Mark Kermode

The Exorcist

The Exorcist is known for being absolutely terrifying, but film critic Mark Kermode argues that it’s also a masterpiece. He was too young to see the movie when it was released and had to wait six years before he could watch it in a theater. Decades later, he has made documentaries about The Exorcist, written long essays and a book about it, and even became friends with the movie’s director and screenwriter. But he says every time he watches the movie, he’s still taken back to the experience of transcendence and magic he experienced when he watched the movie for the first time.

Image by Julia Kuo, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Mark Kermode is the chief film critic for The Observer, host of the podcast Kermode On Film, and co-host of Kermode & Mayo's Film Review on BBC Radio 5 Live. His books on film include Hatchet Job, It’s Only A Movie, and How Does It Feel? A Life of Musical Misadventures.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, fellow movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with Mark Kermode about the movie that changed his life, The Exorcist. Don’t worry if you haven’t seen it because we’ll give you all the details you need to follow along. And hopefully — if you’ve been too scared to see it — we’ll have changed your mind by the end of this conversation.

[music: “Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 10 (Sehr Langsam Und äusserst Ruhig)” by Anton Webern]

Everything that I read about The Exorcist over the years, just as a movie fan and that I heard about from people who watched the movie, everything about it was about how shocking it was, how scary it was. But no one ever told me how good it was. This is a movie that, quite frankly, is a masterpiece in movie making. And that’s something that I wasn’t prepared for when I watched it for the first time.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

[music: “String Quartet” by Krzysztof Penderecki]

The Exorcist takes place in Georgetown in Washington, D.C., and it revolves around a twelve-year-old girl and her demonic possession. It’s terrifying because it’s a child that you’re watching — and Satan speaking through a child — but it’s also terrifying because there seems to be no way to help her. Her mother tries her best, goes to doctors, psychiatrists, and then finally turns to the Catholic Church as a last resort, to a priest named Father Karras, trying to figure out what exactly is living within her own daughter.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

My brother, who’s a big movie fan as well, has been trying to get me to watch The Exorcist since I was a teenager. And the only person who could really do this for me, who could get me to sit down and watch this movie from beginning to end, is my living movie prophet, Mark Kermode. He hosts the podcast Kermode on Film, and is the co-host of my favorite podcast, Kermode and Mayo’s Film Review from the BBC. He’s also kind of been the foremost expert on The Exorcist. He’s made documentaries about The Exorcist; he’s written about it, long essays and books; and he also even became friends with the director, William Friedkin, and the screenwriter, William Peter Blatty. This is a movie that Mark lives with, and for him it’s a movie that has not only changed him as a person but has also changed the way he views movies.

Ms. Percy: I’d like you to just go back in time for a couple of seconds — ten seconds, and I’ll watch the clock— and I’d like you to go back in time. I’d like you to close your eyes and think about that first time that you saw The Exorcist. Think about how old you were, where you were, and how it made you feel. And I’ll chime in when those ten seconds are up.

So tell me what memories came up for you.

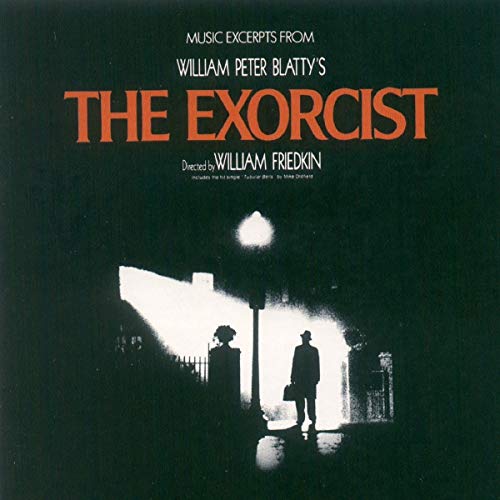

Mark Kermode: Well, I mean, the weird thing is, this is something that I think about pretty much every day. [laughs] When The Exorcist first came out, I was 10 years old. And I remember really clearly going to school on the tube train, and there were posters for the film everywhere. And the poster was that iconic image of Max von Sydow standing outside the house on Prospect Street, just in a black silhouette with — in England, the light behind the poster was yellow; in America, you had these posters with the purple tops. So I knew the image, and it struck me to the core.

And our news programs were full of stories that had basically come over from America, about this film that had had this extraordinary effect on audiences: that people were being carried out of screenings; that people were having hysteria and fainting, and the whole country had gone on a possession jag. And the novel was everywhere — I mean, absolutely everywhere. It was paperback novel, which had a white banner across it which said, “See the movie. It’ll be the most electrifying thing that ever happened to you.” So I was seven or eight years away from being able to see the film, because they were quite strict about it. There were some movies, some X-rated movies that nobody really cared whether you went to see them. But movies like Clockwork Orange or The Exorcist, they were very strict about.

So I then had the best part of six years obsessing about a film I had never seen. The idea of it terrified me — absolutely terrified me, put the fear of God into me. I remember so clearly how scared I was by the idea of it. But I was also completely fascinated by it. And so, I read the book. I read the screenplay that William Peter Blatty had published in his book — William Peter Blatty on The Exorcist — which had his original screenplay and then a transcript of the finished film. I obsessed about The Exorcist, and I basically —

Ms. Percy: [laughs] This is what you were doing instead of chasing girls.

Mr. Kermode: Pretty much, because what I did when I was kid was I went the movie. That’s what I did the whole time. So I basically had seen the film before I ever saw the film. And then, what finally happened was, I must’ve been 16, maybe 17, and I went to a late night double bill to see The Exorcist. So by the time The Exorcist is about to come on, it’s about midnight.

Ms. Percy: Oh, wow.

Mr. Kermode: And the film starts, and it starts with the Warner Bros. logo, which comes up, and there’s this sound, which is actually the sound of Friedkin and Jack Nitzsche, I think, rubbing their fingers over a glass of wine. You know, that kind of wooo — that sort of thing, the glass theremin sound.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

[music: “Iraq” by Krzysztof Penderecki & Jack Nitzsche]

And then we begin with this sequence in Iraq, and I am in palpitations, because the Iraq sequence is a brilliant scene setter, but it goes on for a while. But I remember so clearly, sitting in the cinema and looking around at other people, thinking, “Look — over there, there’s a middle-aged lady. She’s gonna be OK, so you’ll be all right. And look over there — they don’t look particularly hard. If they —” I was in fear of my life. And I remember, years later, when I became friends with Friedkin when I was making documentaries and things, and he said, “The thing you have to understand is that after the first reaction to The Exorcist, people were scared before they got into the cinema.” He said it was like walking down a street that you’d read in the paper, there was a murder there the night before. He said, “They were scared before they got into the theater.” Well, I’d been scared for six years before I got into the theater.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

Ms. Percy: So I have to ask, what toll does that take on you as a kid, and also, how do your parents react to watching you obsess in this way? Did they say, “You can’t see this”? I believe you grew up Anglican, if I’m not mistaken.

Mr. Kermode: Yeah — I was brought up as a Methodist, and then I’m Anglican now because — well, I’m C of E now, which is Anglican. There’s a joke about the Church of England, which is, “You don’t lose your faith. You just can’t remember where you left it.” So my parents knew that cinema was the thing that I was interested in, but they also knew that I was really, really interested in horror. And when the horror thing began, I’d come downstairs at night and watch old Hammer reruns on our black-and-white television, with the volume turned down so that my mum and dad couldn’t hear. And they weren’t down on it in any way. So I think what they thought was, if you’re interested in anything, that’s a good thing.

And I’ve always said this — there’s a great vilification of horror movies. People always “Oh, they’re bad for kids,” or “They do terrible things.” If you are a slightly lonely child — and I wasn’t unhappy-lonely; I was very happy in my own company, and my ideal thing would be to go, on my own, to the cinema to watch a movie — horror movies, they do speak to you.

And I’ve met so many people over the years, because I’ve spent a lot of time working in the field of horror films, who have that same thing. They either work for you, or they don’t. And if they don’t, you can’t explain it. It’s like if somebody says, “What do you think of opera?” I go, well, to me, opera is — I can appreciate it, but I don’t “get” the thing.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, it doesn’t speak to you.

Mr. Kermode: And it’s the same with horror movies. The difference is, no one tells you that if you listen to opera, you’re gonna turn into a serial killer. And then we’d go to these horror late-nighters, where there would be a lot of individuals, who — we’d never really talk to each other, because we were sort of slightly socially awkward people. But you’d kind of see the same faces over and over again, and you sort of felt a kinship. If you were a bit of an outsider, horror movies were like your friends.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

Ms. Percy: I love the way — and I have to say, I’m such a huge fan of your writing…

Mr. Kermode: Thank you.

Ms. Percy: … so I will be quoting you back to yourself a lot. I hope you’re comfortable with it.

Mr. Kermode: As my wife once said, I don’t fish for compliments, I troll for them.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] I love that. Well, I have been, I confess, a person who has never really given horror its due. And reading you write about it, there’s this wonderful way that you say, “People talk endlessly about the damaging effects of horror movies, but too little is heard about the life-affirming power of being scared out of your mind, and in those very rare cases, out of your body. You ask me if I think there is more to this world than the grim realities of aging, disease, and death, of mourning and loss, and I will refer you to that first viewing of The Exorcist, during which my imagination took flight, my soul did somersaults, and the physical world melted away into nothingness around me. I don’t think that there’s a spiritual element to human life. I know it because I have experienced it firsthand, and I have horror movies to thank for that blessing.”

I love that.

Mr. Kermode: Thank you.

Ms. Percy: Tell me a little bit more about that experience, what you’re talking about, that aliveness, that presence that you had, being taken away by The Exorcist.

Mr. Kermode: That experience — years later, I would talk to Bill Blatty, who wrote The Exorcist, and Bill had some sort of conflicts about how the film was received, what the film meant to people. He was very concerned that, because certain key sequences had been taken out of it, that the message of it wasn’t clear. And the message, from his point of view, was very clear. It is, it will all be alright in the end. God is in his heaven; there are angels, because there are demons — you know, if there are demons, then there are angels. And he was very, very clear about it. And Bill was a very religious man, and that was what the story was about for him.

But he said — we were talking quite candidly at one point, and he said, “The thing is, when you watch that film, you are alive; you are having an experience. And whether that experience is good or bad, you are alive, and you are aware of it.” And what it means is that there is a thing that horror movies can do — and to some extent this goes into roller coasters, all that sort of stuff — it makes you alive by confronting you with the spectacle of something else.

But it’s more than just, oh, you’re experiencing something dangerous in a safe environment; it is, in the genuine sense of the word, transcendent. Now, from my point of view, that sort of almost out-of-body experience that I had, watching The Exorcist, was wholly positive, wholly positive, because it was a form of transcendence. And there are moments when cinema does that to you, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s a horror movie or whether it’s a love story or whether it’s a thriller or science fiction — it’s something that makes you think there is more to this world than this chair that I’m sitting in and this auditorium that I’m sitting in.

And the other thing that I think is really important — one of the purposes of this discussion is the movie that changed me, that taught me something — and one of the things that The Exorcist taught me was, people take away from that experience what they bring to it. And Friedkin has always said this. He said, when I saw the film, I saw God. Other people saw it, and they saw the devil. I’ve seen that film a million times, and every time, I take different things away from it. But what I think’s important is that, for me, it was — I brought so much to it. Six years of stuff, I brought to that screening, and the film, literally like a prism, shone it back at me. And it didn’t drop a beat.

And I — that’s why I think it’s such an impressive film, because for somebody to go to a movie with such baggage, and for the film to go, pa-dum — it works like a spell, because there’s something about it, the way — it’s like a piece of music. You can’t really explain why a brilliant piece of music — you can say, “Well, there’s — this contrapuntally does that —”

Ms. Percy: You can analyze and critique.

Mr. Kermode: But it won’t get you to the ultimate answer, which is why does that film work.

Years later, I went to Georgetown, and I walked up those steps. And I walked to the front of where the house should be — obviously, it’s different in real life. And again, it was that incredible feeling of, I’m walking into something that I’ve already been into. And that déja vu — that is an uncanny experience, and uncanny experiences tell you that there’s more to life than just this.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

[music: “Polymorphia” by Krzysztof Penderecki]

Ms. Percy: If you’re enjoying my conversation with Mark Kermode, consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts. It really helps people discover This Movie Changed Me, and we also just love hearing what you think. As always, thank you for helping us build our movie-loving empire.

[music: “Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 10 (Sehr Langsam Und äusserst Ruhig)” by Anton Webern]

Ms. Percy: I love that you brought up that quote from William Friedkin, the director of The Exorcist, that The Exorcist is a film that gives you what you bring to it, because I grew up in an Evangelical household. My parents were Catholic in Colombia, in Latin America, and they converted in their college years to a Protestant denomination. And when this movie was re-released in the theaters when I was in high school — I’m 37, and it was released in 2000 again — I remember they talked about how I could never see this movie, because people had gone mad, and they put so much fear into me about this movie that I just was terrified. I have such pain for you, those six years that you spent, [laughs] thinking about this.

But what I love about what you’re saying is that when I finally saw it — which, by the way, was the first time, this week, because of you —

Mr. Kermode: Oh, wow. I’m so sorry. [laughs]

Ms. Percy: No, I’m so grateful to you, for two reasons: First of all, it’s an amazing movie.

Mr. Kermode: It really is.

Ms. Percy: No one ever told me that. No one told me that in addition to terrifying you, it was also gonna be this work of art. I had no idea. And the second thing is that watching it, I felt like my faith was strong enough to sustain me through the experience. [laughs] It was holding up this mirror to me in that beautiful way, as you said, that I was bringing to it what I wanted to, and it gave me the sense of, “I am gonna be OK, because if there are devils, then there are angels — and human beings are complex, and we get through it.”

Mr. Kermode: And the interesting thing is that from a theological point of view, the story is immensely encouraging. As you know, if you go into it with a Catholic perspective, it’s pretty straight down the line: the forces of good triumph over the forces of evil. Karras commits the ultimate sacrifice, and he is redeemed and saved, as is the young girl. And so that’s the story.

If you don’t believe in the theology of it, the film works on an equal level, just as a film about something that is happening — because the whole point of the film is, it’s not her. There’s so much of that film is looking at other characters. It looks at Ellen Burstyn as she recoils in terror. It looks at the doctors as they are baffled and amazed. It looks at Father Karras as he hears the demon taunting him. There’s almost more concentration on all the characters reacting to what’s happening than what’s happening. And that’s kind of the key to it.

That’s why Exorcist II is the stupidest film ever made, because in Exorcist II, it’s, oh, no, it is all about her.

Ms. Percy: Exactly.

Mr. Kermode: That’s what it’s about.

Ms. Percy: So let’s just forget everything we’ve established. [laughs]

Mr. Kermode: Just throw all that out the window. That’s all nonsense. Ms. Percy: I love that you brought up how the characters are portrayed. I was so impressed with how Chris, the mother, played by Ellen Burstyn — you believe how terrified she is about her daughter, because the movie takes all of that time — that slow burn you talked about — in setting up her life, her intimate relationship with her daughter. You just really understand and know this woman. And so, when this happens, when you see her daughter become possessed, you just feel so much for her.

Mr. Kermode: One of the most important sequences in the film is a very, very incidental sequence when Chris is putting Regan to bed, and Regan’s got a cover of the magazine. It’s a magazine image of her and her daughter on the front of it.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

And they have a little, incidental conversation. She says, “Oh, I don’t like that cover. You look so mature.” And it’s a couple of minutes long. But you absolutely believe that they are mother and daughter and that they have history, that they have a past, that they have shared quips and foibles.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

It also sets up — one of the brilliant things about the film is, everything in it is prefigured by something else. So that moment when she looks at the magazine, she says, “Oh, you look so mature” — there is something in the film about “you’re not my little girl anymore.”

Ms. Percy: And Regan is the little girl played by Linda Blair.

Mr. Kermode: Regan is the little girl played — played brilliantly by Linda Blair, brilliantly played by Linda Blair —

Ms. Percy: Who I had to Google, “is she OK?” after seeing this movie.

Mr. Kermode: Yeah, she’s great. No, and I have met Linda Blair. A sounder, nicer, more down-to-earth, solid person you would —

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Thank God.

Mr. Kermode: Just a top — all-round top person and a really hardworking actress and brilliant in that film.

But it’s those incidental details that mean that when stuff starts kicking off, you feel that horror. When Chris is talking to the doctors, and they’re saying, “Well, maybe it’s…” and she says, “99 doctors, and all you can tell me — did you see what she was doing? She’s acting like she’s a —” And then, when she says, “You show me Regan’s double, same everything now, the way she dots her I’s, and I know, I’d know in an instant that it’s not my own. I’m telling you that that thing is not my daughter.”

And that works, because half an hour, 45 minutes before, you were seeing her and Regan behaving exactly like a mother and daughter. So all the way through the film, it’s — all the scenes that seem incidental are really doing the heavy lifting so that when the other stuff happens, the stuff that everyone talks about, it works because of everything that’s gone before. It’s just genius.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

Ms. Percy: As a person of faith, I really appreciated that they started with doctors, and the medical scenes were included, because it goes to this idea of how you can’t prove faith. You can’t prove any of what’s happening to her, and she has to go to a priest for help. She tried every logical thing she could, and it didn’t work. And that, to me, almost feels like often, when I have conversations with atheists, I’m like, I get it. None of this is logical. [laughs]

Mr. Kermode: And of course, the great irony of the film is that Chris, who is nominally an atheist, goes to the priest, and she is trying to convince the priest that her daughter is possessed, and the priest doesn’t believe her. So it’s like — the role reversal is brilliant. The Catholic priest doesn’t believe that the kid is possessed, and the atheist mother does. And it’s one of the great ironies at the center of the film, is that it’s — you don’t even notice it’s happened, that she, who doesn’t believe in any of this stuff, is saying, “I think my daughter’s possessed,” and he, who does believe in all this stuff, is saying, “Come on, we’re gonna have to get into a time machine and take you back to the Dark Ages, because we don’t do this anymore.”

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Yes. And this is why, from what I’ve read, when that film came out, the Catholic Church actually thought it was a great ad for them. [laughs]

Mr. Kermode: Well, I know for a fact that there was a huge number of people who came straight out of the cinemas from seeing it and went straight into a church.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] The reasons probably varied. [laughs]

Mr. Kermode: Yeah, but again, I would talk to Bill Blatty about this — I miss Bill terribly. He was a brilliant — such a funny man; he was a comedy screenwriter, and he had happened to write The Exorcist. But he was the kind of person, if you wanted to engage him in a theological discussion, it was great, because he enjoyed nothing more than that.

And his feeling about it was that what the film did was, it at least got people thinking about theology in a secular age. And it’s true. Find me another film, outside of a Hammer or a Dracula or something like that, in which the hero — well, the two heroes — are priests.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

Ms. Percy: I’m so curious — there are so many layers to this movie, clearly. There’s the layers that you find in the sense of how it was made and the true masterpiece element of the filmmaking, which you, as a film critic, can find; and a film scholar. But I’m so curious as to what it continues to give you and what you continue to bring to it. You say, yourself, you’ve seen it hundreds of times, and you keep going back to it. Does it give you a new perspective on your faith? Does it give you perspective on being a parent? What things do you bring to it now that you didn’t when you first saw it as a kid?

Mr. Kermode: It’s so hard to say. I think that every time I see it, I’m reminded of the first time I saw it. It is, for me, a kind of primal experience. I think it’s interesting that — I write about horror movies quite a lot. And I used to get this thing — people used to go, you go to church? And I go, yeah, yeah. And they went, well, how can you be into horror movies and go to church? And I was like, how long have you got? It’s like, seriously? The most violent film I’ve ever seen in my life is The Passion of the Christ.

Ms. Percy: Oh, my God, yeah. [laughs]

Mr. Kermode: I have literally never seen a more violent film than that.

Ms. Percy: Agreed.

Mr. Kermode: Here’s the thing. You don’t obsess about The Exorcist as long as I have without being fundamentally interested in questions of faith, OK? And when I was younger, I used to do a lot of angsting about trying to figure everything out and — but — how and why and blah blah blah blah blah. And as you get older — well, as I get older — what I think is this: Most of my life — I’ve gone to church, and it’s always worked for me. I don’t presume for one minute to understand the mysteries of the cosmos, and I’m no longer wrestling with any of that stuff, because I think that there is more to the world than this, and beyond that, I think that you should try and be decent and honest and fundamentally not spend your life screwing people over. Whatever anybody else believes is absolutely up to them. I don’t think it’s important to know or not to know. I don’t need or want proof of things. But a film like that, that has that kind of effect, just reminds me that there’s magic in the world; I mean, magic — proper magic.

Ms. Percy: It’s what makes going to the movies a church in itself, right? I agree with you; I know you’ve written about that, as well. And for me, I didn’t grow up going to a church building, ever; we met in the house that my parents lived in. But going to the movie theaters, for me, is a church. That’s the church experience for me. And it is because you’re amongst other people; you’re alone together, and when you can experience the transcendence that something like The Exorcist gave you and that I experienced this week when I watched it …

Mr. Kermode: Oh, I’m so glad. [laughs] That’s great.

Ms. Percy: It is magic.

Mr. Kermode: It is. It is. It’s never let me down. It’s never let me down after all these years.

[excerpt: The Exorcist]

[music: “Tubular Bells” by Mike Oldfield]

[music: “Fantasia for Strings” by Hans Werner Henze]

Ms. Percy: Mark Kermode is a presenter, writer, musician, and my favorite living movie prophet. I can’t recommend Mark’s work enough — I first discovered him through the wonderful BBC radio show and podcast Kermode and Mayo’s Film Review, and he now also hosts his very own podcast — Kermode on Film. Mark’s work and the church of Wittertainment sustains me, so I say a very Minnesotan hello to Jason Isaacs.

[music: “Are You Scared” by Oiki]

The Exorcist was produced by Hoya Productions and distributed by Warner Brothers. The clips you heard in this episode are credited entirely to them. The soundtrack was released by Warner Brothers Records and should be classified as a music genre we’re calling “hella creepy.”

Next time on This Movie Changed Me, we’ll be talking about the beautiful Pixar movie, Coco. You can find it streaming in all the usual places, including Netflix. Prepare to have the soundtrack stuck in your head for weeks.

The team behind This Movie Changed Me is: Maia Tarrell, Chris Heagle, Tony Liu, Kristin Lin, and Lilian Vo. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota Land. And we also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett and Becoming Wise. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

I’m Lily Percy — and I promise you, if you watch The Exorcist, you will be ok.

Reflections