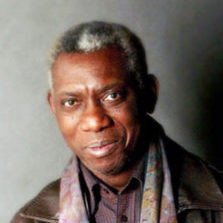

Yusef Komunyakaa

Praising Dark Places

Is the light a comfort and the night disturbing? Yusef Komunyakaa explores the life and brilliance of what’s in shadow and darkness.

We’re pleased to offer Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Yusef Komunyakaa was born in Bogalusa, Louisiana. The son of a carpenter, Komunyakaa has said that he was first alerted to the power of language through his grandparents, who were church people: “the sound of the Old Testament informed the cadences of their speech,” Komunyakaa has stated. “It was my first introduction to poetry.” He has taught at numerous institutions including University of New Orleans, Indiana University, and Princeton University. He is a senior faculty member in the NYU Creative Writing Program.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and early in my career in conflict resolution, I think I used to hope that I could bring everybody in a conflict resolution to the same point of analysis about what was going on. But one of the things I began to learn very quickly was that ultimately, in resolving a conflict with a group of people, you’re hoping that a group of people can get to the stage of holding ambivalences and ambiguities with each other, where they can begin to look at things from a different point of view and they can say: We don’t know what to do with this, and we’re not sure; this didn’t work before, but we’re going to try something different in the future. That ambiguity, and the capacity to hold that in public with each other, is one of the arts of being human.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

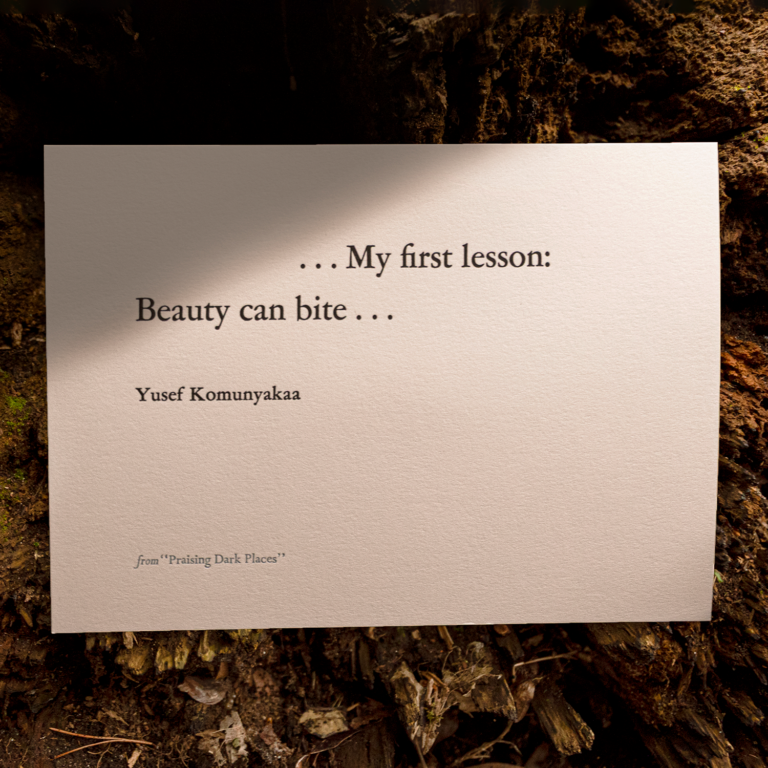

“Praising Dark Places” by Yusef Komunyakaa:

“If an old board laid out in a field

Or backyard for a week,

I’d lift it up with a finger,

A tip of a stick.

Once I found a scorpion

Crimson as a hibernating crawfish

As if a rainbow edged underneath;

Centipedes & unnameable

Insects sank into loam

With a flutter. My first lesson:

Beauty can bite. I wanted

To touch scarlet pincers—

Warriors that never zapped

Their own kind, crowded into

A city cut off from the penalty

Of sunlight. The whole rotting

Determinism just an inch beneath

The soil. Into the darkness

Of opposites, like those racial

Fears of the night, I am drawn again,

To conception & birth. Roots of ivy

& farkleberry can hold a board down

To the ground. In this cellular dirt

& calligraphy of excrement,

Light is a god-headed

Law & weapon.”

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

The first thing about this brilliant poem is that the earliest part of it is a description of a boy, I think, picking up a piece of board to see what’s underneath it. And you see his amazement at the color, the movement of insects going down into the earth, the different “[c]entipedes and unnameable / Insects” sinking into loam. And he gets bitten, and he wants to touch, and he’s fascinated that they don’t kill each other, but nonetheless, they do bite him.

And the second thing about this poem is the way that the voice changes partway through it and begins to reflect on what is happening in the context of light coming into this part of the earth that was covered over by a board, where darkness was the natural way within which these insects seem to flourish; that light in this context is some kind of interruption, that it’s something that they scuttle away from.

So partly, I always think that this poem is responding to the curiosity in poetry, in public language, in religion: is light always a metaphor for good, and is dark always a metaphor for difficulty? And this poem is exploring that through the curiosity of a child and then the adult reflections of that grown-up child.

[music: “Levander Crest” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Years ago, I was at this big meeting; I was speaking at it. It was a religious meeting. And the people there were singing a hymn, kind of like a contemporary Christian chorus. And the chorus of this song said: “Jesus, make me whiter. Jesus, make me whiter. Jesus, make me whiter than the snow.” And there were a few thousand people singing this, enthusiastically. And I find it difficult to join in in choruses like that anyway, but this one just seemed to me to be so unaware of what was being repeated: “Jesus, make me whiter.” How, in this planet, with the history that this planet has and the contemporary stories of this planet — how can you say that? I was so disturbed.

And I suppose I began noticing from then, where else is it that the idea of white or light is a metaphor for something good, and the idea that dark or black, that that can be a metaphor for difficulty? And it’s so many places, in so many old poetries. And this poetry has a profound intelligence, looking at the curiosity of a child to bring light, and the way that the light, therefore, is an interruption to the lives of these insects, and then, within the context of that, how he begins to reflect on: what do I think about light and dark as metaphors?

[music: “Dirty Wallpaper” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The first thing that comes to my mind when I think of the line “Beauty can bite” is that he’s thinking about how perhaps he might have reached down, out of curiosity, to a scorpion and been bitten back, or almost been bitten back by it. So: beauty can bite. But also, he is lifting something up and exposing these insects to something that they don’t want. So maybe he’s the bite.

And in the context of all of this he’s beginning to see himself through all kinds of ambivalences. And that’s the brilliance of this poem. This poem is not saying: Everybody’s got it wrong, it’s exactly the other way around. This poem is saying: We live in a situation of profound ambivalence. What do you need? What happens for you? How do we go about this? It’s an invitation into magnificent subtlety and magnificent ambivalence. It is saying the world doesn’t operate in this kind of a way, in a binary way. He is saying over and over again, in this poem: Pay attention. Look. Notice from the earth.

It starts in the field, it goes into a bit of abstract philosophical speculation, and then it ends, back in the earth: “Roots of ivy / & farkleberry can hold a board down / To the ground.” And then he goes even further: “In this cellular dirt / & calligraphy of excrement, / Light is a god-headed / Law & weapon.” Whose weapon? Whose law? Whose god? In all of this he’s introducing brilliant ambivalence to the question of, who gets to say light’s great, and darkness isn’t? Who gets to say that one thing is only one thing?

Toward the end of the poem, Yusef Komunyakaa has a couple of lines where he lifts the locale of this poem and suddenly begins to look at the whole world: “Into the darkness / of opposites, like those racial / Fears of the night, I am drawn again / To conception & birth.” What’s he doing in these few words, thinking about: do conceptions happen in the light of the day? How much growth happens in the dark? How much dark is a repository for racial fears being projected onto other people? In these couple of lines, he is looking at the earth. This is the voice of a man, now, not the voice of a child. He’s looking at the earth and reflecting on how the earth calls to mind rituals, and considerations of questions to do with birth, with conception, and also with death and protection. What’s he saying about the nature of trying to fight for your own life?

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

In this poem, Yusef Komunyakaa is posing a philosophical question about how is it that we live in the world, and what metaphors are good enough for the way that we talk about good and evil? And he is saying: Look. Observe. Be educated by the earth, what you think works as metaphor for good and for evil. Pay attention as to whether that works for other living beings, too, and adjust your language accordingly. Be educated by the scorpion. Be educated by the crimson insect or the way that a rainbow creeps underneath the board. Be educated by all of this. Displace yourself from assuming that your curiosity is the center point of analysis, and find a way to listen and learn from the intelligence of the earth and the intelligence of praising dark places.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Praising Dark Places” by Yusef Komunyakaa:

“If an old board laid out in a field

Or backyard for a week,

I’d lift it up with a finger,

A tip of a stick.

Once I found a scorpion

Crimson as a hibernating crawfish

As if a rainbow edged underneath;

Centipedes & unnameable

Insects sank into loam

With a flutter. My first lesson:

Beauty can bite. I wanted

To touch scarlet pincers—

Warriors that never zapped

Their own kind, crowded into

A city cut off from the penalty

Of sunlight. The whole rotting

Determinism just an inch beneath

The soil. Into the darkness

Of opposites, like those racial

Fears of the night, I am drawn again,

To conception & birth. Roots of ivy

& farkleberry can hold a board down

To the ground. In this cellular dirt

& calligraphy of excrement,

Light is a god-headed

Law & weapon.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

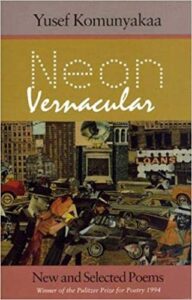

Chris Heagle: “Praising Dark Places” comes from Yusef Komunyakaa’s book Neon Vernacular. Thank you to Wesleyan University Press, who gave us permission to use Yusef’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections