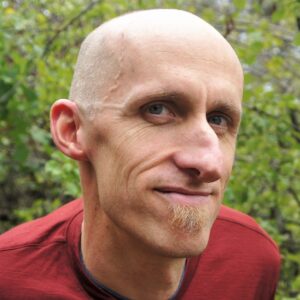

Andy Jackson

The change room

When all eyes seem to lock on you, how do you cope with self-consciousness? How do you look back?

We’re pleased to offer Andy Jackson’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Andy Jackson is a poet preoccupied with difference and embodiment. His first published book of poems, Among the Regulars, was shortlisted for the 2011 Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry. Andy’s most recent poetry collection is Human Looking (Giramondo, 2021), shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Prize for Poetry. As he notes on his website, "these autobiographical and biographical poems speak with the voices of the disabled and disfigured, in myth, art, history and the present moment."

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama. And a few years ago, I was in a car with a friend of mine; he was driving, and his sons, who were both under 10, were in the back of the car. And one of the sons shouted, Look at that man!, pointing to a guy using crutches on a footpath. And my friend pulled the car over and said to the boys, We need to talk. And they were curious about the guy using crutches. My friend was saying, How do you talk about bodies? And why did you want to do that? And how do you think he’d feel?

I realized, in the way that he unfolded that with the boys, that curiosity isn’t necessarily neutral. And it was such an interesting lesson for them, and for me, observing this unit of family, this unit of learning, and this unit of turning the question of curiosity back on the questioner. I’ve thought about that so often, in my relationship with the need to know. When I look at a life, when I look at my own, do I need to know?

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The Change Room” by Andy Jackson:

“This morning, walking almost naked

from the change room toward the outdoor heated pool,

I become that man again, unsettling

“shape to be explained.

Such questions aren’t asked to my face. Children

don’t mean anything by it, supposedly, so I

“shouldn’t feel as I do,

as my bones crouch into an old shame I thought

I’d left behind. Chlorine prickling

“my nostrils, a stranger

compliments me on my tattoos and shows me hers –

a dove in flight over a green peace sign –

“as if the canvas was unremarkable.

She turns and limps away,

and something makes a moment of sense.

“I lower myself into our element

and swim, naturally

asymmetrical and buoyant. Quite some time

“later, showering, the man beside me

is keen to chat – how many laps we’ve each done,

how long I’ve lived in this town, the deep

“need for movement.

Speaking, our bodies become solid.”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

This poem, “Change Room,” by Andy Jackson, is about so many things, bodies being one of them. And body language is present in the poem; it opens with “This morning, walking almost naked / from the change room.” So we hear “naked” and then “my face,” “my bones,” “my nostrils,” “my tattoos.” It’s a poem that pays attention to an experience of one person and their body, but really that’s a sleight of hand, because Andy Jackson is looking at the attention that he gets in his body and is refocusing it, extending it wider, looking at the deeper question of, what does it mean for any of us to be in a body, and how do we in bodies relate to others in bodies?

This poem is from a book called Human Looking that Andy released recently. And he’s a hugely celebrated Australian poet, and he has a genetic condition called Marfan Syndrome, which for him includes severe spinal curvature. The tagline on his website is “Poetry from a body shaped like a question mark.” And he, in the earlier parts of this poem, is focusing attention on the experience of having attention focused on him all the time. He’s walking toward the pool, and

“I become that man again, unsettling

“shape to be explained.

Such questions aren’t asked to my face. Children

don’t mean anything by it, supposedly, so I

“shouldn’t feel as I do” …

And this experience is one of shame — “my bones crouch into an old shame I thought / I’d left behind.” There’s a question of years here. There’s a question of still, as an adult, capable of feeling shamed by the questions you know that children are asking. And I love the bravery of challenging the narrative that’s put on children and challenging what children say, in this. Do we listen to ourselves — “Children / don’t mean anything by it” — or do we listen to somebody like Andy Jackson in the poem, and his powerful “supposedly”?

[music: “Catching Water” by Gautam Srikishan]

There’s a turn in this poem, which is so subtle. Often, a turn in a poem is happening where something is being looked at through a different lens — something new emerges, something deeper. Something is happening on the surface, and the poet wants to say, Let me go under the surface, and deeper, and deeper still. The turn happens with “Chlorine prickling / my nostrils, a stranger / compliments me on my tattoos.” Something is about to be irritated. Something is asking for attention.

And a stranger comes and compliments him on the tattoos and then shows hers, and this is the beginning of an experience of bodies speaking to bodies. And when she “limps away,” he says, “something makes a moment of sense,” because he’s saying he doesn’t know why it is that she came up to talk to him about his tattoos and share hers. They made this connection. She clearly wasn’t somebody that was going to be hurling her own projections on his body. But he doesn’t know why. Something only made “a moment of sense.”

Then he goes into the water: “I lower myself into our element / and swim, naturally / asymmetrical and buoyant.” This is a place within which a body experiences itself differently.

And then the turn continues — it’s almost like there’s three stations of the turn. There’s the turn to the woman with the tattoos, there’s the turn into the element in the water, and then a different experience of water, “[q]uite some time // later,” in the showers, with someone who’s keen to talk. And they have this conversation, which is person-to-person, in an exposed way speaking about things that matter. The topics of their conversation, too, go from the everyday — laps — to where do you live and how long you’ve lived, which is part of your story, and then into something almost anthropologically significant, “the deep / need for movement.” This is a conversation that too has gone from depth to depth to depth. And it is person-to-person in their own unique bodies, different, but without the grotesque nature of comment and that deep attack of comparison.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Speaking, our bodies become solid” — this poem is a mystery and an open experience at the end, a question, to say, what does that mean? What does it mean to feel like your body is solid, rather than your body is something else? And is that something we can do for each other? This, I think, is an invitation in this poem, to feel what “[s]peaking, our bodies become solid” might mean, rather than to find an easy explanation for how this line works in the poem. Perhaps this is why it’s only a two-line stanza at the end — that it’s inviting a response. It’s inviting whoever is reading it to continue the conversation, body to body.

And the invitation in the poem is an invitation into a kind of human encounter, as you experience it in the three turns — his own experience in the water, the conversation with the woman with the tattoos, who compliments his, and the conversation with the man in the shower. Difference is never eradicated in this poem, but embodiedness is amplified in this poem, where people have the capacity to speak to each other.

“The Change Room” is the title, and the question is, who is it that needs to be changed, and what is the change that needs to happen in this room? This is the wider question of this poem, not about anybody’s experience of their body, or not about anybody’s demand that someone should explain their body. Really the question is, what is the change that needs to happen in the conversation about bodies? Especially, I think, this poem is amplifying the people for whom they think their body doesn’t need to be explained, that they’re being invited into a change room of a new conversation.

[music: “Orchard Lime” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“The Change Room” by Andy Jackson:

“This morning, walking almost naked

from the change room toward the outdoor heated pool,

I become that man again, unsettling

“shape to be explained.

Such questions aren’t asked to my face. Children

don’t mean anything by it, supposedly, so I

“shouldn’t feel as I do,

as my bones crouch into an old shame I thought

I’d left behind. Chlorine prickling

“my nostrils, a stranger

compliments me on my tattoos and shows me hers –

a dove in flight over a green peace sign –

“as if the canvas was unremarkable.

She turns and limps away,

and something makes a moment of sense.

“I lower myself into our element

and swim, naturally

asymmetrical and buoyant. Quite some time

“later, showering, the man beside me

is keen to chat – how many laps we’ve each done,

how long I’ve lived in this town, the deep

“need for movement.

Speaking, our bodies become solid.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “The Change Room” comes from Andy Jackson’s book Human Looking. Thank you to Giramondo Publishing, who gave us permission to use Andy’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Kayla Edwards, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.