Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

What If We Get This Right?

Amidst all of the perspectives and arguments around our ecological future, this much is true: we are not in the natural world — we are part of it. The next-generation marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson would let that reality of belonging show us the way forward. She loves the ocean. She loves human beings. And she’s animated by questions emerging from those loves — and from the science she does — which we scarcely know how to take seriously amidst so much demoralizing bad ecological news. This hour, Krista draws out her creative and pragmatic inquiry: Could we let ourselves be led by what we already know how to do, and by what we have it in us to save? What, she asks, if we get this right?

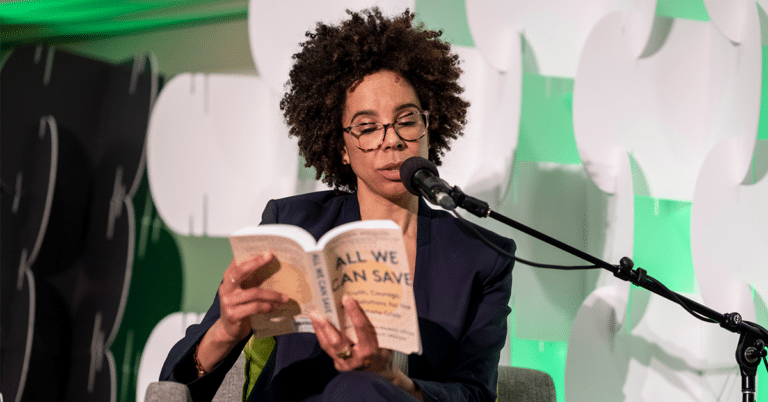

Image by Gilberto Tadday / TED, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is a marine biologist, and co-founder of the Urban Ocean Lab, a think tank for coastal cities. She’s one of the creators of the podcast, “How to Save a Planet,” and she co-edited the wonderful anthology All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. She’s also the co-founder of the All We Can Save Project. Image: Marcus Branch

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is a next generation marine biologist. She loves the ocean. She loves human beings. And she’s animated by questions emerging from those loves and from science, which we scarcely know how to take seriously amidst so much demoralizing, bad ecological news. This hour, we join her creative and pragmatic inquiry: can we let ourselves be led by what we already know how to do, and by what we have it in us to save? What, she asks, if we get this right?

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. I interviewed Ayana Elizabeth Johnson before a small audience at the 2022 TED conference, in Vancouver, Canada.

So Ayana, you and I met, as one does, on Twitter, and it’s so lovely to experience you in all this dimensionality and flesh.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: Yes, at least three dimensions.

Tippett: [laughs] That’s right.

So I will formally introduce you. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is a marine biologist, a policy expert and writer, and a Brooklyn native — I think that’s an important part of your credentialing.

Johnson: That is an important credential.

Tippett: She is cofounder of the Urban Ocean Lab, a think tank for coastal cities. She co-created Spotify-Gimlet’s podcast How to Save a Planet, on climate solutions. She coedited this beautiful climate anthology, which I had not discovered until now, and I so recommend it: All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. And also, you’re cofounder of the All We Can Save Project, which I recommend that people look up online. I love how you stress, in the description of that work, that you’re nurturing the “we” in that “all we can save.”

Johnson: People mistitle that book all the time, as “All You Can Save,” and I’m like, you’ve already entirely missed the point of the book. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] And I have also been fortunate to read a bit of a book-in-becoming, a manuscript, which — and I feel very fortunate, and I’m not going to quote from it too much here, because it will come out, and you can all read it one day, but: “what if we get it right?” What if we get it right?

And we live in a species moment, is how I think of this. It was probably true, pre-2020, but it is clear, post-2020. And I believe that underlying every grave and wondrous potential that we have as a species, and ratcheting up the panic that leads us away from rising to our highest human capacities, in every sphere of our life together, each of us knows and feels the disarray of the natural world at a cellular level, in our bodies. What is true is that we are not separate from it. It’s not even so much that we are in it — we are of it.

Johnson: We are one of 8 million or so species on this planet.

Tippett: We are of it. And so to me, an undergirding question for us, in this generation in time, is how to carry and reestablish that belonging amidst the alienation of the way we’ve been living. And nothing less than a transformation — which is what you bring home — of who we’ve been and how we’ve been living is needed. But how to begin?

Johnson: Where do we begin?

Tippett: Where to begin? And I want to read something — this is from your book.

Johnson: The book that does not exist yet.

Tippett: The book does not exist, the book-in-becoming.

Johnson: My editor may or may not be in the room, being like, Tell me more about this book. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] You write: “My perspective is that of someone brimming with juxtapositions. I am a trained scientist, who always intended a career in policy. I am the daughter of a practical schoolteacher and a wistful artist. I am cold New York winters and Caribbean heat. I am working-class and Harvard. I am Black and white. I am urban and smitten with wilderness. I am proof of the American Dream and proof that it is all too rare.” And then you write: “These are not dichotomies, but currents.” So just an observation as we start — I feel like the way you hold all of this, these “not dichotomies but currents,” in your person, in your body, is part of what helps you be a teacher and a bridge person and an explorer in this vast realm of crisis and promise that is existentially before all of us.

Johnson: I’d like to think that’s true. [laughs] I mean, I think, in this species moment, as you call it, it is this incredible time in human history where we all have to figure out how we’re going to show up, how we’re going to be helpful, because the world is rife with any number of dangers and injustices and trends going in horribly wrong directions. And one of the major things that I was told over and over again as a child, it was very much, Yeah, you can be whatever you want. Absolutely, go and be a marine biologist. That sounds reasonable.

So I think the lesson that I was taught was, you have to give back — you know, that same motto, “To whom much is given, much is expected.” And even though I didn’t come from a family with wealth or any extra resources, we had enough, and I had an incredible wealth of opportunities and experiences. And so while my parents made it clear that I was welcome to explore as many doors as I wanted, it was very clear that I needed to figure out what a life of service meant, and they helped me explore that for myself.

Tippett: Let’s ground this in the origins of your passion for the ocean.

Johnson: I mean, how do you not love the ocean?

Tippett: Well, right. Well, I think that’s something that — so Key West, Florida, summer of 1985 —

Johnson: I was five, for people who can’t guess my age from my voice. [laughs]

Tippett: You were five, it was a rare vacation that your whole family was on, and you see a tropical reef through the floor of a glass-bottom boat. And it’s really clear to me that you — that memory is in your body, and it propelled you forward, through the rest of your life. But would you take us there, to that experience?

Johnson: So my dad was Jamaican, my mom grew up on Long Island. My parents had this super strong sense that the job of a parent was to equip your child with the skills that they would need to navigate the world. And so that was the summer that they decided it was time for me to learn how to swim, and we went down to this little bed and breakfast in Key West, Florida, with what I remember to have been an enormous pool, which is probably, for scale of a tiny five-year-old, a normal-sized pool. And then there was this moment on a glass-bottom boat. And to see a coral reef for the first time, and to see all of these magnificently colored fish swimming around, and to see this literal window into this other world — I was just in awe.

And it’s this, like, whole city that’s happening down there, right? It’s not just these little sections where all the fish are the same. It’s this super vibrant and dynamic alternate universe — this ecosystem. And I just — I had a lot of follow-up questions, [laughs] during that initial trip.

Tippett: And then I’m also curious about the origins in you of this question, what if we got this right?, because obviously, there had to be other observations made after that initial falling in love.

Johnson: I think when the thing that you love is threatened, the natural reaction is to try to save it. And I fell in love with Caribbean coral reefs right as they were starting to crumble.

Tippett: What came to mind for me is the conversation I had with Sylvia Earle, who also has a great lineage at TED. And I was just thinking about you being of a very different generation — I mean, for her to be a woman in the field, and for you.

Johnson: Oh my gosh, what a pioneer.

Tippett: And for you, also — I mean, I just copied out some of what she said to me. And her pointing out — I feel like when you tell your story of seeing the fish, we do kind of remember that that — I mean, that’s a very universal experience, the fascination, the delight of a child.

Johnson: I mean, being a marine biologist is like, a really common dream job. I’m just extremely stubborn. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] That you grew up and held onto it. And she talked about how we’re so fixated on outer space, and what she called the ocean is inner space, but also, that in the last half-century in which she built her career and that you’ve entered this field, she said it’s been a time of revolutionary change in terms of what we know: that we didn’t know of the great mountain chains; the hydrothermal vents; the existence of life in the deepest sea. It wasn’t until 1960 that people descended to the deepest part of the sea, and we discovered tectonic plates. But you are coming into the field on the heels of that revolution.

Johnson: Yeah, and with a very different motivation. I mean, I think her generation was — they were explorers.

Tippett: Explorers.

Johnson: They were pioneers. They’re like, what is even down there? How do we —

Tippett: Aquanauts.

Johnson: Aquanauts. How do we understand this? And then: Oh [bleep], this is in trouble. And they all became conservationists, right? We saw that same professional transformation with Jacques Cousteau.

But I didn’t really grow up looking to their work. I didn’t really watch very much TV. So many people I went to school with who were a bit older than me were inspired by Cousteau. And I was inspired by having this understanding that ocean conservation is a matter of cultural preservation; being the daughter of a Jamaican and thinking about people all around the world in coastal communities, who depend on the ocean for their food security, for their livelihoods, for their cultures, that if we lose the health of ocean ecosystems, we lose something much, much greater than the way it’s often framed in conservation, as an issue of biodiversity, more technically. And it’s really just — for me, it’s like, as much as I love fish and octopuses and kelp and all these things, it’s really about people, why I do this work.

[music: “A Little Powder” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson.

[music: “A Little Powder” by Blue Dot Sessions]

And that’s an interesting point, too, isn’t it, that we — you’re right, the ocean conservation idea was all about the creatures in the ocean that could be saved.

Johnson: I mean, I want to save the creatures, too. [laughs]

Tippett: You do, I know. I know, I know. I know. Well, so I really — let’s go there. Let’s really get into how you investigate this as a scientist. So here are three areas that I learned you work in, and I want you to explain to me what they mean. Marine spatial planning is one.

Johnson: Ooh, that’s a good one.

Tippett: What is that?

Johnson: So marine spatial planning, also known as ocean zoning, which is maybe a more obvious definition, it’s very similar to the way we do zoning on land, where you’ll have industrial, agricultural, residential, and park types of areas, and you actually have places where you do things and places where you don’t do things. But the ocean has been, for most of human history, very much this open access, shared resource that’s just been plundered by whoever could get there first with the highest-tech equipment, whatever that meant at the time.

And that hasn’t gone that well. And so this idea that we could make a plan, a marine spatial plan, an ocean zoning map for deciding what should happen where, and when, and how to reduce the conflicts between different uses, where things can harmoniously coexist; how to make sure we’re not putting shipping lanes where whales are trying to migrate; and we’re thinking about where offshore wind energy should be sited and where regenerative ocean farming should happen and where fishing should happen — all these things need a place. And it’s much more helpful for industry if they have some certainty about the regulatory framework within which they’re trying to develop their business plans.

Tippett: It also just feels so elemental. I mean, it feels incredible that this didn’t happen until …

Johnson: I know. It still hasn’t happened, in most places.

Tippett: “Policy placebo effect in conservation.”

Johnson: Ooh, that’s a deep cut, Krista.

Tippett: Is it sexy? [laughs]

Johnson: [laughs] Yes, almost as sexy as implementing climate solutions. The policy placebo effect, so this came out of a paper that I was sort of a minor coauthor on, which was based on this marine spatial planning project on the island of Montserrat, in the Caribbean. And a lot of surveys were done to understand: people in the community, how were they perceiving different ocean policy options? How were they perceiving the health of their resources?

And one of the most interesting results was to learn that people assume that fish populations are healthier, basically right after you pass a law to protect them — which is just impossible. They can’t make babies that fast, right? And so there’s this placebo effect where people just assume that once you pass the law, that everything’s going to be OK. And this is actually a huge problem with ocean philanthropy, too, is that people want to pay nonprofit groups to do the work to establish protected areas, but not to maintain them, not to enforce them, not to monitor them.

Tippett: [laughs] Don’t you think we do that with laws that have to do with human dynamics, as well?

Johnson: I mean, humans are sort of a mess, aren’t they. [laughs]

Tippett: Yeah; yeah, OK.

And so then you’ve done a lot of work on collaborative research between small island states, and of course, this gets you back to your Jamaican heritage. You spent a decade working with fishing communities in the Caribbean. And what I’d like to know is what you learned there, from them; how that formed everything you do now.

Johnson: Oh man. I think it just made it less theoretical. And so I spent a lot of time drinking beer with fishermen. I, for months, was driving around with a cooler full of beer and sodas and snacks in my trunk and a bunch of folding chairs, and I had this survey that was, I don’t know, 200 questions long, and I would just be like, Tell me everything, I’ve got time — and having hundreds of hour, two-hour conversations, with fishermen on Curaçao, on Bonaire and Barbuda and Montserrat.

I had sort of become a bit too practical, a bit too cost-benefit analysis, a bit too theoretical about the fact that these are people trying to feed their families. These are people who, fishing is not a job, it’s a way of life, it’s a culture. And I just hadn’t been sensitive enough to the realities that folks were living in these different communities. And so it was really important for me to hear, out of the mouth of a fisherman — there’s a 15-year-old fisherman — he was the youngest one I interviewed — part-time; he was still in school. And the way he described the effects of overfishing was, it was very much — he grew up in this strong oral tradition, and most fishing communities have a pretty strong oral tradition of “the biggest fish” stories, right? And he said they used to show the size of the fish they’d caught, vertically. And he put his hand over his head. He’s like, and now we show the size of fish we catch, horizontally. And he put his hands the width of his shoulders.

And that is just a complete transformation in what these ecosystems look like and how hard it is to make a living.

Tippett: There’s — I think this is an article you wrote in the Sierra Club — you say, “[C]ontrary to this adage ‘there are many fish in the sea,’ there are in fact not many fish in the sea.” [laughs]

Johnson: Not that many fish in the sea, relatively speaking, yeah. That essay was published in Sierra magazine but was an essay I wrote for an anthology called Black Futures, edited by Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew, where I wrote about this intersection between ocean conservation and social justice, because I feel like we don’t talk about that enough.

Tippett: So that article — to come back to this idea of juxtapositions — there is a litany of doom, which is telling truth. The oceans have absorbed 90 percent of the excess heat created by burning fuels, sea levels rising, destroyed coastal ecosystems, entire ocean polluted, plastic epidemic, and everything you’ve just been talking about. But for you — and for you — the work that you’re doing and that you’re inviting all the rest of us to do is to hold that truth-telling — a seriousness about that, a seeing — together with wonder and joy, and those things going hand-in-hand with justice and regeneration. Just talk some about that and how that clarity and that energy — because it really is an energy in you — has evolved.

Johnson: My Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Jeremy Jackson, studied Jamaican coral reefs as they were in their decline. And what he said was, he doesn’t want to write an ever more refined obituary for the ocean. And his wife, Dr. Nancy Knowlton, then started this Ocean Optimism project, [Editor’s Note: Ocean Optimism was co-created by a group of scientists, journalists, and environmentalists: learn more here.] where the whole thing was about, what are we going to do? Where are things working? What lessons are we learning? What are the initiatives that we should be replicating around the world?

And that was certainly a major influence on me. I’ve always been focused on solutions. I have this extremely practical approach to most things — I’m like, OK, who’s doing what? What’s the plan? Like, let’s not talk about feelings so much; let’s figure out what’s next. And so that is the vibe that I’ve tried to take into my work as it’s broadened from oceans to climate more generally, is we have most of the solutions we need at our fingertips, for all of these climate challenges, whether it’s agriculture or green building retrofits or bike lanes or composting or wind energy in the ocean or farming seaweed or whatever. We know how to do this stuff. We just have to do it. And so figuring out how we can welcome more people into this work, get people excited, help them find where they fit, is really where I’ve been focusing my yammering energies, these days.

Tippett: You also use the word “love” a lot, just as every — I mean, recently I interviewed Colette Pichon Battle, and I know you heard that, because I saw you on Twitter.

Johnson: She’s a gem.

Tippett: But — well, I don’t know, I think you’re roughly the same generation, and —

Johnson: Although she’s so wise …

Tippett: She’s incredible.

Johnson: … that I can’t gauge her age.

Tippett: The Gulf Coast of Louisiana — you’re wise, too. But no, but I think that I hear you speaking the same language — and other people who I feel are actually pushing this forward and who actually know exactly how bad it is — and it’s this insistence on loving what it is we have to save that allows —

Johnson: Loving the future.

Tippett: Loving the future.

Johnson: Yeah, I mean, the most depressing thing I can think of is to just watch the world burn and crumble before my eyes while I just wallow in self-pity on the couch. Right? So I don’t have any delusions that I can “save the planet,” but you’ve got to try to do your part.

And that’s how I think about all of this. We know what we’re supposed to do, in that same way that you were describing we know that it’s wrong right now. We know that things are out of balance, on a cellular level. We can feel that sort of friction, with the way that we move through the world. I mean, I dare you to stand in a redwood grove and not be humbled, or to dive on a coral reef and see even just the glimmer of its former magnificence and have some respect for these ecosystems and the fact that we are sharing this planet.

So I think that climate communication has focused too much on the problem. I will admit, I don’t read the details of every UN climate report, because I know the summary is, it is worse than you thought, it is happening faster than you thought, and we really need to get our act together. And I focus on the getting our act together part, because I think that’s the pivot that we need right now. We have more than enough information. I’m grateful for the science, and it’s helping us make more nuanced and clear decisions, but the broad strokes that everyone needs to pitch in, have been there for a long time.

Tippett: I would like to offer — so I invoked Sylvia Earle. And the other two people that came to mind as I was getting ready to interview you were Albert Einstein and John Lewis. [laughs]

Johnson: What? [laughs]

Tippett: In this way —

Johnson: Did not see this coming at all. Very curious how these thoughts are connected.

Tippett: I think that this question, this question that you’re asking, this what if question — what if we get this right? — I think that is more of a contribution than I’m sure you even realize — that formulation. Einstein asked this what if question about pursuing a beam of light at the speed of light: what would happen? That was the beginning of him walking into his discoveries.

And John Lewis, when I sat with him in Montgomery — he lived as if. He said, what if the beloved community is already real? And we have to live as if. And so I think that this kind of what if question that you’re asking is a tool for social transformation.

Johnson: Well, that would be amazing, if it were true. We’ll see. I mean, yes, this is the working title of the book that I’m writing, What If We Get It Right?, because I feel like so often — I mean, the climate news is dire and depressing. And the amount of work that needs to happen, the transformation that needs to happen, in terms of everything — agriculture and buildings and industry and electricity and transportation and all of it — that’s a lot of change. And humans are not always super stoked on change when we don’t know what the outcome is going to be, for us, for our communities, for our livelihoods. And so that’s —

Tippett: And it’s hard. It’s a hard time in many ways.

Johnson: It’s a hard time in so many ways. And so to think about trying to offer that question — what if we get it right? What if we charge ahead with all the climate solutions we already have? — what kind of future do we get? Show me that it’s worth it. Show me this is worth the effort. Show me examples of where this is already happening. Show me that there’s a place for me in the future, after all this change.

[music: “Chilvat” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Ayana Elizabeth Johnson.

[music: “Chilvat” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with next generation marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. She is animated, in science and in public life, by questions we rarely take seriously amidst terrible ecological news: could we let our love for all that we can save lead us? And what if we get this right? We sat together with a small audience at the 2022 TED Conference in Vancouver, Canada.

I thought it was interesting that you said, on the podcast you did with Alex Blumberg for Gimlet, that you like to ask guests to describe what the future would look like if we get things right on climate. And you said that very few responses made the cut.

Johnson: Yeah, because we don’t talk about it enough. So people somehow are not prepared for that question with a level of detail that makes it interesting to talk about on a podcast.

Tippett: I know, but what that also means that we’re not even putting our imagination towards it. This needs creativity, too.

Johnson: Oh yeah, absolutely. I mean, that’s something that Naomi Klein talks about a lot, is how we are sort of in this moment where imagination is one of the most valuable things we can bring to the table. And a failure of imagination means a failure of the spectrum of futures that are available to us. And I just, I like to think of — so I remind myself and others that there is still such a wide spectrum of possible futures, and we do get some choice in which ones we have. We’re not going to be able to take some sort of time machine backwards to a perfectly pristine planet, when there’s 8 billion or something people on the planet. But we can have any number of possible options. And so, while I’m not a fan of hope as a guiding principle, because it by definition assumes that the outcome will be good, which I know is not a given, I am completely enamored with the amount of possibility that’s available to us. So that’s the word that I try to embrace when I think about what if we get it right, is how much possibility remains.

Tippett: Something that I think about a lot is —

Johnson: I guess I have to finish writing this book now. [laughs]

Tippett: Yeah, you’re absolutely — you have to be committed to it. We’re all waiting.

Johnson: I will say that I think the thing that I’m excited about, about this book, is that it will include interviews with people who have a strong vision for the future, and it involves a lot of — it involves exciting and deep collaborations with a bunch of artists who are helping me, and hopefully others, to see that, because I feel like as much as we talk about arts and sciences and everybody collaborating, it doesn’t really happen as much as we want it to. But there’s a lot of different art we could be making to help people see their way into the future.

Tippett: And there’s a lot of poetry in the book …

Johnson: Ooh, yes.

Tippett: … which I said to you I’ve been — one thing I’ve been craving these last weeks is just a little bit of poetry, here. I think a lot about what I call the generative narrative, the generative landscape of our time, which I know, as a person in media, is just not covered as well, is not investigated with as much sophistication as we have to investigate everything that’s failing and catastrophic. And I wonder if — I feel like in your work — like in this book, you introduce us to Eunice Newton Foote. There’s a whole lineage that you are in — names we don’t remember, people who’ve contributed. And I wonder, also, just —

Johnson: It was Dr. Katharine Wilkinson, coeditor of All We Can Save, who introduced me to Eunice. I feel like I’m on a first-name basis with her, even though she was doing her research in 1856, when she discovered that carbon dioxide was a greenhouse gas and would warm the planet. A woman discovered this through experimentation in her backyard and was essentially erased from history. An Irish physicist a few years later came to a very similar discovery and was credited as “the father of climate science.”

Tippett: Someone with a Y chromosome.

Johnson: And Eunice also signed the Seneca Falls Convention.

Tippett: Oh, really?

Johnson: So she was, as Katharine and I like to say, the first climate feminist — although she didn’t really see this whole apocalypse coming, per se. [laughs] She was just like, This turns out it will warm the atmosphere, if we emit all of this carbon dioxide.

Tippett: So there’s also somebody you mention, who I learned about through you — Ayisha Siddiqa — and this incredible poem, which I guess told you I’d like for you to read to us, and then we’ll open it up for questions. But just say — so to me, also, again, just the story of who this person is fills out the story that we don’t know.

Johnson: So this young woman, Ayisha, I met at the big youth climate march in New York City. I guess it must’ve been September 2019, perhaps — hundreds of thousands of people in the streets of New York, millions of people around the world. And she was one of a dozen or so young people who was leading that particular march. And I was just absolutely in awe of them. And so I came across this poem that she posted on Instagram, and just, it knocked my socks off.

Tippett: Yeah, that she wrote.

Johnson: Even just the title, which is: “On Another Panel About Climate, They Ask Me to Sell the Future and All I’ve Got Is a Love Poem.”

“What if the future is soft and revolution is so kind that there is no end to us in sight.

“Whole cities breathe and bad luck is bested by a promise to the leaves.

“To withstand your own end is difficult.

“The future frolics about, promised to no one, as is her right.

“Rage against injustice makes the voice grow harsher yet.

“If the future leaves without us, the silence that will follow will be an unspeakable nothing.

“What if we convince her to stay?

“How rare and beautiful it is that we exist.

“What if we stun existence one more time?

“When I wake up, get out of bed, my seven year old cousin

“with her ruptured belly tags along.

“Then follows my grandmother, aunts, my other cousins

and the violent shape of their drinking water.

“The earth remembers everything,

our bodies are the color of the earth and we

are nobodies.

“Been born from so many apocalypses, what’s one more?

“Love is still the only revenge. It grows each time the earth is set on fire.

“But for what it’s worth, I’d do this again.

Gamble on humanity one hundred times over

“Commit to life unto life, as the trees fall and take us with them.

“I’d follow love into extinction.”

I mean, kids these days. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] It’s true. It’s true.

Johnson: Gets me every time.

But this idea that we can be motivated by love, I think it’s just — it’s just the more delightful way to approach something that is the work of our lifetimes: to do it, thinking about not just the love of other species, but the love of other humans, the love of ecosystems, the love of places. I mean, we all have places that we’re deeply attached to, and many of them are changing for the worse. And so this potential to have that be our driving force is, to me, why I focus on solutions instead of raging against the machine. I mean, believe me, we need to stop with the oil and gas pipelines, [laughs] and I fully support people who are protesting those construction projects and taking us decades in the wrong direction, but for me, it’s all about how do we build the future that we want to live in, where there’s a place for us and the people and the things that we love?

Tippett: There’s someplace you said, “We saunter, we lollygag, we mosey away from the brink instead of running full-tilt toward a livable climate future.” And I think the context of that remark was, to run full-tilt — we run full-tilt towards what we love and what delights us.

Johnson: And towards what we can see, which, when we don’t spend enough time talking about the future we could have and engaging our imaginations and envisioning a world where we actually implement all these climate solutions we already have, then why would you run towards an abyss? If all it looks to you is just a blank canvas, then it’s sort of insane to run full-tilt toward that. And so I think, as a society, we just have a lot of work in filling in those details for each other, so it feels less scary to run towards this future.

[music: “Cradle Rock” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. We spoke at the 2022 TED Conference, and she took a few questions from the audience.

[music: “Cradle Rock” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Audience Member: I grew up in the Midwest, probably 800 miles from the nearest ocean. I don’t know that I saw the ocean until I was a teenager. But I grew up loving the ocean and the creatures in it, because of a wonderful, charismatic cultural hero by the name of Jacques Cousteau. Maybe what this moment needs is another charismatic cultural hero. Maybe it could be you.

Johnson: [laughs] That is very sweet of you to say. I think the thing that Jacques Cousteau’s own grandson, Philippe, told me was that there cannot be another Jacques Cousteau, because our media landscape has changed so much that having one leader, one charismatic person, I think is not really possible in the same way as it was before.

But I think it’s also deeply unwise to have so much dependence on one person, who could be assassinated, as we’ve seen in civil rights movements; who could burn out, as we’ve seen in environmental movements; who might just want to take a break and have a family. So I think this is a moment that calls for many leaders, because what we need is transformation in every community, in every sector of the economy, in every ecosystem, with the hundreds of climate solutions we have. So I’m deeply flattered by your question and comment, but I am so glad that there are more and more people who are doing what I’m doing and saying these similar things.

Tippett: Maybe one more. I don’t know, but I haven’t been paying attention to who had their hand up first.

Audience Member 2: I’m curious what you thought. It seems to me that a lot of the focus on environmental pieces have been the costs that we’ve thrown into societies. I was wondering what you thought about that.

Johnson: I think it’s so funny that people say it’s too expensive to solve climate change, because it’s just like, what’s your alternative? Like, if your alternative is understanding the climate projections from the world’s top scientists as basically driving humanity off a cliff, then nothing is too expensive.

But on a more specific level, when we do a cost-benefit analysis, we have to talk about the benefits. And all of these conversations about the cost of transitioning away from fossil fuels or the cost of conserving ecosystems or the cost of building things in different ways or the costs of research and development to have ever more sophisticated tools that we need — we have to talk about the immense value, much of which can be quantified and much of which is intrinsic and existence value, to use the language of environmental economics.

And I just find that so sort of absurd, that we don’t do both sides of the equation. We’re like, it’s expensive. And it’s like, compared to what? And I think — there’s a great jazz song called “Compared to What?” that always comes into my head when I hear people say how expensive it is.

Tippett: Would you like to sing it for us? [laughs]

Johnson: There’s no words, which is sort of apt.

Tippett: Well, also, the cost of failing, right? [laughs] What is the apocalyptic cost of doing nothing?

Johnson: It is infinite. And if you’re motivated purely by counting pennies and not by saving life on Earth, then we’re just not speaking the same language. [laughs]

Tippett: You do work a lot with what are new words we need, what are new images. And I talked to Colette Pichon Battle about this, too. I feel like the word “climate,” which we use as a shorthand, doesn’t quite — because you don’t “love” the climate, right? You love the world. You love the creatures. You love life.

And I just wonder if you’ve thought about that. And I do think it’s important, because we know that, also, there’s so much fear going around, and there’s so much fear that is reasonable, and it gets people living fearfully — living out of the fear place in their bodies. It’s a lot to ask of them, to take in a kind of rational analysis of a threat or just to take in the information. But do you think about how language might soften and open some of those, what feel like chasms, now?

Johnson: The word that I’ve started using more and more is “transformation,” because we’ve talked about a transition away from fossil fuels; we’ve talked about what we’re going to stop doing; we’ve talked about how we need to do other stuff. But I think the word “transformation” has embedded within it the sense of possibility: what are we going to become?

And I think that’s a really exciting question. And so words that embrace possibility, words that are not big and fancy, but are clear — like “sustainability” is basically meaningless. And someone once said to me that the term “sustainability” is just too low a bar, because we don’t actually want to sustain what we have right now. And imagine if someone — you asked someone if their marriage was — how their marriage was doing, and they said, It’s sustainable.

[laughter]

You’d be like, Are you sure you want to stay married?

Tippett: [laughs] Right. Well, also, that word presupposes that we will get to some place that will be sustainable. It’s not dynamic. And actually — I mean, and you were talking about transformation of us and of our entire understanding of the natural world —

Johnson: Of society and policy and economy and culture —

Tippett: Society and all that interrelationship — you’re talking about wholeness, really.

Johnson: Yeah. I think a lot of — it’s a very Western, white academic approach, to break things down into the smallest possible units and then try to put it all back together with algorithms and — that’s not how nature works. That’s not how humans work. That’s not how societies work. There are all these incredible emergent properties to how we live together, to how ecosystems flourish. And so thank you for that, because I think approaching these challenges with a sense of wanting to preserve wholeness and keep things intact and together — and I have this feeling that I just want to wrap my arms around as much of the world that I can, not just hugging redwood trees, but daisies and slugs and parrotfish and octopuses and all of it — and occasionally, other people. Humans are often disappointing, but some of them are really good. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] Well, I think I speak for all of us in saying that I’m really grateful now to have this experience of you, and so when I think about this, what we are up against, about this “us,” that you’re in it, and your energy and your perspective and your words and your science.

Johnson: And what if?

Tippett: And what if.

Johnson: What if we get it right?

Tippett: Thank you, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. And thank you for all being here. And thanks to TED.

Johnson: Thank you, Krista.

[applause]

[music: “Collide Us” by Signal Hill]

Tippett: Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is co-founder of the Urban Ocean Lab, a think tank for coastal cities. She’s one of the creators of the podcast How to Save a Planet, and she coedited the wonderful anthology All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. She’s also cofounder of The All We Can Save Project, and you can learn more about that at allwecansave.earth.

And special thanks this week to Keryn Gottshalk and Claire McGettrick at TED. This conversation was recorded at the 2022 TED conference in Vancouver, Canada. You can hear all of the talks coming out of that conference by finding and following the podcast TED Talks Daily.

[music: “Collide Us” by Signal Hill]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, Amy Chatelaine, Cameron Mussar, and Kayla Edwards.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation, dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.