Basil Brave Heart and Susan Cheever

Spirituality and Recovery

We explore the spiritual aspect of addiction and recovery from two illuminating perspectives. Susan Cheever has written a biography of Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson. She knows addiction in her own life and that of her father, the fiction writer John Cheever. Also, Lakota teacher and healer Basil Brave Heart of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He describes how the 12 Steps find powerful resonance in indigenous spiritual practices.

Guests

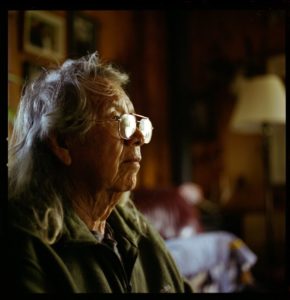

Basil Brave Heart

is a Lakota spiritual healer and author. He served in the Korean War and lives on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Susan Cheever is the author of several books, including My Name Is Bill, a biography of the co-founder of AA.

Transcript

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. In 1961 the eminent psychologist Carl Jung wrote a now-famous letter to Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, about an alcoholic he had attempted to treat in psychotherapy. Jung wrote, “His craving for alcohol was the equivalent on a low level of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, the union with God.” Alcohol in Latin is spiritus, and you can use the same word for the highest religious experience, as well as for the most depraving poison. Jung concluded, with the founders of AA, that the human spirit plays a critical role in the illness of addiction and in any possibility of recovery.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about belief, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today we’ll explore spiritual aspects of addiction and recovery.

An estimated one in 13 American adults abuses alcohol or is addicted to it. Until the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous in the 1930s, this was a ruinous and nearly always fatal affliction, immune to the best methods of psychology or medicine. AA holds anonymity as a core value, and it doesn’t track statistics on recovery, but it has saved or repaired the lives of countless millions of people across the world. It’s done so in part by analyzing addiction as a physical, mental and spiritual disease. Recovery is as much a way of life as a program. It’s a spiritual discipline that a recovering alcoholic or addict undertakes in relationship with others.

The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous is the guiding text crafted in 1939 by the movement’s first hundred or so members. Here’s a recording of AA co-founder Bill Wilson reading in 1963 from a chapter called “How It Works.”

Bill Wilson: Our stories disclose in a general way what we used to be like, what happened, and what we are like now. If you have decided you want what we have and are willing to go to any length to get it, then you are ready to take certain steps. At some of these we balked. We thought we could find an easier, softer way. But we could not. With all the earnestness at our command, we beg of you to be fearless and thorough from the very start. Some of us have tried to hold on to our old ideas, and the result was nil until we let go absolutely. Remember that we deal with alcohol — cunning, baffling, powerful. Without help, it is too much for us. But there is one who has all power. That one is God. May you find him now. Half measures availed us nothing. We stood at the turning point. We asked his protection and care with complete abandon.

Here are the steps we took, which are suggested as a program of recovery. One, we admitted we were powerless over alcohol, that our lives had become unmanageable. Two, came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. Three, made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood him.

Ms. Tippett: The other nine steps of AA call for moral self-examination, making amends for harm done to others, and ongoing prayer and meditation. It’s possible to imagine in such language a quasi-religious movement, and there was a significant Christian influence in the formative years of AA. But the movement’s power over several decades has lain in part in its remarkable ability to translate across the world’s cultures and traditions. Later in this hour, we’ll hear from Basil Brave Heart of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He reclaimed traditional Lakota spiritual practices in his recovery from alcoholism. Ms. Tippett: My first guest, the author Susan Cheever, has written widely about her own experience with alcoholism and recovery and that of her father, the late fiction writer John Cheever. She immersed herself in writing a biography of AA co-founder Bill Wilson, who died in 1971. As she tells it, he was never a conventionally religious person. He grew up in an age in which religion was a driving force in the temperance movement. Faced with the incurable and devastating problem of alcohol abuse, churches sought to banish it entirely. Indeed, Prohibition imposed a legal ban on alcohol in the United States from 1920 to 1933.

But in the same era, in the New England of Bill Wilson’s childhood, the writings of American icons like Thoreau and Emerson were subtly affecting traditional ideas about God and faith. Susan Cheever suggests that these shifts in the American religious imagination made the accessible spirituality of AA possible.

Susan Cheever: What was happening in the 1850s and ’60s, before the Civil War in New England, contributed in a very direct way to what Bill breathed in and out with the Vermont air at the turn of the century. And I think the whole sort of overturning of the idea of God as an authoritarian male figure, that the divine could exist in the song of a wood thrush or the reflections in a pond, and that it could especially — this was especially Emerson’s point — that it could exist in other human beings.

And, of course, one of the things that Bill Wilson, in his genius when it comes to spirituality, understood was that it’s a mistake to prescribe faith for another person, that you can say to another person, “You must have some kind of faith,” as Alcoholics Anonymous sort of does, but you cannot say to another person, “You must have faith in X.” It can reside wherever you see it resides as long as it’s not you.

Ms. Tippett: What does that say about the spirituality of addiction itself?

Ms. Cheever: There’s a wonderful letter. In 1961 Bill Wilson wrote a letter to Carl Jung, and Jung had treated a man who ended up being one of the original men in Alcoholics Anonymous. And this man, Roland, had often talked about Jung, and Jung writes back to Bill, and he says, “That’s right.” He says, “I despaired of treating alcoholics because I knew that they couldn’t get better unless they had some kind of religious experience.” He called it religious. And then he came out with this wonderful phrase. He said, “It has to be spiritum contra spiritus.

Ms. Tippett: He draws that semantic kinship between spirits, as in alcohol and the human spirit, but more than a semantic kinship.

Ms. Cheever: Exactly. You know, many, many people in Alcoholics Anonymous will say that alcoholism, that drinking is a low-level search for God. In other words, that the role of the spirits in the abuse of spirits is profound in its multiplicity. And I think, you know, Bill Wilson understood that very well. He was a man who had turned against religion, who had walked out of church, who did not want to be told what to do, who had walked out of church specifically because they asked him to take a temperance pledge. And he just thought it was a bunch of hooey. However, he was a man who was extremely open to ideas.

Ms. Tippett: So the identification of this as a spiritual malady was more important than prescribing a spiritual treatment?

Ms. Cheever: Exactly. He says somewhere in the writing that he’s not going to give any alcoholic any rules, that everything he writes — I think it’s in the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, which he wrote, you know, later — is just suggestions. You know, he’s just a profoundly tolerant human being. And, you know, you see it in his personal life in the way he dealt with his family, but you also see it — you know, the program of Alcoholics Anonymous is imbued with this tolerance. It reeks of it. The openness of it is so astonishing to me, and that’s why, you know, I don’t mean to be dancing around, but it’s hard to pin down what faith is in terms of what Bill Wilson laid out as the program of Alcoholics Anonymous because he was so canny about not laying it down. I mean, he really wanted to make it a moving target.

Ms. Tippett: You mention this in passing, that he did have this very dramatic experience of what I think he called God, of blazing light, right?

Ms. Cheever: Absolutely.

Ms. Tippett: And a mountaintop. And didn’t he stop drinking on that day?

Ms. Cheever: Yes. There’s no question that in his story he was a man desperate to stay away from a drink. And over this period of about 10 or 15 years he put together, one piece at a time, trial and error — mostly error — the things that helped him stay away from a drink. So he would get, for instance, that if he spoke to another alcoholic he had a better chance of not drinking. And then he would think, “Oh, now I have it,” and then he’d drink again, right?

Or he would get, as he got from Dr. Duncan Silkworth, the idea that alcoholism was a disease, that it wasn’t a willpower problem, that he was allergic to alcohol, and that was why he couldn’t drink. And he’d think, “OK, now I’ve got it,” you know? And then he’d drink again. But slowly he was getting it. And the last piece, which he got during his fourth hospitalization at Towns Hospital on Central Park West, was a direct, extremely dramatic experience of God, where Bill Wilson, just feeling helpless and, you know, hopeless, fell to his knees and cried out, “God help me.” And he had — you know, the room was suffused with light, a divine light. And he said, “So this is the God of the preachers.” I mean, for him, there’s no question that he had, like St. Paul on the road to Damascus, that he had a religious epiphany and that after that experience he never drank again. But, as I keep saying, and I hate to repeat myself, he understood that that wasn’t going to happen to everybody.

Ms. Tippett: Author Susan Cheever. She’s describing what she’s learned about the spiritual content of AA through her study of the life of its co-founder, Bill Wilson. She’s also written about her own experience of addiction. I asked how her understanding of religion and faith had been shaped by her involvement with Alcoholics Anonymous.

Ms. Cheever: It’s one thing entirely to believe in a God who controls all, and it’s another thing to believe in a God who really cares whether or not you drink that tequila shot. And it makes whatever your God is, whoever your God is, it makes it very, very personal and intimate. And I think that’s one of the amazing things that Bill was able to do. He was able to take faith with a capital F, and God with a capital G, and bring it right into people’s hearts and minds so that that faith becomes, you know, whether you’re an alcoholic or you’re addicted to food or you’re addicted to heroin, God comes between your mouth and your hand. And that’s just so amazing, because usually faith is something out there waiting for you, you know? Or, I mean, usually these things are thought of, or conventionally these things are thought of as very much outside the scope of what happens between your mouth and your hand.

Ms. Tippett: What is it about alcohol that can force people so close to this intimacy that you’re describing?

Ms. Cheever: You know what? I think it’s not just alcohol. I think it’s all addiction. There is something about addiction, you know, just thinking about my own life, it comes from fear. This is just from me. You know, this is not from any other addict. But it’s kind of fear-based. You know, there’s kind of lack of trust. I mean, I certainly can talk about it right now in terms of food. I will say I’m going to eat two soy cutlets for lunch and then round about 5:00, I think, “Huh! There’s never going to be any more food in my life. I’m going to starve to death, and the cupboard’s going to be bare, and there’s going to be nothing in the fridge, and the markets are going to be shut.” And you see this fear, you know, when people hear there’s a hurricane coming, they line up at the supermarket. You know, I think that fear is very much present in human life. But so then, instead of waiting for dinner, I have to have whatever I have to. Do you see what I’m saying?

Ms. Tippett: Yeah. Yeah.

Ms. Cheever: It’s a lack of trust. It’s an inability to just think, “You know what? It’s going to be all right.” And, like, who was that, St. Julian, who said, “All will be well?”

Ms. Tippett: Julian of Norwich. Yes.

Ms. Cheever: Yeah. “All things will be well.”

Ms. Tippett: Yes.

Ms. Cheever: It’s the opposite of that. It’s a kind of panic. It’s “There’s never going to be any more food,” “There’s never going to be another drink,” “There’s never going to be enough for me.” And in my experience, addiction comes out of that, that wanting, that hunger. And that’s very intimate. In other words, you won’t get a lot of people on the radio even copping to this stuff. And, you know, therefore, to put that into remission, or to calm it down, you have to have a faith or a system or a whatever you’re going to call it that’s very intimate as well.

Ms. Tippett: Author Susan Cheever. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, we’re exploring spirituality, addiction and recovery.

Susan Cheever is a recovering alcoholic, as was her father, the late fiction writer John Cheever. Her biography of Bill Wilson, the co-founder of AA is called My Name is Bill. A strict principle of anonymity guides AA meetings. Recovering alcoholics often share their stories of desperation and hope. And this storytelling forms a basis of healing and community. I asked Susan Cheever how she would describe the spiritual effect of some of the guiding traditions of AA, beginning with anonymity.

Ms. Cheever: Well, I think the anonymity protects, you know, makes it feel safer for an addict to seek treatment, obviously, but I think it protects the incredibly private nature of it. I mean, you know, the human heart is such a private and frightening place. But I also think that it — to me, one of the greatest — I don’t know what the word is — one of the greatest foundations of spirituality is what Bill called anonymity and, you know, what Christ called humility. And I’m sure that Buddha also had a name for it.

Ms. Tippett: Storytelling, why is that a spiritual discipline? And you are a storyteller, so I really want to hear your thoughts on it.

Ms. Cheever: I think story telling is the whole game. I mean, we understand our own lives by telling ourselves stories. You know, if I say to you, “You’re an alcoholic,” you’re going to say, “Goodbye.” If I say to you, you know, “This happened to me, and this happened to me, and this happened to me, and this happened to me, and then this happened to me,” there might be something in that list of things that happened to me where you go, “You know what? That happened to me, too.” And that’s, you know, the best way of communication that we have.

Ms. Tippett: So what’s spiritual in that? What is spiritual in this discipline?

Ms. Cheever: That’s a really good question. Well, to me, you know, the most spiritual thing anybody can do is connect with another human being. And that’s how we connect: story telling. Sometimes we’re connecting with ourselves, but I think in Alcoholics Anonymous the energy of this and the ability that we all have, the incredible eloquence that we all have about our own lives is harnessed in the service of connecting one alcoholic to another.

Ms. Tippett: And that gets at another discipline or aspect of Alcoholics Anonymous, a recovery that you can also find in all the religious traditions, just this value of community, of relationship in AA.

Ms. Cheever: Well, I think what people get in AA is for an alcoholic who has not been able to stop drinking, to be able to stop drinking is one of the most miraculous things that anybody ever sees. And it isn’t just miraculous for the alcoholic, it’s miraculous for the alcoholic’s family and everyone around them. I mean, people in Alcoholics Anonymous do have a change of heart. And it’s ultimately mysterious.

Ultimately something happens to people who go to Alcoholics Anonymous with all its lack of rules and regulations that enables them to stop drinking a day at a time. And that really, I mean, this was my first exposure to Alcoholics Anonymous was when my father went. And he didn’t want to go. He’d been to meetings. He didn’t like them, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And finally he went to rehab, and he came out a different person. When he went into rehab he was just this sour — he was ready to die. He just sat around criticizing all the time. You could just tell he was miserable. And so he made everybody else miserable. And he came out of rehab and started going to AA meetings, and he was a completely different person. He was totally engaged with the world. He suddenly wanted to learn how to work the dishwasher so that he could take care of himself. You know, he was funny, he was empathetic, he was concerned. You know, he was involved in other people’s lives. I mean, he had a change of heart that blew us all away.

To my mind, you know, there’s a countervailing force to addiction. And you see it at work in people who go into Alcoholics Anonymous and go into recovery. And, you know, maybe the brain chemistry changes. I’m sure it does. And maybe it has something to do with the power of the group. I’m sure it does. But there’s something mysterious at the heart of Alcoholics Anonymous, and whether you call it God or not, there’s something mysterious there that makes people whole again. And to my mind, that’s a pretty good argument for faith.

Ms. Tippett: Susan Cheever is the author of many books, including, My Name Is Bill: Bill Wilson, His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous.

This is Speaking of Faith, today exploring spirituality, addiction and recovery. After a short break, the riveting story and insights of Lakota teacher and healer Basil Brave Heart.

Go to our Web site at speakingoffaith.org, where you’ll find an annotated guide to today’s program. The particulars section presents images and details about all the references, history, and music you’ve just heard. This week you’ll also find a copy of Carl Jung’s 1961 letter to Bill Wilson in which he talks about the power of spirituality over alcoholism. While you’re there, learn how to purchase mp3 downloads of each week’s program and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each program as well as previews and exclusive extras. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

Ms. Tippett: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about belief, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today we’re exploring the spiritual aspects of addiction and recovery.

Over half of Americans report that one or more close relatives has a drinking problem. Native people are three times more likely to become alcoholic than the rest of the population. My next guest, Basil Brave Heart, is a Lakota teacher and healer at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He’s been in recovery for over three decades. Like nearly a third of Indian children of his generation, Basil Brave Heart was sent to a Catholic boarding school, part of a long-standing federal policy whose goal was to eradicate native culture and religion. But he later reclaimed his Lakota heritage and spiritual practice, and he now uses them to help others recover from alcoholism. After 11th grade, Basil Brave Heart dropped out of school to enter the Korean War. The year was 1951, and he was 17 years old.

Basil Brave Heart: My experience with alcohol was very limited before I went into the service. But I went into service, and I finished basic training and jump school and was assigned to a combat unit in Korea. Alcohol was a way of life. I liked what it did for me. It seemed to change the way I felt about life. It looked like I was seeing something from a different pair of eyeglasses that seemed to be very different from the pain I was carrying.

Ms. Tippett: After he left the military, Basil Brave Heart married, had seven children and became a teacher. But he continued to drink, and his drinking began to destroy every aspect of his life. Twenty years passed before he sought help, and eventually found his way to the pioneering in-patient treatment program Hazelden in central Minnesota.

Mr. Brave Heart: About the second day, which was on May 5th, I had a strange feeling something was going on, and so I isolated myself, and I didn’t want to participate with the rest of the group after that evening. And I was in a big room by myself with a large glass sliding door. So I walked towards the lake, and I was standing there, and it was towards sundown. And I looked to the west, and the sun was going down, and on the horizon was red touching the earth. And above that was black, and the sun was in between. And see, I’m going to tell you some things that I have to tell you the truth because I can’t make this up. This is my life. A voice told me, in my language, that when this red sky and this black sky would come together, that I will be relieved from this and that something will be given to me, and I will not be drinking anymore. I just had a brief sense of, you know, “Maybe I’m kind of hallucinating. Maybe I’m losing my mind.” But that didn’t stay with me too long. I switched right back to the sacredness of it, and said, “I accept that something happened.”

I went back to my room that night, and I’d laid down, and I was awakened sometime in the middle of the night with a tremendous thunderstorm. And the ceiling of my room opened up, and I saw a ring of people dancing, and I heard some drums along with the thunder and lightening. And I saw some of my ancestors who passed on, my grandparents on both sides, and other aunts and uncles.

Ms. Tippett: You can take your time.

Mr. Brave Heart: And the message that I heard from my ancestors, that they were celebrating in that place where the spirits go because I was free. I didn’t have to live the life of a drunk no more.

Next morning I woke up, I felt something very different about myself. I looked out that glass door, and there was a little bird sitting there looking at me. And I thought, “I’m going to feed this bird,” because I brought a sandwich back that night, and I wanted to feed it. I opened it, and it didn’t fly away. So I fed it. I knew then that there was something profound that was happening that I couldn’t explain.

Ms. Tippett: Lakota teacher and healer Basil Brave Heart. Like many of his generation, he had all but lost touch with native spiritual beliefs and practices that existed only in oral tradition. His recovery from alcoholism began as he reclaimed them.

Mr. Brave Heart: And even then, when I looked at the 12 Step program, it was so compatible with some of our values as Lakota. One of the things that immediately compared to some ancient teachings is that whenever you deal with some sort of energy that’s self-defeating, such as alcoholism, in our teachings, is that you honor it and to acknowledge it.

Ms. Tippett: That destructive energy?

Mr. Brave Heart: Yes. And you make it a relative. And when you do that, the energy dissipates. The only difference I saw with the treatment model that I was going through at that time was it appeared that you eradicate the disease, or that you put it in the closet and close the door. In the indigenous way is you do the opposite. You put it before you, and you honor it, and you ask it to be your teacher. So alcohol, we personify something like this. Well, I personify alcoholism, and it’s my most prolific teacher I’ve ever had. It tells me each morning who I am. So each morning I honor it some way by smudging myself. And it’s still with me. And I don’t think I would be who I am if it wasn’t for that.

The word “indigenous” really is a Greek word meaning “born within.” The knowledge and the wisdom is already there. And sometimes when we get lost, like drinking or other self-defeating behavior, it’s because we forget who we are. We’re spiritual beings trying to be humans, in the human experience. And so when we work with people who are having alcohol and drug problems, we always think about as the soul has been wounded some way. And so our first initial work with them is ceremony and ritual.

Ms. Tippett: When you talk about smudging yourself, describe that to me what that means for you.

Mr. Brave Heart: If you go to a organized church, you’ll see incensing. Smudging incense is a very ancient ritual. What it really means is the spirit within the essence of an herb like sweetgrass or sage or cedar. Our belief system is that God, or the creator, reveals his divinity within all creation. So when you honor yourself and smudge yourself, and you burn something, you’re extracting the spirit of the Great Spirit onto you, and so you’re able to get that smoke and rub yourself and purify yourself. And it’s also used to prepare for ceremony.

See, our belief is that the spirits understand the archaic and symbolic language. That’s the way we communicate, or that’s the way we evoke the spirit to speak to us, to our souls. That’s the purpose of ritual is that basic symbolic language.

Ms. Tippett: Do you think of the 12 Steps also as a form of ritual with that power you described a moment ago?

Mr. Brave Heart: Exactly.

Ms. Tippett: Can you say some more about that, about what happens in ritual, what ritual makes possible, in your understanding?

Mr. Brave Heart: Ritual, again, is a deep reverence for spirit to participate in healing. Ritual also is a container. And I use the word container as “sacred space.” When you make a sacred space, or a container, that’s ancient teaching that the spirit will come in the form, whatever form, to do the healing. I was brought up from when I was a child that spirits are in a dimension so close to us, they’re present right here. I thought everybody had that belief. And it’s not true.

Ms. Tippett: No.

Mr. Brave Heart: I was brought up with my grandparents that the spirit world is just as close as possible. It’s just a thin veneer, and we are capable to communicate with that spirit world, in particularly whenever you do a ritual or a ceremony.

Ms. Tippett: So the spirit world is very close, but there is the thin veneer, and a ritual creates an opening.

Mr. Brave Heart: Creates an opening for the spirit to come and speak to you in whatever form. People’ve always asked me — I was just asked just a couple days ago by a lady who has got cancer, and she’s experiencing some things — and she asked me, “What kind of forms do spirits make their appearance?” I says, “I can only talk about myself and my experience. Sometimes they come in the form of a light. They can come in pillars of light. They can come in the form of sparks. They can come in the form of an animal or an ancestor. But if you awaken that spirit within yourself and have that knowing that there is that spiritual world, it’s a connection that is hard to explain. It’s not an intellectual explanation to it. It’s just having the knowing that they exist.”

Ms. Tippett: Lakota teacher and healer Basil Brave Heart. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media with a program on the spirituality of addiction and recovery.

Basil Brave Heart is a leader in what he describes as a movement to combine the 12 Steps of AA with native traditions in tribal communities. The death rate of American Indians from alcoholism is over 600 percent higher than the general population. In his 30 years of recovery, Basil Brave Heart has incorporated native rituals like sweat lodges, sun dance and vision quest, and he’s found these rituals enlarged by his passage through addiction.

Ms. Tippett: When you say that you personify alcohol and you’ve taken it as a relative or a piece of your life, even a friend, maybe, member of family, and that that teaches you about yourself, can you put into words some of the things you learn about yourself through alcohol or what you learn about the spirits, the way you’re describing this, that you didn’t know before, that maybe you wouldn’t know if you hadn’t had this experience of being an alcoholic?

Mr. Brave Heart: One of the things that the alcohol has taught me, and to make it a relative so I can speak to it and listen to it, I’m able to see my shadow. And it’s that shadow which has or had the energy which I was unable to comprehend but only through ritual and ceremony, that this shadow can speak to me about some of the things who I am. I will give you an example. When I went to war…

Ms. Tippett: To the Korean War?

Mr. Brave Heart: To the Korean War, and when I came back and I used alcohol to cover up the pain that I experienced as a combat veteran, there was a particular incident that happened in an island off Korea called Geoje-do, which was a Chinese prison camp. We went in there and we did some things that only the shadow, the dark side of us that can surface to do the things that we did, and to later laugh about it and drink beer. When I came back, I had no idea, when I had all those nightmares and intrusive thoughts about this prison camp, I had no idea that that was one of the things that wounded my soul, and it was haunting me because I had dreams and nightmares about these Chinese prisoners that we killed. And it was only through a ceremony through another medicine man that he told me that he was going to leave a spirit to help me. And the spirit appeared to me two weeks later and told me to do a ritual. And I did that ritual, and after I did that ritual, those dreams about these Chinese prisoners changed. They came from the dark into the light, and it was like there was a tremendous feeling of forgiveness.

Ms. Tippett: Towards yourself?

Mr. Brave Heart: Towards myself. It’s one thing to forgive someone, but to forgive yourself you need the help from a higher power to do that. And I believe, to me, the only way you can do that is to ritualize it some way. So that’s what the shadow taught me.

Because of the influence of Christianity a lot of these ways were put aside during my early years. But it was probably after 1970, or before that, these ways began to come back very strong. So, yes, vision quest was part of my sobriety. The other thing that, you know, the vision quest and the sweat lodge is powerful is that it engages the total person. What I mean by that is all your senses are engaged in the ceremonies. The first thing you will be engaged is probably when we smudge, you probably will smell the sweetgrass or the sage or the cedar. Then you may see through your eyes whatever is being used, you know, whether it be a pipe or bringing the rocks in or water, knowing that these are sacred. So you engage your sight. And then the songs and the drum, so your hearing is engaged. And also you participate in drinking the water, which involves your taste. And then also the other sense, which is the mystical sense, which certainly I feel opens up in ritual and ceremony.

So that’s really — all these things I just described totally engages a person. And people want to know what that does for healing. I think that with all those things engaged, your body and your mind and your spirit also engaged, there’s no separation. It’s all one. And beyond that, it’s really hard to explain. But I know it works. It worked for me. And when we had a sun dance, there was seven of us who originally sun danced, they all have been sober over 25, 28 years through these ways.

Ms. Tippett: Basil Brave Heart of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He still attends to the rituals of AA, including regular meetings and work with another recovering alcoholic as a sponsor. I asked why he still needs the discipline of the 12 Steps when his own tradition includes such vivid and powerful ceremony.

Mr. Brave Heart: Sobriety and recovery depends on different levels. You can be a very spiritual person, but not be someone that follows the moral laws. That’s where you have to depend on the horizontal lessons with human beings in AA meeting who can tell you how they see you, particularly if you get a good sponsor and use that sponsor correctly. In my early sobriety, I religiously talked to my sponsor about everything because the spirits aren’t going to talk to you about all these things all the time. And sometimes they speak in riddles and symbols, and it’s hard to be interpreted. I needed that human element to listen to their struggles, their weaknesses and their strengths, and to hear their experiences and continue to try to give this program away, because I think that’s a very important part of recovery is to carry the message.

Ms. Tippett: In all the studies that you’ve done and in your work, how do you explain the prevalence of alcoholism in native communities?

Mr. Brave Heart: There has been a lot of study both physiologically, which includes, of course, our chemical makeup, the types of food that we’re able to use in our diet, the change of diet, the reservation system, causing trauma to our ability to hunt and be free and be at our sacred places to do all these ceremonies. We’re talking about a wounding of the soul, of the spirit, because of all these things that have taken place. The boarding school, being traumatized by boarding school, the put-inside-a-reservation life is trauma. A lot of people say, too, is that the land has been tremendously abused, the water, the air. All these I believe indigenous people absorb because it’s a way of life that has been taken away.

And so alcohol is, going back to how I used it, I used it because I wanted a way out of the pain. I wanted a way out of the way I felt. I wanted a way out in how people perceived me and how I allowed them to define me. And I bought it. I bought the whole thing, and I allowed my ego to define my false self, not my authentic self. I have found my authentic self, and that is who defines me now, the spiritual ways. At the same time, you know, being responsible in the community, so I can survive and teach my children.

I went back to the same place where I was fired, where I was in jail over 30 times, where I got in all this trouble, and became the superintendent of the reservation school system. And I give credit to the people of AA, the principles in AA, to my elders, to my grandparents, to the medicine men, to my family.

Ms. Tippett: Basil Brave Heart is a teacher and healer at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Earlier in this hour you heard Susan Cheever, author of the book, My Name Is Bill: Bill Wilson, His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Here’s a reading from The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous commonly called “The Promises.”

Reader: If we are painstaking about this phase of our development, we will be amazed before we are halfway through. We are going to know a new freedom and a new happiness. We will not regret the past nor wish to shut the door on it. We will comprehend the word “serenity,” and we will know peace. That feeling of uselessness and self-pity will disappear. We will lose interest in selfish things and gain interest in our fellows. Self-seeking will slip away. Fear of people and of economic insecurity will leave us. We will intuitively know how to handle situations which used to baffle us. We will suddenly realize that God is doing for us what we could not do for ourselves. Are these extravagant promises? We think not. They are being fulfilled among us, sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly. They will always materialize if we work for them.

Ms. Tippett: From The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this program. Contact us through our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. There you’ll find an annotated guide to today’s program. There’s a particulars section that presents images and details about all the references, readings and music you’ve just heard. This week you can listen to my entire, unedited conversation with Basil Brave Heart, as well as an exclusive interview with theologian James Nelson on how recovery transformed his idea of sin. Also, learn how to purchase mp3 downloads of each week’s program and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each program as well as previews and exclusive extras. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

This program was produced by Kate Moos, Mitch Hanley, Colleen Scheck, and Jody Abramson. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss. Special thanks this week to Bruce Larson, Jim Nelson, and Betty Davis-Reynolds. Audio of Bill Wilson was used with permission from the general service office of Alcoholics Anonymous, which is not responsible for the content of this program. The executive producer of Speaking of Faith is Bill Buzenberg, and I’m Krista Tippett. Next week: “Marriage, Family, and Divorce.” Please join us.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.