Blockers

Emily VanDerWerff

Blockers tells the story of three teenage girls determined to lose their virginity on prom night; it’s also about their parents mourning the loss of their daughters, watching them grow up and learning to let them go. The 2018 movie, directed by Kay Cannon, has everything you’d expect in a sex comedy: vulgarity, ridiculous gags, and hilarious jokes. It also complicates notions of sexuality and gender in surprising ways. Emily VanDerWerff, a writer and critic-at-large for Vox, was deeply struck by the movie when she first saw it. She realized it was showing her something she never could have imagined: a life for herself as a woman.

Image by Grace J. Kim, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

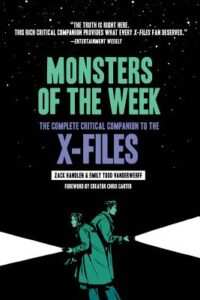

Emily VanDerWerff is the critic-at-large for Vox. Her work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Grantland, and The Baffler. She is the co-creator of the DiscoverPods-nominated fiction podcast Arden and the co-author of the book Monsters of the Week: The Complete Critical Companion to The X-Files.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, fellow movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with Emily VanDerWerff about the movie that changed her, Blockers. If you haven’t seen it, don’t worry. We’re gonna give you all the details you need to follow along.

[music: “The Breeze” by Dr. Dog]

One of my favorites things about hosting this podcast is when I get to watch a movie for the first time in preparation to talk to one of our guests, and that’s the case with this week’s episode. This movie, Blockers, has been a revelation for me. I’m kind of surprised I didn’t see it when it came out in 2018, because it’s right up my alley. I love sex comedies, and I especially love sex comedies directed by women, like Blockers, which was directed by Kay Cannon, because they take the genre to a place that you never expect.

It’s important that I say this, and I’m going to try not to repeat myself over and over again, but Blockers is a sex comedy. It has vulgarity, it has crude jokes, and it talks very openly about sexuality. It’s produced by Seth Rogen. So, if none of those things are exciting to you, this is probably not the movie for you. But if you’re willing to set all those things aside, then this movie has so much more wisdom than you would think. It’s complicated about genders, it’s complicated about love, it’s complicated about sex — and all that alongside some of the funniest jokes that you’ll see in a comedy.

[excerpt: Blockers]

Blockers tells the story of three teenage girls who want to lose their virginity on their prom night. But it’s also about their parents, their mom and their two dads, who are trying to figure out how they feel about their daughters growing up in this way.

[excerpt: Blockers]

Blockers isn’t the kind of movie that you would expect to be watching and have a revelation about yourself, all while you’re watching it, but that’s what happened to Emily VanDerWerff. She’s a writer and the critic at large for Vox. And when she saw Blockers for the first time, she realized that the movie was showing her something that she couldn’t have ever even imagined: a life for herself as a woman.

So I’d love for you to just close your eyes for a couple of seconds, and I’m gonna take you back in time to the first time that you saw that movie. So just close your eyes and think about how old you were — this was only two years ago, so hopefully this is not a difficult exercise — how old you were, where you were, and how it made you feel. And then I’ll just chime in when those ten seconds are up.

So tell me what memories came for you.

VanDerWerff: Well, first of all, as I am a lady, I will say I was in my 30s when I saw this film. [laughs]

Percy: You and I are the same age, so I’m right there with you. Go ahead. [laughs]

VanDerWerff: I went and saw this movie at a press screening, and I think it was March of 2018. I came out in late March of 2018, and it was because of a barrage of different things from different quarters that hit me at exactly the same time. And the first one of those things was Kay Cannon’s 2018 film, Blockers, which just — I was expecting to enjoy it, because I had heard from people that it was quite funny and quite good. And my wife was there with me, and we laughed a lot. I could not tell you about the plot mechanics of this movie. I could not tell you what made me laugh. I could tell you everything that the main character, played by Kathryn Newton, I could tell you about everything she wore. I could tell you about her prom dress. I could tell you about her makeup, her hair, all of that.

And what’s weird is that when you tell me to remember the movie, I am remembering a character who was not the character I saw myself in when I saw it in 2018. And that is a — it’s like a fascinating reexamination of which parts of me were attaching to what parts of that movie, which I’m sure we’ll get into in a second, but it is related to the depersonalization and the disassociation that comes with being trans.

But I saw that movie — I’m sitting in the theater, and at that time, I saw the character played by — I want to say her name is Gideon Adlon. Gideon Adlon, and she was playing a teenage lesbian — she was very funny; she was very fun.

Percy: Sam, Sam Lockwood.

VanDerWerff: I saw the character and just was like, oh, this is who you were in high school. You were this awkward, strange, teenage girl who was into girls, wanted to kiss them, didn’t know how to make that happen, didn’t know how to tell people that’s who you were, didn’t know how to just say those words.

Percy: That’s one of the really interesting things, is the only person who knows that she’s actually a lesbian is her father. And he knows it, but he wants to protect her own experience of coming out.

[excerpt: Blockers]

VanDerWerff: Yeah, I really imprinted on that. Obviously, I was in a space where I was not out to anyone, including myself. But I saw this movie, and I really was just like, Oh — this is who you might have been, if you had just…

It’s this tricky thing in my life, is that I was adopted. I was born to a woman who was not in a place to take care of a child. And she put me up for adoption, and I went through an adoption agency that was Evangelical Christian and had very specific ideas about the “right” makeup of a family, which was that there was an older boy, and there was a younger girl. And because I was assigned male at birth, because I came out and the doctor said, “It’s a boy,” I had an entirely different life than I would have had if I had been born and the doctor said, “It’s a girl.”

And that haunts me. If I had been born a cis woman, I would have had a different family. I would have had an older brother. I would have had different friends. I would have had a different life. And I can’t think about that too much, without getting really emotional. And that is really a part of why I kind of outsourced that part of myself to movies.

So I would see a movie; there would be a girl in the movie and I would imprint hard on her; and then I would just — that information would fall out of my brain. And I think part of it was, I frequently was imprinting on teenage girls in movies, because the part of myself that was me had gotten stuck in her teenage years — which is a thing I’m always loathe to talk about, because it sounds creepy; I see why people could take that out of context. But the truth of the matter is that when you are a binary trans person, and suddenly you go through puberty and puberty feels just very distracting and weird, there’s a part of your brain that just kind of shuts down. And that’s the part that would develop alongside the other girls your own age, in my case.

And I now can look back at all these memories of myself in high school and see what a stereotypical teenage girl I was, without knowing [laughs] that I was a teenage girl — I was not tapped into that part of myself. So I would see these movies, and I would imprint onto teenage girls. And there was a reason that when I was in this vulnerable state, where I was already starting to think, OK, maybe I need to actually confront the part of myself that constantly thinks about being a woman, Blockers came along and [laughs] nudged me in the right direction.

[excerpt: Blockers]

Percy: And I want to say, one of the things that’s so powerful about all of the things that you just said is that it comes in the form of a movie that’s described just as a sex comedy, and it’s dismissed because of that. There’s a lot of tropes that come with sex comedies and what we think of, with that. And I should say, for folks who listen to this podcast, who often watch the movies before we talk about them in the episodes, [laughs] this is a very vulgar movie. If you are a fan of Seth Rogen — he produced this movie — then this movie is for you; if you are not a fan of Seth Rogen, you can listen to this conversation and enjoy it and [laughs] not have to ever watch the movie, because it does feature a man chugging beer through his butthole. So just fair warning, this is the reality of that.

But one of the reasons why I love that you chose this movie to talk about is because it on the surface is all of those things, the vulgar sex comedy, but there’s so much more going on just below. And one of the things that blew my mind that I’m so curious to hear you talk about is the way in which, not just female identity and gender identity is explored, but sexuality is explored, and that it’s seen from both the male and female point of view. It’s not just women talking about sex, and, in this case, 18-year-old women talking about sex and wanting to lose their virginity as the example of becoming an adult and moving on to college and leaving high school. But it’s also parents, women and men, talking about their daughters’ virginities and what sex should be like for a woman and what sex is like for a man. And there’s just so many layers to this.

VanDerWerff: I think that the sex comedies that last, the ones that people really attach to, are not actually about sex. I think they’re about vulnerability. I think they’re about the intimacy that comes with being vulnerable. I think the reason you have a scene of John Cena chugging beer through his butt is because that is an intimate, vulnerable moment, and the comedy plays off how squeamish and how uncomfortable that makes us, because the flipside of that is a scene where Kathryn Newton’s character talks to her boyfriend and they decide to have sex, and it’s very sweet, and it’s very almost wholesome. Those are just two sides of the same coin. We laugh at one, and we go aww at the other one, but they are playing in the same emotional territory.

I’m not a huge fan of the original American Pie — I like it. But I remember loving it when I saw it in 1999, when I was kind of the same age as some of the characters in it. And I really liked its vulnerability. I think there is this thing that happens to audiences, where we remember the most obvious, biggest details in a film. So you think about something like Blockers and, for a lot of people, what they remember is John Cena chugging beer through his butt, because it was in the trailers; it’s the big laugh-out-loud moment of the film. But the thing that makes the movie work is not, to return to American Pie, Jason Biggs having sex with a pie. The thing that makes that movie work is that all of those guys are struggling to be honest and open and emotional with the girls that they fall for. And it’s the same thing with Blockers, where it’s these teenage girls working and hoping to find a way to just be themselves, and express themselves sexually, and exist within a space where female sexuality is often demonized, and just get to live their lives in a way that makes them feel fully expressed and vulnerable and able to be open, and where they assume the world will have a generosity with them that it doesn’t always have.

[excerpt: Blockers]

VanDerWerff: I think that was a big part of why the movie spoke to me, is I had always felt weird around my own sexuality. I knew it was there somewhere, but it was so disconnected from the rest of myself. It was like I had a small add-on to my house in back, [laughs] where nobody ever went, because it’s not heated and it’s frequently winter. And that was my sexuality. It was in back; we didn’t go there unless it was summer. Bad metaphor, because summer is actually a terrible time to have sex.

Percy: Now I hope you have an all-season porch [laughs] for your sexuality.

VanDerWerff: Yes, [laughs] my sexuality. Well, my sexuality is now like, we are installing heaters, because I had to figure that all out again.

Percy: Of course.

VanDerWerff: But yes, please continue.

Percy: I love that you speak of the vulnerability, because it comes in even small details. Like even that butthole chugging scene — which, I swear, will be the last time I talk about it — John Cena is holding the character of Leslie Mann, Lisa, her hand, doing it. It is a vulnerable experience. And there are all these little moments in the movie amongst the parents — so I should say that John Cena and Leslie Mann and then Ike Barinholtz play the parents of these three girls. The three of them also learn to be vulnerable with each other, and defy the stereotypes of what it means to be a dad and what it means to be a mom. And the writers of this movie, and the director, really clearly wanted us to see all these little details of vulnerability in ways that we just normally don’t see in this genre of comedy.

VanDerWerff: Yeah, and I think one of the other things that’s fascinating about Blockers is, it was sold as a movie about parents trying to stop their daughters from having sex, and there was this, oh-ho-ho, what a regressive idea in our progressive era. But the movie is specifically about subverting that trope. Yes, the parents have anxiety about their daughters having sex, but, when the time comes, they realize it’s an important part of growing to adulthood, of growing to womanhood, of becoming yourself and owning your own sexuality. And there is a beauty to that.

Percy: I agree, and for me personally, having grown up in a Latin American, immigrant, Evangelical Christian household, with a lot of sexism and stereotypes of what a woman should be, especially around virginity and sexuality, one of the things I remember my mother telling me growing up is, “Well, sex is different for women. You’re gonna be more affected, and you’re emotionally attached.” I remember I would picture that the first time I had sex, suddenly I would literally be attached by a chain to the person that I had sex with, [laughs] because it’s like, well, that’s it.

VanDerWerff: I did that, too.

Percy: It’s just such a strange thing. And then this movie, I love that both the Leslie Mann character, the mother, and the dads all talk about these really stupid stereotypes and ideas about how women interact with sex versus how men interact with sex. They talk about them, and they’re just out there on display, and it allows us to go, “That is a really stupid thing to believe.”

[excerpt: Blockers]

VanDerWerff: I’ve been thinking about this a lot in terms of trans identities. We have known about HRT, the hormone regimen that a lot of binary trans people, including myself, take to make them have the appearance more of their gender, rather than the one they were assigned at birth. And we’ve known about that for millennia, but for trans people, you kind of have to stumble across the knowledge online that there is this thing, there is this pill you can take that will make you yourself. And I was lucky enough to have the internet to be able to find it. I’ve been doing a lot of research for a writing project on trans women in the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and they just kind of had to go out with a treasure map and be like, “What am I looking for?” And a lot of them didn’t find it until they were really, really old, or they didn’t find it and they sort of went off into the space that was called, at the time, cross-dressing societies.

And a lot of those people were cis men who enjoyed, basically, wearing drag, but a lot of them turned out to be trans women, and they got sidelined into that. So the internet has been a godsend in that regard. But just imagine the idea that we could normalize trans identities. Imagine a world where you are born, and you are told, “Oh, your gender is what you make of it, and if you don’t feel particularly attached to the one that you have, you can take pills to fix that, when you are of an age where you can decide on that.”

There’s a lot of sturm und drang around trans children. But you think about, OK, a five-year-old trans girl, literally, she’s just not getting her hair cut, and she’s gonna start wearing different clothes and ask people to call her a different name. If she “grows out of it,” it will be long before she’s in any place to have done anything involving medical assistance. And even then, it’s probably gonna happen when she’s 11 or 12 and she starts taking pills to basically block male puberty, which will not affect her if she, again, “grows out of it” and decides to stop taking those pills later in adolescence so she can go through a male puberty.

But there’s this idea that we don’t know ourselves, that we have been pathologized by society at large. And society at large pathologizes everybody who’s not a cis, straight, white man. That is what society at large does. That is its whole deal. And you talk to anyone — you talk to a person of color, you talk to a woman, cis or trans, you talk to anyone who’s on the LGBTQ spectrum — and they have a story like this. They have a story about feeling ashamed of being who they are, because our society is not built to accommodate anyone but the very specific group of people who wrote the United States Constitution. [laughs]

Percy: [laughs] That is so true. That is so true.

I don’t know if this is a stretch at all, but as you were talking, I thought — one of my favorite characters in the movie is Hunter, the dad played by Ike Barinholtz, who’s the father of Sam, the woman played by Gideon Adlon, who’s a lesbian in the movie. And I can picture Hunter — let’s say that Sam’s character was trans. I could picture Hunter saying the exact same things that he says about her as a lesbian. He’s just — on the surface, he’s so obnoxious and ridiculous and this caricature of a womanizer, but then, throughout the movie, you realize he is the most, not only perceptive one out of the three parents, but the most vulnerable and kind to her. Even though his daughter isn’t publicly out as a lesbian, he’s always known and really wants to protect her right to decide when other people know and her right to have that experience in a beautiful way. And it’s one of the most tender things about the movie.

[excerpt: Blockers]

I’m just curious what the character of Sam, watching that and even watching his interaction with her, as her dad, meant for you.

VanDerWerff: I don’t have a relationship with my father anymore. I don’t want to say it’s over forever — it could change. He could change. But he has refused to acknowledge me as I am. And I feel, as far as bars go, “Call me Emily, use she/her pronouns,” is about as low as you can get. Everybody else in my life who’s not my mother or my father does that. The people who don’t, I block on Twitter.

I can’t even think about that. It’s not that it’s foreign to me — I can imagine a girl whose single dad said, “You’re trans? Cool. We’re gonna figure that out”; I have written that girl into some of my work. I can’t imagine it for myself. It feels like something too hot to touch.

I had recently been exploring the idea of telling a story about myself if I had gone through the right puberty — if I was still trans, but I had gotten on blockers and had started taking pills. And I just couldn’t do it. I couldn’t look at it. It was too painful, but it was also too unbelievable. The women I know who transition in adulthood are women who have intense trauma, often around parental relationships, because their parents often stand in the way of them.

I can’t look at that idea, the idea you just presented. I can’t look at it, even when I write it. I desperately, desperately wish it was just the norm, but I tell you what, there’s such a pathology. There’s such an idea of — honestly, I’m thinking about this in terms of the Leslie Mann character. You have these ideas about what your child is going to be. You have these ideas about what your child is going to do. You have these fantasies of the person your child is going to become. One of my best friends has a five-year-old daughter, and she is watching as her daughter very quickly becomes a different person from the one that she thought she had. And she’s cool with that. She’s a great mom. She’s rolling with it. But what a hard thing to give up on. What a hard thing to give up on, this idea you had of who your child might’ve been.

I don’t think it’s wrong to mourn that. I don’t think it’s wrong to grieve that. I think it is wrong to get stuck there.

Percy: Exactly.

VanDerWerff: I think it is wrong to insist that your version of reality is their version of reality, and I think that’s where these relationships break down. So, in conclusion, I wish that my dad had been [laughs] Ike Barinholtz, from the movie Blockers.

Percy: But I love that you said that about Leslie Mann’s character, because where she ends up in the movie is realizing that she can mourn, but she needs to let her daughter go and be herself. That’s the biggest difference there.

[excerpt: Blockers]

And actually, one of the things that’s so powerful about this world that Blockers creates — this idealized world, in a lot of ways, and as we were talking about the relationship between the parents and their kids, that was definitely not my experience as a teenager. I don’t know a lot of people who had experiences like this; it’s definitely an idealized world. It reminds me so much of what Dan Levy — did you watch Schitt’s Creek?

VanDerWerff: I knew you were gonna say Schitt’s Creek. I have seen Schitt’s Creek, yes.

Percy: Well, in a lot of interviews, when people ask him why there’s not homophobia or a lot of the phobias that trans people and LGBTQ people face in general, in the Schitt’s Creek universe, and he talks about the fact that he intentionally didn’t want to do that. It was wanting to show what was possible if that wasn’t an issue that we even had to think about. And I watched this movie, and in a similar vein, I’m like, this is the way I wish things were; I’m not entirely convinced that it is, [laughs] but it’s what I wish for all of us — that we could get past some of the hang-ups and the misogyny and these issues we have around our sexuality.

VanDerWerff: I think a lot about when I was a kid — and I’m sure you can relate to this — we had this distrust of Hollywood. We had this distrust of the liberal media or whatever. And what I’ve come to realize is that movies, especially — TV shows, to some extent, but movies especially are a powerful vehicle for moral instruction. You see a movie like Blockers, which presents a world in which parents don’t freak out too much about their daughters having sex, as long as they know their daughters are being safe and are having a positive experience…

Percy: Consensual experience.

VanDerWerff: …knowing about consent, and yes, all of these things that we increasingly are like, yes, yes, yes, we want that for our sexual encounters — if you have a movie where they’re not freaking out about it, that removes this thing that is an important element of control of teenage girls in these spaces, or people who think they’re teenage girls and will later have other realizations about that. And I really struggle with the idea of moral instruction as a primary reason to tell a story.

When you were talking about this, the thing I thought about was the Star Trek shows. Star Trek takes place in a world in which…

Percy: That’s such a good point.

VanDerWerff: …diversity is accepted, women are in positions of power, people of color are in positions of power…

Percy: Difference just is.

VanDerWerff: Difference just exists. I’ve been re-watching Deep Space Nine, which is my favorite Trek. And for some reason, I really loved the character who had been a man and then became a woman, when I was kid — I don’t know what that was all about. Obviously, it was presented in very ’90s, Trek terms, but there was a powerful metaphor there I latched onto.

But I’ve been thinking about, one of the reasons you can get away with that in a Star Trek show is because the conflict is always coming to them. It’s some alien they’ve never met before. It’s some planet they’ve never been to before. The wormhole opens up, and somebody comes through it, and so on and so forth. But you can, at the same time, build this society of people who care for each other regardless of whatever, and their differences are accepted and celebrated. And that can be beautiful, too.

So I struggle with this, because I don’t think art should exist to tell us what to do; I don’t think art should exist to tell us what’s right, morally. But I also think that we are coming out of an era in which almost all of our art — like for 40 years — all of the art that people really latched onto for 40-some years was like, we gotta see what’s gritty and realistic. We gotta undercut this. We gotta talk about the way people really are. And it suggested that people were all greedy and avaricious — and we know that’s not true, but we kind of built a world based around that. I don’t want to say The Sopranos led to the rise of Donald Trump, because I don’t think that’s true, but I think we need to examine that a little bit more thoroughly; like, how does the art we create, create the world we live in? I used to think, not at all. I increasingly am like, you know what? I came out because I saw a sex comedy at the right time. [laughs] Anything can happen.

Percy: [laughs]

[excerpt: Blockers]

My last question for you, and this is something that you’ve already gotten to persistently, throughout this conversation, but I’m just curious how you’d answer it in this way. One of the things that I love about watching movies over and over again, when they’re good, is I always feel like the more I watch them, the more I learn and grow; and I kind of grow together, alongside the movie. I’m just curious, for you, because of the fact that you saw this before you came out as a trans woman, publicly — and presumably you’ve watched it since — how you’ve grown together; how you and Blockers have continued to grow together.

VanDerWerff: I think I’ve only seen this movie one time since.

Percy: Oh, wow.

VanDerWerff: I saw it on cable at some point. I saw part of it. I didn’t see all of it; I saw part of it on cable. And I re-watched it; I was like, this is still a very charming movie. It didn’t hit me with the same weight, because I was out. I was out, I was already on hormones. I was like, this is fun. This is a fun movie. And that was all it was.

And there are certain movies, there are certain works of art you need to leave frozen when you encountered them, because they get trapped in that time. There’s this TV show, Transparent, which is about a character played by Jeffrey Tambor — boo, hiss — who comes out as a trans woman to her adult children. And I saw that in 2014, and it was immensely powerful and meaningful to me, and then I re-watched some of it in 2019, when I was out, and I was like, you know what? I don’t need this anymore. This is a thing that got me where I needed to go, and now it’s stuck where it is. And I think that’s OK.

I think the movies that change us, the TV shows that change us, the things we consume that make us the people we are — we often leave them behind. To bring this full circle, we have to leave our parents behind. You probably always love them, you probably always care about them, they probably always love you, they probably always care about you, but you have to go off and live your life. A thing can change you, a thing can shape you, and then not necessarily be a thing you need later. In some ways, because you’ve been shaped by it, because you have been changed by it, maybe you don’t need it later.

Blockers was immensely important to me when I saw it that night, in March 2018, and almost started crying at this sex comedy everybody else was laughing at because I saw so desperately the life I should have led. But now I’m leading that life. I don’t need to be reminded that it could have existed, because I’m there.

[music: “Good as Hell” by Lizzo]

Percy: Emily VanDerWerff is the critic at large for Vox. She was the first TV editor of The A.V. Club and the first culture editor of Vox. Her work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Grantland, and The Baffler.

Point Grey Pictures, DMG Entertainment, Hurwitz & Schlossberg Productions, and Good Universe produced Blockers, and the clips you heard in this episode are credited entirely to them. The songs you heard in this episode were “The Breeze” by Dr. Dog, courtesy of Park the Van Records, and “Good as Hell” by Lizzo, courtesy of Nice Life Recording Company and Atlantic Recording Corporation.

Next time on This Movie Changed Me, I’ll be talking about Selena, or Selena, if you’re a Spanish speaker. You’ve got a week to watch it before our next conversation. Bidi bidi bom bom.

The team behind This Movie Changed Me is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Tony Liu, and Kristin Lin. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota Land. And we also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Poetry Unbound, and Becoming Wise. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

I’m Lily Percy, and here’s to the self-healing, therapy, time-traveling power of movies — for our past and future selves.

[music: “Good as Hell” by Lizzo]

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections