Gal Beckerman

How Newness Enters the World

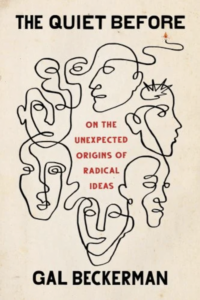

When time becomes history, different dynamics come into focus than the ones that are at any moment screaming for attention. The title of Gal Beckerman’s book intrigues and compels: The Quiet Before. He’s a journalist with a special interest in history and words and ideas — how ideas are passed and debated and become defining in generational time; how conversation becomes culture-shifting relationship. He attends to dynamics we don’t often take seriously enough: that every idea and discovery that changes the world begins with seeds planted over long stretches, and that this is always marked by passages that look like abject failure. Gal’s conversation with Krista offers fantastically useful insights into how our generation’s media that can scale things more rapidly than ever before can also inhibit the very ingredients that make for lasting transformation. At the same time, this lens on our world refreshes with its perspective on the way change happens, as opposed to mere disruption — the reality that our lives and actions below the radar hold the possibility of being more generative than we can measure.

Image by Jesse Zhang, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Gal Beckerman is the senior editor for books at The Atlantic. He has been a writer and editor for The New York Times Book Review, the Forward, and Columbia Journalism Review. In The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas, he tells stories from the last five centuries that have not come down in bold in history, but that incubated developments we later experience as defining — from France to Rome, from Moscow to Ghana to Tahrir Square.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: As any student of history knows, when time becomes history, very different dynamics come into focus than the ones that are at any moment screaming for attention. In our world of digital megaphones that privilege the immediate, it becomes harder to tell the difference between what feels urgent and is actually important, actually poised to shift the world on its axis. So I was excited when Gal Beckerman’s new book arrived.

The title itself intrigues and compels: The Quiet Before. He is a journalist with a special interest in history and words and ideas — how ideas are passed and debated and become defining in generational time; how conversation becomes culture-shifting relationship. He attends to dynamics we don’t often take seriously enough — that every idea and discovery that changes the world begins with seeds planted over long stretches and is always marked by passages that look like abject failure.

Gal Beckerman offers fantastically useful insights into how our generation’s media that can scale things more rapidly than ever before can also inhibit the very ingredients that make for lasting transformation. At the same time, this lens on our world refreshes, with its perspective on the way change happens, as opposed to mere disruption — the reality that our lives and actions below the radar hold the possibility of being more generative than we can measure.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Gal Beckerman leads The Atlantic’s daily book coverage and has been a writer and editor for the New York Times Book Review, the Forward, and Columbia Journalism Review. In The Quiet Before, he tells stories from the last five centuries that have not come down in bold, in history, but that incubated developments that we later experience as defining, from France to Rome, from Moscow to Ghana to Tahrir Square.

So, you know, I’m always interested in where the inquiries and passions that you hold, that you follow, were planted in your early life, in your childhood. And, you know, I see you as much as a historian as a journalist. And I know, for example, that you are a grandchild of Holocaust survivors. So I don’t know if that is a place you would start, or what else occurs to you when you think about this — the early seeds of what you’re working on now.

Gal Beckerman: Yeah, that’s fascinating to think about. [laughs] One finds interests and curiosities, and sometimes it’s difficult to sort of, to go deep enough beneath the surface to understand exactly where they’re emerging from. But I’ve always really been interested in the way that ideas sort of emerge and take over reality. And I suppose there is a link — maybe you’re pointing me to one — to try to understand something about my own grandparents’ experience, which was extremely formative for me, growing up, hearing those stories and knowing the trauma that they had been through. All four of my grandparents lost most of their family during the war, in a world that had sort of completely flipped on them in their lifetime. So there has always been a kind of an interest in understanding how that could be, how society changes in dramatic ways — how does it start from nothing and become part of the fabric of our reality?

Tippett: And I want to say to you, I know that a lot of what you have kind of gone into, what you might call case studies — different events, movements, the kind of pre-movements, the origins of phenomena that we see much later, full-blown, but we don’t remember the origins — and I know that your focus is really on kind of progressive change and revolutionary change, but what I think is valuable about this, too, is it’s also just — it’s about how change happens, right? It’s about how transformative change happens, good, bad, or ugly. And here we are, at a moment in time, in history, when we are reinventing our structures, our organizations, our societies, in good ways and bad. So I think that this intelligence, this kind of looking back at the long arc, is so valuable.

Beckerman: No, no; it feels necessary, to me, and I feel frustrated at times by the amnesia that we tend to have, societally, about what came before. There is a double meaning, maybe, to the book. The quiet before is also maybe the quiet before the internet. But there is this sense in which we believe that it’s impossible to imagine how people sort of came together en masse, or that an idea went viral —

Tippett: [laughs] Without social media.

Beckerman: Exactly, exactly. So one of the projects of this book was to say, like, what would it be, if we told these stories next to each other, if we had a book that started with letters before the scientific revolution and ended with Twitter and Black Lives Matter and tried to understand what were the threads that connected them, in terms of people need a means to communicate amongst themselves, and when you’re not in a room around a table — which is one option, but it’s not always an option that’s available when you want to sort of build something at scale — you need to have ways that you talk to each other. And my interest is in the medium, and the ways in which we need to understand them as tools.

And I think what you said was very correct — these are tools that could be used for terrible ends, for horrible ends, but —

Tippett: Well, it’s how transformation happens, and that can take many forms and have a lot of different kinds of character. I mean, so you often speak about what is needed for this kind of sustained, sustainable growth and development. I just — some of the notes I made — “a small group of committed people.” There needs to be a certain amount of “incubation” — “heat, closeness, intimacy.” And someplace you said there were a certain set of qualities that incubation gave these movements — really interesting list — patience, coherence, imagination, debate, focus, and control, and, as you said, a medium that provides incubation but can also give a movement these necessary ingredients for building to more lasting change.

You begin in France, in 1635, [laughs] with the Republic of Letters, a time in which the mechanics of everything was being examined. Why did you start there?

Beckerman: Well, I just, I really became fascinated with a particular story that I tell. But it gave me — which I can describe a little bit, but it gave — well, the story I tell is of a man named Peiresc, who was an aristocrat from Aix-en-Provence, who was part of this Republic of Letters. And the Republic of Letters, for people not familiar with it, was this fairly large group — I think there were maybe like 200 to 300 people involved in this at any given moment; it lasted for actually hundreds of years, but had its real flourishing in the 17th and into the 18th century. And it was a way for people who were — they called themselves natural philosophers, then, but all kinds of aristocrats and missionaries and people who had kind of an intellectual bent but were not part of universities and were doing all kinds of proto-scientific investigations on their own. They were just — the doctrines of the church were sort of beginning to break down, and it was an opportunity to look at the natural world and use the powers of observation to try to understand it.

But at the time that Peiresc was doing this work, it was still fairly dangerous work. One of his mentors at some point, and one of the men he most emulated, was Galileo. Peiresc wasn’t a character who wanted to sort of blow a trumpet and draw that much attention to himself. He wanted to carry out his scientific investigations in a quieter way, and so he used the medium of letters. Letters were incredibly effective, because they kind of flew — not only did they fly under the radar, but they were a way to have a sort of an ongoing conversation. That chapter, I call “Patience,” because there is a quality which you get out of writing letters back and forth, where it duplicates a conversation. It’s thoughts traveling through space, and you can kind of slowly influence people to a way of thinking, or share ideas in a way that — a book is one person’s kind of [laughs] announcement to the world, but this is a conversation, and he wanted the conversation.

And anyways, Peiresc had this idea that — he wanted to figure out the longitude of the Mediterranean Sea. All the maps, it seemed at the time, were completely off. They were from the time of Ptolemy. I mean, they were thousands of years — a thousand years old. But in order to do this, to accurately figure out longitude, what you needed was a lot of people in a few different geographic locations —

Tippett: Different places, right. [laughs]

Beckerman: Right, different places around the known world, all observing one astrological event at the same time and then marking the difference in time they saw it, and then that difference would equal longitude. So Peiresc recruited all kinds of far-flung missionaries and merchants, who were not natural philosophers, were not in this Republic of Letters, and he ended up finding that the Mediterranean was, in fact, about 500 miles shorter [laughs] than everyone had thought it was.

Tippett: You speak about him as a “connector” of Europe’s great minds and of the “quiet revolution” that was offered by the post. But also, I was really taken by these words of his: “The brevity of human life does not allow that one person alone is sufficient; it is necessary to adopt the observations of a good number of others from the past centuries and future ones to clarify that which fits better.”

On the one hand, I think, right, when you describe what had to be done to make certain kinds of observations that we could now do with very sophisticated instruments; and yet, what he says here remains true, [laughs] right? And in fact what they did, in that incredible, incredibly analog way, was one of the foundations on which we know how to do what we know how to do now.

Beckerman: It’s true. And I love that sentence from him, because, actually, that’s sort of science, as well, isn’t it?

Tippett: Yes, it’s science.

Beckerman: You take what people have observed in the past, and then you redo experiments, and you tweak them because they’re not accurate enough. And he sort of understood that. And what was fascinating was how he connected that to the letters. The letters, of course, weren’t a conversation with people in the past or people in the future, but it was the ongoingness and the, I guess, the appreciation for the incremental, which is something also that we’ve sort of lost today, [laughs] but the sense that knowledge happens in fits and starts, and people piece it together from their own particular angles that they’re coming from.

And that’s how they worked, in the Republic of Letters. That’s how they did their work. They would send each other data — they’d find sometimes artifacts, strange bones they’d discovered, or fossils, and sort of check each other. And this was sort of in the age before this was institutionalized. They were almost like the board of a scientific journal or something.

[music: “Sage the Hunter” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the journalist of ideas and history Gal Beckerman. We’re talking about his book The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas.

[music: “Sage the Hunter” by Blue Dot Sessions]

You also go to Manchester in 1839, and the subject is universal suffrage, which just feels so obvious, that it would come. [laughs] But this story is incredible, of, in 1839, 1.2 million signatures collected on pages that were pasted together that would be three miles long.

Beckerman: And what struck me so much about that story that this — and largely the petition, and the petition campaign, was the brainchild of the man who’s sort of the center of that chapter, Feargus O’Connor, who was a kind of a progressive politician at the time. And his message — he traveled all over England — his message was, pour your passion into the petition, into getting people to sign it, into having conversations around it.

This was also a moment, this interesting juncture between oral culture and literate culture where people are — somebody knocks on your door and starts to have a conversation with you about why you don’t have the right to vote, but it ends in an act of writing — of writing your name, of joining this community of people — and your identity changes. You become a part of the working class.

Tippett: And also — I mean, also, we need to say, and this is true of absolutely every story you tell, these are not unbroken arcs of beauty and triumph, right? So even with 1.2 million signatures, [laughs] on a piece of paper three miles long, it was ridiculed. And it’s mostly a history of failure for a long time.

But what you also, the story you also tell that feels to me — because I’m always thinking, what do we have to learn here, as we have to remake our world — as you said, it wasn’t just signing the page, it was having the conversations. And you said — and over time, that there were these small, local associations that coalesced, that became self-sustaining. And they were temperance societies, and they were collective newspaper reading clubs, and lectures and garden parties and singing and picnics. And it was that human force behind the signatures that moved, that shifted things.

Beckerman: Right. The petition became the sort of focal point around which a whole social world developed.

I think you made a really good point about the work involved in making it happen, because we have this critique today of the kind of “slacktivism,” right? And partly it’s that there is something about doing that work that, when it’s harder, when it’s not a click, but you have to actually go door to door and put in the time, that has these residual effects for a movement. It bonds people. It makes you feel more identified. It gives you a sense of connection and purpose that’s because you’ve put in the sweat, you’ve put in the time. So that it had its own role to play, actually — the hardship of it.

Tippett: The hardship, yeah. I mean — I feel like we could spend a couple of hours just going through every chapter. Then we go to Florence in 1913, the Florentine Futurists. I have to tell you, just my favorite line in that is Mina Loy, who’s one of your characters. And she says, “Personally I am getting very young” … [laughs]

Beckerman: [laughs] Yeah, I love that.

Tippett: … which is actually something I’m kind of feeling like this right now, in our tortured world. And I think that, also, is somehow part of the story of not just being part of something that changes the world, but how this kind of depth of engagement not just changes, but energizes, enlivens the people who do it even when they are facing one setback after the other; sometimes very grave and dangerous setbacks.

Beckerman: Right.

Tippett: And all of these stories, I mean, one thing is these are mostly stories kind of animated by people whose names we don’t remember, right? It’s not the person who became famous at the apex or when things kind of — when it was not the quiet before, but the noisy — [laughs] right? — the noisy emergence into a kind of mainstream civilizational attention, and years and years and years passing, but where something is happening.

Beckerman: Yes. And I think the thing that’s happening, and the thread between all of these, and I don’t — I mean, it’s the thing that fascinates me most, is they’re talking. It’s conversation. And I mention in the book Jürgen Habermas, the German philosopher who sort of made a real sort of fetish of [laughs] the role of conversation and of talking and of deliberation in sort of the building of democratic society, of Western civilization. And that’s what I see in those moments in the quiet before. I see people having conversation. And it’s through the friction of minds interacting through speech, through talking, through sharing ideas, that is the only way that a newness sort of enters the world.

And so it feels funny, in a moment where there’s so much noise and talk and chatter [laughs] around us, to be arguing for more talking and conversation, but in some ways, for me, it’s the — like, there’s a distinction between what does it mean to be social — and there is a concept of being social where you go to a cocktail party, and it’s really loud, and somebody makes a joke and everyone kind of turns in that direction, and then you have a snippet of conversation with somebody else, but you can hardly hear it, and then you get pulled into something else, and pulled out of that — and then at the end of the day, you come home from that party, and you’re taking off your shoes, and you think, I didn’t actually talk to anybody. Like, that was — I think, what was that? I didn’t connect with anybody.

Tippett: And that’s what social media is like.

Beckerman: Right, and so to me, that’s the “social” of social media. But that isn’t the only model of what it means to be social.

Tippett: Yeah, there’s a phrase you have in there somewhere: slow, communal discovery.

So I believe it’s true to say that you were initially motivated to start investigating this as you watched Tahrir Square unfold — the Arab Spring, 2011, is that right? Because what happened there, in terms of a social pivot, a social movement that kind of riveted the world, was a very different model from all these things we’ve been talking about, because of this power of social media.

Beckerman: Well, I think it was a time where we talked about “Twitter revolutions” and that there were people who were extremely bullish on the notion that all you needed — in fact, the main character of the chapter I have about the Arab Spring, Wael Ghonim, said, That’s it — all you need for a revolution is social media, that that’s the secret ingredient.

And I think what actually happened is it did provide this incredible tool for getting people into the streets. That viral quality was incredibly helpful in speeding things up. So speed and scale — I don’t think we can argue with speed and scale [laughs] as qualities that the internet has and that social media in particular has. And so you had a lot of disgruntlement among a certain class of people in Egypt, and in a lot of different Arab societies, but I looked specifically at Egypt, and social media sort of allowed that match to be lit in a pretty dramatic way and got people into the streets.

The problem, as I sort of even intuited it then, although it became clearer to me as I saw a lot of these revolutions almost uniformly lead to even more repressive situations in those countries, as is the case in Egypt, is that the tool that actually allows you to go out into the — if we’re looking at these communications tools as having certain capabilities, right? — that a bullhorn, which is a wonderful tool; like, a bullhorn is very effective. But if you begin — if you start to believe that a bullhorn is the only thing that you need, and if you contort your movement so that it’s all about making sure that you can hold onto the bullhorn and use the bullhorn, you’re denying yourself some really important tools. And the coalition that came together in Tahrir Square was incredible and new, and what they needed to do was sort of turn themselves into a real political opposition — which was going to be hard in any circumstance, especially because they were mostly up against the Muslim Brotherhood, who had spent decades sort of developing their hierarchy and their identity as an organization. But this group of radicals who wanted to democratize Egyptian society, they said, Hey, this tool, this bullhorn really worked well for us; that’s the thing. And they just kept trying to use it again and again and again and didn’t give themselves the opportunity to develop the other tools that they would need to actually become a real opposition.

Tippett: Have something that was sustained and robust. Was this Mahmoud Salem, said that what social media gave the revolution — the aspect it seemed stuck on and could never outgrow — was a spirit for destruction, eventually? It didn’t give it the tools for the building, the digging in. [laughs] And then Wael Ghonim, you write, became — who was the avatar of the Arab Spring, became a social media reformer.

You know, something — I’ve wanted to talk to somebody about this. For me, the Arab Spring — because I also, like you, look at the long sweep of history and what happens — what we see differently when time becomes history, you know. My suspicion is that even though it had this very different trajectory, this dramatic trajectory of scaling and then seeming to be completely deflated, that seeds were planted, that there — and I do hear this from time to time, when I speak with people who know that region. So now it’s like the quiet before has come after the — [laughs] the dramatic revolution that would’ve been.

So, for example, the French Revolution, which we think of as a successful revolution and forget that — I mean, I went back and looked at the timeline, just because I was going to be — it was in 1789 that the Bastille gets stormed. The French Republic is proclaimed in 1792. In 1793, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette are executed. Napoleon sides with the revolutionaries, but by 1804, he has crowned himself emperor, right?

Beckerman: Right, we forget the whole Reign of Terror part. [laughs]

Tippett: And he reinstates Louis XVI’s brother as king! When is that, 25 years after what we celebrate as the French Revolution?

We see, also, at this remove, that something took hold that was transformative over time. And I just — my suspicion, and you could call me hopeful, but I think the way these things work is that something happened in 2011, and in 30 years we’re going to have a very different view of it than we do right now. I’m just curious what you think about that.

Beckerman: No, I agree, if only for one thing, which is it brings possibility into the world. People can’t sort of strive for a reality until they can begin to imagine it, right? And to imagine it, they need to see some indication that it could exist, might exist. And so the fact that this level of protest — that they brought Mubarak down; and if it happened, it can happen again. And I think that that formulation in people’s minds — if it happened, it can happen again, and maybe this time it could be different, maybe this time people will be more prepared, maybe there is a quiet before that’s happening now. The political activists in Egypt are an incredibly embattled group of people right now. But I end that chapter with a man named Alaa, who is probably the most sort of well-respected of the activists. And he’s — it was him talking about the lessons of not being on social media; [laughs] that these things do come in cycles, and there are lessons to be learned. And I think — I think that one of the lessons is you have to build a movement so that when the explosive moment happens, when the viral moment happens, when you have the instant where you can have an opportunity to recruit a mass of people to your idea, that you’re ready for it, that you’ve done that hard work of actually hammering out what you want and who you want to be.

Tippett: But also, that’s human relational work, right? It’s that — what was that language of the physical — right? — “a culture spinning out from a central, intimate act, carried out one person at a time.”

Beckerman: I really believe that’s true.

[music: “Haena” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Gal Beckerman.

[music: “Haena” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the journalist Gal Beckerman. In his new book, The Quiet Before, he revisits dynamics across five centuries that tell a story we don’t often take seriously enough: how every idea that has changed the world began with seeds planted over long, fitful stretches.

The Civil Rights Movement, the Southern Freedom Movement, is a vivid example in living memory. We can trace its origins in decades or in centuries that preceded what were later seen as history-making triumphs, like the March on Washington or Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches heard across the globe. The final chapter in The Quiet Before is called “The Names,” and it is a reflection on the post-George Floyd era. It throws into relief the way the young and still evolving model of movement that is Black Lives Matter has followed this pattern, only fitfully seen and heard and heeded in dominant culture even as it was and is remaking lives and the world.

Somewhere you said, in your chapter called “The Names,” “By early 2020, Black Lives Matter was talked about in the past tense, [when] it was talked about at all.” And that’s in terms of the official narrative and powerful media on every side of the political spectrum. And then, when George Floyd was murdered, and in the context of the year of 2020 and that — it was very much alive, Black Lives Matter. But it didn’t look like a movement that we’d been trained to see, right? And there it was. And it had a fullness to it. And it had depth to it.

Beckerman: And it had objectives that people might not have been aware of [laughs] until they really were, like reforming the police. I think one of the things I tried to do in that chapter was take the slightly longer view of the last 10 years, or not even quite 10 years, but talk to activists who were involved in what was sort of the first wave of Black Lives Matter, which was started around Trayvon Martin’s killing, and through Ferguson, and really up until 2016, when a certain presidential candidate sort of sucked all the oxygen [laughs] out of social media. But there was — this was this kind of long moment where there was this series of horrific videos and moments of police brutality that allowed the movement to kind of emerge in people’s consciousness and then sort of grab attention, then kind of flare out, then grab attention, then flare out, grab attention and flare out.

And I started talking to folks, actually before 2020 — I’d actually written a version of that chapter that I had finished at the end of 2019, thinking that I was writing a kind of an obituary for Black Lives Matter. But when I began to talk to these activists, they said, No, actually, we learned a lot from that moment. And one of the things they learned was sort of the central lesson that I learned in my book, looking at the past, which is we need to be prepared for those moments. And to be prepared for those moments means hunkering down now, and that movements have a cycle.

A lot of the — I’m not talking about maybe some of the younger activists that just sort of run out into the streets as soon as there’s something to run out in the streets for, but the people who were really organizers in various communities — they understood that they needed to get off social media. I look at one group called The Dream Defenders, in Miami, who actually did this. They did something called a blackout, where they just completely got off and then started talking to people in their communities. And one of the things that mattered to them as a group was defunding the police. And what they discovered when they started talking to people, going door to door, having conversations, is that the majority of people did not want to defund the police. [laughs]

Tippett: It’s more complicated than that.

Beckerman: Yeah, that it was more complicated, that they were worried what that would mean, they didn’t really understand what the concept was, that the concept was about not blindly funding police departments in this country to the tune that they’re usually funded, but actually moving some of that money away to, or funneling some of that money into other social services and maybe having a social worker respond to a situation on the street, as opposed to a police officer — that there are actually very nuanced and interesting proposals that were bubbling, but people didn’t understand them.

And the idea of getting off social media was like, this keeps us from just relying on this slogan —

Tippett: It is hard to do nuance on social media, right? That’s what it doesn’t do well.

Beckerman: Exactly. Exactly. And actually, through these conversations and through actually — much like the petitioners in the 1830s, going around and actually trying to convince people of a position or understanding where they’re coming from, those are those acts of conversation that I think made those groups a lot more sophisticated.

And at the height of that sort of earlier phase of Black Lives Matter, 2013 to ’16, the people who — in newspapers and magazines were literally making lists of the most influential activists in the movement based on their follower accounts on Twitter.

Tippett: Right, and that was so controversial inside.

Beckerman: And when you do that — let’s say you’re an organizer just sort of on the ground, trying to have influence in a local city council race because you know that this person could tip the balance and actually enact local laws that will affect communities of color that you care about, that you’re trying to advocate on the part of, and then you see that the people who are getting attention are the ones who knew how to make Twitter work for them and have the kind of voice that Twitter wants and the — it can be a very demoralizing thing and make you think that that’s where you need to shift your attention to.

Tippett: So I think one of the themes in your writing and one thing that’s so great about reading this is that our imaginations are very, are kind of paralyzed [laughs] by the world of social media, by how we see things happen now — even by a phrase like “going viral,” or failing to go viral, being followed or being liked, or not. Whereas in previous eras, in some places, things were done [in] private, because that’s all you had, we now have a world where everybody is handed the megaphone, essentially.

Beckerman: Yeah, and one of the things — I don’t want people to read this and think the internet is fundamentally horrible and we need to just all go use typewriters. It’s actually just a plea for some self-awareness about the way that we use the various tools that are available to us online. And somehow, when it comes to movements or when it comes to trying to put a new idea into the world and convince other people of that idea, we still are attached to this idea of virality as the thing that matters most. We still believe that —

Tippett: Scaling quickly.

Beckerman: Yeah, if we — exactly; scaling quickly, if we just put up a good Facebook post, if we get a lot of people into our group online, if our tweet goes viral, like, we’re starting something, something real. And that’s sort of what I’m pushing against, is to — and that’s what the Black Lives Matter activists who I got to know really, really understood, is that this has its function. It’s one thing. It’s one tool in the toolbox.

I keep returning to this notion of tools, but I think that is the way we need to think about the media that we use and that we need to be careful about when we actually pick it up, and understand that there are other tools in that toolbox. And some of them might feel counterintuitive, because it’s not what’s particularly popular at the moment, but they are very effective in this process of development and incubation.

Tippett: And I would just kind of paraphrase it that way — let the context of how we use the tools be what we can know about how the world actually works, how change actually happens, that is generative and sustainable. And that’s kind of the offering you’re making.

I loved reading — I think this is an article you wrote — about reading parties [laughs] in 2020, and 2020 silent reading parties, which you both wrote about and also took part in — quarantine book club, borderless book club. You wrote about this Hannah Arendt reading circle, reading about — reading The Human Condition, which is just such a phenomenal, eternally insightful book. And you work with this image that somebody gave you who’s leading one of the reading circles. And he said, “When you have a group of people sitting around a table talking, the table is what makes them a group.”

Beckerman: Yeah, I love that.

Tippett: “And if you take the table away, they’re just individuals, they’re not connected.”

But I think you ask, is Zoom our table?

Beckerman: Well, in that moment, [laughs] it certainly felt like it. Arendt’s image of the table and the people sitting around the table, and then the table disappearing, and who are they, is really a moving one to me, and it’s one that inspires sort of my search in this book, in a way, because I wanted to understand sort of what those tables are, for us, as people. I’m looking at the specific context of how change begins, but it seems to me that the table has an important role — the physical table, the space that’s bringing people together into conversation. And her point was, once the table is gone, who are we? And I think she’s pointing to a medium there, in a way. You need an avenue through which you come together. And I feel like when I started to look at letters, when I started to look at petitions and all these examples that we talked about, I sort of found those tables.

Tippett: The tables were always in the story, right.

Beckerman: Yeah, there’s always something that is bringing people together in that way. And can we find those tables online today? Are people doing that? For sure. I think my objective, if there’s — [laughs] if there’s any advocacy in this book, it’s to search for them and understand their importance to human development and progress.

Tippett: Well, but I also feel like you’re pointing us back to the actual tables, right?

Beckerman: Yeah, that too. [laughs]

Tippett: You’re saying, let’s not — let’s do both, but let’s not forget that we still have tables to sit around …

Beckerman: We still have actual tables.

Tippett: … and that somehow, that is an absolutely essential thing that happens when things take off in a long-term way.

Beckerman: For sure.

[music: “Funk and Flash” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the journalist of ideas and history Gal Beckerman.

[music: “Funk and Flash” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So I know we’re speaking as this book, The Quiet Before, is just entering the world, but I understand that you met over Zoom with an eighth-grade social studies class in New York City.

Beckerman: [laughs] I did.

Tippett: And they had read, I guess, the introduction. And I’m so curious to hear — these are young humans who’ve grown up with media as we know it now; I’m just so curious about what their questions and observations were and how they perhaps were different from yours, and what you learned from that exchange.

Beckerman: They were wonderful, first of all. They were so willing and eager to sort of understand. They were studying social movements, so I was sort of coming in to talk to them from a place of this expertise gained from the book. And they — the first thing that was funny was that they — it’s very hard for them to imagine doing something in an analog world.

Tippett: [laughs] Right, right.

Beckerman: [laughs] They are so — it’s so part of the fabric of their reality that how could a meme not be involved when you’re talking about social movements? Isn’t that what a social movement is? [laughs]

But I have to say, their questions were kind of more searching than anything else. They wanted to understand sort of how you recreate the thing that I’m talking about. Like, how do you step away? They were looking for prescriptions, I think, which I found to be hopeful, because they — even if it was difficult for them to sort of imagine what change could mean without this particular tool they’ve become very familiar with that they do everything on, they still were — they said, well, how do you do it? Like, how do you find the quiet? What’s that process like? [laughs] And each kind of asking it in different ways, but it did make me sort of think that they had the capacity, [laughs] if they were asking the question.

Tippett: If you look around our world now, where do you — I mean, obviously there’s an inherent contradiction in this question, because part of what you’re doing is talking about things that can only be seen decades later, right? [laughs] And that’s kind of the point of it. But what are you observing now that might be something that someone 30 years from now looks at and says, Oh, there’s a beginning; there’s a quiet beginning?

Beckerman: I mean, it’s not even so quiet, but I have to say one of the things lately that I’ve been aware of, that I think we’ve all been aware of to some extent, is the activism around climate change, and particularly young people. And I find it — I find it very hopeful. You know, some of the conversations that I’ve heard recently are a real rejection of the performativeness of [laughs] not just politicians’ actions, but of anybody who is on social media kind of making a big deal about something they’re doing. They’re interested in getting back to basics and figuring out alternatives. And there is a sense that the way to do that is on a much smaller scale. And to me, that’s hopeful. I see similar conversations happening around police reform, particularly among the activists that I spoke to.

Those are kind of two areas that are demanding a lot of imagination. If you want to rethink how we’re going to approach this crisis of climate change, it seems to me the way that we’ve been doing things or the way we’ve imagined we can change things is not working. So [laughs] the avenues for picturing what could work — we have to establish those. We have to create the spaces where that can occur. And I feel like there is — that young people are in some ways more conscious of — at least the ones that I’ve heard talk about these issues, they’re conscious of the way that something like social media sort of distorts what they do. And they have the awareness to push it away or, at least, keep it at arm’s length.

Tippett: And use it as a tool, but see its limitations.

So I want to ask you a question just in light of all these things we’ve been discussing. What — just kind of right now, this week, today, what makes you despair, and where are you finding hope?

Beckerman: Give me one second. [laughs]

Tippett: That’s allowed. [laughs]

Beckerman: I think despair is easier for me [laughs] to answer right away. I have a 12-year-old and a 9-year-old, and I worry about the role that technology has in their lives and the way that they’re losing a capacity to focus and sustain attention in a way that I think is important, not just to do things like read books, which matter to me a lot, [laughs] but to do really anything that that demands hard work, which I know that they’re going to want to do. So I find myself despairing a lot about what it means that their brains have sort of contorted to these devices that they find themselves on too much. And COVID has obviously exacerbated this to an extraordinary degree.

I find hope, though, in the knowledge that the things that bring us joy haven’t changed that much. [laughs] It’s still — and in some ways, we’ve been reminded of them in this moment. I miss my friends. I miss having social contact in a way that’s been very hard to find over the last two years, even as COVID has waxed and waned; I’ve felt pretty isolated.

Tippett: Not enough tables in your life.

Beckerman: Not enough tables in my life. I just said this morning to a friend, I said, I haven’t been in a bar in a long time. And I don’t know that I really need a — like, I wouldn’t think that I would need a bar, but there is a particular kind of space that opens up when you’re sitting and you’re having a beer, and then maybe a second beer, and you’re — it is that table that’s bringing you together. And so what brings me hope, I guess — I mean, that could be a despairing thought: I need the bar. But I’m hopeful in that I haven’t lost — and I don’t think humanity, [laughs] if I can speak that broadly, has lost that really deep need, in spite of the fact that we’ve been deprived in all these ways. And I find that hopeful, because it means that there are these essential qualities of life that we need, and one of them is being with people, and that in some ways we’ve been given this gift — I mean, at a horrible price, but we’ve been given this gift of being reminded of that.

[music: “Lamplist” by Blue Dot Sessions]

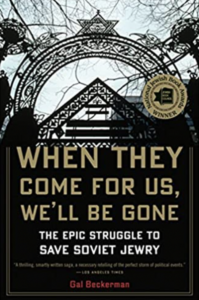

Tippett: Gal Beckerman is the senior editor for books at The Atlantic. His new book is The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas. He’s also the author of When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry.

[music: “Lamplist” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.