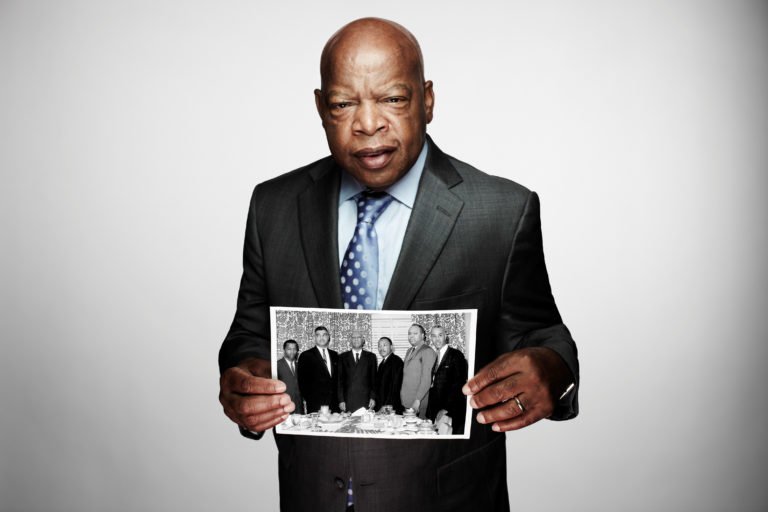

John Lewis

We Are the Beloved Community

“I discovered that you have to have this sense of faith that what you’re moving toward is already done.” Civil rights leader John Lewis on living as if the “beloved community” were already our reality.

Image by Jeremy Freeman/CNN, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

John Lewis was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia’s 5th Congressional District. He was the author of Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, Across That Bridge: Life Lessons and a Vision for Change, and March, a three-part graphic novel series. He died on July 17, 2020.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Spiritual geniuses and saints have always called humanity to love, as have social reformers who shifted the lived world on its axis. When the civil rights leaders began to force a reckoning with otherness in the 1960s, they did so in the name of love. The political, economic aspirations of this monumental work of social change in living memory grew from an aspiration to create the “beloved community.”

I did not grow up understanding this movement and its vision in this fullness, though it unfolded during my lifetime. It was brought home to me tangibly by the intensely dignified, pragmatically loving presence of John Lewis, now a congressman from Georgia, who was beaten senseless on what became known as Bloody Sunday. I was privileged to attend an annual civil rights pilgrimage with him, to holy ground in Tuscaloosa, Birmingham, Selma, Montgomery.

I’ve “remembered” so much in conversation with John Lewis and other veterans and leading lights still among us. The movement they brought into being was a spiritual confrontation in the most expansive sense of that word, first and foremost within oneself and then with the world outside. For weeks, months, before any sit-in or march or ride, they studied the Bible and Gandhi, Aristotle and Thoreau. They internalized practical, physical disciplines of courtesy and conduct — kindness, eye contact, coat and tie, dresses, no unnecessary words. They engaged in intense role-playing — “social drama” — whites putting themselves in the role of blacks being harassed, black activists putting themselves in the shoes of policemen feeling threatened and under orders to gain control.

Einstein asked a “what if” question, about pursuing a beam of light at the speed of light, on his way to comprehending the nature of light and gravity. John Lewis asked a “what if” question as a tool for social alchemy: what if the beloved community were already a reality, the true reality, and he simply had to embody it until everyone else could see?

Congressman John Lewis: When I was 11 years old, I traveled one summer with an uncle and aunt and some of my first cousins from rural Alabama to Buffalo for a visit, for a trip. I had never been outside of the South. And being there gave me hope. I wanted to believe, and I did believe, that things would get better. But later I discovered that you have to have this sense of faith that what you’re moving toward is already done. It’s already happened.

Ms. Tippett: Say some more… “And live as if?”

Congressman Lewis: And you live as if you’re already there, that you’re already in that community, part of that sense of one family, one house. If you visualize it, if you can even have faith that it’s there, for you it is already there. And during the early days of the movement, I believed that the only true and real integration for that sense of the beloved community existed within the movement itself. Because in the final analysis, we did become a circle of trust, a band of brothers and sisters. So it didn’t matter whether you were black or white. It didn’t matter whether you came from the North to the South, or whether you’re a Northerner or Southerner. We were one.

Ms. Tippett: You had made that vision real.

Congressman Lewis: For the struggle, for those of us in the struggle. But we studied. We prepared ourselves. It’s just not something that is natural. You have to be taught the way of peace, the way of love, the way of nonviolence. In the religious sense, in the moral sense, you can say that in the bosom of every human being, there is a spark of the divine. So you don’t have a right as a human to abuse that spark of the divine in your fellow human being.

From time to time, we would discuss that, if you have someone attacking you, beating you, spitting on you, you have to think of that person. Years ago that person was an innocent child, an innocent little baby. What happened? Did something go wrong? Did someone teach that person to hate, to abuse others? So you try to appeal to the goodness of every human being and you don’t give up. You never give up on anyone.

Ms. Tippett: So here’s a line from your book Across That Bridge: “The Civil Rights Movement, above all, was a work of love. Yet even 50 years later, it is rare to find anyone who would use the word ‘love’ to describe what we did.” What you just said to me illuminates that. I think part of the explanation of that is the way you are using the word ‘love’ is very rich and multilayered and also challenging — challenging for the person who loves.

Congressman Lewis: The love is there. How do you make it real? How do you paint the picture? It’s like an artist using a canvas. How do you get people to move from maybe A to B and you get C? Or from one to two and get three? You’re on a path and you have to be consistent and you have to be persistent.

Ms. Tippett: And patient.

Congressman Lewis: And patient.