Aracelis Girmay

Consider the Hands that Write this Letter

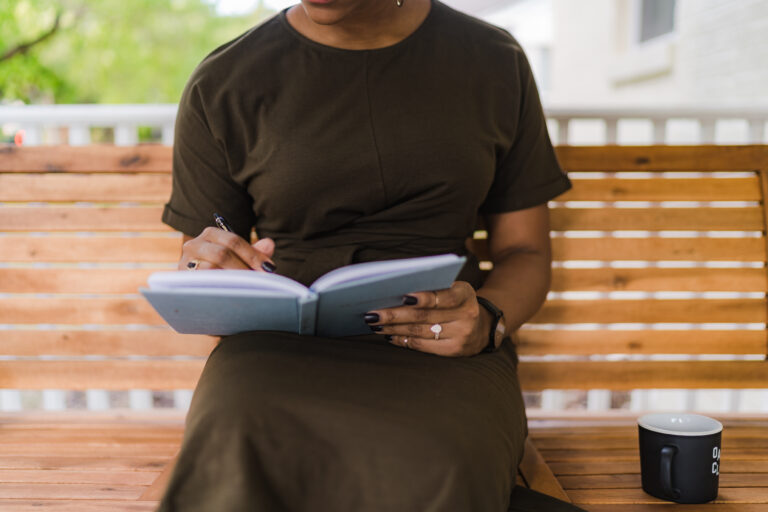

When you’re writing by hand, where is your other hand? What story is the space between your two hands — your dominant hand and non-dominant hand — telling?

This poem considers the posture of the body when writing: writing a letter, writing a note, writing a poem. The poet pays attention to hands — when dancing, when speaking from the heart, in prayer. This poem invites the listener to slow down, to listen to the stories the body is telling by how it’s held in small moments.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Aracelis Girmay is originally from Southern California and now lives in New York. She is the author of the poetry collections Teeth, Kingdom Animalia, and The Black Maria. Her essay "From Woe to Wonder" can be read in the Arts & Culture section of The Paris Review (June, 2020). Girmay recently edited How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton and she is on the editorial board of the African Poetry Book Fund.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the things I love about reading poetry is that somebody, somewhere, the poet sat, usually by themself, and wrote this alone, maybe by hand, first, before it was printed. And the intimacy of that, the musculature of that, and the time that that took and the energy it took, moves me.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: “Consider the Hands That Write This Letter” by Aracelis Girmay: and she credits this poem being written “after Marina Wilson”:

“Consider the hands

that write this letter.

Left palm pressed flat against paper,

as we have done before, over my heart,

in peace or reverence to the sea,

some beautiful thing

I saw once, felt once: snow falling

like rice flung from the giants’ wedding,

or strangest of strange birds. & consider, then,

the right hand, & how it is a fist,

within which a sharpened utensil,

similar to the way I’ve held a spade,

the horse’s reins, loping, the very fists

I’ve seen from roads through Limay & Estelí.

For years, I have come to sit this way:

one hand open, one hand closed,

like a farmer who puts down seeds & gathers up;

food will come from that farming.

Or, yes, it is like the way I’ve danced

with my left hand opened around a shoulder,

my right hand closed inside

of another hand. & how I pray,

I pray for this to be my way: sweet

work alluded to in the body’s position to its paper:

left hand, right hand

like an open eye, an eye closed:

one hand flat against the trapdoor,

the other hand knocking, knocking.”

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I love this poem, in the way that it’s a poem about the body, and it’s the poet, Aracelis Girmay, wondering, what posture will she hold in the body, when it comes to thinking about her craft? The poem, towards the end, moves toward its truest purpose, which is really a poem about prayer and focus and intention: “& how I pray, // I pray for this to be my way: sweet / work alluded to in the body’s position to its paper.” And this is her work, to be a poet, and she’s wanting her body to correspond to the work of poetry that she’s doing, the right hand holding the pen, the left hand open, one hand open, one hand closed; this joint movement of in and out that’s happening in the work of the poet. They’re absorbing, and they’re giving out at the same time.

This poem has resolved itself into finding ways within which openhandedness and closedhandedness can be part of a dance together. She literally describes a dance, earlier on: it’s “like the way I’ve danced / with my left hand opened around a shoulder, / my right hand closed inside / of another hand.” There’s openness and closedness happening all the way. And she’s described her craft as a poet. And she ends on this image of a trapdoor. And trapdoors are so intriguing, but also frightening; it depends. If you’re locked underneath one, well, then, it can be particularly frightening. If you’re about to open one, well, then, maybe it’s exciting. And so the poem finishes with “one hand flat against the trapdoor, / the other hand knocking, knocking.”

That seems to imply, perhaps, that one hand is on top, holding it down, and the other hand is on the bottom, knocking to be left out, and the door itself, perhaps, is the place in which the poetry is written; that she holds herself in this remarkable tension between openness and closedness, between the creative moment and spontaneity and the discipline to write that down, and that that’s the place where creativity comes from her. Something is trying to get out, and another hand is trying to craft it into form.

[music: “Careless Morning” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: This poem has a way within which there’s something that’s held in the space between two opposite movements. And the opposite movements are like having one eye open, one eye closed, a hand knocking, and a hand holding the door closed, a hand putting something down, and something else taking something up, a fist open against the heart, and a fist closed, holding a pen or a spade. In a way, I think Aracelis Girmay sounds in this poem like an echo of the famous child psychoanalyst Winnicott, who speaks about children playing hide-and-seek. And he says, it’s a joy to be hidden and a disaster not to be found. That joint movement that we find creativity in, the going out and the coming in, the giving, but the holding back, the surrendering yourself, but yet, the watching of yourself surrendering yourself. And it seems to be that creativity is often held in these in-between moments.

Aracelis Girmay doesn’t make reference to Winnicott in this poem, but I do think that she and Winnicott are circling around that same thing, that desire to open that comes together with that desire to close, and that there’s some sweet moment in between both, where something creative and transcendent can emerge.

The opening line is “Consider the hands that write this letter.” And is that a letter like ABCDE, or is it a letter like, “Dear friend, I’m writing to you to tell you this great news”? And letter writing does seem to be something of the past. I grew up loving writing letters and loving receiving them.

And there’s something about getting something in somebody’s handwriting and deciphering it, and thinking about the time that it takes to handwrite a letter and then to receive that. It’s different than getting a text message. It’s different than getting an email. It’s different than getting a voicemail. Getting a letter displays something about time, and there’s something physical about it, too: you can hold it in your hand; there’s the choice of the paper, the choice of the ink. In “Consider the hands that write this letter,” Aracelis Girmay invites us to think about whose hand is behind the question here.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Beyond the question as to whether this is a poem by a poet for poets, this is also a poem about the body. And it invites people, I think, to think about the posture you hold in your body when you do your work — and even, also, not only when you do your work; simply when you write. If your left hand is writing, what’s the right hand doing, or vice versa? And it asks us to pay attention to the posture of the body in a very ordinary thing, like writing, and then, perhaps, to ask questions about everyday posture in other things we do, too. Lots of people, of course, write on the computer or a phone, these days. But still, we write even in small moments, scribbling a note on a post-it to a colleague or to remind yourself of something. I write on my hand all the time, or write along the margins of a book, or write a shopping list. And in all of those postures, this poem is asking us to slow down and to pay attention to the way that you’re holding your body. And how can you give a message to your body about your intentionality, in the way that you hold your body in those small moments?

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: “Consider the Hands That Write This Letter” by Aracelis Girmay: this poem is shaped “after Marina Wilson”:

“Consider the hands

that write this letter.

Left palm pressed flat against paper,

as we have done before, over my heart,

in peace or reverence to the sea,

some beautiful thing

I saw once, felt once: snow falling

like rice flung from the giants’ wedding,

or strangest of strange birds. & consider, then,

the right hand, & how it is a fist,

within which a sharpened utensil,

similar to the way I’ve held a spade,

the horse’s reins, loping, the very fists

I’ve seen from roads through Limay & Estelí.

For years, I have come to sit this way:

one hand open, one hand closed,

like a farmer who puts down seeds & gathers up;

food will come from that farming.

Or, yes, it is like the way I’ve danced

with my left hand opened around a shoulder,

my right hand closed inside

of another hand. & how I pray,

I pray for this to be my way: sweet

work alluded to in the body’s position to its paper:

left hand, right hand

like an open eye, an eye closed:

one hand flat against the trapdoor,

the other hand knocking, knocking.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Consider the Hands that Write this Letter” comes from Aracelis Girmay’s book Teeth. Thank you to Northwestern University Press who gave us permission to use Aracelis’ poem. You can find a link to the poem in our show notes, along with Pádraig’s guiding question for this episode.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.