Isabel Wilkerson

“We all know in our bones that things are harder than they have to be.”

In this rich, expansive, and warm conversation between friends, Krista draws out the heart for humanity behind Isabel Wilkerson’s eye on histories we are only now communally learning to tell — her devotion to understanding not merely who we have been, but who we can be. Her most recent offering of fresh insight to our life together brings “caste” into the light — a recurrent, instinctive pattern of human societies across the centuries, though far more malignant in some times and places. Caste is a ranking of human value that works more like a pathogen than a belief system — more like the reflexive grammar of our sentences than our choices of words. In the American context, Isabel Wilkerson says race is the skin, but “caste is the bones.” And this shift away from centering race as a focus of analysis actually helps us understand why race and racism continue to shape-shift and regenerate, every best intention and effort and law notwithstanding. But beginning to see caste also gives us fresh eyes and hearts for imagining where to begin, and how to persist, in order finally to shift that.

Isabel and Krista spoke in Seattle before a packed house at Benaroya Hall, at the invitation of Seattle Arts & Lectures.

[Content Advisory: Beginning at 21:16, there is a discussion of Nazi terminology and a quotation from Hitler with an epithet that is offensive and painful. We chose to include this language to illustrate the heinous nature of the history being discussed and Hitler’s admiration for it.]

Image by Danyang Ma, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Isabel Wilkerson won a Pulitzer Prize while reporting for the New York Times. Her first book, The Warmth of Other Suns, brought the underreported story of the Great Migration of the 20th century into the light, and she published her best-selling book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents in August 2020. Among many honors, she was awarded the National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: Here’s what I so deeply appreciate about Isabel Wilkerson’s voice: she trains an unflinching eye on histories we are only now communally learning to tell, and she holds that with a huge heart for humanity — a devotion to understanding not merely who we have been, but who we can be. Her most recent offering revolves around “caste” — a recurrent pattern of human societies across the centuries, though far more malignant in some times and places than in others. Caste is nothing more and nothing less than a ranking of human value: who matters the most, and who matters less. It is communal infrastructure that becomes internalized and perpetuated at every level along the hierarchies that result. It is like grammar, figuring absolutely reflexively yet guidingly into our sentences, the words and structures of our being. In the American context, as Isabel Wilkerson proposes, this helps us understand why race and racism continue to shape-shift and regenerate, every best intention and effort and law notwithstanding. But beginning to see caste also gives us fresh eyes and hearts for imagining where to begin and how to persist in order, finally, to shift that.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Isabel Wilkerson won a Pulitzer Prize while reporting for The New York Times. Her first book, The Warmth of Other Suns, brought the underreported story of the Great Migration of the 20th Century into the light, and she published her best-selling book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents in August 2020.

We spoke in Seattle before a packed house at Benaroya Hall, at the invitation of Seattle Arts & Lectures.

[audience applause]

Tippett: Well, we’re not used to that anymore, are we? How amazing is it to be together? I’m so happy to be here with my friend, Isabel. So first of all, just thank you, Seattle Arts & Lectures. Thank you for all the people who’ve made this possible. I first interviewed — I interviewed Isabel once before when we first met in October 2016. A few lifetimes ago. And I interviewed her about The Warmth of Other Suns. But interestingly, when I went back and was looking at the transcript, you were using the word “caste.” I think this book was incubating in you.

And I don’t become friends with everyone I interview, but Isabel and I have become friends and we actually spent some time together in Berlin last summer. And maybe we’ll talk about that, I don’t know. So I want to say, speaking as somebody who is your friend as well as someone who’s engaged with your work, you are a fierce journalist and a brilliant analyzer, and wordsmith. But what I believe really drives you — my experience of what drives you — is this passion you have at looking at the intersection of the vagaries of the human heart, the human condition, and our life together at a communal and species level.

So there’s a place in the book where, this is just a clause, “Moving about the world as a living, breathing, caste experiment myself.”

Isabel Wilkerson: Yeah.

Tippett: So you have the word “origins” in the title of the book. I think I wonder when I read that, forming that sentence, that thought, “Moving about the world as a living, breathing, caste experiment myself.” Do you look back at say, your father, who is one of the last Tuskegee Airmen, or your mother, or the world of your childhood, do you see things in that light or would you articulate things that you might not have articulated in the same way before?

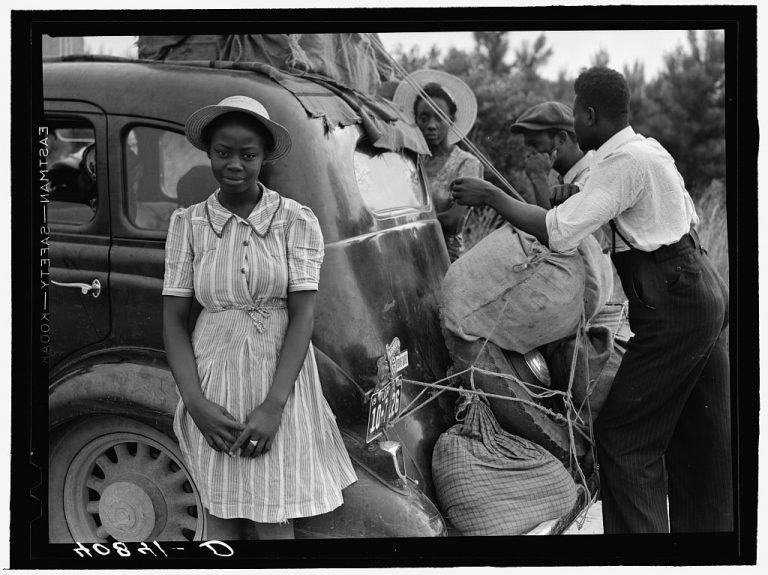

Wilkerson: I think that you made mention of how I was using “caste” with The Warmth of The Suns. I came to the recognition that the only way to describe what my parents and my grandparents had experienced was this stratification, this framework, this hierarchy that they could not escape unless they left or at least sought to leave.

Tippett: And your parents were both part of the Great Migration…

Wilkerson: Yes.

Tippett: … from the south to Washington, D.C.

Wilkerson: Exactly. But another way of looking at it is that I was raised by people who had survived Jim Crow, which is the term that we use for what I call the “caste system.” And what anthropologists who studied the Jim Crow South called it. And I’m thinking about my father, who, as you mentioned, was a Tuskegee airman. And after the war, these men, who had been among the finest pilots that our country had ever produced, were not permitted to work in the field that they so loved. They were not permitted, they could not get hired as pilots. And so each of them, my father included, had to go back and re-figure what were they going to do. Try to remake themselves. Abandon what they had loved so much and what they were so good at. And so a lot of them went back. Some of them became dentists, and they went back and did other things. And my father went back and he got another degree in civil engineering, which means that he became literally the builder of bridges. And so I am literally the daughter of a builder of bridges, and that is how I choose to move about in the world, and it animates my work, and it’s what’s beneath everything that I write.

[audience applause]

Tippett: So I know that you love metaphors. [laughs]

Wilkerson: [laughs] I do, that comes from my mother.

Tippett: Does it?

Wilkerson: Yes.

Tippett: And one of the things that is such a gift of this book, in my mind — yes, it’s about caste, a ranking of human value and underlying infrastructure of a society’s divisions. What you also do — I heard just before we came out here, Jerry Calhoun, who’s brought some fellows here, who’s a sponsor of this program, talk about “opening apertures.” And I think your metaphors open new apertures for us to consider how all the — and us, I mean America, this country — all the ways that race and racism have been grappled with from time to time, and yet somehow we have not been able to get to the root of what we’re trying to work with.

And I think these metaphors and these images that you give as the book unfolds, they take your hand and they’re new ways in to help us imagine, I would say, to open hearts and intellect and imagination about what that work is. And so I would like to just walk through some of them because I just think they’re incredibly helpful. And the first one is: it is like a toxin in the permafrost, a pathogen.

Wilkerson: Yes. [laughs] There was a really brief mention on the radio back in the summer of 2016, so brief that if I hadn’t been paying attention I would’ve missed it. And it happened to be talking about how in the Siberian Tundra. There had been thawing of the permafrost. And it had uncovered, as a result of the thawing of the permafrost, these ancient, these reindeer carcasses that had resurfaced, and they had resurfaced from the time of World War II. So that’s also a very meaningful point in history. 1941 is when anthrax had overtaken the reindeer population of the Siberian Tundra and that this is the effect of climate change. All of it was coming together. And there was this reemergence of this toxin in the summer of 2016.

And I heard this fragment of a news brief, and that set me on this journey. At that point, I wasn’t sure. I was still resisting the idea, should I do this book? Should I do something else on it? And that set me on a path. I just felt: this is something. I didn’t know what it was. It took weeks and weeks and weeks to do the research and the reporting to flesh that out, to turn it into a chapter in this book. But I knew that it was going to open with that from the moment I heard it.

Tippett: What is so valuable about that image is it something that can go under…

Wilkerson: Yes.

Tippett: …it can hibernate, it can go into hibernation. But it can also resurface and it can mutate.

Wilkerson: It can mutate, and that it’s ever-present. And we fool ourselves into thinking that it can ever, truly, it can be vanquished in the ways that we might think it could be vanquished. That once you assume that it’s vanquished and you don’t have to think about it, that means that you are now more susceptible to falling prey to it because you thought it was buried and you thought you would never have to worry about it again. You thought it was taken care of. It was buried in the permafrost and it thawed and resurfaced again in the summer of 2016.

Tippett: Okay. Second metaphor: it’s like an old house.

Wilkerson: Yes.

Tippett: And you love old houses.

Wilkerson: Yes.

Tippett: Is that the first image that came to you? Was that the first metaphor you were working with? Because I think we talked about that way back in 2016.

Wilkerson: Yeah. I make mention of the fact that there was this bulge in the ceiling in a bedroom, and it actually was happening, it was real. All of this is real. And I was reminded that we often think, that we’d like to think that you fix something in an old house and that you’re done. But if you live in an old house, you know that it’s never done. [audience laughs] It is never done. And as soon as you fix one thing, then something else goes wrong. These systems need constant monitoring, vigilance, attention, repair, sometimes overhaul. You never assume that you get a new hot water heater and you’ll never have to worry about it ever again. You know that’s not true. [audience laughs] So I thought that this was something that…

Tippett: Clearly a lot of old house owners in this room.

Wilkerson: A lot of old house owners. [laughter] And I thought that was a really universal way of entering an understanding about our country. If we think of our country as being like an old house and we know that the work is never done, and we wouldn’t assume that the work was ever done. You wouldn’t assume that one law and we’re done. One election and we’re done. And why do we think that about an entity as big as our country when we, the owners of old houses, know that is never going to happen with an old house?

[laughter]

Tippett: Yeah. Here are some sentences from the book. “We in the developed world are like homeowners who inherited a house on a piece of land that is beautiful on the outside, but whose soil is unstable loam and rock, heaving and contracting over generations, cracks patched but the deeper ruptures waved away for decades.” And with the same metaphor you wrote, “We are [the] heirs to whatever is right or wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars or joists, but they are ours to deal with now.”

[applause]

Wilkerson: And whatever further deterioration occurs, while we did not build them or put these things in, any further deterioration is in fact on our hands. That’s when we come in. I like to view myself as the building inspector of this old house we call our country. [audience laughter] And I’ve delivered the report, “These are some of the systems that need attention.” [audience laughter] And when you get that building report, you may not want to look at it. Sometimes it could be 100 pages and you don’t want to look at it. But if you don’t look at it, it’s your own peril. It is up to us, the current occupants. While we did not erect or install the frayed wiring and the corroded pipes, they’re on us now to fix. They’re on us to repair, overhaul, whatever it takes so that it can remain standing for generations to come.

Tippett: Third metaphor: It’s like going to the doctor, and when you go to the doctor, they ask for your whole history. And it is essential to lay out your whole history if you are going to get well.

Wilkerson: Yeah. And the doctor will often not just ask your history but will ask your parents’ history, and your grandparents’ history. And sometimes the doctor will not even see you until you have already filled out that form of all the various systems in the body that might need attention because that’s how important history is. If we think of history and how we got to where we are right now in the same way we think about solving the problems, resolving or diagnosing a human ailment, then that is another way of recognizing how much more essential is it with a much larger system, an entity known as our country. And that’s one way of accessing the idea of what we have yet to do as a country.

Tippett: And this again, this image: “Looking at caste is like holding the country’s X-ray up to [the] light.” So I don’t know if talking about metaphors — [laughter] To me, this is so rich because also, something that we so underappreciate and undervalue is the power of our imaginations to change. And we also know this in a family that, in fact, what is not being named, what is not being spoken aloud, what is not being grieved or grappled with actually haunts and actually defines all of you.

Wilkerson: Absolutely. Absolutely. One purpose of all of these examples, these metaphors, these parables, all of them, is to take out the emotion that so much attaches to these discussions and to lift ourselves out of the heaviness of guilt and shame and blame and all of those things that make it personal and allow us to see that these are systems-level issues, as with a house.

And If you get that building inspector’s report, you don’t feel guilty about it. You don’t feel anything except maybe dread or maybe anxiety because you’ve got to deal with it. [laughter] But it’s not personal. It’s not personal. You just roll up your sleeves and you figure, “Okay, we’ve got to figure out what are we going to do first. What are the priorities? What’s most necessary?” That’s how you approach it. And that’s what I want people to do about our country and the challenges that we face. Not to make it personal, not to get in the weeds, but to roll up our sleeves, every single one of us recognizing that we, as the current occupants of this old house known as our country, as America, have a joint responsibility to get this right. [audience applause] Thank you.

Tippett: And I think also the fourth and final metaphor that I want to draw you out on actually really illuminates this, which is, It’s like “a long-running play.”

Wilkerson: Yes.

Tippett: And on the one hand, we are ourselves, and on the other hand, we are playing characters. We’re not the characters we play, but we are unselfconsciously in this enacting this over and over again.

Wilkerson: Yeah. I really love that metaphor, especially because it brings us back to the word “caste” and the many ways that our language adjusts to or describes that which “caste,” with an E, is speaking to. Meaning, you think about the cast, an apparatus that goes on your arm to keep broken bones in place. It’s something that is keeping you in a fixed place, or the people in a fixed place, whether they wish to be or not. When you think about the cast of a play and you’ve got a stage and someone’s stage right and stage left and the foreground and the background, and if someone steps outside of their place, then everyone on that stage, if they know the play very well, if they know the script, then they know that something has gone wrong.

And sometimes everyone will respond if there’s one person who’s stepped out of place or someone from the chorus ends up in the front, there’s a discomfort or there’s a response, there’s a recognition that something is out of place, that that’s not how it’s supposed to be. And if you’re really deeply invested in that play or in that structure, then you will know your lines, but you’ll also know everyone else’s lines. So a lot of this has to do with one’s investment in maintaining the hierarchy as it’s been, investment in maintaining the structure, investment in maintaining one’s perceived advantages, perhaps, if they are or were born to the top of the hierarchy.

Tippett: So one of the really shocking pieces of our collective story and the story of caste, that — I guess there are scholars who knew this, but I feel you really brought into the light, this terrible admiration that Hitler and the Nazis had for the United States as they prepared their reign of terror and antisemitism and extermination. Did you — was there a moment where you discovered that?

Wilkerson: Well, what put me on the path to Germany was Charlottesville, first of all, because that was in 2017. And most Americans would never put Nazi Germany — the Nazis — and the Confederates together. But those protestors, those people who were protesting the potential removal of that Robert E. Lee statue, whether other Americans recognized it or not, they were making a connection between the Nazis and the Confederacy. They had both symbols at their protest. And that’s what set me on the journey.

I was just thinking, “Why are they putting those things together? What is it about those two regimes that they felt a connection to here in this country in our time?” And that’s what set me on the journey of looking at Germany to begin with.

No, I did not know that. I wasn’t aware of it. And as I was doing the research into the connections between the United States and Germany, the first connection was the eugenics movement. They were closely, closely studying and allied with them.

[Editor’s note: The following section includes a discussion of Nazi terminology and a quotation from Hitler with an epithet that is offensive and painful. We chose to include this language to illustrate the heinous nature of the history being discussed and Hitler’s admiration for it.]

Tippett: Right. Okay, so this word, untermensch, which we think of as this key German word, this Nazi term, of dehumanization of Jews, was translated from a New England-born eugenicist who wrote about “the menace of the underman.”

Wilkerson: Yeah. And the books of American eugenicists were bestsellers in Germany and Hitler himself called one of them his bible. And this is chilling. A book written by an American eugenicist was seen as a bible for Hitler. It’s just, it’s stunning. That was my entry into this entire world of connection between our country and the Jim Crow laws, the anti-miscegenation laws in this country, the very restrictive immigration laws, which they sent people to our country to study these laws as they were beginning their work of establishing what would become the Nuremberg Laws. It was just chilling to discover.

Tippett: Some of the things I read in your book that Hitler at some point expressed how pleased he was — this is a quote — that the United States had “shot down the millions of redskins to a few hundred thousand.” That he was impressed by our communal, I think this is my word, but this communal ritual torture of lynching. And this: Hitler especially marveled at the American “knack for maintaining an air of robust innocence in the wake of mass death.”

Wilkerson: It’s chilling. And sadly, that’s part of our inheritance.

Tippett: Were there people who knew this? Has it been sitting in libraries?

Wilkerson: There are legal scholars, one particular at Yale. Professor Whitman has been a leading scholar of this. He has done the translations, he’s done tremendous work. So, yes, it’s been primarily among scholars and I think all Americans should know this. When I make mention of the human body as a way of understanding our country, it does us no good to not realize that something runs in the family. If it’s diabetes, if it’s hypertension, it does no good to pretend that it’s not there. It does no good to not know. Not knowing does not protect you from the consequences of one’s inheritance. And I view this as part of our inheritance and it is better to know than not know because it gives us a way to begin to do the work of rectifying that which we’ve inherited.

Tippett: So you lay out in the course of the book the various pillars of the caste system, and they include purity, occupational hierarchy, heritability, dehumanization, terror, and cruelty, and presumption of inherent superiority and inherent inferiority. And what strikes me is that I think those are qualities that the United States is very good at pointing out in other cultures and judging and even intervening and absolutely not associating with ourselves. And this image of Adolf Hitler looking at us is just so stunning and instructive. It’s sobering.

Wilkerson: It is. We’re so accustomed to being the city on the hill. We’re so accustomed to being the ones going in and saving others and advocating for human rights in other places. And what we have seen in recent years, there was something announced, the UN has done this various times, but they want to now study what is going on with the killings at the hands of police. Others are looking at us because we may not see it ourselves, but when we look out beyond our borders and then we see how we rank and compare to other countries, we see that we are facing a lot of challenges. One of the things I want to mention is that we’re having to come to terms with the difficult truths about ourselves, one of them having to do with COVID-19.

This is not something that gets talked about enough, I don’t think, but it’s hard to believe every time I say this, I always have to check before saying it, but our country has led the world in the number of COVID deaths. More Americans have died from COVID-19 than in any other country on the planet. How is that possible in a country with our wealth and technology that we would lead the world in the number of COVID deaths? And when it comes to COVID cases, we also lead the world. There’s something about our inheritance, there’s something about the ways that we are so distant from one another, the ways in which too many of us have felt a lack of investment in one another, that we have been programmed to see others as unworthy, undeserving, distant, and we don’t feel a connection to one another. These divisions have a real impact on how we see one another on policies, how we invest or choose not to invest in certain groups and certain people. And it’s made for a less magnanimous society.

Tippett: So I think you’re saying the harm of the pathogen spreads, it’s indiscriminate.

Wilkerson: And it hurts everybody in the end.

Tippett: It hurts everybody.

Wilkerson: Ultimately. One thing I want to say about COVID is that we could learn a lot from COVID, actually. Just think about this: this invisible organism without a brain managed to virtually shut down humanity for a time. And that is because it does not care about immigrant status or color or gender or nationality. It doesn’t care about any of those things. It will infect anyone that it has access to long enough. It recognizes what we as humans don’t think about enough and maybe don’t recognize about ourselves, and that is that we are all one species. We’re one species, and what affects one of us could potentially affect any of us. And I think we have a lot to learn from it. We should start recognizing what it knew all along and use that for the benefit of us all. [applause] I’ve actually started using the word “species” more. I think we need to remind ourselves we’re one species. [laughs]

Tippett: I have too. I’ve been using the word “species” a lot. My colleagues were teasing me about it a couple of years ago. And then I interviewed Jill Tarter, who works at SETI, the search for extraterrestrials. And she talks about earthlings. And then me talking about species felt kind of mild.

I want to just talk for a few more minutes and then we’re going to open it up for questions. We’re coming in, but if you have something you’d like to submit, maybe think about doing that in the next couple of minutes.

So even in the book, The Warmth of Other Suns, the word racism did not appear. So I’d like to talk a little bit about, for you, the importance and usefulness of this distinction of talking about caste instead of race, the clarity that it offers.

Wilkerson: Well, one of the reasons why I think caste is so useful is that it’s an ancient concept that predates what we see today. We are so focused as a country on what’s going on right now. We often don’t think about the history. That’s a long time ago. We are forward-thinking as a country. And yet what we experience now is not all that there has been. This is not the only way to divide people up. And the idea of caste focuses our attention on the infrastructure of the divisions. The broader universal structure that could be created in any society that divides and ranks people and apportions entitlements, apportions dominance, power, benefit of the doubt — a very critical thing — benefit of the doubt, all kinds of things, respect, status, honor, that sort of thing, or withholds it from certain groups.

And the idea of that kind of overarching structure that could exist in any society also allows us to see our connections to other societies that predated us or may even be concurrent with ours, to show that we think about ourselves as being exceptional. But we are members of the same species, often doing some similar things that other people in other countries of our species are doing. And this is a way of connecting ourselves with other frameworks of division in hopes that we might learn from it.

Tippett: So again, it’s about the human condition.

Wilkerson: It’s about the human condition. But one other thing I want to say about that is that in a caste system, you could use any metric, any number of metrics because it’s all arbitrary anyway. We come to recognize these things as primordial, as everlasting, as being fixed and forever, and yet race is a social construct that’s a fairly new one. Before the creation of our country and of the West, people in Europe did not identify themselves by race. They identified themselves as Bulgarian or Irish or Lithuanian, whatever they might have been, but they were not white. They didn’t need to be white.

There was a playwright in the UK that I happened to meet along the way. And she said, “You know there are no black people in Africa.” And we have to sit and think about that. Well, there’s a whole continent filled with people who are Black. And she said, “No, there are people on the land, they’re Igbo or they’re Ndebele. There are various ethnicities. There’s no need for them to be defined as Black when they look more alike than not, compared to the rest of the world.” And so, therefore, these are creations of human beings. This is the metric that was used in our country to create the hierarchy, the infrastructure that we live with. And that’s one of the ways that I think it’s really useful to connect us because there are so many parallels and intersections with other caste systems, which is what the pillars are describing. Each of those eight pillars, which are evident in India, were evident in the 12-year reign of the Nazis, also are evident here in our country.

And one other thing I would say is that — I did an afterword for this book, for the paperback, because there were so many things that had happened in the time since the book had come out. It has been out for two-and-a-half years.

Tippett: Didn’t it come out in 2021?

Wilkerson: 2020.

Tippett: 2020.

Wilkerson: 2020. Yeah.

Tippett: August 2020.

Wilkerson: August 2020, in the midst of the early months of the pandemic. And since that time — it came out actually just a few weeks, about a month, after George Floyd. And then six months later, there was January 6th. Then there was the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Then there was, just a few weeks ago, there was another horrific of so many horrific videos that we have seen of someone being killed at the hands of the police. And this was the case of Tyre Nichols. So, these were the things that had happened. These are the ways that are reminding us that because we have not dealt with these issues, then the prescriptions and the descriptions in this book continue to haunt us, because we have not dealt with these things.

And I also wanted to say one other thing about Tyre Nichols, that you asked about caste and how caste can help us to see what we otherwise might not see. And I think that case, that horrific case, is an example of how caste allows us to see something that otherwise would not make as much sense if we’re thinking in terms of race because everyone in that scene was of the same race.

Tippett: Right.

Wilkerson: But what it shows is that a caste system is a hierarchy that’s based upon policy and laws and expectations, programming that we all are susceptible to learning. In fact, it’s hard to maneuver in a hierarchical system if you haven’t learned who fits where and who is valued most, and who’s devalued.

And that was a case in which you had people who were from presumably the same group, which shows us that anyone can be susceptible to the messaging of who is valued in a society and who’s less valued in a society. And it means that those who are assigned at the very bottom of a hierarchy can be susceptible and be targeted for almost any atrocity by almost anyone, anywhere, in any group, including their own. And that a caste system requires enforcement in order to maintain what is actually, I believe, unnatural, which is to be divided up arbitrarily anyway. And that means that there can be sentinels at every rung, enforcing the hierarchy. And that’s what they were doing in that case.

[applause]

Tippett: Here’s another metaphor. One thing you’ve said is: caste is the bones and race is the skin. And this: “Race does the heavy lifting for a caste system that demands a means of human division. If we have been trained to see humans in the language of race, then caste is the underlying grammar that we encode as children, as when learning our mother tongue. Caste, like grammar, becomes an invisible guide not only to how we speak, but how to process information, the autonomic calculations that figure into a sentence without us having to think about it.”

Wilkerson: Yeah. It’s chilling to think how efficient it is at encoding and encrypting into our minds, who fits where. And that case of Tyre Nichols is where, in my view, as I look at it from someone who’s been thinking about this for years and years and years, is I see the acting out of the hierarchy autonomically, without even having to think about it. The belief that anything could be done to those who are at the very bottom with little in the way of consequences, all too often.

One thing I want to say about these videos and the impact that it’s had on us, is if you talk about reshaping, how have we all been reshaped by what we’ve emerged from in the last few years? I think the same can be said for these videos that we’re being exposed to.

If we think about it, we, as a result of the technology and the violence that is being recorded in this technology, have been exposed to things that most human beings who’ve ever lived would never see. And that is to see a human being killed before our very eyes, like George Floyd, like Tyre Nichols, like Keenan Anderson. So many people. And that means that most human beings who’ve ever lived, have not seen the things that we’ve seen unless they were on the battlefield or in an emergency room. What is the effect on human beings when they’re exposed to this level of violence? What is the effect on — of course, the effect primarily on those whose lives are being taken so brutally, but then on the rest of us, the people who have survived, to be able to see this?

Tippett: As observers and watchers.

Wilkerson: As observers and watchers. Numbing us to the pain, inuring us to the humanity of our fellow, a member of our species, because we see it so often. What does this do? What does this do to how we see one another?

But I also would say that a lot of people will mention this as a failure of policing. And that could well be, I’m not here to speak about that. But I would say when I look at this, I look to see what happens after the person is down. Now, the officers will say that they feared for their lives, and who would any of us be to question if they truly feared for their lives?

But let’s say that what happens… [audience murmurs] I agree. I agree. But what I’m saying is that not getting into the intention, let’s just talk about what ends up happening after the person is down. In these videos, time after time, after time, the person is down, no longer a threat, immobilized by whatever means the officers are using. And then what happens?

I have never seen in any of these videos, anyone present offering CPR, offering first aid, rendering even basic comfort to a member of one’s own species in their final moments on this planet. To me, that seems not just a failure of policing, it is a failure of humanity. It is a failure of our connection with one another of the same species. It requires an examination deep within our hearts, all of us, as to what our connection is with other members of our own species. That’s what I see.

[applause]

[music: “Snowcrop” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Now back to the conversation, and a bit of context for what you’re going to hear next. At this point in this live conversation with Isabel Wilkerson in the packed Benaroya Hall in Seattle, we invited audience questions. And I was brought an iPad on which those questions were supposed to appear. As you’ll hear, this did not quite work as planned, but we were able to keep moving after my producer Kayla Edwards brought me a few questions on a piece of old-fashioned paper.

Tippett: Okay. This makes me feel really old, because I remember doing events with question and answer period, where people had little three-by-five cards on their seats or their chairs. Okay. No. Okay. Let’s see if this works. I think I may need help. [laughter] We taught it my touch ID. Okay. See, it always worked though, with the three-by-five cards. It’s a WiFi problem. Okay.

[applause]

Wilkerson: Yay.

Tippett: Paper.

Wilkerson: Paper.

Tippett: All right. Well, let’s go with this one. “Are there questions that don’t get asked in spaces like this one, that you feel would help us get closer to the conversation we need to have?”

[applause]

Wilkerson: Oh, wow. I think that what comes to mind is — I get asked a lot, “What are the answers? What can we do? What should we do? You don’t give prescriptions. You don’t give answers.” And I want to start by saying that the building inspector does not tell you what to do. [audience laughs] They present to you the status of this old house that you’re in. So, that’s one thing.

Another is that those of us who are born to what has historically been the subordinated caste in our country are not the ones whose responsibility it ultimately is to fix this old house. [applause] Those of us in the subordinated group have enough to contend with when you see all that’s going on in this world.

I’m haunted by many of the cases of the police brutality against people in subordinated caste. And one of them is Jonathan Ferrell. It’s something that haunts me. And that is because he was in North Carolina and he had a horrific car accident. And he was recently finished up at Florida A&M University. He was a football hero. And although you don’t have to be a hero to be treated humanly, I’m just saying that he happened to be.

He was working at a big box store and he was apparently so beloved that his boss there said he was one of these people who would come early and do whatever you asked and just was one of those standup guys. Well, he had a horrific car accident. In fact, it was so bad that he had to climb out of the back window in order to get out. And he went to the first house that he could get to. It was at night. And he went to the first house and he knocked on a woman’s door.

And now this is at night, and I can recognize that you’re not going to just let a stranger in your house. So, that’s not what would be expected. But instead of even offering any kind of actual help, she called the police on him. Rather than calling an ambulance, she called the police on him. And the police arrived, and instead of rendering aid to a person who just had a horrific accident and had himself been injured as a result of it, they shot him to death. They shot him to death.

Now, that was because they looked at him and they used the metric that is the metric that is used in our caste system, meaning, what he looked like, sized him up, and viewed him as a threat upon sight. And did not respond to him as they should have to another member of their own species who needed help. And that’s haunting. And I feel as if those of us who are born to what has been the historic subordinated caste in our country, we have enough to contend with. So, we can’t fix all the problems in our country. And that’s why it’s a call upon all of us, everyone in our spheres of influence, to do what we can in our spheres of influence.

One of the things that I’ll often hear is that someone might be, say a nurse or they might be in banking or whatever, and they might say, “I wish we could do something about the Supreme Court.” And I’m just thinking, “You have expertise in something else. That means that you have power, influence, and expertise in the area that you’re in. And you can do tremendous help. You can have tremendous power and influence in that area.” And so, I wish that every one of us would look deeply at our lives, deeply into our hearts, assess our abilities and expertise to help fix this country. Everybody’s got a role to play. And to assess that and then figure out, “What can I do in the world that I’m in, with the power and influence that I have?”

Everyone has something. Whether it’s just if only learning ourselves what the history is and then passing it along to our children. If only learning what the history is and then passing it along to our friends. If only applying that if we’re teachers, if we’re nurses, whatever. Each system has challenges. Each system requires repair, if not total overhaul, every single one. Criminal justice, healthcare, housing, employment — every single system. So, whatever system we are part of, that’s where we can roll up our sleeves and get to work to fixing that system and not trying to fix other things that are outside of our control. [applause] Thank you.

Tippett: So, I just want to say, I don’t even know actually how to — I don’t think I’m going to be very eloquent about this, but it was very present with me as I was preparing to interview you about this, that here I am. If I take in this analysis, which makes so much sense, that I am a member of the dominant caste. And so, I’m drawing you out, and we’re drawing you out, to illuminate us. And just this image of us being in our roles. And so, I guess, this is a way to start, but it is awkward, right? To say the least. It’s painful.

Wilkerson: I want to break the roles. We need to break free of these roles. They’re constricting us, they’re holding all of us back. I think about — this is beyond just race. This is about gender. It’s about immigrant status. It’s about any hierarchy that puts one group over other groups. That is where hierarchy and caste can be applied. One of the things I say is that if we live long enough, we’ll all be part of the final caste, which would be old people. [laughter] Meaning, those who have not had to experience marginalization in the ways that other people born to the subordinated groups have experienced will experience it. Ageism is another part of this, and I include that in the book. Meaning that all of us will face the consequences of hierarchy at some point in our lives.

Tippett: Right.

Wilkerson: And I think it’s necessary then to break free of these assumptions, for all of our sakes.

Tippett: So, there are a number of questions about those who do not wish to get well. Those who deny America is sick. So, I want to know what you think about that, but I also, for me as a white person, I think there’s a really deep question on my mind about how you would like us white people to be working with each other, those of us in the dominant caste if you will. Well, there’s so much to talk about, because that’s also kind of in disarray. In disrepair. But just — what do you think?

Wilkerson: I’d like to first say a little bit about language. So, in talking about caste, caste scholars, those who’ve been studying primarily India, the language is often “lowest caste” and then “highest caste.” That’s like the traditional. So, we don’t want to do that. We don’t want to talk about high versus low, because while the reason why that’s useful is it’s positional, it’s putting it front and center that this is not personal. We are born to a place within the hierarchy, not of our own choosing, but we’re born to it. And I’m asking that we not deny that which we are born to because it has consequences for everyone, particularly those who are targeted and assigned to the bottom of it.

So, then there’s another language which would be — So, in the book, I also use the term, as you have, “dominant” versus “subordinate.” And then that becomes an issue because it suggests that one, that being dominant is the way things should be, and that being subordinate is also ever-present. And we don’t want that either. So, then it becomes “dominating” versus “subordinated,” because that’s in the same way we speak about people who were enslaved as opposed to being slaves. So, I think that language can be really powerful. The idea of making it subordinated and dominating reminds us that it is continuing. It’s an inheritance, but it continues even to this day.

What I wish that everyone could recognize is that we are all breathing the same polluted air that exists here and exists in any kind of hierarchy. And to recognize without judgment or shame or blame, that this is who we are, and this is what we’ve inherited. Let’s not deny that this is what we’ve inherited. Let’s not deny the positioning that becomes a destiny or has become destiny for far too many people.

My goal is to open our eyes to it so that we could begin to recognize what it is and then fight against it. I think we should fight with everything within us because it is hurting all of us. We live in a far more dangerous and violent country as a result of the divisions that we’ve inherited. And this puts everyone at risk.

Tippett: It’s so striking how — because again, I just think of the same idea that if it’s a pathogen, it doesn’t stay within the boxes. So, I’m very struck by you drawing the connection between this infrastructure of our country, this rigid categorization, and how that affects deaths from COVID. And it is implicated in the incredible violence that we’re also starting to normalize.

Wilkerson: Yes, absolutely.

Tippett: The way we’ve normalized race.

Wilkerson: Yeah. To me, this is part of the danger of this inheritance is that it shape-shifts. It doesn’t remain the same. And if we’re not aware of how it shifts, in the same way, we have these different mutations of COVID, we can learn so much from COVID, that it’s not going to be the same. So, what was going on in the 1950s is not what was going on in the 1970s, and it’s not what’s going on now. It shape-shifts and it shape-shifts in order to survive. That’s what it does in order to survive.

And we are the carriers of this. In the same way, we’re the carriers of COVID, we’re the carriers of caste and the programming that occurs in a caste system. We are the carriers of it. That means that we can stop it. We individually can stop it. We have control over ourselves. We certainly can stop it within our own lives. And I think that if enough people were to do it, I truly have to believe that it can be overcome. It was created by human beings, it can be dismantled by human beings.

[applause]

Tippett: There are a lot of questions about what we can do, what we can do. And I feel like you said something very profound a while ago about looking at the world that you can see and touch, the field that you can see and touch. I do still want to join that with the question of: what to do about our fellow Americans. People who are part of our world, our community, our country, who aren’t ready to be in this room having this conversation or aren’t going to read the book. I also hear you saying loud and clear, “This is not about blame.”

Wilkerson: No.

Tippett: And a lot of the way, to the extent that there’s interaction around these things in our public life, it’s very much about blame. And this is really nuanced, this move you’re making. It’s a very different move from how we have engaged this. So I’d just like to hear a little bit more, I think this is a question that’s on people’s minds. What would you like to see? As the building inspector, what would you like to see us doing in terms of self-repair?

Wilkerson: One of the things that you speak to, what does it take to convince those who are not wanting to get well or not wanting to see? I don’t know that you can make people see. I do think that you can create an atmosphere that makes for a more generous space for them to potentially hear another way of looking at the world. But I really believe that, and what I try to do in the book is to say that, to open our eyes to the ways that we are being harmed, the way that everyone’s being harmed.

So one of the things that occurred — bear with me bringing in COVID again — is that there was a study out of the Washington Post last fall that was remarking about how when COVID first hit it was disproportionately harming Black and brown people, particularly Black people and Indigenous people. They were the ones really taking the hit for this. These are people who were more likely to be exposed, having to go out and stacking shelves in a grocery store, delivering goods of people who had the luxury of sheltering in place, that sort of thing. So they were hit first.

And there was a study that came out, a report that came out in about May or June of 2020 that said that this was a group that was being harmed the most. And then what happened? It meant that those in the majority, what I would call the “dominating caste,” some said, “Well, we don’t really have to worry about it. It’s not hitting us, it’s not hurting us, so we don’t have to worry about it.” That’s human nature. I often describe myself as writing about human nature. They think I’m writing about race or whatever, but no, I write about human nature. So it’s not surprising that that would be the response. It’s sad, but it’s not surprising in a caste system. And then what happened? Well, it turns out that we’re the same species. [laughter] So because we’re the same species…

Tippett: You like making that point, don’t you?

Wilkerson: …this is what the Washington Post study showed, it turned out that after omicron, the numbers inverted. And then as of the fall, they had noted that the numbers had inverted and white Americans were dying at a higher rate than African Americans were. Why is that? Because we’re the same species. And it turned out that sense of disconnect from what was happening to other members of the species who looked different from them meant that some people were letting down their guard, felt that it wasn’t affecting them, they were somehow protected, when they weren’t because of the same species.

So this means that people are suffering and, in fact, dying because of the illusion and mythology about who is valued in the society, who matters most in the society, and who matters less. And this has real consequences. I think that if people could know the price that we pay for the divisions that we are experiencing, I would hope that that would awaken people. That’s one of the things that I sought to do. We don’t fare well, we don’t rank well with our peer nations, we simply don’t. We don’t have paid parental leave, which all of our peer nations have. One of the most…

Tippett: We don’t have what? Sorry.

Wilkerson: We don’t have paid parental leave. We don’t have parental leave.

Tippett: Oh, you’re right.

Wilkerson: Remember, we are outliers when it comes to generosity toward our own people because there are certain subsets that don’t wish to have others have something if they feel they’re undeserving of it. They’d rather forego it themselves if someone that they feel is undeserving gets something, and therefore we all suffer because of that. And I wish everyone could see that.

[applause]

Tippett: This is, again, such an important point of the shape-shifting and how this ends up hurting everyone. Something really stunning — this is not in the Caste book, but I think this is something you wrote for Time recently that you pointed out — is that the opioid crisis, which looks like a manifestation of these categories as they’ve existed shifting. And kind of the deaths, what they call “deaths of despair” of white men, but the opioid crisis you describe it has been worse for white Americans in part because of unconscious bias — that physicians believe that African Americans have a higher pain threshold and did not prescribe pain relief to the same degree for African American and Latino patients as they prescribe for white Americans, which led to this incredible catastrophe.

Wilkerson: Absolutely. That’s actually in the book. You’re right.

Tippett: Is it in the book?

Wilkerson: Yeah. It’s in the book, you’re right. That’s a way — and part of the reason for that is because, during the crack cocaine epidemic, there was a criminalization of what ultimately was a substance. It was something that was basically a medical issue, as a medical issue where you have people who are addicted to a substance, which is a medical issue, not a criminal issue. And it was criminalized when it referred to people in what I call the subordinated group, which is a group that’s scapegoated, anyway, that’s another term in the book that I use. And so that meant that the country was not prepared for when a similar kind of epidemic would arise, but affecting the dominating group, and thus they were not prepared. So that’s one way that they were not prepared. There was no infrastructure to accommodate and to respond to what would become an epidemic.

But secondly, to your point, is the cruelty of assuming that we’re a different species because people look differently and that you’re absolutely right. That there are study after study after study, studies that have been conducted that have shown that medical professionals, many of them still believe that Black people do not experience pain to the same degree as their white counterparts. And so they deny pain medication to Black patients, even those with stage four cancer have a difficult time getting pain medication. The assumption of drug addiction, substance addiction. And yet on the other hand, viewing the humanity of those in the dominating group means that there’s been an over-prescription, on the other hand, of pain medication and opioids to those in the dominating group. Thus setting in motion another epidemic that is hurting and killing people. It’s an example of how everyone suffers when those at the bottom — when the needs of those assigned at the bottom are not addressed, it is going to resurface somewhere else, like the anthrax.

Tippett: Yeah. I’m sorry I didn’t get to so many questions, and we have to draw to a close, and we started late. But there were a lot of questions that flow into these final things that I want to pick up with you. Well, there are a lot of questions about where you find hope, and I don’t want you to answer that right now. I want you to answer it at the end in a few minutes, so just…[laughter]

Wilkerson: Okay. [laughter]

Tippett: …so you get a few minutes to think about that. You said to me — when I spoke with you in 2016 you said this striking thing that is, I have quoted this so often. I have carried it with me. It’s become kind of a foundational piece of wisdom:

We changed the laws in this country, last time we really, really, really worked with race in the 1960s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, but we didn’t change ourselves. And it turns out that laws can be reversed. But you actually said to me that one of the problems, that part of our problem, part of the reason that we are so puzzled here in this young 21st century. That this isn’t solved, that in fact, it might feel as bad as it ever has, is because we changed the laws and it gave us this sense that much more had shifted.

Wilkerson: Again, it’s the assumption that something’s been vanquished, like the anthrax, when it actually hasn’t. One thing about anthrax is that it’s part of the planet and it can resurface at any time if we’re not vigilant. And I feel the same way about the toxins that live within the human heart that can resurface at times of stress, times of fraught division. And I feel that vigilance is all that we have right now until we can truly solve and get to the bottom of this.

Tippett: And again, there’s such a humanity, and, I don’t know, this language you use of “radical empathy,” which I feel is a core value for you. So even as terrible, as appalling as all of this is that we’re talking about as this inheritance is. Even for example — and this is something you said to me in 2016 — this was before the Caste book. You said, “Caste can persist in the human hunger to be better than someone else, to assure our place in society, to quell our fears and insecurities.” And those are such ever-present, understandable impulses.

Wilkerson: I am often thinking about the instructions we get on a plane about how you’re supposed to put the mask on yourself and then put the mask on those that are dependent upon you. And that means that the one thing that we have control over is ourselves. It’s the one thing we have control over and those who are dependent upon us. And I think that the era in which we are living calls upon us to get to know our country. Whenever anyone is surprised about what’s happening in our society, I’m reminded that people haven’t had a chance to know our country’s true history. Because if our country’s true history, then you know that our country’s like a patient with a preexisting condition like heart disease. And if a patient who has heart disease has a heart attack, you might be alarmed, you might be frightened, you might be hopefully moved to action. But you wouldn’t be surprised if a patient with a preexisting condition like heart disease without intervention or treatment had a heart attack.

And so I’m praying and hoping that people will recognize that unless we know our history, we can’t understand what we’re looking at. History, I often say is really what happened — it’s like walking into a movie theater — when we were going in the movie theaters more readily — when you go into a movie theater in the middle of a movie and you don’t understand what you’re looking at because you came in the middle of it and you could watch to the very end and still not know what really happened. Why is this bus that’s chasing a car that’s chasing a motorcycle, for example, you can’t understand why that’s happening. And then you’d have to scroll back and look back at what happened before you entered the theater. And that’s what history is.

And I think that it’s essential that we know how we got to where we are. I don’t think that we can get anything done unless we recognize how we got to where we are. Knowing how we got to where we are would remind us that the civil rights laws of the ‘60s didn’t solve everything. And I’m speaking about the 1860s. [audience laughter] We had civil rights laws in the 1860s, and then we had civil rights laws — and that was after Civil War — and then we had civil rights laws in the 1960s. We keep doing this over and over again because we’re not learning from our history, and we need to wake up and learn from this history.

One thing I have to mention is that we’re facing an existential crisis in our country. And that is that the 2020 Census, which was referred to — I motion toward it in the book when it came out in 2020. But the 2020 Census showed that the historic majority in this country fell for the very first time in American history, meaning the number of people who identify as white in this country fell for the first time in our country’s history. It’s still the majority by far, but it fell for the first time. No other group fell. And that we are facing in 2042 or 2045, a potential inversion of our demographics such as none of us alive could even imagine what that looks like or how that would play out.

We have 20 years to get this right. We have 20 years to establish who we are as a nation, who we embrace as a nation, what kind of country do we want to be. And that time is going to fly by. We have to get ahead of it because we’re already seeing the manifestations of fears and insecurities as a result of the potential for that inversion. And I think that it calls upon us getting on top of it and coming together to recognize what’s at stake.

[applause]

Tippett: I’m really, really holding that image… and maybe this is because of who I am and what I do, but I’m really holding that image of how whoever we are, wherever we’re, we have to create a space, where a different kind of hearing can happen. Is there something that gives you hope right now?

Wilkerson: Well, I wouldn’t have written the book if I wasn’t hopeful. Writing the book was an act of hope in itself and was an act of urgency in writing it. And our reality has only affirmed since it came out, only affirmed the urgency of understanding and seeing what’s going on underneath what we think we see when we look at our country. I do feel hopeful by people’s response to the book as it’s gone out into the world. We don’t generally, as Americans, connect our country with the concept — ancient concept — of caste. We think of India, South Asia, other parts of the world, and yet people have responded to it with a sense of really taking it deep into their hearts.

Tippett: I think it’s also that James Baldwin thing, it’s saying something that you knew was true, but somebody else had to speak it out loud.

Wilkerson: That’s so true. That really is it. And that really is it. I think we all know in our bones that something’s not right. We all know that things are harder than they have to be.

Tippett: In an interview you did with British Vogue and kudos to British Vogue for drawing this out of you, you said, “This book is a prayer. A prayer for this country, a prayer for humanity and a prayer for the planet.”

Wilkerson: It is a prayer. A lot of people will say, “She argues this and she argues that.” I do not argue. You know I don’t argue. [laughter] This book was a prayer for our country. It was a prayer for humanity. It was a prayer for our species. It was a prayer for the planet because this has consequences for our planet as a whole.

Tippett: I thought that I asked you before if you want me to read this or if you want to read it, but I’d like to just read the last few paragraphs of the book. And before I do that, I want to just thank you for not making your argument, [laughs] but caring about the human heart and helping us learn things that we needed you to come along and name for us to know were always true.

And where is it?

In a world without caste… Oh, and the title of the epilogue is “A World Without Caste.”

“In a world without caste, instead of a false swagger over our own tribe or family or ascribed community, we would look upon all of humanity with wonderment: the lithe beauty of an Ethiopian runner, the bravery of a Swedish girl determined to save the planet, the physics-defying aerobatics of an African-American Olympian, the brilliance of a composer of Puerto Rican descent who can rap the history of the founding of America at 144 words a minute—all of these feats should fill us with astonishment at what the species is capable of and gratitude to be alive for this.

In a world without caste, being male or female, light or dark, immigrant or native-born, would have no bearing on what anyone was perceived as being capable of. In a world without caste, we would all be invested in the well-being of others in our species if only for our own survival, and recognize that we are in need of one another more than we have been led to believe. We would join forces with indigenous people around the world raising the alarm as fires rage and glaciers melt. We would see that, when others suffer, the collective human body is set back from the progression of our species.

A world without caste would set everyone free.”

[applause]

Tippett: Thank you. Thank you all for coming.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: Isabel Wilkerson’s book is, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. She’s also the author of The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. She previously won the Pulitzer Prize while reporting for The New York Times, and was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama.

Special thanks this week to Alison Stagner and Rebecca Hoogs at Seattle Arts & Lectures. And also at Benaroya Hall: James Frounfelter, Jon Roberson, Aaron Gorseth, Ira Seigel, and Dave Kobernuss.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Amy Chatelaine, Romy Nehme, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Juliana Lewis, and Tiffany Champion.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America — one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The George Family Foundation, in support of On Being’s civil conversations and social healing work.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.