondering about things. And that is a very important part of childhood and may be an important part of all of our lives as we try to reason with ourselves about what is called necessary and important and what may not be so desirable or may even be wicked, if I may use a biblical kind of word, wicked.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve also done a great deal of research and writing, not just on the spiritual life of children but the moral life of children and the political life of children. How would you describe after all of the thinking and work you’ve done the relationship between the political and moral and spiritual lives of children?

DR. COLES: Those are words I use which describe an aspect of human experience, but they merge. Politics has to do ultimately not only with place and power and governmental identification and the flag and loyalty to a certain country’s history, but politics also has to do with morality, because it has certain principles, the rules of the Constitution, of the Bill of Rights, or whatever, the laws of the land, so to speak.

So the political life begins to connect in its own way with the religious and moral life of those people who are living in a certain nation. And what I did is I asked children about what is America. What do you think America stands for? Because I want to find out what it means to children to feel American and to speak as they feel an American should speak. But I also, in listening to this pretty soon here, coming up with being an American, as they talk, means being a good person versus a bad person and maybe even means living this way rather than that way, which in turn connects with their religious and spiritual beliefs, certainly with their moral beliefs. And on and on it goes.

MS. TIPPETT: Child psychiatrist and author Robert Coles. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Inner Lives of Children: A Conversation with Robert Coles.”

In addition to his work with and about children, he has also befriended and written about exceptional adults in his long career, among them the poet and physician William Carlos Williams, musician Bruce Springsteen, and Catholic social activist Dorothy Day.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m really struck in the sort of breadth of your writing that you have not only been observing and influenced by wise children, but also there’s some wise adult figures, who recur in your writings. Dorothy Day is the one that comes to mind, but there are others. In particular, when I read what you have written about her, you talk about a quality that she had of noticing and wondering and taking things and people sort of at face value. And so I wonder if you make a correlation between adults whom you admire and let’s say lives of moral leadership and some of these qualities of the children you’ve studied.

DR. COLES: Oh, very much so. If I may be a little sweeping in a generalization, with all due respect to Dorothy Day and some of the others I’ve met, there’s nothing that they possess, and I’m sure they would admit it, that isn’t part of their childhood and of the childhood of all of us. Namely, searching, wondering, asking, questioning, and maybe sometimes falling flat on one’s face. Because Dorothy Day used to talk that way remembering her own childhood and talking about other people.

Now, I would mention here, if I may, that some of the most remarkable people I’ve met, referring to your observation of adults, of parents and whatever, I met in the course of working with children. I met people that were connected to those children. There’s a book I wrote, it’s called The Old Ones of New Mexico, if you’ll pardon me mentioning a book I wrote, but it’s about elderly people in northern New Mexico. And I met them because I was talking with children of Spanish-speaking background. But I found that some of their grandparents, especially these elderly people, were remarkable people. Wise and thoughtful. They didn’t go to high school even, let alone college, but boy, they were smart and very thoughtful, and I wanted to celebrate that. I wanted to listen to them and I offered their words to the public as a writer who listens and uses the tape recorder as you’re using now. But I wanted to acknowledge myself to them and acknowledge to other people that children have companions in grandparents and in parents and in teachers, in adults.

MS. TIPPETT: But I wonder, do you see — is there some capacity of people who you’ve observed to be wise at an older age …

DR. COLES: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … have they been able to somehow retain or live into some of these qualities of childhood?

DR. COLES: Yes, I think you’re right. I think that that’s the challenge to all of us, not to forget our childhood and to forget its possibilities. You can be law abiding, but also, one hopes and prays, spontaneous and your own person and willing to even break some rules that you think ought to be broken. Not in order to be a pain in the neck or a lawless person, but in order to capture your own individual particularity and spontaneity. That’s where children have: a spontaneous ongoing direction that is theirs. Let’s restrain ourselves as we endeavor to work with our children to help them to be a bit more civil sometimes, but let’s not banish from them the positive side of childhood, its yearning interest in the world, almost unquenchable appetite for finding out about things and experiencing them. Not in order to be lawless or difficult or self-indulgent, but in order to explore this universe which is our task. Isn’t that what religions tell us? To explore the world and to realize and fulfill our individual humanity as citizens of this planet lucky enough to be here, given that chance for a few years of human experience, which is what a life is.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Those spiritual questions that you describe that children ask are really the questions of what does it mean to be human, aren’t they? To be fully human.

DR. COLES: All the time they ask these questions. Unfortunately, some of us think we ought to stop them from asking them, probably, because we’re made uncomfortable by the questions.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: But I hope we are made uncomfortable when they stop asking the questions, because those questions really mean something. Why is this world this way? Why do people say these things to other people? Why can’t people — as one girl said to me in a class, the fourth grade, she said, “Why can’t people get along better with one another?” And I heard that question, I thought, oh, boy, she should be president of the United States.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, if you think about it, if she follows that question …

DR. COLES: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: If she starts there and spends her life pursuing that question and working out answers to that question that could be profound, couldn’t it?

DR. COLES: Well, let’s hope she continues to ask it.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: And let’s hope we continue to listen to it and try to answer it for ourselves. I mean, it’s a gift to ask a question like that. It’s a gift to hear the question posed, and then it’s a challenge to try to find the answer for her and for us.

MS. TIPPETT: Child psychiatrist and author Robert Coles. I sat in his living room in the summer of 2000 when terrorism, U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, and economic crisis were, for Americans, part of an unimaginable future. Yet even then Robert Coles sounded a note of cautious realism that is all the more instructive now.

DR. COLES: Let’s face it. This is a pretty lucky time in American history. We’ve got a solid economy. We’re not in the midst of a war nor have we been recently. And this has been a time — talk about privileged ones — this is a time of privilege for the nation in which we’re not losing people in wars and we’re not, by and large, having our country suffer a severe economic crisis and depravation that goes with such an economic crisis. So against that background things aren’t quite as bad, certainly, as they were in the 1930s, for instance, when Hitler threatened the whole Western world, the whole world itself, and beyond Hitler there was the Great Depression that afflicted a number of the Western democratic nations.

On the other hand, I think, look, every generation of Americans and of people on the planet has to struggle with the possibility of sudden danger, sudden evil, sudden monstrousness of one kind or another. So there is possibility of danger that we have to think about and, by the way, bring up our children to know how to deal with and to accept as in some way around a corner possibly for them and for us. That’s why children who, after all, know about the world, they listen to the radio, they watch television, they hear their parents talk …

MS. TIPPETT: But you’re saying again these are these realities which we always have lived with.

DR. COLES: I am afraid so.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. COLES: I don’t want to be gloomy and too pessimistic, but I think, you know, this is what Freud knew. This is why Freud stirred up a lot of criticism, because he acknowledged that there — well, he acknowledged, really, what the Bible acknowledges: that there is an evil side to people, and maybe it’s inescapable. But he also said, let’s try to understand it, and maybe through our rational and decent sides we can overcome that or at least hold it in abeyance or keep it under some kind of control, which is every human being’s task, I would say, if I may be a bit of a moralist. Which I hope we all are with ourselves and with respect to one another, that we have to keep waging the struggle, whether you want to call it against original sin, against the unconscious and its willful evil side. No matter what language you use, whether it be secular or religious, this is a human struggle, to be somewhat honorable and decent knowing that it is a struggle to keep that going. Because there are moody, unsettling times when we become all too self-serving if not greedy, if not refusing in our prejudicial manner. And let us hope and pray we win that struggle overall in our lives, which is what the religions tell us. Keep struggling, because you’ll be judged at the end.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. COLES: And they’re right. We are judged at the end, whether you want to take it literally and take it judged by the Almighty in a certain mysterious location and manner that is beyond our factual imagination. But nevertheless, we are judged by ourselves and by those we leave when we are dying. Because, you know, they say, well, this is the kind of life he or she lived, and I’m thinking about it now in retrospect and in summation.

MS. TIPPETT: All right. Here’s my last question.

DR. COLES: OK.

MS. TIPPETT: This is my last question. I’m wondering what pieces of these spiritual insights and wisdom of children have most affected and informed your own evolving understanding of how life is to be lived?

DR. COLES: Well, I think I’d respond to that question by saying those questions that they ask I think have helped me to ask my own questions about how I ought to live and what I ought to do and what matters. And that’s the gift the children offer us in homes, but also I would say in the work I do. I leave some of the classrooms or homes that I’ve visited in the course of this research and I’m kind of shaking my head a little bit. I sometimes have even stopped the car as I drive away, stop a mile later down the road, and I just think about what I’ve heard from those children and try to say to myself, remember that. Remember those questions. Remember their interest. Remember their unflagging determination to find answers and to figure things out. You should be trying to figure things out. Try to connect yourself to some of that freewheeling adventuresome side of their minds and hearts. And that’s a good part of childhood, as we all know. It’s a wonderful part of childhood, and let’s hope it lives on even as we also hope that the children learn to be good decent members of a country and of a community. So it’s a balance.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. COLES: But that balance children remind us of, even as we try to be balanced parents, going back and forth and encouraging different aspects of human life in our children as we try to find that balance in ourselves.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Robert Coles is a retired child psychiatrist and Harvard professor and the author of over 70 books, including The Spiritual Life of Children. His latest books include House Calls with William Carlos Williams, M.D. and Minding the Store, an anthology of literary reflections on the business world.

In a recent production visit to Trinity Church on Wall Street, our producers discovered an archive of more than 13,000 letters and drawings by children that were posted on the walls and pews of Trinity’s chapel at what became Ground Zero after the twin towers fell. These messages of support to rescue workers and families illustrate Robert Cole’s stories about the witness and wisdom of children. We’ve scanned high-resolution images of some of them for you to view. See them online at speakingoffaith.org.

Also, download free MP3s of this produced program and my complete unedited conversation with Robert Coles. There are several ways to do this. You can subscribe to our weekly newsletter and our podcast and have it delivered directly to your computer, or you can download them on demand from our Web site.

And in our ongoing series, “Repossessing Virtue,” we’re posing questions to some of our past guests about the moral and spiritual impact of the economic present. Some of our most enlightening observations have come from you, our listeners, and we’ve recorded some of these stories of personal transformation and struggle. Give them a listen and add your insights on our blog, SOF Observed. Look for all these links on our homepage, speakingoffaith.org.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck, Shiraz Janjua, and Rob McGinley Myers, with help from Amara Hark-Weber and Nancy Rosenbaum. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with Web producer Andrew Dayton. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections