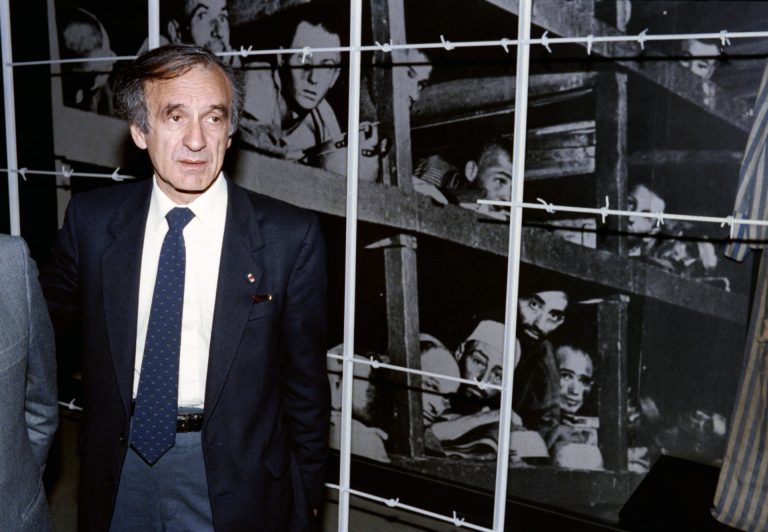

Elie Wiesel

The Tragedy of the Believer

A survivor of the Holocaust, in which he lost most of his family, Wiesel was a seminal chronicler of that event and its meaning. Wiesel shares some of his thoughts on modern-day Israel and Germany, his understanding of God, and his practice of prayer after the Holocaust.

Image by Sven Nackstrand/Agence France-Presse / Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Elie Wiesel was a writer, professor, political activist, and Holocaust survivor. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor and the Nobel Peace Prize, and was Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University.

Transcript

July 13, 2006

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, Elie Wiesel on the literary and religious journey that unfolded after Night, his seminal memoir of faith and childhood consumed by Holocaust. We’ll hear passages of his varied writings of the last 50 years. We’ll explore his thoughts on God and evil, youth in Jerusalem and Berlin, and prayer after the Holocaust.

MR. ELIE WIESEL: Some people who read my first book, Night, they were convinced that I broke with the faith and broke with God. Not at all. I never divorced God. It is because I believed in God that I was angry at God, and still am. The tragedy of the believer, it is deeper than the tragedy of the non-believer.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

I’m Krista Tippett. Elie Wiesel stands in the modern imagination as a towering moral figure. He’s known for his work on behalf of the Jewish people and also other peoples across the world who face suffering and persecution. At the same time, Wiesel is often cited as an intellectual symbol of reasonable religious despair. In his memoir, Night, which has recently landed on best-seller lists five decades after its publication, Elie Wiesel declared that he lost his faith forever at Auschwitz. This hour, we explore what that declaration meant and how it has evolved in Elie Wiesel’s life and his perspective on the world.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “The Tragedy of the Believer: An Intimate Conversation with Elie Wiesel.”

A Jew born in Romania, Elie Wiesel spent part of his childhood in the Nazi concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. There, his parents and his young sister died. After the war he made his way to Paris, where he became a journalist.

In 1958, at the age of 29, he published his memoir, Night. Until that time, the vast horror of the Holocaust had barely been given public words. Wiesel has said that Night is the text on which all of his later writing is just commentary. But that body of commentary has grown to more than 40 books, nonfiction, fiction, plays, and poetry. The act of writing itself is part of the way Elie Wiesel navigates the religious territory of life. He noted that connection in 2005 at New York’s 92nd Street Y where he has given an annual series of lectures on Jewish thought for four decades.

MR. WIESEL: (excerpt from lecture) Literature and prayer have much in common. Both take everyday words and give them meaning. Both appeal to what is most personal and most transcendent in a human being. Both are rooted in the most obscure and mysterious zone of our being, nourished by anguish and fervor. The writer and the worshipper both draw from one source, the source where sound becomes melody, and melody turns into language, which becomes offering. Both are as open as an open wound. Both live tense and privileged moments. If one may assume that man could not live without literature, which is not so sure, one may equally affirm that neither could he survive without prayer.

MS. TIPPETT: In recent years, Elie Wiesel has written a number of books with explicitly religious themes, drawing especially on the mystical Hasidic tradition. Wiesel’s grandfather taught him to love this way of faith in early childhood, before their world fell apart. Hasidism grew as a movement among European Jews in the 18th century, and it contains a playful and creative belief in the power of stories. Elie Wiesel likes to cite a passage of the Talmud that says, God created man because He loves stories. And as soon as we sat down to speak, even before we’d started to record, Elie Wiesel began to tell me a Hasidic legend. Our conversation began there.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I wanted to get to this later, but let’s talk about how you have — seem to have come to, or back to, a love for these Hasidic traditions and tales and stories. Is that something that…

MR. WIESEL: Never stopped.

MS. TIPPETT: It never stopped?

MR. WIESEL: No.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve written a great deal about it in the last sort of 20 years.

MR. WIESEL: I have written — yes, I have written some books.

MS. TIPPETT: And it was, you were really bred on that, weren’t you, in your childhood.

MR. WIESEL: To me, Hasidism is not simply a theory or a doctrine, not even a way of life, because it was my childhood. I go back to it has remained with me because my childhood accompanies me to this day. It is the child in me who is a Hasid, and I listen to the child in me.

MS. TIPPETT: But I do have an impression, and maybe this is wrong, but that that’s more part of your life and your thought in the last few decades. Is that not true?

MR. WIESEL: Not the Hasidic theory or the Hasidic doctrine or the Hasidic way of life changed. I changed. I changed, meaning not in depth, not in volume. Some people who read my first book, Night, they were convinced that I broke with the faith and broke with God. Not at all. I never divorced God. It is because I believed in God that I was angry at God, and still am. But my faith is tested, wounded, but it’s here. So whatever I say, it’s always from inside faith, even when I speak the way occasionally I do about the problems I had, questions I had. Within my traditions, you know, it is permitted to question God, even to take Him to task.

MS. TIPPETT: Quarrelling with God.

MR. WIESEL: Yeah, we may. It’s even more than that, you know. It is suing God. The expression is really “suing God.”

MS. TIPPETT: That’s the expression in the Hebrew?

MR. WIESEL: Hebrew, yeah. I sue God because in Hebrew, (speaking Hebrew), I bring him to rabbinic tribunal. And the arguments are all the arguments I take from the Bible and from his words. I mean, I take God’s words and say, since You said these words, how is it possible that other things or certain things have happened?

MS. TIPPETT: It’s because you take God so seriously that you ask.

MR. WIESEL: Yes, sure. André Malraux was a very great French author. He wrote La Condition Humaine, man’s fate, great author really, and he’s the one who said, the Jewish people were the only ones to take God’s words seriously, which means God spoke to everybody.

MS. TIPPETT: When did he write that?

MR. WIESEL: He wrote it in the fifties.

MS. TIPPETT: So after the Holocaust.

MR. WIESEL: After the Holocaust, yeah. But he never spoke about — he never wrote — I didn’t know him. I read his work. He never wrote about the Holocaust. In those times, the great writers all avoided the subject.

MS. TIPPETT: So as I was preparing to meet you, I looked through a number of your books again, some that I’ve read before, some that I hadn’t, and then I ended up going back to Night, which you can see has lost its cover a few years ago, which you have also said was the primary text, that everything else you’ve written and said is commentary on this. And, you know, this question that you just addressed of your loss of faith, I think comes especially from this famous passage.

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever.”

And I know that’s a passage that people often refer to when they think of your faith, and what I’d love to get into with you today is what happened after that? I mean, you’ve just given me a kind of an answer that it’s because you are a person of such faith that you had to keep asking these questions.

MR. WIESEL: What happened after is in the book. I went on praying. So I have said these terrible words, and I stand by every word I said. But afterwards, I went on praying. I described Rosh Hashanah, the Kaddish, everything. I went on praying.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. I remember once you also — you prayed for your safety or the safety of someone else.

MR. WIESEL: My father with me. At that time, it was my father. But I prayed. I mean, I knew the prayers by heart. I come from a very religious background so, of course, I knew these prayers well. But — we didn’t have prayer books, but I prayed. We all prayed. It’s extraordinary.

Later on I wrote a play called The Trial of God. In there, I bring these problems and these conflicts, these crises, to a different direction, but it’s always prayer. I love prayer.

MS. TIPPETT: And did you pray even questioning whether there was an entity to hear that prayer?

MR. WIESEL: I never doubted God’s existence. I have problems with God’s apparent absence, you know, the old questions of theology. And they are topical even today.

MS. TIPPETT: Elie Wiesel. Here’s a reading from his play The Trial of God. The play tells the story of Jewish survivors of a 16th-century pogrom, who imagine putting God on trial for the terrible things he allowed to happen to them. Speaking here is the character of Berish, an embittered innkeeper who assumes the role of prosecutor.

READER: Men and women are being beaten, tortured, and killed — how can one not be afraid of God? True, they are victims of men. But the killers kill in God’s name. Not all? True, but numbers are unimportant. Let one killer kill for God’s glory, and God is guilty. Every person who suffers or causes suffering, every woman who is raped, every child who is tormented implicates Him. What, you need more? A hundred or a thousand? Listen: Either He is responsible or He is not. If He is, let’s judge Him; if He is not, let Him stop judging us.

MS. TIPPETT: When I read you, looking for this idea of the nature of God, it seems to me, though, that you’ve done something quite profound. I mean, you are saying also that we have to take with absolute seriousness the idea that God is in everything, which is quite a dramatic — a statement with dramatic consequences.

MR. WIESEL: In saying that, I quote the mystical book, the Zohar, “God’s Splendor,” which is in Hebrew (speaking Hebrew). I mean, there is no place void of Him. And then, of course, the question: Since it is so, since God is God and God is everywhere, what about evil? What about suffering? Is He there too? These are heartbreaking questions to those who believe, but then, again, the tragedy of the believer, it is deeper than the tragedy of the nonbeliever.

MS. TIPPETT: Say some more, what you mean by that.

MR. WIESEL: I’m speaking of after the war, after the experiences our generation went through. Remember, I belong to a generation that has not learned the way to live, but learned that there are a thousand ways of dying. And as a result, we ask all the questions first. What happened to humanity? What happened to the human race? What happened to human nature? What happened to democracy? What happened to our friends in the world, Roosevelt and — and all these good questions. At the end of the questions, we cannot avoid saying, and where was He or where are you?

MS. TIPPETT: Where was God?

MR. WIESEL: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: Um-hum. Although I think the way that question is asked, let’s move to America in this time, in these last few years, let’s say September 11th and the way Americans woke up to violence. And the question, where was God or a discussion of evil was something that was outside, right? The evil was something that was completely removed from the character of God, but you’re actually saying that we can’t do that.

MR. WIESEL: I’m not saying that God, God forbid, is evil. I’m asking a question: Since God is God and God is everywhere, does it mean that he is also in evil? That He is in suffering, I accept. That He is with the sufferer, I accept. Again, that is part of the Jewish tradition, too. When God sent the people of Israel into exile, He accompanied them into exile. That’s a mystical concept which — again, tremendous beauty and emotion. But about evil, I have to swallow very hard before asking even the question. But one must ask the question.

So 9/11, of course, like you, like everybody else, I was shocked, I was glued — I would not like television, I like words, not pictures, but I was glued to television. Couldn’t understand. But at that time, in truth, I didn’t think theologically. I simply think humanly. What is it about 19 young men who decide to do what they have done? What is it about? And I studied the history of terrorism, the psychology of — I really studied because my second book, my first novel after Night, is about — actually about terrorism. I wanted to understand it and I said, what — my God, what is happening to this world?

MS. TIPPETT: Elie Wiesel set his second book, Dawn, in immediate post-World War II Palestine, which was occupied by British forces. The story’s protagonist, Elisha, is a young Jew just released from the concentration camp, Buchenwald. In Paris, he is recruited by a Jewish terrorist movement to drive the British military out of Palestine and hasten the birth of a Jewish nation. In this passage, the movement’s leader, Gad, describes his theology of terrorism.

READER: The commandment “Thou shalt not kill” was given from the summit of one of the mountains here in Palestine, and we were the only ones to obey it. But that’s all over. We must be like everybody else. Murder will be not our profession, but our duty. In the days and weeks and months to come, you will have only one purpose: to kill those who have made us killers. We shall kill in order that once more we may be men.

MS. TIPPETT: A passage from Elie Wiesel’s novel Dawn. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today we’re in conversation with Elie Wiesel about his faith after the Holocaust, and his understanding of the nature of God then and now.

In his work, Wiesel often writes about the creation of the state of Israel as one of the great events of his lifetime. In a 1995 memoir, he described the wonder of surviving the Holocaust and visiting the Jewish state for the first time in this way, “I belonged to the community of night, the kingdom of the dead, and henceforth I would also belong to the wondrous, exhilarating community of the eternal city of David.”

I asked Elie Wiesel how he experiences what is happening in Israel today.

MR. WIESEL: Israel, I read and I see the pictures in the papers. I read and I weep, and I don’t weep usually. I read and I weep. My God, the city that was destined to be the city of peace, and look at the bloodshed, the cruelty, the suffering, the agony. And then we say, it must stop. My God, it must stop. So what else can we do? We must do something, anything we can, to stop the absurd direction of hatred. We must.

MS. TIPPETT: So I want to ask you how you come at this question about where God is in the violence in Israel. I mean, if God is everywhere, can God, at one and the same time, be in an Israeli’s love for that land and every Jew’s love for that land, and also in these acts of violence, in a suicide bomber?

MR. WIESEL: What makes it worse is those who kill, kill, so to speak, in the name of God.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. WIESEL: They didn’t ask God. God didn’t tell them to kill, but they say, we do it in the name of God. Oh, I don’t like to say negative things about other people but, really, all these people say that they are martyrs. We Jews, and Christians, too, we know something about martyrdom. A martyr is someone who is ready to die for his or her faith, not to kill for his or her faith. And there it’s a perversion of every concept of faith, what they are doing to kill children. Why? So rather than here to turn to God, I rather turn to those who invoke His name in vain, just to kill, and kill, and kill, and then be killed. A cult of death; for them death is God.

MS. TIPPETT: So for you, the results of those actions is some indication of an absence of God?

MR. WIESEL: We have a certain concept — it’s from the Bible actually, and we call it the eclipse of God, that God at times is hiding His face. I have often — whenever something terrible happens, it’s not because God wanted it. God didn’t want to see it. So it’s not absence. It is the turning His face away. What is a tragedy? God’s turning the face away and therefore comes the tragedy, or the other way around, first the tragedy and God doesn’t want to see it so He turns away? But when people do terrible things to one another, first we must ask them, why are you doing it? And then we may, at the end, if we have the answer, say, and God, why do You allow these things to happen? Otherwise it’s too easy, really, to say, God, why didn’t You intervene? Well, God gives us the world, which He wanted — not perfect, but beautiful — and what are we doing to it?

MS. TIPPETT: Elie Wiesel. Here’s a portion of an essay in the form of an open letter to a young Palestinian, which he published in 1978.

READER: It is the human aspect of your problem that I find most painful. Its dialectical aspect leaves me indifferent. Its ethical side troubles me. I am irritated by your threats but overwhelmed by your suffering. I am more sensitive to that than you imagine. The people of my generation cannot be otherwise. They have seen too many men tortured, uprooted, to turn away from other people’s grief. It concerns us and it affects us. Your behavior is conditioned by Arab suffering and mine by Jewish suffering. These two sufferings should unite us, but instead they divide us.

MR. WIESEL: I could write this letter today. It is so topical. But I say, in truth, I would feel all the sympathy in the world for the young Palestinians who want to live in peace and to have a state, and peace — I almost quote myself — is not a something, a gift that God is giving us. It’s a gift that we give to each other. So if they would stop terrorism, I would do whatever I can to help them, but I cannot help terrorists. It is something which I oppose with all my heart. It is this terrorism rooted in fanaticism. We are dealing now — in the Middle East we are dealing with a situation in which everything, everything that goes bad has happened there. It’s politics. It’s economy. It’s poverty. It’s despair. It’s psychology and psychiatry and science, everything there. It’s a combination and, of course, religion. So all this together, but it could have worked.

I was in Washington on September 13th, 1993, and I was in the White House. And I watched Yitzhak Rabin, who was a very close friend of mine, and Arafat shake hands, and that day was a blessing. I saw it as a day of blessings. I felt, well, it is finished; now we can start building hope. But look where we are.

MS. TIPPETT: Does that make you despair?

MR. WIESEL: Often. But I have no right to. If I am alone, I would despair. But there are young people in the world and I don’t think that I survived to give them despair.

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s an excerpt from Elie Wiesel’s Nobel lecture of December 11th, 1986, read by Rabbi Harold Schulweis.

RABBI HAROLD SCHULWEIS: And here we come back to memory. We must remember the suffering of my people, as we must remember that of the Ethiopians, the Cambodians, the boat people, Palestinians, the Mesquite Indians, the Argentinean desaparecidos — the list seems endless.

Let us remember Job who, having lost everything — his children, his friends, his possessions, and even his argument with God — still found the strength to begin again, to rebuild his life. Job was determined not to repudiate the creation, however imperfect, that God had entrusted to him. Job, our ancestor. Job, our contemporary. His ordeal concerns all humanity. Did he ever lose his faith? If so, he rediscovered it within his rebellion. He demonstrated that faith is essential to rebellion, and that hope is possible beyond despair. The source of his hope was memory, as it must be ours. Because I remember, I despair. Because I remember, I have the duty to reject despair. I remember the killers, I remember the victims, even as I struggle to invent a thousand and one reasons to hope. Mankind must remember that peace is not God’s gift to His creatures, it is our gift to each other.

MS. TIPPETT: From Elie Wiesel’s 1986 Nobel lecture. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more conversation with Elie Wiesel. We’ll hear his thoughts on the meaning of Jerusalem, on forgiveness and prayer.

At speakingoffaith.org, learn more about the readings, references, and music you’ve just heard. Listen to this program again. Download an MP3 to your desktop or subscribe to our free weekly podcast. Listen when you want, wherever you want. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Tragedy of the Believer,” an intimate conversation about religious life beyond the Holocaust with Elie Wiesel. He’s received the Congressional Medal of Honor and the Nobel Peace Prize. He’s renowned for his efforts on behalf of the Jewish people and also other peoples across the world who face suffering and persecution. In recent months, Elie Wiesel has spoken out against human rights abuses in Sudan, and he has joined global leaders in urging the U.S. to abolish torture without exceptions. We’re speaking now about his love for Israel and his grief that a peace that seemed so close in his lifetime, has erupted into new cycles of conflict and bloodshed.

MS. TIPPETT: And you know, when people in this country watch that conflict, they watch the Israelis seem to be as much a part of that cycle of violence as the Palestinians. And I don’t know, how do you respond to that?

MR. WIESEL: Look, I am a Jew. With my past and with my upbringing, I have, of course, a passion and love for Israel, the people of Israel and Israel. But it’s not limited. When I got the Nobel Prize, I said it in my speech there, I said, I hope you don’t give it to me for the wrong reasons. My priorities are Jewish priorities, Jewish fears, Jewish hopes, Jewish struggles, but they are not exclusive. That’s why I try to be involved in every cause possible dealing with human rights. But you cannot give in to terror. No country can give in to terror. You cannot. You must not. You betray the mission that has been entrusted unto you by those who voted you into power. You have no right to do that. So how can I therefore say — I said I cannot — I say, Yes, I support, I believe, yes, there should be a Palestinian state, absolutely, but not instead of Israel, but alongside Israel.

MS. TIPPETT: And then I think one looks at the state in which the Palestinians live, and it seems to me that Jews in Israel live with these texts which say different things which are hard to bring together sometimes. I mean, the commitment to the land and then also the commandment to care for the widow and the orphan, right? I mean…

MR. WIESEL: Sure. I can quote to you beautiful things, naturally, what we say about slavery, for instance. One of the most beautiful thing about our attitude to slaves, it was written 3,500 years ago, after all, after the Ten Commandments. The first law, the first after the Ten Commandments, is you shall have no slaves. Not, don’t be slaves. You cannot own slaves. And then later on, if a slave escapes, you cannot give him back to his owner.

The attitude — and we are talking about a people that a few years earlier had been slaves in Egypt. So there are great things actually and, of course, the most important one of all, to me, by the way, is thou shall not stand idly by. Always. So yes, when I see what is happening to the Palestinians, it hurts. Naturally, it hurts.

MS. TIPPETT: I feel that it’s almost impossible for Americans to really have a sense — maybe not for American Jews, but for other Americans to have a sense of the spiritual connection to that land. And you write a lot about how you experienced Israel growing as a state, coming out of your experience of the Holocaust. I mean, would you describe what your bond is to that place, what it has to do with your soul as a Jew? Can you put that into words?

MR. WIESEL: I wrote about it a lot because I prayed a lot. My first prayer was about Jerusalem. The first lullaby my mother used to sing me was about Jerusalem. I knew Jerusalem, the word Jerusalem, before I knew the name of my hometown. I know the streets of Jerusalem, the houses of Jerusalem, before I was there. Because somehow Jerusalem was the center of our dream, the center of our aspirations, the center of our hope. It’s Jerusalem, the city of peace. The first male was David, King David of Jerusalem. And when I came to Jerusalem for the first time, I had the feeling it wasn’t the first time, I’d been there before. And nevertheless, each time I go to Jerusalem, I have the feeling it’s the first time. It’s the only city in the world that I feel that way.

I wrote — after the Six Day War, I wrote the novel called A Beggar in Jerusalem because I felt we all come there as beggars, maybe, to receive. We want to receive. And we receive a lot. And all I used to do there was immediately after the liberation of the old city, I would go there and I wrote my — with my lips. In the evening, I would go to the hotel and write down what I have written with my lips. And then at that time, of course, it was so special. At the same time, I write in my novel, and as I walked in the old city and I saw Arab children and because — they realized that I was Jewish simply because I was at the wall praying, so I inspired fear in them, and that hurt me more than I can say, that I should inspire fear in children. Well, what else can one do today but tell the story and hope that the story itself will become a prayer.

MS. TIPPETT: Elie Wiesel. This is a passage from his 1970 novel, A Beggar in Jerusalem.

READER: Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, the storyteller of Hasidism, liked to say that no matter where he walked, his steps turned toward Jerusalem. As for me, I discovered it in the sacred word. Without taking a single step. I saw it then, as I see it now.

Here is the Valley of Jehoshaphat, where one day the nations will be judged. The Mount of Olives, where one day death will be vanquished. The citadel, the fortress of David, with its small turrets and golden domes where suns shatter and disappear. The Gate of Mercy, heavily bolted. Let anyone other than the Messiah try to pass and the earth will shake to its foundations. And higher than the surrounding mountains of Moab and Judea, here is Mount Moriah, which since the beginning of time has lured man in quest of faith and sacrifice.

It was here that he first opened his eyes and saw the world that henceforth he would share with death. It was here that, that maddened by loneliness, he began speaking to his Creator and then to himself. It was here that his two sons, our forefathers, discovered that which links innocence to murder and fervor to malediction. It was here that the first believer erected an altar on which to make an offering of both his past and his future. It was here, with the building of the Temple, that man proved himself worthy of sanctifying space as God had sanctified time.

MS. TIPPETT: From A Beggar in Jerusalem by Elie Wiesel. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, conversation with Elie Wiesel on what he calls the tragedy of the believer.

MS. TIPPETT: In recent years, we’ve had an example of a country, South Africa, in which there was an evil and horrible regime, but they had this process of truth and reconciliation, of telling the story, telling their collective story and trying, I think, to live out of that experience differently as a culture. Now, I spent some years in Germany as a journalist and I couldn’t help but wonder, as I watched what was happening in South Africa, how it might have been different if there had been some process like that. I wonder if you, as someone who experienced those camps and the dark side of that, have reflected on something like that. Or what is your relationship to Germany now, is another question.

MR. WIESEL: First South Africa.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. WIESEL: I went to South Africa in 1975, going around literally from town to town, fighting apartheid. Why? Because I felt we have no right not to interfere, not to intervene. Couldn’t humiliate an entire people because of their race, right? Then Mandela came — the first trip he took actually when he left jail — to a conference I organized in Oslo, Anatomy of Hate. I organized people from all over the world, both sides. And then I came and I invited a minister of the apartheid government. But I checked; he didn’t have blood on his hands. At one point — I had heads of states and Nobel laureates. At one point, the young minister of the apartheid government turned to Mandela and said, Nelson, I grew up in apartheid. My dream now is to attend its funeral. And it was so beautiful that I put them together, and that was the beginning of the end of apartheid. That’s how it began.

Germany, you were there, and I was there once visiting. I am asked occasionally, you know, do you forgive? Who am I to forgive? I am not God. I don’t believe in collective guilt.

MS. TIPPETT: I met you there. We talked about it. It was January 20th, 1985. Now, I have a recollection it was one of the first…

MR. WIESEL: First time in Berlin.

MS. TIPPETT: First time you’d been in Berlin. You met with a group of young Germans, and I have never forgotten what you said when you came out. I was there with another New York Times correspondent, and you said, “I had never before considered that it could be as painful to be the children of those who ran the camps as to be the child of those who died in them.”

MR. WIESEL: Because I have students from Germany and you cannot imagine the affection I have for them, the empathy I have for them. I want to help them. They need help. One of them said to me, even in Berlin then, said, you know, “I just discovered a few weeks ago that …” — he discovered that his father was an S.S. officer. He said, “What should I do? You know, what Hitler has done. He destroyed so many lives that had not been born yet. His people.”

MS. TIPPETT: How did you respond to that student?

MR. WIESEL: Well, you can imagine. I took him aside and we spoke, and we spoke, and we spoke. And I simply said, “Look, he’s your father. Talk first. First let him talk to you, and you talk to him. And then you decide what to do. I understand. Absolutely, I understand.”

I went back to Berlin for the last time in the year 2000, January 27th. The Bundestag of the Parliament came to Berlin for the first time. They had a session, the Parliament, in the Reichstag in Berlin, and they invited me to speak. And I came. 27th of January. At the end of my speech, I turned to the president, who was there, and the entire government and diplomatic corp. I said, “Mr. President, why not ask the Jewish people for forgiveness? I’m not sure the Jewish people can accept, but why not ask?” A week later, he went to Israel, to Jerusalem. He went to the Parliament and he asked for forgiveness.

MS. TIPPETT: That trip was a result of your speech.

MR. WIESEL: I think so, yeah, so I felt good.

MS. TIPPETT: I don’t know, is “forgiveness” a big enough word or a good enough for this?

MR. WIESEL: No, I cannot — no, I cannot forgive.

MS. TIPPETT: You said you can’t forgive. So if you can’t forgive, what can you do? What is the endeavor, the holy endeavor?

MR. WIESEL: I won’t say this is, this is the — I must first of all to tell the truth and to sensitize other people not to do the same thing. We aren’t here to forgive. We are — the Jewish — in the Jewish faith, on the eve of Yom Kippur, which is the holiest day of the year, and we plead, we call for forgiveness, and God forgives, I hope. But one thing He does not forgive: the evil I have done to other fellow human beings. Only they can forgive. If I do something bad to you, I cannot ask God to forgive me. You must forgive.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s much harder, much more exacting. I wondered if I could ask you to read a prayer. Is it here? Yeah. This is a prayer that I found in your book One Generation After. You talked a lot in Night — and we talked about this already — about struggling with prayer, to be able to pray or not, or what it meant. And I think this was a prayer that you wrote in a diary.

MR. WIESEL: I agree, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And I wondered if you would read that to me and just talk to me then — we have to finish but about how you began to pray again and how you pray you differently now because of the life you’ve lived.

MR. WIESEL: “I no longer ask You for either happiness or paradise; all I ask of You is to listen and let me be aware and worthy of Your listening. I no longer ask You to resolve my questions, only to receive them and make them part of You. I no longer ask You for either rest or wisdom, I only ask You not to close me to gratitude, be it of the most trivial kind, or to surprise and friendship. Love? Love is not Yours to give.

As for my enemies, I do not ask You to punish them or even to enlighten them; I only ask You not to lend them Your mask and Your powers. If You must relinquish one or the other, give them Your powers, but not Your countenance.

They are modest, my prayers, and humble. I ask You what I might ask a stranger met by chance at twilight in a barren land. I ask You, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to enable me to pronounce these words without betraying the child that transmitted them to me. God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, enable me to forgive You and enable the child I once was to forgive me too. I no longer ask You for the life of that child, nor even for his faith. I only implore You to listen to him and act in such a way that You and I can listen to him together.”

MS. TIPPETT: I’m wanting to ask you if, in this journey from being a person who felt that his — or who would say that your faith was gone forever, were there any dramatic moments or turning points where you couldn’t make that statement anymore?

MR. WIESEL: I couldn’t make it ten minutes later. At that moment, I made it. And because it was there, I had to make it. But as I said earlier, then I went back to prayer. Again, remember that — what is prayer? You take words, everyday words, and all of a sudden they became holy. Why? Because there is something that separates one word from another and then you try to fill the vacuum. With what? With whom? With what memory? With what aspiration? So when words bring you closer to the prisoner in his cell, to the patient who is dying on his bed alone, to the starving child, then it’s a prayer.

MS. TIPPETT: All right. Elie Wiesel, thank you so much.

MS. TIPPETT: Elie Wiesel’s most recent book is a novel, The Time of the Uprooted. The latest edition of Night is a new translation from the original French by his wife, Marion. At speakingoffaith.org, read the complete text of the prayer recited by Elie Wiesel. Listen to this program again and hear others in our archives. Download an mp3 to your desktop or subscribe to our podcast, and sign up for our e-mail newsletter, which brings my journal on each week’s topic straight to your desktop. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and editor Ken Hom. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss. Special thanks this week to Rabbi Harold Schulweis, the senior rabbi at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, California, for the readings in this program. Thanks also to New York’s 92nd Street Y for the audio of Elie Wiesel’s 2005 lecture. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. The executive producer is Bill Buzenberg. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections