Anita Desai + Andrew Robinson

The Modern Resonance of Rabindranath Tagore

He bestowed the title “Mahatma” on Gandhi. He debated the deepest nature of reality with Einstein. He was championed by Yeats and Pound to become the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. Rabindranath Tagore was a polymath — a writer and a painter, a philosopher and a musician, and a social innovator — but much of his poetry and prose is virtually untranslatable (or inaccessibly translated) for modern minds. We pull back the “dusty veils” that have hidden his memory from history.

Guests

Anita Desai is an Indian novelist of Bengali descent. Her novels include Clear Light of Day, The Village by the Sea, and Fasting, Feasting.

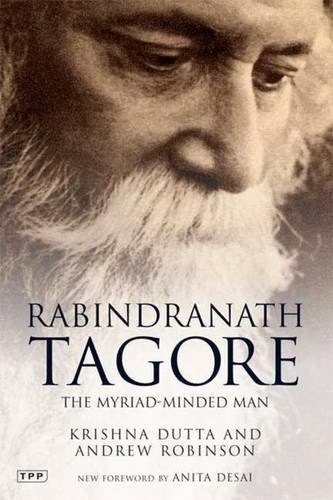

Andrew Robinson is a biographer and writer. He is the co-author of Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man and author of The Art of Rabindranath Tagore.

Transcript

August 6, 2014

ANDREW ROBINSON: Tagore said, “I’m not a philosopher.” I mean, people regarded him as a philosopher, but he rejected that label. So I think his whole view of life was profoundly influenced by the fact that he was an artist.

ANITA DESAI: There seems to be no aspect of life There seems to be practically no aspect of life that he didn’t try to touch, to alter, to somehow bring around to his ideal of how things should be.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: That’s the writer Anita Desai, on Rabindranath Tagore. This hour, we pull back what Anita Desai calls the dusty veils that have hidden his memory from history. This is the man who bestowed the title “Mahatma” on Gandhi. Tagore was championed by Yeats and Pound to become the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. The Indian and Bangladeshi national anthems today are Tagore’s compositions. And you may have seen a picture of him without knowing it — a famous photo of Tagore in long gray beard and flowing robe — sitting with Einstein in a suit and tie in Einstein’s Berlin home, where they debated the deepest nature of reality.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[Music: “Tumi Dhanya Dhanya Hey” by Sumitra Roy & Rabindranath Tagore]

MS. TIPPETT: Rabindranath Tagore was born on May 5, 1861 in Calcutta. His wealthy Bengali family also owned vast estates in what is now Bangladesh. As an adult, he managed these estates and conducted social and educational experiments there, some of which have remnants in India today.

Later, we’ll draw out Anita Desai on Tagore as a figure in her Bengali heritage and for her as a modern Indian writer. But first, British author Andrew Robinson. He co-authored a biography of Tagore called The Myriad-Minded Man.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, as we begin, I’d love to hear how you first discovered Tagore. What was your earliest awareness of him? What was the context in which that happened?

MR. ROBINSON: That was through the films of Satyajit Ray…

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, okay.

MR. ROBINSON: Who was a student at Tagore’s University, and Ray made several lovely films, some of them masterpieces based on Tagore’s short stories and a novel. And he used a lot of Tagore’s music. So I saw those when I was quite young, and then I wrote a biography of Ray and, of course, there was some of Tagore in there too.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a line in your biography, The Myriad-Minded Man. “He is found everywhere in Bengali life, and yet he is lost.”

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, yes. Well, he is. He is found everywhere particularly in his songs which every single Bengali knows a bit about and many of them can sing them. But I think in many ways the complexity of the man is lost. He was much more than just a simple poet with a simple message. He was a complex figure, like Gandhi in that respect.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. Although, I don’t know, we’re going to obviously flesh this out, but I wonder also if it is his very complexity that has made him hard to make him just a symbol of something. You know? Because it seems like he did so many things. I mean, this myriad-minded man is a good description, and he saw ambiguity in everything in such an interesting way. He was always evolving, it seems, all the way through his 80-plus years.

MR. ROBINSON: Yes. And he always said in the years after he won the Nobel Prize that, you know, if I’d stuck to doing the kind of poetry that first won me that prize — which W. B. Yeats so admired, the poetry called “Gitanjali,”song offerings and some other collections — Tagore knew that, if he’d stuck to doing this rather straightforwardly semi-mystical love poetry with a strong sense of the divine, he would have been a much — he’d probably be a much more famous man now than he actually is because he did so many other things. He got bored, in a sense, and frustrated, I think, with the image that had been created at that time in his life in 1913 around the time of the First World War. And he wanted to get away from it in later life.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, there’s something in Tagore’s personal trajectory that actually reminded me of the story of the Buddha. The prince enclosed, you know, living this life of containment and luxury who one day ventures out and sees all the suffering and the poverty and his vision is changed. And there’s a bit of that in Tagore’s story, I feel, but, I mean, you know this story better than I do.

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, there is a bit, you’re right. I mean, more in his father’s case because his father was the son of an extremely wealthy man, grandfather of Rabindranath, known as Prince Dwarkanath Tagore. He wasn’t actually a prince, but he was a merchant prince, India’s first industrial entrepreneur, I think you could say, an incredible figure in his own right, but not at all a spiritual man, but also not a lackey of the East India Company or the British government.

He was an independent man and he handed wealth down to his son and the son — the father of Rabindranath, that is, the Maharshi, as he was known, the Maharishi, so to speak — he rejected that as a young man, and so Tagore, the grandson, I think, inherited both traditions. The luxury-loving tradition of his grandfather and the austerity of his father. In a sense, they ran side by side throughout Tagore’s life.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I think there’s a sense — you used this phrase a minute ago when you said if he’d just continued writing those semi-mystical poetry that had won him the Nobel Prize for literature, he might have stayed more famous. He was almost glorified by people like Yeats and Pound, in a way, imagining a spirituality in him that Britain had lost or that was not accessible to them.

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, and not just Yeats and Pound. I mean, there was a whole sense that Tagore looked like Christ. I mean, many people said this.

MS. TIPPETT: Literally looked like…

MR. ROBINSON: Yes. Many people said that. At the passion play in Oberammergau, people said, “How like our prophet”. It was a German audience. And Darwin’s granddaughter, I think, said, “I could now understand this powerful and gentle Christ, which I never could before,” after seeing Tagore. So there was a very strong feeling that he represented moral goodness in addition to being a poet. And I think the First World War did have an effect on his reputation, which increased it and then, in the 20s, it to some extent collapsed…

MS. TIPPETT: Because there was kind of this spiritual despair and vacuum of those years?

MR. ROBINSON: Yes. Wilfred Owen took Tagore’s poetry to the trenches…

MS. TIPPETT: Right, of World War One.

MR. ROBINSON: After Owen was killed, his pocketbook was sent back to his mother and there were some lines from Tagore in it. And she then wrote to Tagore when he visited London in 1920 and said, “I would be very grateful if you could tell me where these lines come from.” And those lines are to be found in the faculty library in Oxford University. You can see it still.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you remember what they are? Or anything?

MR. ROBINSON: Uh, “When I go from hence, let this be my surpassing work” — I haven’t got this quite right.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, that’s okay. What was it expressing that is there in Tagore’s thinking?

MR. ROBINSON: Uh, I think it’s expressing what he said was the great theme of his work, which was the finite in the infinite. All his work he felt was expressing that idea, and that’s part of certain strands of Indian philosophy too.

MS. TIPPETT: Is that connected to another idea that’s there, that spirituality — and I don’t know if he would have used that word — leads humanity from partiality to fullness. The finite and the infinite, partiality and fullness, the real and the unreal is another thing he talked about.

MR. ROBINSON: Yes. He goes into this with Einstein, doesn’t he, in a certain amount when they had a conversation with that rather wonderful headline in New York, “A mathematician and the mystic plumb the truth” [laughs].

MS. TIPPETT: That was in The New York Times, wasn’t it?

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, yes. I liked that.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s talk about that conversation he had with Einstein, because you’ve written about that. You know, you were talking a minute ago about how he looked and, you know, he always, even after having won the Nobel Prize and being knighted — he had to relinquish that, but being knighted, he was very striking, stunning, longhaired, bearded, and many have of seen a photograph. There’s a photograph that’s often shown when people look at photos of Einstein, life of Einstein and Tagore. But many people don’t — Tagore hasn’t come down in memory for even the way Gandhi — certainly the way Gandhi or Einstein came down in memory. So he’s this figure out there…

MR. ROBINSON: Although you do find Tagore referred to the Encyclopedia Britannica actually on Einstein. You do find that, in fact.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, the conversation between them is quoted there because it’s so kind of precise, the difference between the two of them.

MS. TIPPETT: Between the two of them, right. Who was it — Isaiah Berlin said, “It was a complete non-meeting of minds.” [laughs]

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, that time he wrote that to me. And Isaiah Berlin knew of it because he’d attended Tagore’s lectures in Oxford in 1930 and he knew Einstein, so he knew both sides to some extent, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: But non-meeting of minds it may have been, but it’s a fascinating dialog. And it remains, I think, fascinating today, reading it today. It’s very interesting that Einstein is compelled to say at the end of this long discourse about truth and beauty and reality, “Then I am more religious than you are.” [laughs]

MR. ROBINSON: That’s right [laughs]. I am more religious than you are.

MS. TIPPETT: So take us inside. What happened there that could lead Einstein whose real religion, whose deep religion — he had, as you said, a cosmic spiritual sensibility, but his real religion was a deep reverence for science and for the laws of physics.

MR. ROBINSON: I think that it’s true to say that, in 1930 when Einstein was arguing with Nils Bohr about quantum theory and God does not play dice and the whole concept of uncertainty. The uncertainty relations in the atomic world, I think Einstein was quite fired up with this very, very strong belief in the independence of truth from the human world. The world is something out there independent of human beings.

And this is where he really — he and Tagore just could not see eye to eye because Tagore said, “No, no. The scientific world is still that of human beings. It’s still a human viewpoint. How else do we perceive truth except through our minds?” And Tagore had a sense that science was part of the human mind and indeed the cosmic mind. He believed in that. And that there was no truth that was independently existing of human beings.

MR. ROBINSON: That’s what he says and, of course, Einstein says, “But what about the table in this room? Even if we weren’t here, that table would still exist.” And Tagore’s actually even unable to accept that. He said, “Yes, it would still exist, but we would perceive it through the universal mind even if not through our individual minds.”

[Music: “Bushi Oi Sudure” by Various Artists]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today exploring the life and modern legacy of the Bengali writer, musician and painter, Rabindranath Tagore. I’m speaking with one of his biographers, Andrew Robinson.

MS. TIPPETT: So this is actually a quote from an edited version of an article you wrote about the mathematician and the mystic, the meeting between Einstein and Tagore. You know, you said, “Einstein writes this in 1930. If the moon in the act of completing its eternal way around the earth were gifted with self-consciousness, it would feel thoroughly convinced that it was traveling its way of its own accord on the strength of a resolution taken once for all.” And his point is that we — and this gets into free will, right? And that we also do what we do with self-consciousness believing that we have some kind of choice in the matter or some kind of integrity of action. But Tagore was saying — and you correct me if I’m getting this wrong — the fact that we perceive that table [laughs], that there’s a sense in which that table only has a reality in human perception, that you can’t write that off, that that is a form of reality and of truth, and that perhaps — didn’t he say — sorry. That science also takes place in the human mind.

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, he does, and he’s in a sense more in line with today’s thinking than Einstein was at that point, because of this current obsession with consciousness really, Tagore is saying that consciousness has created the universe. I think that’s what he’s really saying underneath it.

You know, I don’t want to go too far down this road, because I think Tagore himself had a — disagreement with himself when there was a terrible earthquake in 1934 in India and Gandhi made a statement to the effect that the earthquake is due to the sin of untouchability in India. I mean, he openly said that and he defended it. He defended that point of view very movingly. I think wrongly, but he did. And Nehru said, “Nothing more opposed to the scientific outlook is hard to imagine.” And he was very shocked. And Tagore agreed with Nehru on that occasion. He said that we may depend on it, however bigoted we may be, however great our inequity, but we cannot bring down the structure of creation.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And he was as opposed to untouchability as Gandhi, right?

MR. ROBINSON: Yes. I think almost as much, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Okay. But he said physical events have physical causes. I mean, here are some lines from “Sadhana”? The “Sadhana”?

MR. ROBINSON: “Sadhana”, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: When did he write that?

MR. ROBINSON: That was in the teens of the last century.

MS. TIPPETT: So, early, early on.

MR. ROBINSON: About 1913, I think, from memory, mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, so it seems to me that, yes, there’s that contradiction. He is trying to posit a capacity of humanity, whether you call it spirituality or consciousness that has its own force, right? I mean, so here are a couple of passages that struck me.

“The man of science knows in one aspect that the world is not merely what it appears to be to our senses.” That’s what we were saying a minute ago. “He knows that earth and water are really the play of forces that manifest themselves to us as earth and water, how we can but partially apprehend. Likewise, the man who has his spiritual eyes open knows that the ultimate truth about earth and water lies in our apprehension of the eternal will, which works in time and takes shape in the forces we realize under those aspects. This is not mere knowledge, as science is, but is a perception of the soul by the soul. This does not lead us to power as knowledge does, but it gives us joy which is the product of the union of kindred things.” That’s very, very provocative, isn’t it? He’s acknowledging that there is something — there are spiritual eyes and there are some kinds of ultimate truths, right?

MR. ROBINSON: Tagore said, “I’m not a philosopher.” I mean, people regarded him as a philosopher, but he rejected that label. So I think his whole view of life was incredibly, profoundly influenced by the fact that he was an artist. And art, poetry and many other things, music, of course, and painting, were what he — gave him the strongest sense of joy in his life. And he felt that the artist perceived the world probably differently from the majority of other people.

MS. TIPPETT: And that word joy, so central to him, right?

MR. ROBINSON: It is, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, this last line of the thing I read a moment ago, you know, “There’s knowledge that leads to power and there’s apprehension which leads to joy.

MR. ROBINSON: I think that, in the end, Tagore said that the joy matters more to him at least than the logical understanding or the idea that truth was independent of his perception. I mean, he didn’t really accept that because his whole life was artistic.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. There are these lines I love, I mean, essentially three lines, a little three lines of poetry. “I am a poet, I do not debate. I look at the world in its wholeness.”MR. ROBINSON: Yes, that’s a good one. I just wanted to mention another one actually which is a favorite of mine, an epigram of his. “The worm thinks it strange and foolish that man does not eat his books.”

MS. TIPPETT: I love that [laughs].

MR. ROBINSON: That quite goes to the heart of a lot of Tagore, I think.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. So tell me some more. I do sense that for you, Tagore’s painting becomes just as interesting as anything else he ever did. And, you know, it’s hard to talk about painting, it’s hard to talk about painting on radio.

MR. ROBINSON: It’s probably worth saying, yes, how he started, though. He started by elaborating his manuscripts that he had crossed out. He’d made corrections on his manuscripts. He would cross things out and then he felt they looked ugly, so he started making patterns with them with his pen and the patterns eventually grew into fully-fledged paintings and then he took up the brush. He still used the pen, but he took out the brush and started creating independent paintings. And then he started painting in earnest for the last decade of his life until 1941. And nowadays, his paintings are very sought after in India and worldwide and they’re quite difficult to buy.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I’m sure we’ll be able to put some of those images up on our website, because I’m just longing to actually have them in front of me as I’m hearing you talk about them. It’s very interesting, though, that his painting grew somehow organically from his working with words.

MR. ROBINSON: And may I say that they’re not — the reason I find them exciting and also many critics do, whether Indian or non-Indian, is they’re not predictably Indian. And that whole school of oriental art was rejected utterly by Rabindranath Tagore in his 60s. He said, “I’m going to paint from my mind. I’m going to paint from my imagination. I’m going to paint from my dream world.” And they’re almost all figurative. A few are totally abstract, but mostly they’re portraits or weird creatures that existed in his mind.

They’re so unexpected, you know? You just would never think that Tagore would have created these, the man who wrote “Gitanjali” and all those wonderful short stories so realistic about village life and town life and politics in India and so on. None of that is present in the paintings really. I mean, you get a sense of a man who’s not all at ease with himself and certainly not — I mean, he’s got demons, you know, and the demons are sometimes illustrated in the paintings.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. Well, I think every mystic has demons, but they don’t all put them on paper to exhibit to the world [laughs].

MR. ROBINSON: I’m sure you’re right.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s this thing that he’s said to have said on his — no, that he wrote in 1941 which, I believe, was near the end of his life. “As I look around, I see the crumbling ruins of civilization like a vast heap of futility.” And as you say, he was very outspoken about all the way through, you know, his life that things that were wrong. But then he concluded, “Yet I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in man.”

MR. ROBINSON: Hmm. And I think that’s very important. I think he didn’t. Tagore didn’t commit that grievous sin of losing faith in man. I mean, right to the end, the paintings show it, incidentally. But he…

MS. TIPPETT: How did the paintings show it?

MR. ROBINSON: Well, as light and joy and freedom in the paintings. And the people are the portraits often of very troubled people, I think, but you feel the painter’s empathy with them. I think he didn’t turn his back on human beings and take refuge in abstract art or the natural world. He’s always interested in human beings right to the end.

He had insightful things to say about all periods of life including the later years, including, you know, death itself. He was a poet with powerful ideas and a lot of experience with that subject.

And I think that he has always entertained me as well. You know, his sense of humor in his best work, it’s very hard to translate.MS. TIPPETT: There’s this story that, when Gandhi wished him another happy decade on his 80th birthday and he wrote back, “Four score is impertinence, five score intolerable.”

MR. ROBINSON: Exactly [laughs].

MS. TIPPETT: But he also wrote very gripping, anguished poetry about aging.

MR. ROBINSON: Yes. The last poems which couldn’t be — they were dictated actually. He couldn’t write them anymore in the middle of 1941. Yes, those are profound, aren’t they? They’re short, but they do deal with the things that concern us all, you know, the meaning of our existence. And the very last poem you’ve also got probably, that’s about the, so to speak, the afterlife, although it doesn’t quite use that word. That, I think, is…

MS. TIPPETT: I don’t think I have that one. Do you have that one?

MR. ROBINSON: Yes, I do. I’m not sure I read it very well, but let me just see.

MS. TIPPETT: Okay.

MR. ROBINSON: Uh, I do have it here in the poetry section of this anthology. Yes, this is the very last poem he wrote in English, of course, originally in Bengali. “The sun of the first day put the question to the new manifestation of life. Who are you? There was no answer. Years passed by, the last sun of the last day uttered the question on the shore of the western sea in the hush of evening. Who are you? No answer came.”

[Music: “Amaar Shakol Niye Boshay Aachhi” by Rabindranath Tagore and Smita Mahalonobis]

MS. TIPPETT: Biographer Andrew Robinson. You can listen again and share this exploration of Rabindranath Tagore at onbeing.org. There you can see some of Tagore’s paintings and listen to music he composed, which we’ve woven throughout this show. Again, that’s onbeing.org.

Coming up…novelist Anita Desai on Tagore’s resonance in her life and art. I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Amaar Shakol Niye Boshay Aachhi” by Rabindranath Tagore and Smita Mahalonobis]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today we’re exploring the modern resonance of Rabindranath Tagore, who lived from 1861 to 1941. He was a polymath — philosopher, writer, painter, musician, social innovator. He was also a friend and occasional critic of his contemporary Gandhi, who called Tagore Gurdev or “revered teacher.”

Tagore won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, the first non-European to receive this honor. A century later, Tagore’s legacy of reverence for the natural world has seen a revival in ecological circles. But much of his vast body of written work is untranslatable, or inaccessibly translated for modern minds. Anita Desai, the celebrated Indian novelist of Bengali descent, would like to change this.

MS. TIPPETT: I wanted to just start by asking a question about you, and Tagore may or may not be implicated in your answer. And then we’ll just really focus in on him. I wonder if you’d just say a little bit about the spiritual and literary background of your childhood and also whether those two things were connected in your imagination growing up.

Anita Desai: Well, I should tell you that everyone assumes that Tagore was part of my heritage. My father was from Bengal. And it should have been, but strangely enough, he was not. Because my father had left Bengal and settled in the north of India in Old Delhi, which is where I grew up. But when I started reading Tagore, I thought, well, he was describing my father’s background. My father himself was a man of very few words, a very silent, withdrawn person, very reserved.

MS. TIPPETT: Say some more about that, about how reading Tagore — you’ve also written this, having recreated your father’s world in a way that he didn’t or couldn’t describe for you.

MS. DESAI: My father had always given us just a few small hints, little stories, about Bengal which were so evocative. And when you tell them to a child especially, they tend to make a great impression. Certainly they did on me.

For instance, he remembered a time living in, you know, small towns, small villages in Bengal, then East Bengal, how the postman used to walk through the forest ringing a bell to scare off tigers and he would chant, “Make way for the mail!” And I thought that was so strange living in Old Delhi where the post was delivered in a much more prosaic way. Chiefly, what I — the picture he created for me with these few things that he told us was of a wonderfully green and riverine landscape which would be so utterly different from arid, dusty Delhi and the north of India. It was a land crisscrossed by rivers and they used to get about by boats especially in the monsoon and the rainy season. It was the only way to get about was in a boat. Even if you were children, you could paddle the boats to school and back.

And Tagore as a young man lived on a houseboat with his family and traveled up and down these rivers. And that is where he collected all the material for his short stories in particularly, because all the tenant farmers, they would come to the boat and tell him about their lives, make their requests and their complaints to him. So he had a great insight into their lives and then they were the material of so much of his fiction.

MS. TIPPETT: I was reading in one of his biographies, you know, his family manor was in an area that was surrounded by poverty and that he was forbidden to leave it, but then, you know, as a result, he became completely fascinated with that world outside and, as you say, with the natural world.

MS. DESAI: I think that two aspects of Tagore’s writing that strike me very much, one is his ability to look into peoples’ lives, to understand their lives with a great intensity, with great perceptiveness. And these were people who were poor, had totally different backgrounds from his own. But he had insights into them, which were so marvelous. I don’t know if this is the moment where I could refer to one or two stories in particular?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, yes. Sure.

MS. DESAI: Well, there’s one little short story of his which was later filmed by Satyajit Ray and became a great classic of Bengali cinema, actually one of the loveliest films you could see. It’s called The Postmaster, and it was inspired by a real postmaster who used to come and visit Tagore and bore him with very long stories.

MS. TIPPETT: Before you go on, you did a reading of The Postmaster, didn’t you for, um — I think I listened to that online.

MS. DESAI: Yes, I did. I recorded it in London.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. And, you know, I was also struck with in that story about how there was great introspection, right? It was kind of the inner life of this postmaster, this person who had an outer life that would not be impressive and it seemed like Tagore was also really working with that reality of the depths that were hidden behind what looked insignificant from the outside in human society.

MS. DESAI: Oh, yes. It think it’s full of a kind of aspiration for another life, which is so prevalent in all his stories. And the other aspect which is so striking is his feeling for the unhappy situation of women in India. But then there was this other side of Tagore’s writing and of his thinking which was really idealistic and spiritual and he could never block that out either. And I think there’s a little — it’s a tiny book, a small play, called, The Post Office, in which this is best represented.

MS. TIPPETT: I believe I read in one of your essays that The Post Office was produced in an orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto a month before the producer and the students of the orphanage were sent to Treblinka. To a concentration camp. Is that right?

MS. DESAI: It’s a curious little play.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MS. DESAI: It’s had a great effect upon people in different parts of the world. And where does it come from? It’s almost like a little breath of air, a little breeze. It’s so little, and yet it’s deeply affected people. Where did it come from? How did it come about?

It’s about this child, Amal, who is very ill and his doctor has refused to allow him out of his room. He’s confined to his bed in his room. And Tagore wrote about this with such understanding because he’d known imprisonment as a child, the imprisonment of the spirit, not the body. And I think it’s in this book and in this child, Amal…

MS. TIPPETT: In The Post Office?

Ms Desai: In The Post Office, that he best creates this feeling of this longing in this child who’s confined to his bed, to his room, who sits at the window watching others who are free to go about. There’s a watchman, Fakir, some boys, a flower girl, Sudha, and they tell him about the hills and woods and rivers where he’s never been. He’s never allowed to go there.

And then one day he sees the Rajah’s post office coming up overnight outside his window flying a golden flag and the watchman assures him that the Rajah himself would soon be sending him a letter, and Amal’s longing for that vast and beautiful earth becomes intensified into his longing for that letter. It arrives and he’s freed.

It is a very strange book and it’s had a strange effect on people, as you just said. It was produced in the Warsaw ghetto by a great child psychologist, Janusz Korczak, who knew what was happening in Warsaw and chose this play to be dramatized, acted, over there. And he accompanied the children of Warsaw when they were led to their extinction. And the other time, the play was produced, Andre Gide, read his translation of it into French over the radio in Paris the night before Paris fell to the Nazis.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s remarkable.

MS. DESAI: It is remarkable because the play itself is so light. It’s almost magical in its manner and yet people have seen these dark undertones to it.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s something that strikes me, that’s curious about when you were talking about one of those stories that your father told you about Bengal, which were so magical kind of once upon a time place. You mentioned the postman and then these two — we talked about “The Postmaster,” Tagore’s short story, and then The Post Office, a little play. What is that? What did the postman and the postmaster and the post office represent? Or what do they represent?

MS. DESAI: It’s a very curious image for Tagore to have pursued in this way.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MS. DESAI: I think it’s always a message from elsewhere, from beyond, from outside that enters into your remote world, but so little ever trickles in. And every time he uses the post office, the postmaster, it’s as if he has had a vision of the outside world.

Tagore suffered terribly from the sense of confinement. He was always longing for freedom of light and freedom of space and he said, “I cherish light and space.” On his deathbed, Tagore had wanted more light. And Tagore said, “If I am capable of expressing my desire, then it will be for

more light and more space.”

[Music: “Danrao Mon Ananta Brahmanda Majhe” by Rabindranath Tagore & Sumitra Roy]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today exploring the legacy of the 20th Century Bengali musician, painter and writer, Rabindranath Tagore. I’m with the novelist Anita Desai.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s something — and you’ve written about this too, how he won his Nobel Prize for literature in 1913 and he was just celebrated by people like Yeats and Ezra Pound. And you wrote that the West’s fascination with him kind of coincided with, as you said, the spirit summed up in Spengler’s “The Decline of the West”, that notion. There was something magical about Tagore. But it also seems like there was a way in which the way people were enamored with him as a kind of mystical, spiritual writer became a way to dismiss him or reduce him.

But his spirituality even in the poetry, you know, even in its purest forms, seems to me always to be connected with reality both in the form of the natural world in very concrete ways and also the human reality including these — the sorrow that is there and the injustice that is there.

MS. DESAI: I think you’re right and it’s most obvious in his poetry. So much of it is lyrical. So much of it is in praise of the natural world and he always wanted to be surrounded by the natural world. He had a hatred of the city. He was happiest when he was out in the countryside and most of his poetry grows out of that. But he was, as you know, as anyone who knows Tagore, he was politically so aware and politically so involved.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, so involved, so engaged.

MS. DESAI: So the real world was always pressing upon him. He wanted to be free of it, but it always was a pressure upon him and he had too much of a conscience and too much of an involvement with this country to turn his back on it. But when he was alone, when he was by himself, he always had this dream of escape.

I’m also very struck by how much a poet who so loved the natural world to whom a leaf, a tree, an insect meant so much was also preoccupied so much of the time with death and how often death seems to have visited him, beckoned to him, wanted to take him away.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, he had a lot of death. I mean, he knew a lot of death in people he loved as well, it seems, all the way through his life.

MS. DESAI: Yes. He knew a great deal of tragedy in his life from the time that he was a very young boy and tragically in love with an older sister-in-law. She was only 18 and she committed suicide and I don’t think he ever got over that because, as an old man in his 70s, when he picked up the paint brush and started to paint, it was her face that he would paint over and over and over again. And then in his lifetime, he lost his wife, he lost several of his children and he knew death.

And yet his belief that death in some way completed life, brought meaning to it, and that is a pain that he wrote about and used a lot of the time.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, there’s, um, some of the things that really struck me, that he wrote these amazing lines about really about age. I mean, I guess it was a period when he was close to when he died. Just this way he was so engaged with that experience, I guess, and articulate, you know, and poetic about it. I don’t know if you — there’s this poem. It’s called “Recovery.”

“Brutal night comes silently,

Breaks down the loosened bolts of my spent body,

Enters my insides, starts stealing images of life’s dignity,

My heart succumbs to the assault of darkness.

The shame of defeat, the insult of this fatigue grow intense.”That is such an incredible way to write about, you know, just this bodily experience of illness and aging.

MS. DESAI: Yes. I think he did write it when he was dying, and yet he was still in complete control. He was able to articulate everything about that experience that few of us are able to imagine or write about.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, and so even in describing, you know, as he says, the indignity, the insult, he makes something beautiful of that, you know, of that description.

MS. DESAI: Yes. And another thing that strikes me so much about his old age and his decline — physical decline was that his spirit remained almost childlike in its vitality. One of the very last poems he wrote, one of the very strangest poems he wrote, he said:

“Today I imagined the words of countless languages

To be suddenly fetterless,

After long incarceration in the fortress of grammar.

Suddenly up in rebellion, maddened by the stamp, stamping of unmitigated regimented drilling.

They have jumped the constraints of sentence,

To seek free expression in a world rid of intelligence,And he goes on about the way these words have broken free and are galloping all around him and dancing…

MS. TIPPETT: Free from the bonds of grammar. [laugh]

MS. DESAI: Yes, even the bonds of grammar. And he ends it:

“In my mind I imagine words thus shod of their meaning,

Hordes of them running amok all day,

As if in the sky there were nonsense nursery syllables booming —

Horselum, bridelum, ridelum, into the fray…”Imagine a dying man, one of the last things he wrote, was of this amazing fantasy of freedom.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. You know, it’s interesting, isn’t it? I mean, one of his biographers, um, in this biography that you actually wrote the foreword to, said, you know, “Tagore’s found everywhere in Bengali life and yet he is lost.” And, you know, I learned in particular from your writing that, I mean, is the Indian national anthem a song that he wrote? Is that true?

MS. DESAI: Yes. The Indian national anthem and the Bangladeshi national anthem too. Yes. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And also that every Indian school child recites this poem of Tagore, “Where the Mind is Without Fear,” which is beautiful. I want to ask you about this. You’ve mentioned this in a few essays, but you always say, “every Indian school child recites, however reluctantly [laugh], ‘Where the Mind is Without Fear.’” Is that reluctance just because this is something memorized?

MS. DESAI: Because it’s compelled. It’s a compassion. Every child must learn this, yes. If a child were to come upon it on his own, of course, it would have a very different effect. But if it’s prescribed, then one doesn’t see it in quite the same way.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you know it? Do you have it in front of you?

MS. DESAI: I don’t have it with me.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ll just read it.

“Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms toward perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by Thee into ever-widening thought and action —

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.”It’s a prayer.

MS. DESAI: It is a prayer and, of course, Tagore was writing that as a patriot and he was also writing it as an educationist. That was the other aspect of his life. He so much wanted to change education the way it was in India. He wanted to set students free. He’d suffered himself at the hands of very unimaginative teachers and a very unimaginative way of teaching.

MS. DESAI: There seems to be practically no aspect of life that he didn’t try to touch, to alter, to somehow bring around to his ideal of how things should be. And, of course, they so often ended in tragedy, that you would think he would have become a very cynical man at the end of his life. But I think he had far too much compassion and far too much imagination to ever allow himself to become truly cynical.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s these words he spoke on his 80th birthday. “As I look around, I see the crumbling ruins of civilization like a vast heap of futility, yet I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in man.”

MS. DESAI: It’s true. He very rarely mentioned God, that’s not a word that he — that figures in his vocabulary. He really believed in the divinity of man, or the divinity that man is capable of, although so rarely achieves.

MS. TIPPETT: Although I was fascinated to read that when Gandhi was fasting, again within his campaign to eradicate untouchability in the 1930s, that Tagore traveled to be with him and that he led the group in prayer when Gandhi broke the fast. I read that he read these lines from his book of poems which won him the Nobel Prize. It’s beautiful again.

“When my heart is dry and parched, come with a merciful shower

When grace has departed from life, come with a burst of song.”MS. DESAI: I think that must be the most wonderful reverence anyone could have shown Gandhi. It would surely have stirred him deeply. It must have meant a great deal to him.

MS. TIPPETT: What does Tagore mean to you? I mean, let me just kind of ask a question. How does his imprint on the world, you know, Tagore’s legacy which continues to roll around in the world in many forms? I mean, how does it nourish you in your 21st century life?

MS. DESAI: I do think that he must be the most Indian of all Indian writers. As I say, I was never made to read Tagore as a child. Yet, when I started writing, and this was before I had read Tagore, I was writing on many of the same themes, the confinement of women, the denial of freedom, of free thinking to women especially.

And also the fact that, if you do pick up Tagore, if you can bring yourself to overcome a resistance to that definitely Victorian, old-fashioned, out of fashion, manner of writing now, you do break through to a mind that is so vast and so complex that it really does ask of one a new way of study, a new way of finding how to relate to his work. Perhaps it’s also a particularly Indian way of thinking and being and writing and speaking that we all do share.

[Music: “Gahana Ghana Chailo” by Srikanto Acharya]

MS. TIPPETT: Anita Desai’s novels include include Clear Light of Day, The Village by the Sea, and Fasting, Feasting.

You can listen again or share this show with Andrew Robinson and Anita Desai, on our website onbeing.org. There you’ll also find examples of Tagore’s paintings as well as our interview with Bengali novelist and Tagore translator, Amitav Ghosh.

[Music: “Ami Kaan Pete Roi” by Bonnie Chakraborty]

And, don’t forget that we now have a free On Being app. iPhone and iPad users, go to the iTunes store; Android users, download the mobile app in the Google Play store.

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Chris Jones, and Julie Rawe.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.