Sue Phillips

Amadeus

What does it mean to be good? What does it mean if we aren’t good? Whose fault is it? These are just some of the questions that animate Amadeus, a fictional portrayal of famed composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his musical rival Antionio Salieri. These questions also inspire Sue Phillips, a Unitarian Universalist minister. She first watched the movie in the late ’80s, just as she was coming out and understanding her place in the world.

Image by Julia Kuo, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Sue Phillips is the co-founder of Sacred Design Lab. She was also the first Director of Strategy as part of the Impact Lab here at the On Being Project. An ordained Unitarian Universalist minister, Sue is the co-author, with colleagues Angie Thurston and Casper ter Kuile, of Design for the Human Soul.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with the Reverend Sue Phillips about the movie that changed her life — Amadeus. Don’t worry if you haven’t seen it. We’re gonna give you all the details you need to follow along.

[music: “Symphony No. 25 in G Minor, K. 183, 1st Movement” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

When I think about the movie Amadeus, the first thing I think about is his laughter, the laughter of the actor Tom Hulce as he portrays Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in the 1984 movie. It’s a movie that, when I was a kid and watched it I didn’t really understand fully. Classical music was a world that my father was into, my brother was into and I didn’t really feel a part of it. It always felt really foreign and adult and quite honestly boring to me, even though I was taking piano classes at the time because my father really encouraged it. I never connected with it, and watching the movie with my dad felt like I was being led into this secret world for the first time.

[Excerpt: Amadeus]

[music: “Marriage of Figaro, Act IV, Ah Tutti Content” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

It’s important to remember that Amadeus is a fictional account of Mozart’s life, and here he’s portrayed as a kind of playboy: eccentric, over the top, a dramatic kind of queen in a lot of ways. He takes command of every room he’s in. He’s incredibly young and he’s also a genius. And this a thing that you get a sense of throughout the whole movie is the genius that Mozart carries within his fingertips and in his brain and just in the way he thinks about music. And that it comes to him without any effort, it seems.

[Excerpt: Amadeus]

Mozart’s rival is Salieri, played by F. Murray Abraham. Salieri is an established composer and a man of deep faith, but he doesn’t have the raw talent Mozart has — and he knows it. And this makes Salieri incredibly jealous, scheming, petty — but more importantly, he feels betrayed by God. How could God bless someone like Mozart with that kind of talent?

[music: “Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201, 1st Movement” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

[Excerpt: Amadeus]

The kinds of theological and moral questions illustrated through Amadeus and Salieri’s rivalry resonated with Sue Phillips. As a Unitarian Universalist minister, she’s someone who has wrestled with inner questions around who God is and what he wants from us — and Amadeus reflected these questions back to her.

[“Mass in C Minor, K. 427, Kyrie” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

Ms. Percy: I’m gonna take you to a contemplative place, so prepare yourself.

Sue Phillips: Always ready, my sister.

Ms. Percy: I want you to go back to the first time you saw Amadeus and just think about how old you were, where you were, what was going on in your life at the time. And I’m gonna let you sit here in silence for ten seconds, and then I’ll chime back in.

Rev. Phillips: Great.

Ms. Percy: So what memories came up for you?

Rev. Phillips: Well, thinking back to when I first watched it, it was in the late ’80s. These were the Reagan years. I was a young college student. And I was so curious about who I was in the world and what was my place in it. And also, as a queer kid who was just really coming out, this movie gave shape to the questions that were in me that I didn’t know how to give voice to — questions about the nature of meaning, of what it means to be human, of why bad things happen in the world; all these rich — now I know to name them theological questions, but couldn’t have at the time. And there’s a way in which Salieri’s such specific engagement with God gave me God-shape, if you will, to those questions.

But also, if you think about the cultural narrative of the ’80s, being a gay kid — a word, incidentally, which I did not think had anything to do with me, strangely enough, because this was the days of the Moral Majority and just grotesque public words about what homosexuality is and was. So I knew there was something fishy about the way people talked about God, because the context in which I heard reflections on what was supposedly my life were so obviously not right, it actually raised — it gave me the permission to ask questions about who God is, because I knew that whatever people were saying about God could not possibly be true. So I was very curious on that level.

[Excerpt: Amadeus]

Ms. Percy: So when I first saw Amadeus — I was trying to remember, I was probably either 10 or 11. And my father, who plays classical guitar, it was important for him that my brother and I learn an instrument. And so I had been in piano for many years at this point — I think at least five years, four or five years — and I was not good. I was not a great piano player. I was still playing the same beginners’ songs. But I didn’t know that I wasn’t good until I saw Amadeus, and I was like, “Oh, I suck. I’m not just not-good; I’m really bad.”

Rev. Phillips: Oh, honey. Oh, it’s so hard.

Ms. Percy: But what’s fascinating, in re-watching this movie now, at the age of 36, and having not seen it since that time is what a different experience I had, watching it. When I watched it with my dad, and he’d seen it before, and he was making fun of the character, Salieri. Any time Salieri would be really hurt or just indignant over Mozart’s genius, he really felt himself — he just laughed at him continuously.

Rev. Phillips: Oh, dear.

Ms. Percy: All my memories of the movie are of my father laughing at this character, and it really shaped the way that I viewed Salieri. And watching it now, I was crying at certain points, watching this man and his frustration and heartache over not having the ability to not just be a genius, but almost, speak for God, because that’s the thing that comes through so beautifully in the movie. There’s always the repetition of, he feels that God chose Mozart, and God, then, didn’t choose him, as a result. There’s that direct comparison. There are these lines that he says — “All I ever wanted was to sing to God. He gave me that longing and then made me mute. Why? If he didn’t want me to praise him with music, why implant the desire like a lust in my body and then deny me the talent?”

Rev. Phillips: There it is. This is an essential human question. And that’s why I love this movie so much, is, if you — so many of the questions at the heart of this movie are the questions that most of us have: What does it mean to be good? What is it like to believe in a God if we believe that God has a hand in human history, and therefore, creates our successes and is the author of our failures? What does this mean when we experience what every human experiences — namely, failures and successes?

This is really a devastating theology at the heart of Amadeus. And of course, by “theology” I just mean, how do we think about ultimate meaning and value, and the purpose behind it? And in this case, obviously, Salieri has a very grim notion of who God is, even though there’s also a devotional heart to it that is so compelling. So, by the time we see him — actually, at the start of the film, almost the opening scene after the title sequence, remember that Amadeus takes place entirely as a flashback, in the context of a pastoral encounter between a priest and Salieri in an insane asylum.

Ms. Percy: Exactly.

Rev. Phillips: And at the very start, the priest sits down; Salieri says, “Do you know who I am?” And the priest says, “It doesn’t matter. All men are equal in God’s eyes.” And Salieri sits up and says, “Are they?” Because his experience is that, in fact, all men are not equal in the eyes of God.

Ms. Percy: Not equal, yeah.

Rev. Phillips: Now, I can totally identify with that. Why are some people successful and others not? Why are some folks given obstacles, and others, not? Am I responsible for the hardship in my life? These are questions that — I don’t know about you, but these live in my life, and certainly, especially, lived in my life at this earlier age of reconciling who I thought I was.

[Excerpt: Amadeus]

And I think Salieri is a deeply compelling and compassionate character.

Ms. Percy: He’s not the villain, which is the way that I saw him as a child.

Rev. Phillips: No, not at all. Not at all.

[Excerpt: Amadeus]

Ms. Percy: So how did these questions that arose in you from watching this movie — how did they continue to shape your life as you were re-watching it over and over again? You were in your 20s when you first saw it, and it’s been decades since — not to age you. [laughs]

Rev. Phillips: [laughs] Go ahead.

Ms. Percy: She’s 95. No. But yeah, I’m just so curious as to how these questions kept popping up in your life, and what you learned from the Salieri character.

Rev. Phillips: Well, first of all, that people are complex, and that a love and desire to be good can animate even the worst behaviors. And I do think there’s something about this movie that has implanted in me a compassion and, perhaps, the gift of being able to see complexity. I think all human hearts can see complexity, but this movie is very morally complex, I think. And I’ve — in a way, I’ve devoted my life to staying in those kinds of questions. Which of Salieri’s questions, when you think about the whole range of questions that he was just raging about, which of those questions really lived, and live, for you?

Ms. Percy: As someone who — one of the worst parts of me is comparing myself to other people.

Rev. Phillips: Oh, dear.

Ms. Percy: So I really relate to him on that front, the idea of being a patron saint of mediocrity. That really spoke to me, and the idea that God could still use you if you are mediocre.

Rev. Phillips: Preach, sister.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Right?

Rev. Phillips: Really. How did you come to know that?

Ms. Percy: I don’t think I know it, still.

Rev. Phillips: Still learning. Me too. Me too, for real.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Still learning, because I still make the mistake of comparison, of still looking at someone and saying, “Well —” that they’re clearly being used by God; that that is what I should be doing, and then looking at myself with that harsh, critical lens. And I think that’s the really beautiful thing that Salieri embodies, is showing us what can happen: We can end up in a madhouse, completely devoid of faith and love in God and from God, because we’re so intent on looking at what we aren’t, instead of what we are.

Rev. Phillips: I’m way too much of a Unitarian Universalist to believe that suffering is inherently redemptive, of course, because we cause so much for each other. But Salieri earned his experience, and so do we all.

[excerpt: Amadeus]

Ms. Percy: Each week in the This Movie Changed Me newsletter, we ask you to reflect along with us about how movies have changed your life.

We loved what Nikki Hunt shared with us:

“In 1997, I saw the movie All Over Me, and the painful, dramatic love relationship between the teenage girls validated my experience with my best friend in high school. Not only was my experience validated, but I also had an epiphany — that I could like men and women, and I did not have to choose. Until I saw this movie I had not realized that I had submerged and caged a whole section of myself. My whole life opened up in so many wonderful and amazing ways after seeing this movie”

Thank you Nikki for sharing your story with us. And we’d love to keep hearing from all of you, so send us your reflections at onbeing.org/tmcmletter.

[music: “Piano Concerto in E-Flat, K. 482, 3rd Movement” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

Ms. Percy: What do you think it means that the last scenes of that movie are him walking down the corridor in this madhouse? If I remember correctly, he’s going around, saying, “I absolve you. I absolve you,” as he’s walking down that corridor. And then we hear Mozart’s laugh, for one last time. What does that — how do you interpret that in the arc of his journey?

Rev. Phillips: What an interesting question. I had always — I’ve always experienced that scene as a bit of a toss-off; that in the end, Salieri has simply given into his — into the lust he talks about, earlier in the movie — the lust of his revenge, and his depravity, basically. I see that as a submission to one way of understanding his story, because remember, earlier in the movie when he speaks to the priest, Salieri expresses concern that people think he killed Mozart, even though the movie actually opens with a confession. So I think he’s unsure, even in himself, the extent to which he caused Mozart’s demise, and I just see the end as a sort of capitulation to the inner story that he caused it, that he’s just embracing this depraved idea of himself — which, let’s face it, is an option for all of us. The fact that it has grandiose elements — “I’m the patron saint; I absolve you” — does not rescue it from this deep sadness at the heart of what must be that experience for this character.

Ms. Percy: See, I took it as being him voicing what he hoped God would say to him.

Rev. Phillips: Ooh. Do you think?

Ms. Percy: Yeah, I think so, because I think, especially in that conversation, like you pointed out, we experience the movie through flashbacks from his point of view as he’s telling the story to the priest. And I feel like, toward the end, he’s come to see — and the priest doesn’t say very much. But the few things that he does say, I think, leave enough of an impact on him, where he can maybe look at him in a kinder light, maybe even the way that God looks at him, this new kind of newfound God. And so I think about him walking through that corridor and saying this to all these people who have been cast out by society. And he’s going around, saying, “I absolve you,” to all of them. And I think he’s speaking to himself.

Rev. Phillips: Liliana, I think you might be a Universalist. This is a very optimistic interpretation.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] This is where I convert.

Rev. Phillips: Right here, my toaster, at last. [laughs]

Ms. Percy: [laughs] That’s hilarious.

Rev. Phillips: I like it, though. I would love to think that was true.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] It’s a little too positive?

Rev. Phillips: Well, I don’t know, girl. You keep your interpretation.

Ms. Percy: That’s the great thing about movies. [laughs]

Rev. Phillips: Movies, here we are.

[music: movie soundtrack]

[excerpt: Amadeus]

Ms. Percy: So when you watch this movie now, like you did last week, and you think about where you’ve come on your own journey, what do you continue to learn about it? What are the lessons that you took away last week, versus what you took away that first time?

Rev. Phillips: All the same questions that animated my young adulthood still live.

Ms. Percy: They’re still with you?

Rev. Phillips: I just have different versions, and I am so grateful for work that keeps me in the questions. And I’ve realized, it’s gonna perhaps even sound a little cheesy, but it’s that giving shape to questions that evoke the longing and experience that everybody — most people share is more powerful, in many instances, than being able to answer them, partly because the answers are much more provisional than the questions, and so, to have the guideposts of a great question — that’s something that can be a narrative through-line of a life, of a human life. And it certainly has been mine, from the questions in this movie. So there you have it. Something about my inner life is so represented in this movie.

Also, as a “One” on the Enneagram — for folks who don’t know, this basically means that a core motivation of mine is to be “good,” and I’m always scanning for, “Am I being good?” And these questions are so about: What does it mean to be good? What does it mean if we aren’t good? Whose fault is it? Does God care, if God rewards “obscene little creatures,” as Salieri calls Mozart in this movie? What does that mean? So I just return to these questions, over and over again.

Ms. Percy: One of my favorite books is this book by John Irving, called A Prayer for Owen Meany. I don’t know if you know it.

Rev. Phillips: I read it so many years ago. Tell me about it.

Ms. Percy: Well, he has a thing that blew my mind at the time — I read it as a high school student — that I’d never thought about, which is the idea of everyone having a role. So there’s no Jesus without a Mary and a Joseph; and that Joseph, especially, seems like kind of a useless character — he’s a throwaway, he’s just the guy who’s there — but that in the story of someone’s life, there has to be that throwaway character, or that seemingly throwaway character who, actually, is hugely important. And in watching this movie, I kept thinking about that with Salieri — that he, himself, diminishes his role, even in Mozart’s life. And Mozart continues to go back to him. He mocks him a little bit and sees him as beneath him, musically, but he does keep going back to him, and he plays such an important role in his life. And I just wonder how that dynamic maybe influenced your view of what each one of us can bring, in the world.

Rev. Phillips: I have to confess that in most cases, when I have encountered situations that are reminiscent of this in my own life, I don’t realize the value of characters like Salieri is in Mozart’s until well after the fact …

Ms. Percy: You are human, my friend. [laughs]

Rev. Phillips: … when grace has perhaps intervened, and you can extract more of the lessons.

Ms. Percy: In hindsight, yeah.

Rev. Phillips: Yeah, but I mean — Mozart, in the story, relies on Salieri in the way that we do, when — we learn a lot about who we are by pushing and pulling against somebody we think we’re not, and especially as younger folks, when we don’t have a lot of clues about our own identity, much less who we want to be. And you can see this playing out between these two men. And then, the intimacy of the one of the final scenes, where Salieri is actually taking dictation for the Requiem …

Ms. Percy: As Mozart is dying.

Rev. Phillips: … as Mozart is dying. And there’s a beautiful — “intimacy” is the best word I can think of. So there’s also that. There is a real intimacy in that kind of dynamic, even though it’s not, theoretically, a friendly one.

[excerpt: Amadeus]

How desperate each man is to be connected to music. This is what they have.

[music: movie soundtrack]

[excerpt: Amadeus]

Ms. Percy: And that also, sometimes, people are given gifts that they don’t deserve; and that’s OK, and that’s life. Like Mozart, arguably, was not a great person — or, at least, that’s how he’s portrayed in this movie. I know nothing about the real person. I get all of my knowledge from movies. [laughs]

Rev. Phillips: What do you think it means, to “deserve,” though? Who —

Ms. Percy: Well, that’s the question that I know you’re asking. [laughs]

Rev. Phillips: Now I’m gonna turn the tables on you. Am I allowed to do that with the host?

Ms. Percy: Yes, you are. [laughs]

Rev. Phillips: It’s curious.

Ms. Percy: It’s a great question. By whose barometer am I judging him? I’ll tell you why I feel like he doesn’t deserve it. It’s because he — it seems easy.

Rev. Phillips: It’s too easy.

Ms. Percy: It’s too easy for him.

Rev. Phillips: Is it? I just don’t experience somebody whose life is like Mozart’s is depicted in this film as having an easy life. He was unwell. He was presumably addicted to booze and to the distraction of — it might be torturous to receive dictation from God.

Ms. Percy: That’s a great point. It drives you mad.

Rev. Phillips: There is such a historical correlation between so-called insanity and receiving special messages, if you will, from many people’s gods. This is a whole archetype in religious history. So I don’t see Amadeus as having — Mozart, excuse me — which, by the way, the word, “Amadeus,” means — it’s an imperative that means, “Love God.”

[music: “Requiem, K. 626. Lacrymosa” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

Ms. Percy: Oh, I didn’t know that.

Rev. Phillips: Yes, “Love God.”

Ms. Percy: So that they named him — wow.

Rev. Phillips: Yes. Just to piss Salieri off even more, he has to say that, over and over again.

Ms. Percy: “Amadeus. Amadeus. Amadeus.” [laughs] I didn’t think about the fact that it could be a by-product, the way that his life proceeded, because of his connection to God. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

Rev. Phillips: Depends on where you think the gifts come, along with the suffering. I don’t know; do gifts come from God? I’m not sure.

Ms. Percy: You’re just asking me all these questions. I have no answers for you.

Rev. Phillips: Well, I don’t either. That’s why I’m asking you, Liliana Maria. I had hoped. I had hoped. But let’s just stay in the questions together.

[music: “Symphony No. 25 in G Minor, K. 183, 1st Movement” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]

Ms. Percy: Sue Phillips is the co-founder of Sacred Design Lab. She is an ordained Unitarian Universalist minister, and was also the first Director of Strategy as part of the Impact Lab here at the On Being Project. Sue is the co-author, with colleagues Angie Thurston and Casper ter Kuile, of Design for the Human Soul.

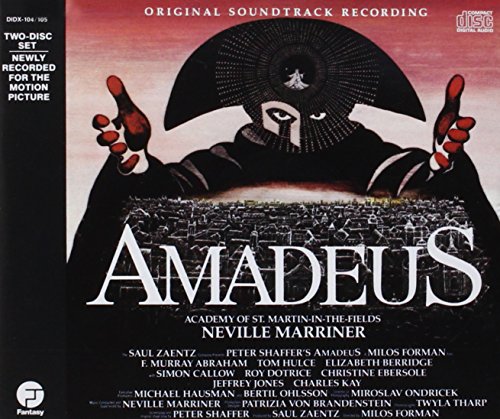

Amadeus was produced by The Saul Zaentz Company and is now owned by Warner Brothers — the clips you heard in this episode are credited entirely to them. The music we featured from the movie can be found on the “Amadeus: Original Soundtrack Recording” from The Saul Zaentz Company, but is also pretty much all Mozart, so we should just credit him.

Next time on This Movie Changed Me, I’ll be talking with my living movie prophet Mark Kermode about the horror classic The Exorcist. You can find that streaming in all the usual places, and I promise you’ll survive if you watch it.

The team behind This Movie Changed Me is: Maia Tarrell, Chris Heagle, Tony Liu, Kristin Lin, and Lilian Vo. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. And we also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett and Becoming Wise — find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

I’m Lily Percy, and I’m going to do my best to be kind to my inner Salieri — please do the same.