Matthew Olzmann

Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem

In this love poem, Matthew Olzmann writes about his wife — the poet Vievee Francis, whose poem for Matthew was featured in the previous episode — and the reasons why their marriage might work: her courage, her tenacity, her quirks, her multiplicities. He recounts instances of her generosity and lands on a story of how, when she was down to her “last damn dime,” she still bought a bottle of Mountain Dew for him, because she knew he loved it. This is a cinematic and musical poem, making exquisite use of a particular object: a bottle of soda, holding fizz in it, and symbolizing more love than it could contain.

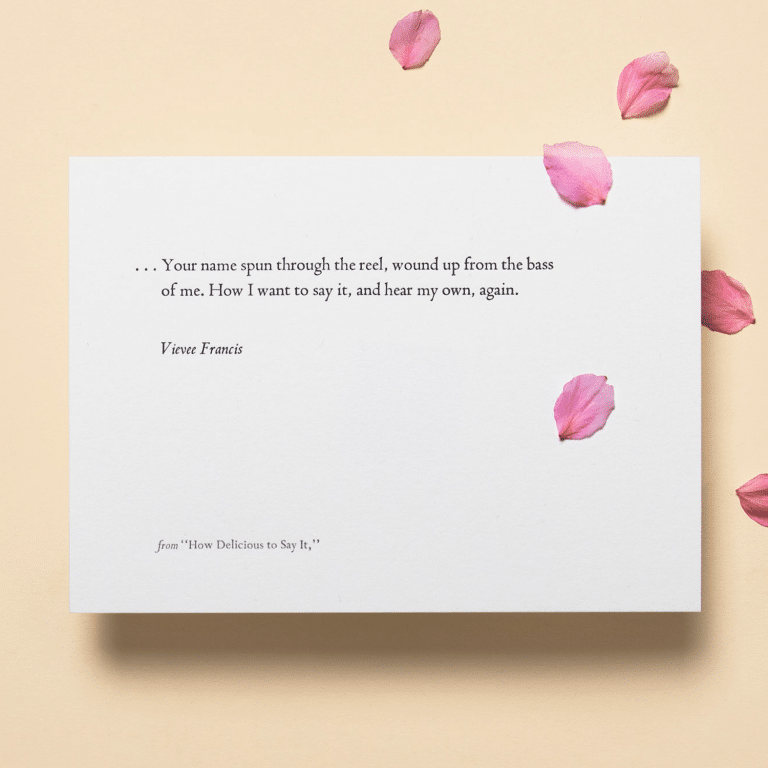

Letterpress art by Myrna Keliher.

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Matthew Olzmann was born in Detroit, Michigan. He received a BA from the University of Michigan–Dearborn and an MFA from Warren Wilson College. He is the author of Contradictions in the Design and Mezzanines, winner of the 2011 Kundiman Poetry Prize. Olzmann has received fellowships from the Kresge Arts Foundation and Kundiman, among others. He teaches at Warren Wilson College and lives in North Carolina with his wife, the poet Vievee Francis.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama. And when I was a teenager, late one evening I saw my father come into the kitchen, grab a slice of bread, and eat it. I think his blood sugar had dropped. And there was so much about that moment that struck me. I was a teenager with angst about myself and everybody around me, and noticing a moment of vulnerability in somebody else struck me. And I think that was telling me I needed to be a poet, because I had to do something with what I’d seen. And over and over again, the more I’ve written poetry and read poetry, the more I realize that moments, simple, observed moments, are calling out to be written about.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem” by Matthew Olzmann:

“So here’s what I’ve got, the reasons why our marriage

might work: Because you wear pink but write poems

about bullets and gravestones. Because you yell

at your keys when you lose them, and laugh,

loudly, at your own jokes. Because you can hold a pistol,

gut a pig. Because you memorize songs, even commercials

from thirty years back and sing them when vacuuming.

You have soft hands. Because when we moved, the contents

of what you packed were written inside the boxes.

Because you think swans are overrated and kind of stupid.

Because you drove me to the train station. You drove me

to Minneapolis. You drove me to Providence.

Because you underline everything you read, and circle

the things you think are important, and put stars next

to the things you think I should think are important,

and write notes in the margins about all the people

you’re mad at and my name almost never appears there.

Because you make that pork recipe you found

in the Frida Kahlo Cookbook. Because when you read

that essay about Rilke, you underlined the whole thing

except the part where Rilke says love means to deny the self

and to be consumed in flames. Because when the lights

are off, the curtains drawn, and an additional sheet is nailed

over the windows, you still believe someone outside

can see you. And one day five summers ago,

when you couldn’t put gas in your car, when your fridge

was so empty—not even leftovers or condiments—

there was a single twenty-ounce bottle of Mountain Dew,

which you paid for with your last damn dime

because you once overheard me say that I liked it.”

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

I chose this poem because of its humor and because of its clever use of deflection and privacy, of its attention to love in all the small idiosyncrasies and privacies of the person, and also because I love list poems, and this is a very definite kind of list poem. The word “because” occurs 12 times in it. And so in a certain sense, this is a list of “becauses,” and I think it’s a lovely gathering of all these reasons why this poet, Matthew Olzmann, is in love with his wife, Vievee Francis, the woman he’s married to.

He’s paying attention to so many interesting things. He notices that she wears pink. And we hear that she writes and reads, and reads critically. He’s looking at what skills she has, what she can do with her hands. We’re hearing about her humor and memory and habits, and then silly stories about writing the contents of a moving box inside it. But that time they moved, where were they moving from and where to? There’s a sense of history happening here. And there’s opinions that she has, and her generosity, her attention to sharing what she reads with him, and her way of coping with being angry or frustrated. And then there’s ways of even acting on what she’s reading, like seeing a recipe in a book about Frida Kahlo and thinking, “I’m gonna cook that recipe”; and then her critical attention to books; and then that really interesting part about privacy — having the curtains closed and a sheet nailed over the top of it. He’s noticing what it is that she’s uncomfortable with.

And what we see over and over again is how his attention is turned toward somebody in a way where that attention is received with love. I think in many ways this poem has a tension held between it between noticing and courtesy, between observing somebody but also knowing that, even when they’re observed, they are still a private person; and within that kind of understanding of two individual people who continue to be two individual people, even when they’re married, that that dignity and respect for their individuality is the very thing that means their observation of each other is an observation of love.

[music: “Simple Vale” by Blue Dot Sessions]

In this poem, the woman being described, Vievee Francis — and we’ve already heard the poem from Vievee Francis which she has written and dedicated to Matthew — is extraordinarily observant but, nonetheless, doesn’t necessarily want to be seen from the outside unless she’s choosing it. And the poet, too, is observant. The poet is writing in a certain way where he’s kind of deflecting the fact that it’s a love poem by saying it’s a Mountain Dew commercial, which of course it’s not, it’s a love poem. And the “you” in the poem, even when she’s writing, she’s writing on the inside of boxes. And so there’s a certain recognition of what your own private conversation with yourself is, the things you keep quiet in yourself.

And I think that can sometimes be the kind of love that can take a long time to get to. In the first flushes of love, you can sometimes want to change somebody to be somehow doing the things that you understand and definitely don’t annoy you. And this kind of love seems to have matured into the sense of where people are just observing each other in the idiosyncrasies of their life and in the way that things like that are funny; but also, they’re not trying to change each other.

[music: “Tiny Water Glass” by Blue Dot Sessions]

One of the things about this poem is, on a formal level it uses this thing called objectification. And that, when you’re writing poetry, isn’t the way that we use it to describe derogatory behavior. This poem objectifies — as in it makes an object of — it objectifies love in the form of a bottle of Mountain Dew. And I suppose one of the invitations of this poem is to think, what object would you use to tell the story of your relationship with somebody you love? It might be a train ticket or a cinema ticket, or it might be a tattoo. It might be all kinds of things where you’d go, “This object, this thing sums up a story of love between me and another person” — a friend, a sibling, a partner.

And I think one of the brilliant pieces of technicality in this poem is that this poem is focusing our attention on the bottle of Mountain Dew, and it’s even calling the poem a commercial for Mountain Dew, but yet we know absolutely, throughout it, that this isn’t about a bottle of Mountain Dew, that this is all about what that means and what’s behind it. It’s all about the fact that the fridge was empty. There could’ve been so many things to spend the “last damn dime” on except that one thing, which was based on listening and the one time that he said he liked this drink, and she purchasing it for him.

[music: “Careless Morning” by Blue Dot Sessions]

This poem makes brilliant use of alternative lengths of line. Listen to this: “Because you memorize songs, even commercials / from thirty years back and sing them when vacuuming. / You have soft hands.” Boom. I think the alternated way within which there’s elongated lines that stretch out over line breaks, and then a four-word line, “You have soft hands” — it means that this poem is constantly shifting. You can’t read this as a da-dum, da-dum, da-dum, da-dum, / da-dum, da-dum, da-dum poem. It doesn’t have a metric beat. And I think within the context of that, what this shows us is that the person who’s being observed in this poem is many things.

And that’s one of the ways that a form of a poem has to have a much bigger purpose. And the much bigger purpose of using long lines and short lines, and ways that the lines even repeat — “you drove me to the train station. You drove me / to Minneapolis. You drove me to Providence” — these repeated lines, other short lines, and then these really long lines, they’re all showing us that the object of the poem, the person who’s really being described, is many things at once; that she can’t be narrowed down to just one thing. She’s not just a poet. She’s not just a partner. She’s not just a reader. She’s not just a critic. She’s many things, all at once.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

Years ago, I remember reading E. M. Forster’s book Where Angels Fear to Tread, and there’s this throwaway line in the middle of it, a beautiful throwaway line, and it’s pretty much the only thing I can remember from the book. And the line is: “For it is a serious thing to have been watched. We all radiate something curiously intimate when we believe ourselves to be alone.”

And I remember reading that book years and years ago and being so struck by the quality of looking at somebody who you love, and what it’s like to see somebody who you love, in a moment where they might not know that you’re looking at them, and that even if they do notice you noticing them, that they know that you’re looking at them with love. So there’s no sense of being cornered or being observed in something that you don’t want to be observed in, but something really beautiful in watching somebody who you love.

So I think this poem has a certain calling-out to people who are engaging with it. It is a poem that is entirely engaged with the small universe between two people who love each other. And as a result, I think the invitation of this poem is for the readers or the listeners to the poem to do something similar — to notice those we love, and to notice being noticed, as well, and to share love in that noticing. And this poem knows that love is shown in this kind of attention to each other — not to pigeonhole them or their contradictions or to judge them, but simply to notice what’s important to them. And in honoring what’s important to them, we might honor that part of them that we might never know fully, but that nonetheless will always be present to us, right in front of us.

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem”:

“So here’s what I’ve got, the reasons why our marriage

might work: Because you wear pink but write poems

about bullets and gravestones. Because you yell

at your keys when you lose them, and laugh,

loudly, at your own jokes. Because you can hold a pistol,

gut a pig. Because you memorize songs, even commercials

from thirty years back and sing them when vacuuming.

You have soft hands. Because when we moved, the contents

of what you packed were written inside the boxes.

Because you think swans are overrated and kind of stupid.

Because you drove me to the train station. You drove me

to Minneapolis. You drove me to Providence.

Because you underline everything you read, and circle

the things you think are important, and put stars next

to the things you think I should think are important,

and write notes in the margins about all the people

you’re mad at and my name almost never appears there.

Because you make that pork recipe you found

in the Frida Kahlo Cookbook. Because when you read

that essay about Rilke, you underlined the whole thing

except the part where Rilke says love means to deny the self

and to be consumed in flames. Because when the lights

are off, the curtains drawn, and an additional sheet is nailed

over the windows, you still believe someone outside

can see you. And one day five summers ago,

when you couldn’t put gas in your car, when your fridge

was so empty—not even leftovers or condiments—

there was a single twenty-ounce bottle of Mountain Dew,

which you paid for with your last damn dime

because you once overheard me say that I liked it.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem” comes from Matthew Olzmann’s book Mezzanines. Thank you to The Permissions Company on behalf of Alice James Books, who gave us permission to use Matthew’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections