Annette Gordon-Reed and Titus Kaphar

Are We Actually Citizens Here?

We must shine a light on the past to live more abundantly now. Historian Annette Gordon-Reed and painter Titus Kaphar lead us in an exploration of that as a public adventure in this conversation at the Citizen University annual conference. Gordon-Reed is the historian who introduced the world to Sally Hemings and the children she had with President Thomas Jefferson, and so realigned a primary chapter of the American story with the deeper, more complicated truth. Kaphar collapses historical timelines on canvas and created iconic images after the protests in Ferguson. Both are reckoning with history in order to repair the present.

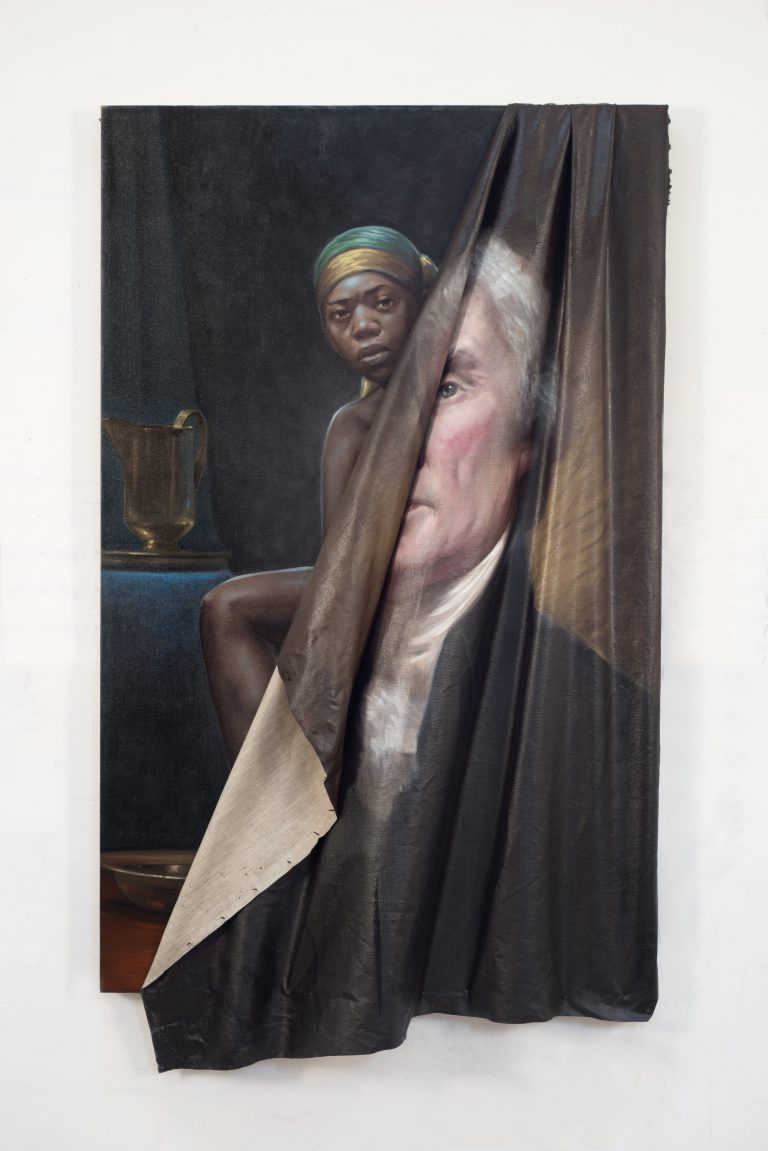

Image by Titus Kaphar/Jack Shainman Gallery, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Titus Kaphar is an artist whose work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions from the Savannah College of Art and Design and the Seattle Art Museum to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His 2014 painting of Ferguson protesters was commissioned by Time magazine. He has received numerous awards including the Artist as Activist Fellowship from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and the 2018 Rappaport Prize.

Annette Gordon-Reed is the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History at Harvard Law School and a professor of history in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. Her books include The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize, and “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: In life, in families, we shine a light on the past to live more abundantly now. Today’s show is a conversational exploration of that as a public adventure. Annette Gordon-Reed is the historian who introduced the world to Sally Hemings and the children she had with Thomas Jefferson and so realigned a primary chapter of the American story with the deeper, more complicated truth.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Annette Gordon-Reed: He was a multifaceted — as we all are, incredibly complicated — but somebody who existed at the forefront of his society. Studying him is a study of America in many, many ways, because so many of the paradoxes, so many of the dilemmas that exist in his life are in the country.

Ms. Tippett: Painter Titus Kaphar created iconic images after Ferguson. He collapses timelines on canvas.

Titus Kaphar: It became very clear to me that if I wanted to know that history, I was going to have to seek it out on my own. I had to sort of manipulate what I had and work with what I had to create a narrative that I didn’t see or hear.

Ms. Tippett: Is that when you started painting?

Mr. Kaphar: I think people would say that’s when the work got political. I say that’s when the work got personal.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being at the 2017 Citizen University National Conference in Seattle.

Ms. Tippett: I love the title for this gathering: “Reckoning and Repair.” And right now there are questions that we are all asking. How did we get here? What just happened? And most importantly, how shall we live? How do we live forward? How do we live forward together? This is reckoning we’ve put off and put off and put off. And in this room of civic reflection and social courage, I want to pull back the lens to the last 20 months and the last 20 years and the last 20 decades. And I can’t imagine a better, a more exquisite pair of conversation partners to do that than Annette Gordon-Reed, a citizen historian, and Titus Kaphar, who is a citizen artist.

I just want to begin with starting with hearing a little bit from each of you about the roots in your life, in your formation, of your ability to see and hold complexity and history in yourself and to hold it before the rest of us.

Annette, you grew up in East Texas. You’ve said that very early in your life, as a young girl, you became fascinated with history and in particular with the paradox of this figure of Jefferson. And I wonder what in the background of your childhood encouraged that curiosity and that clarity in you.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Well, I, as you said, grew up in East Texas. And I integrated the school district. I was the first black child to go to “the white school” in our school district. And I was in first grade, and I was introduced to the idea that politics mattered, that race was a thing, and that we had a history — that this came from someplace. And, just from — being in this situation where I had to crack a code, crack a social convention gave me a sort of insight, made me start to think about how we got here.

Ms. Tippett: And it’s interesting — in the way you talk about discovering Jefferson, for example, even then, and later on, even after you had written the book about him and Sally Hemings and that whole story — that you continued to find him, what did you say, “a magnificent and horrifying figure,” all at the same time.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Well, yes. He was a multifaceted — as we all are, incredibly complicated — but somebody who existed at the forefront of his society. Studying him is a study of America in many, many ways, because so many of the paradoxes, so many of the dilemmas that exist in his life are in the country. So he’s interesting, but his connection, the way he personifies so much of the conflict that we have is even more interesting.

Ms. Tippett: And Titus, you collapse timelines on canvas. I want to just read some words of yours about your work. “I paint and I sculpt, often borrowing from the historical canon, and then alter the work in some way. I cut, crumple, shroud, shred, stitch, tar, twist, bind, erase, break, tear, and turn the paintings and sculptures I create, reconfiguring them into works that nod to hidden narratives and begin to reveal unspoken truths about the nature of history.”

You grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and I wonder, how do you trace — what planted this fearlessness and creativity with which you attend to history on behalf of all the rest of us?

Mr. Kaphar: Well, I started painting really late. I had already sort of constructed my ideas about the world. I was about 27 when I made my first painting.

Ms. Tippett: Really?

Mr. Kaphar: I was taking an art history class. And in this art history class — it was one of those survey classes where you try to teach way too much in a semester, so you start with cave paintings and end with de Kooning.

[laughter]

So in that class, when I looked at the textbook at the beginning of the semester, I looked in the book, and there were about 14 or so pages on black people and painting. Now it didn’t seem like much. It wasn’t much in a book that was like 400 pages. It seemed strange to me. But I remember thinking, “At least it’s here.” Now, it included every time a black person was represented in a painting that they thought was significant.

Ms. Tippett: So it wasn’t even just black painters. It was black …

Mr. Kaphar: No.

Ms. Tippett: Wow.

Mr. Kaphar: No, it was just in general. And so I sat through that class, and I did well in the class and really enjoyed the professor in that class. But when we got to that section, the day of class when we got to that section, the professor went to the front of the classroom and said that “we don’t have time to go through this section, so we’re going to skip over it.” I was the only African American in the class, and I raised my hand, and I said, “I’ve been really looking forward to this. And clearly the author thought it was significant, so maybe we could figure something out.” And she said, “Titus, I don’t have time for this. We’re not going to go through this.” And it became very clear to me that if I wanted to know that history, I was going to have to seek it out on my own. I had to sort of manipulate what I had and work with what I had to create a narrative that I didn’t see or hear.

Ms. Tippett: Is that when you started painting?

Mr. Kaphar: I think people would say that’s when the work got political. I say that’s when the work got personal.

Ms. Tippett: Annette, you wrote this really interesting and hopeful but also reality-based article [laughs] in 2008, after the election of Barack Obama. One of the things you pointed out was that for you the Obama candidacy, as you said, was a bet that the conventional wisdom about what we knew of white Americans was faulty or incomplete and that you also had that experience when you wrote this book with this revelation about our founding father — that you expected there to be huge resistance to this idea of the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and his slaves, and that’s not what you encountered. So your imagination started to expand, as well, at that point.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Yes. I expected resistance. I think most people — many people in the United States had believed that the story was true. The real opposition had been among historians who did not like the story, because if you have a man and suddenly give him a person that he’s lived with for 38 years and four kids, that changes the narrative of his life, and that means you have to deal with it. They can’t just be side characters. They have to be part of the story. So there was real resistance to that.

And I went to Virginia, and I’d give talks in Virginia, and I’d be sort of — “Oh, God, what is this going to be like? I’m in Richmond. I’m in Fredericksburg.” Or whatever. And people sometimes would come up to me with their own stories. Whites would come up to me with their own stories about their families that had been hidden, things that they didn’t talk about. So Southerners knew this.

Ms. Tippett: Right, because, as you say, this was an American life.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: This was an American life, and that kind of thing happened in the South. And it’s pretty clear that it did, and most Southerners understood it. But it’s the kind of thing that you know but you don’t talk about. Families have secrets; communities have secrets. And they whisper it, but they don’t talk about it, even though it’s apparent in the faces of African-American people who are all different colors, different hair textures, and so forth. It’s always been there. But it’s always some phantom traveling salesman or phantom person who came to visit one time. It was never anybody that anyone cared about. It had to be somebody who was off and that you wouldn’t have to write about. So the reckoning was actually saying, slavery was not just about making people work for no money. Slavery created a mingled bloodline between African Americans and whites, acknowledged and unacknowledged, but that shows the complexity, the tragedy in all aspects of the institution.

[music: “Kat’s Gut” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with the historian Annette Gordon-Reed, together with the artist Titus Kaphar.

Ms. Tippett: You also wrote in that same article — and I feel like this is something that people on all sides of the political spectrum were able to celebrate and acknowledge — that that election of a black president was just this magnificent moment. It was a stunning moment. And it said something. But you also said, “Racism is no easy foe.”

I wondered if what the election of Barack Obama did — if it was not inevitable that at one and the same time this remarkable thing would happen, given our history, that also it would surface all the unfinished business in our midst for us to really meet that, to be worthy of that.

And Titus, your work has covered so many subjects over the last years, but many people know the painting that you did after Ferguson. And, of course, also in these years, this phenomenon of violence towards black men and women especially, and Michael Brown and — we now have this list. But it is a similar phenomenon to what you described. I mean this had been happening in our midst all along, even as we patted ourselves on the back through Democratic presidencies and Republican presidencies, with white presidents and with a black president. And it’s kind of the iPhone that, as much as anything else, brought it to our attention. But it’s also something you’d lived with and, Annette, you’ve lived with, right? And we weren’t naming it.

Mr. Kaphar: No, in the black community, that was not a shock. That was not a surprise. Everybody knew that. I’ve been stopped at gunpoint by police officers when Bush was president. I was stopped at gunpoint when Obama was president. Going back to personal versus political, when Time asked me to make that painting, I wasn’t making — I was already working on a painting, because I had just had an experience with my brother in New York.

I was adopted when I was 15, but I still am very, very much in contact with my family. And my mother had sent my brother to stay with me for a little bit, because he was getting into trouble back in Michigan. And I was supposed to do my older-ly brother duty and talk to him about how he was getting in trouble and how he needs to stay out of trouble — it’s not a good time to be dealing with police; it’s prison now, it’s not juvenile hall.

My brother and I didn’t have a whole lot in common, at first. Started talking, day one, it was very clear to me that he was deeply interested in shoes and women, and that was it.

[laughter]

And the extent of our conversation was very limited, as a result of that. Day two — less women, more shoes.

[laughter]

And day three, something happened. The conversation opened up a little bit. And we started talking about things, and he started opening up a little bit. And he finally said to me, he said, “Hey, why don’t we go see some of your artwork in New York?” And I was shocked. He’s never really talked about wanting to see my work or anything like that. I said, “No problem.” Took him to New York. And I expected that we were going to be looking in galleries for about 10 or 15 minutes, and then we would move on and go get shoes.

[laughter]

I thought that’s what was going to happen. But we ended up going in and out of galleries for two hours. And he was just so excited about the artwork, stuff that was really conceptual and stuff that I thought, “This is too heavy for him. He’s not going to like it.” But he was deeply engaged by it. So as we left those galleries, after those two hours of walking —

Ms. Tippett: And so what year was this? This was just a couple years ago, right?

Mr. Kaphar: This was just a couple years ago. After we left the galleries, I said, this is my opportunity to talk to him. So we’re walking down 10th Avenue between 26th and 27th Street in New York, and I’m saying to him, “Listen, Mama’s very concerned about all the things that you’re getting yourself involved in.” And literally, as I’m having that conversation, an undercover police car speeds up to us. Police officers jump out of the car with hands on their guns and tell us to get against the wall and started demanding my ID and all this other stuff.

I say that to say, everyone in my community already knew that was happening. I wasn’t making that painting because I was trying to make some point. The only way that I’ve found that works for me to really work through these issues is to get into the studio.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Yeah. I grew up — in my hometown, it was very much known. There were many instances of people, police officers harassing individuals. One teenage boy was arrested and went into the precinct and was killed. Allegedly attacked someone, and he was shot and nobody ever figured out what was going on with that. I mean I’ve — it’s different, even though I think African-American women still have problems, certainly. Sandra Bland, those stories everybody knows. I was on a part of our book tour with my coauthor, and we were driving along one evening, and we were stopped. And it was not anything serious that was done, other than the officer asking me for my identification — I wasn’t driving. He was driving. And I was just thinking about the fact that I felt so different because he’s a white man. I mean in the first place, they asked for my ID. I doubt if I had been his wife, a white woman, that he would have asked for my ID. I wasn’t driving. And I teach criminal procedure. This is the thing that I teach my students.

[laughter]

And it was wonderful — I got to go back the next day and say, “Guess what happened to me. I got stopped. Oh, actually, my coauthor got stopped. I got stopped with him.”

And the notion that I would feel — if I had been with my husband, who is a black man, I would have been much more frightened, because I wouldn’t have known what would have happened. I knew they weren’t going to bother him. He’s there in his glasses and pullover sweater and a tie, and if you went to them and said, “Who is that?” they’d say, “That’s a professor.” I mean it was obvious what he was, not a drug dealer. But why were they asking me for my ID, other than that we were a racially incongruous couple? And true to form, I said, well, all right, it’s nighttime, you don’t know what’s going to happen. Just give him your ID.

Ms. Tippett: But this is the 21st century, right?

Ms. Gordon-Reed: You don’t know what’s going to happen. So I — you know, I didn’t have to give him my ID, but I did, because I didn’t want to cause any problems. That’s the only time I’ve ever been stopped, but you just think about the range of how race implicates, intrudes on every single thing that happens.

Mr. Kaphar: The thing that I don’t think that we think enough about — because the stop, obviously, is disheartening, is demoralizing. We all get that. What I don’t know that people understand is that when that’s happening, you feel less like a citizen. You feel like this country is not yours and that your rights are subject to somebody else’s whims. That’s the part that I think that we need to understand here, today — that when you make these sort of arbitrary stops, you are pulling folks outside of the conversation of our political structure more and more. And ultimately, they go, I don’t want to be a part of your thing, because it clearly has nothing to do with me.

That’s not what we want to do. That’s not what we want to do. And if that was the only bad thing that came out of that, that would be enough for us to just stop that practice.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Yeah. Exactly. No one was killed that evening, but as I said, it made me think about my relationship as a woman married to a black man, feeling different. Who knows what would have happened. And I have a son who I’ve raised in New York, and I have those feelings too. What happens? What happens when people talk to you like you’re a dog, and you’re talking to a young person, and you know that it’s provoking? But — you don’t feel like a citizen. And that’s what we’ve been grappling with since Jefferson’s time: Are African-American people part of “the people”? Are we actually citizens here? Malcolm X said, well, if you’re a citizen, why do you have to fight for your rights? I mean the citizen either has rights or not. Why are you fighting for them? And we’re always in that position.

Ms. Tippett: I’m curious about how you, as an historian, think about how the narrative starts to shift, right? — the narratives we prioritize, and how that changes. One of the things you’ve talked about with the research you did with Jefferson and Hemings’s families is that, as you said, this happened in the South. Everybody knew it. Everybody was part of it. But that was oral history, and that wasn’t the same as history. It feels to me like this — as terrible and shocking it is and that it continues to go on, this specter of violence and just what you’re describing, people not feeling like citizens — we’re also, I think, seeing this and naming this, not perfectly, not completely, but in a new way.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: But it depends — we’ll have to see what comes of it, because we still haven’t had — in the killings, in the shootings — indictments. People see it, and we’re shocked by it, and it’s to a point where now it’s almost — there’s sort of a backlash: “I don’t want to see anybody else get killed. I don’t want to see this anymore.”

It’s very hard to indict a police officer. We understand that people are doing a job that lots of people don’t want to do, and it can be a dangerous job. And part of the way that people get paid to do that is to give them discretion. Judges and law enforcement is given a great amount of discretion. But there are so many instances, you wonder when people will actually — we’re naming it, and we’re seeing it, what is the next step to try and figure out how to deal with this problem? How to reconcile or reckon, however we want to put it.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, reckon and repair.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Reckon and repair our relations among — we do have police officers. We need police officers. But we also need to have some sense that African-American people — a reality that African-American people are, in fact, citizens.

Ms. Tippett: Titus, you named something that I think is really important, and you talked about it in the context of your painting after Ferguson, which — was that called “Yet Another Fight For Remembrance”? But the fight to remember when an issue disappears from the media — and that when something disappears from the media, we should not all take that as permission to forget. And you bring that into your painting. Just talk a little bit about that, how you inhabit this dynamic.

Mr. Kaphar: My father has been in and out of prison for much of my life. My cousins are still incarcerated. One of my cousins died in prison. The community that I come from, this is not — I don’t have to try to remember not to forget. It’s just family.

When I wrote that, I was writing that for those for whom there is that possibility because that’s not where you’re from. It may not be your world. But in this moment, there’s been this compassion that I’ve seen from folks that I didn’t necessarily see it from before. And I’m saying, please, let’s not let that go away. We need to keep that in the discourse. So it’s not something that I feel like I need to work at, but I hope that as a whole, as a country, it’s something that we hold onto.

There’s a lot of issues that we have to deal with right now. And as we were going through the consortium this afternoon, just remembering all of the oppressed groups that are struggling with different things, it feels — sometimes it feels overwhelming, but I think it’s necessary to remind ourselves until we take that all on and stop dividing them and segregating them and — “This is the American Indian problem over here. And this is the African-American problem over here. And this is the immigration problem over here.” They’re all definitely separate issues, but what was really amazing about today was everyone coming together and saying, “OK, I can help with this. I can help with this. My organization does a completely different thing, but we can help in this way.” I think that’s when things really begin to change.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: It’s an amazing time. I mean Du Bois said that the problem with the 20th century would be the color line, but we’re still there in the 21st century, and now it’s at a global scale. This is not just — the ferment that we’re talking about now is not just here; it’s all over the world — problems of work, problems of inequality, the shifting alliances, and so forth. It’s a frightening time, but it’s also a time that if we choose to be, it could be a hopeful time.

Ms. Tippett: I think also about how we — one of the people I’ve interviewed is Mahzarin Banaji, who helped create the science of implicit bias at Harvard. So we did shift the color line in terms of laws, but we didn’t — yet, there’s a color line in our head, right? That’s what we’re reckoning with now. And we didn’t know that 50 years ago the way we know it now.

Titus, when I look at that painting, “The Myth of Benevolence” —

Mr. Kaphar: “[Behind]” “[Behind] the Myth of Benevolence.”

[Editor’s note: Mr. Kaphar misstates the title of his painting “Behind the Myth of Benevolence” as “Beneath the Myth of Benevolence.” It is corrected in this transcript for clarity.]

Ms. Tippett: “[Behind] the Myth of Benevolence,” which is — as you often do, it’s one painting on top of another. It’s Thomas Jefferson, but then the canvas is peeling away, and you see this image of a slave woman, and it’s an intimate image. In some ways, you could almost say that’s a picture of implicit bias, right, the contrast that we carry around — who we are, who we present to the world, and who we believe ourselves to be — and are, in some way — and then, also, who we are.

Mr. Kaphar: This painting was made after a conversation with — and this is a couple of years ago. We were sitting down, we were having a conversation, and she’s a schoolteacher; she was a schoolteacher for years, for 30 years. She taught history, AP History. And I love talking about history. And as we were sitting there talking about history, we moved on to Jefferson, and I said, “Fascinating individual. Fascinating individual.” And she said, “Well, what do you mean?” And I said, “Well, you know, the issues of slavery, but at the same time, this brilliant mind. Wow. Just complex.” And she said to me, “Well, there was slavery, but he was a benevolent slave owner.”

And I said, “I … I … I don’t know what you mean by that.”

[laughter]

And she didn’t respond to me. And so I sort of followed up, and I said, “I’ve never once ever heard anyone called a “benevolent rapist.” I’ve never heard that before. I’ve never heard anyone called a “benevolent kidnapper.” I don’t know what you mean. Could you please just clarify it for me.” She sat in silence for at least two or three minutes, and then that was the end of the conversation. And so I got up, and I left. I went to the studio and had to do something, and this is what came out.

[music: “Flow Part 1” by Terence Blanchard]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, more with Titus Kaphar and Annette Gordon-Reed. This episode is part of On Being’s Civil Conversations Project, an evolving adventure in audio, events, resources, and initiatives for planting relationship and conversation around the subjects we fight about intensely — and those we’ve barely begun to discuss. To learn more, visit civilconversationsproject.org.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, reckoning with history in order to repair the present. I’m with historian Annette Gordon-Reed and painter Titus Kaphar in a live event at the 2017 Citizen University National Conference in Seattle.

Ms. Tippett: Titus, you also tell a story about reading about George Washington and discovering the agony that he felt about slavery and the questions that that raised for you and the kind of agony it raised for you.

Mr. Kaphar: Yeah, I was saying this before. We were talking before, and I was just saying, I struggled academically in school. I was that kid that got kicked out all the time. I got kicked out of kindergarten, literally. My GPA in high school was .65.

[laughter]

And I was that kid. I was that kid. And when something clicked in my mind, I literally felt it. Something clicked in my mind, and I was able to see the world differently. I was able to engage texts differently. I felt obligated to start reading all the histories that I had ignored when I was supposed to be paying attention in school. So when I started making the work that I was making, I felt obligated to read more about American history. And I started at the beginning, with George Washington. And I had all of these preconceived notions. Some of them were right, but some of them were wrong. What I did not expect from the reading that I had done was in how much writing he had made it clear that this was a huge problem and that he thought that this was going to devastate the country, and yet he felt like he could do nothing about it.

That was the thing that was kind of surprising to me, as I read through some different journal entries and things like that — it was clear that he knew that this was wrong. Clear he knew it was wrong. Because there’s this thing that we do where we try to say, “Well, it was a different time, and you can’t really judge them based on our morals of today.” You can say that if you want to. It was clear that they knew that there was a problem with what was happening. There was a lot of equivocation that had to go on. There was a lot of decisions that had to be — there were a lot of excuses, but — that shocked me.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Yeah. And that was Jefferson too, talking about some of the most eloquent statements against slavery but not being interested actually — Jefferson was interested in something else. I mean, Jefferson was interested in the United States. He helped start a country, and that is what he focused on. We sort of know that it actually was going to work — [laughs] to a point — and he didn’t think, at the time — it wasn’t clear that it was going to, and so he focused all of his attention on that. We look back, and we’re interested in — rightly, I think — in race and slavery, but that was not his preoccupation. He knew slavery was wrong, and he said that. But what he basically was obsessed about was the United States of America.

Ms. Tippett: I think that the question of, well, what — so “George, if you had done something…” Right?

Ms. Gordon-Reed: I think George Washington — people castigate Jefferson, but the person who had the most moral capital, the person who could have — there were always people who hated Jefferson, so he was not a universally beloved figure. Washington, for the most part, was. If he had said something, I think he could have had the most influence, if he’d spoken out.

And in fact, one of Jefferson’s secretaries, who, when Washington died, and Washington did free his slaves — they were supposed to be freed upon Martha’s death — and this person was somewhat critical of him. He said, “If he had done something when he was alive, that’s the time to have done something.” I mean, glad that he freed the slaves, the enslaved people who were at Mount Vernon, but a president, a person with that moral capital, if he had spoken out, would have made, I think, a huge difference. Although, I don’t know that it would have made the Virginians give up their slaves right away. But I think it could have made a difference.

Ms. Tippett: So nobody in this room has the social capital that George Washington had then. And I don’t actually think any individual ever again will be able to have —

Ms. Gordon-Reed: No, they won’t.

Ms. Tippett: Right, we don’t have these kinds of generally universally respected places where everybody is looking and seeing authority. But an implication of that — actually, this could be the dream of democracy, right, that it’s back to each of us in our lives. And I wonder what each of you would want each of us to ask of ourselves.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: What I would like to see people do — and, I think, particularly, white people to do — would be to challenge one another on this question of white supremacy and racism. Black people can’t and should not have to convince white people that we are human beings who have a right to be on the earth.

[applause]

The only time we’ve made progress is when whites, a critical mass of whites say, “Enough of this. Whatever it is I’m getting out of going along, I can’t.” And people have done that. William Lloyd Garrison did it. Through the years, you’ve had people who did that. I would like to see more whites do that, because it’s demeaning, it’s not right for people to have to make the case that we are humans. And to the extent that your family members don’t seem to know that or your friends don’t seem to know that, I think that’s something that — that’s a conversation that has to take place among whites. And it has happened. It does happen, and we have made progress. But it should happen more.

Mr. Kaphar: I just want to piggyback on that for just a second. I think when you say, “We shouldn’t have to prove that we are human” — I think there’s probably people out here who probably think that that’s a form of hyperbole, probably think, “There’s no way in the world she actually thinks that there are people who do not believe that black people are human.”

Let’s not think about it in those direct terms for just a second. Let’s think about what happens to black people. So you may say, “Of course black people are people. I just said ‘people,’ didn’t I?” But when you think about what is going on — and again, I don’t even want — this is something I want to work on. I don’t even want to talk about it in that frame, because it’s not just black people. It’s not just black people. There are so many people who are treated as though they are not humans. I mean let’s forget about black people for just a minute, just a second, and talk about undocumented people in this country. Talk about not being treated like they’re humans. Let’s talk about indigenous people not being treated like they’re — treated like they’re not humans.

[applause]

So I just want people to know that that’s not hyperbole. Forget about what people say. Let’s talk about what their actions are and judge them based on those actions. And based on those actions, there are people who are still questioning that fact.

[music: “Plucky” by Atusi Assiv]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with painter Titus Kaphar, together with historian Annette Gordon-Reed.

Ms. Tippett: I don’t know if this fits, but Titus, you’ve got this project, “The Vesper Project.” And I’m just going to raise it, and if it’s a dead end, we’ll — but somehow it seems to me — so this is a person, Benjamin Vesper. Is he white?

Mr. Kaphar: That’s a very good question.

Ms. Tippett: You don’t know?

Mr. Kaphar: I didn’t say that.

[laughter]

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, no, I know. I just wondered. OK. But that he became obsessed with your painting and attacked and was destructive. But it seems to me that you hospitably engaged his psychosis. Is that fair? Would you say that?

Mr. Kaphar: That is fair.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] OK. And speaking of “the other” — and, I mean, it is a psychosis, right? This is when our brains are in primal mode, lizard mode. There’s something he wrote to you. He corresponded with you, and there’s something he wrote to you, talking about — he says, “Then the painting I’m looking at” — he’s talking about your painting — “reaches out and takes hold of me / Like the day the Indian Ocean woke up and decided to claim several thousand souls / I realize now that it was a trap / The lure was well placed / Just around a corner so I couldn’t see it coming / Maybe it called to me / I can’t say for sure now / But once I was in front of it I felt so alone.”

Somehow I feel like that — just this exchange and then also what you did with it is a bit of model. And it’s very messy. The whole thing is messy.

Mr. Kaphar: My work has always been about narrative, about stories and conversations with people. And I really feel obligated — I don’t know why, but I really do feel obligated to be that guy that’s willing to have conversations with people who I know don’t like me. That’s just my thing. I just do. And it’s hard sometimes. It’s really painful sometimes. It’s been more — usually, it’s hard. Recently, it’s been painful. It’s been really painful. Surprised at the things I’ve been hearing.

But I feel like if I can figure that out a little bit — I was talking, saying this a little bit earlier — if I can figure that out, if I can sit with an individual who feels very differently about the world than I feel, and I can get to some place, get any place, that I will have touched on a piece of the solution that we’re all looking for in the country. And so that’s sort of my motivation for putting myself through this crucible over and over and over again. And it’s the same with that.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: I have a friend who is always exasperated with me when I answer emails from people like that, because I have the same kind of urge to do that, to actually — and not all the time, but sometimes we actually do get to a point where the person will begin to back down and will begin to open up. And even though that’s just one individual, I see that as something of a victory, in a way, rather than just totally turning off and not — I mean, some people are so nasty, I don’t do that. But if I have any sense that the person is questioning — because a lot of times people write to you, or they’re like that, and they’re kind of lost. And they’re disturbed by something. And they present themselves as being very, very clear and set, but they’re really not. They’re really questing, in a way.

Mr. Kaphar: Absolutely.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: And a conversation that you can have with them, you may not come to a total agreement, but they are in a different place. And that’s kind of why I wanted to write, because I wanted to be able to reach people — and reach those kinds of people as well, not just the people who are saying, “Oh, you’re great, you’re great. Everything you’re doing is wonderful,” but people who are questing in that way.

Ms. Tippett: Where do people who mean well go wrong?

[laughter]

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Let me count the ways? I mean…

[laughter]

Mr. Kaphar: Look …

Ms. Gordon-Reed: We all mean well.

Mr. Kaphar: There’s a lot of ways to go wrong, attempting to mean well. But it’s better to go wrong, attempting to mean well, than go wrong not attempting at all.

So I have compassion for that, right? It happens all the time — people ask these questions, you’re like, “Wow. OK, all right. Let’s sit down. We’ll have this conversation.”

I was sitting down, for example, with someone who believes very differently from me about welfare. And we were talking about welfare, and they were just railing on welfare and how no one in this country should have welfare, and it’s a waste of money, and this and this and that. And I said, “Yeah, my mother was 15 when I was born. If we didn’t have welfare, I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you.” And I realized in that moment I was the only person, the only person that this individual had ever had a conversation with who was actually on the other end of their critique. And they actually stopped and said, “Really? You?” And I said “Yeah, yeah.” So I have a lot of compassion for going wrong. But let’s just try.

Ms. Tippett: OK, you don’t — you’ve got too many, your list is too long? [laughs]

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Oh, where do people go wrong? People go wrong, I think, in not — well, in my area, very often seeing people like Jefferson as a god, in a way, somebody who was superhuman — on both sides. I’m not just talking about people who revile Jefferson; people who love Jefferson are not dealing with a human being, dealing with an abstraction and don’t see the foibles and the frailties of a person who was human. So I think people go wrong on both ends by not recognizing the humanity. As a historian, history is not just about writing about people that you like. It’s about people who were important, who did important things, and to try to illuminate their lives in a way that makes that plain to readers: Why is this person important? All the different roles he played during this time period — and to see the strengths but also to see the vulnerabilities.

As an African-American person, people say, “Well, how can you write about this figure with any degree of sympathy?” or whatever. But first place, there’s the fact that he lived a very, very long time ago. So there’s distance. But it’s not, as I said, about your personal feelings about it. It’s about the importance. This is someone who was at the center of American life, who crafted words that we consider to be our creed, American creed. And whether he failed or not, that is something that was put there — that every group of people who tries to make a place for themselves in the United States, in American life, that they use it. And flaws and all, that is important. So I think not seeing the humanity — making the person larger than life, superhuman, or evil incarnate — is not the way to go.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. In general, I think. [laughs]

So Annette, here’s something you wrote:

“The chief value of having read lots and lots of biographies, and having seen multiple families in action in them, is that whenever anyone insists that a particular thing could not have happened, or a given situation could not have obtained in any domestic setting, I can think of a half dozen instances where that very thing, or something akin to it, or something even more bizarre, happened in a family.”

[laughs] And I’m thinking about the American family too, right? So does this also work for good turns? Could we surprise and outdo ourselves by the way we walk through this moment we inhabit?

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I do think that there will be alliances formed that you could not have imagined would be formed.

Ms. Tippett: And that might not have had their — felt their reasons to form.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Might not have felt their reasons to do it. It’s a very, very up-in-the-air moment. And I don’t think it’s — it’s reason for exasperation, in many ways, it’s a reason for uncertainty, because it’s a new thing. We’ve never done this. As I said, we’ve never had a president like this, a person who is really not a part of a party, a part of a system, who’d been through all of this. So it’s new territory that we’re in, and I think we can surprise ourselves. I mean it’s a big country, a lot of talented people, and I think a lot of people of goodwill. It’s easy to focus on the negative, but I do think it’s — I think that there’s a reason to be hopeful about it.

Ms. Tippett: And all the social fracture that we’re dealing with would have been there the day after the election, whoever had won.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Oh, whoever won.

Ms. Tippett: I mean, it came — it was that whole year that brought it, and the years since.

Can we surprise ourselves?

Mr. Kaphar: Absolutely. So I went to this Creative Capital event, and at the event, I gave a talk. And after I gave the talk, I watched Cassils, Heather — transgender artist who is — if you don’t know the work, you just need to look it up. Cassils came and sat with me at the table, and we started talking. And I was talking about issues of incarceration, and Cassils was talking about the number of transgender women who were killed at the beginning of that year. And we were just going back and forth and going back and forth about stuff. And we decided, “You know what, we need to work together. We need to make a project together and figure out this. This is what I’m going to do. I want you to teach me through your content, and I’m going to teach you through my content. And then we’re going to produce an exhibition together.”

And Cassils is my dear, dear friend now. It has completely opened my eyes, again, to this thing I was saying before about not dividing us up in this way but bringing us together and say, “Let’s solve the whole problem. Let’s try to solve the whole thing at once, see what we can do.”

Ms. Tippett: This is another way that we are very strange as creatures, isn’t it, that a crisis also becomes this moment of — it opens generative possibilities that weren’t there before, as well.

Ms. Gordon-Reed: Absolutely.

Ms. Tippett: Well, Annette Gordon-Reed, Titus Kaphar, thank you so much. And thank you for what you do in the world.

[applause]

[music: “Shine” by The Album Leaf]

Ms. Tippett: Annette Gordon-Reed is the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History at Harvard Law School and a professor of history in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. Her books include the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, and Most Blessed of the Patriarchs: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination.

Titus Kaphar lives and works in New Haven, Connecticut and has received numerous awards, including the Artist as Activist Fellow from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, and the 2018 Rappaport Prize.

Special thanks this week to Citizen University Founder Eric Liu, also to Jéna Cane, Ben Phillips, Sasha Summer Cousineau, Taelore Rhoden, Cary Wakeley, Tom Stiles, and all the great people at Citizen University.

Staff: The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Damon Lee, Suzette Burley, Katie Gordon, Zack Rose, and Serri Graslie.

Ms. Tippett: The On Being Project is located on Dakota Land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It’s distributed to public radio stations by PRX. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections