BONUS: A Conversation with Margaret Noodin

After Margaret Noodin recited her poem, “Gimaazinibii’amoon” / “A Message to You,” for this week’s Poetry Unbound episode, she spoke with host, Pádraig Ó Tuama, about the story behind that poem as well as the Anishinaabemowin language, translation, and the importance of language preservation.

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

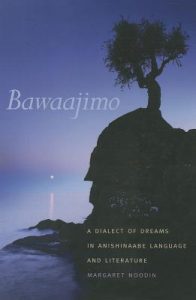

Margaret Noodin is a poet and the author of Bawaajimo: A Dialect of Dreams in Anishinaabe Language and Literature, Weweni: Poems in Anishinaabemowin and English, and What the Chickadee Knows. She teaches American Indian Literature, Celtic Literature, Indigenous Language Revitalization and Anishinaabemowin language at University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Margaret is the editor of ojibwe.net and the Papers of the Algonquian Conference.

Transcript

Margaret Noodin: “Gimaazinibii’amoon”:

“Ningikendaan akiin bakaanag

onzaam gaa nindaanikoobijiganinaanig

mazinibii’amawaawaad

onzaam wiijiwag wanishinowaad daawaad noongom

onzaam gii-izhi’iyan zhigo.

Giishkaanaabikaa ina gidaaw

gaye gichigami aawiyaan

gemaa washkiyaanimaazoyaan

gaawiin gikenimisiiyan?”

“A Message to You”:

“I know there are different worlds

because our ancestors sent them messages

because lost lovers now live in them

because you just said that right now.

Are you the carved shoreline

and I the sweet water sea

or am I the shifting wind

you cannot perceive?”

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Beautiful.

I had a couple of questions that I’d love to ask. Having listened to you, I know, Margaret, that you’re saying that the language is very verb-heavy. I was curious about, in the conjugation of the verbs, are pronouns wrapped into the verb like in Irish? I was curious about where the presence of “I” and “you” might have been, in there.

Noodin: Yes, absolutely. So the language focuses on action and relationships, and the nouns and the beings are second to that, in many ways. I often teach my students to think from the center of any action and then describe it by adding to that action word on either side. Put something in front or behind to say who was doing it or when it happened. All those things would be attached to the word so that the relationships, the connections, the time, often the place, many things are added to that action to make it more clear. So there’s instances throughout the poem when you see the short “yan” — that’s “you” — versus the “yaan” — that’s “me,” so the difference in the last two lines between saying “I” — it comes at the end of the line, or “you” — it comes at the end of the line. The English translations are never exact. I try to keep them as close as I can because I know my students and other learners read them, but you have to kind of keep to the spirit of the poem, too. So it will appear a little different in English.

Ó Tuama: I was curious, too, about the word “gichigami” and also — and I know I’m not doing the pronunciation well, but “gidaaw,” as well, these two places that seem to me to be referring to the coastline, as well as to the sweet water. Are they referring to specific places, or are they referring to the general?

Noodin: So those lines where it says “giishkaanaabikaa,” that is a word that means “carved mineral, carved edges, carved stone.” “Ina” is a question, and “gidaaw” is “you, being something.” So in that one, the syntax is almost reversed. So “giishkaanaabikaa” is a carved stone edge of something. And so in saying “giishkaanaabikaa ina gidaaw,” it’s the question, “Is this thing …?” — even that, itself, is often thought of as a sort of intransitive verb, sometimes. There are a lot of places that are described as sentient places, I guess.

And then “gichigami” is definitely the term that we use for the Great Lakes, all of the Great Lakes. They have separate names now, and there were parts and places and bays that had individual names, but you can find a lot of evidence, going back thousands of years, if you look — there is a sense that people knew this as one place. This was one watershed, one very connected set of lakes together that were central to people’s being, really. And so “gichigami” — “-gamig” is like a big sea, or a place, and “gichigami” is the largest central place for Anishinaabe Aki.

It’s interesting, because that word, “-gamig,” is what we put on the end of a — when we say “a building,” we might say mazinaa’igangamigong like the book, building, or place. So this sense of place-ness is something you could use on a water place or a land place or a building place. And gichigami is this largest central place that we have.

Ó Tuama: I’ve read that you were giving an insight into the word for translation, meaning “tying things together.” And I brought that, when I read this poem, thinking that the poem is tying the living and the dead together through voices heard and through place and through water.

Noodin: Definitely. The second line has “aanikoobijiganinaanig” — “nindaanikoobijiganinaanig” is saying “our relatives”; “aanikoobijigan” is our ancestor, which is literally “one that we’re connected to” or “tied to.” So “aanikoobidoon” is “to tie something” — literally, you might take sweetgrass and tie it to something, or you might take a rope and tie it — “aanikoobidoon.” And that word becomes a noun when we express who our ancestors — “aanikoobijigan” — one that we’re tied or connected to.

Ó Tuama: And also, you were saying that the word for peace and listening are related, which involves the quieting of the listener.

Noodin: I think that’s something we don’t teach enough in the modern world. It would’ve been a fundamental lesson, long ago. When you had oral cultures, you had a need to listen and really internalize and understand something and be able to repeat it as you heard it, but also as you understand it, and to bring it forth in a different time, in a way that is true to how it was given to you. So I think that there are connections between the way we still ourselves — be calm and quiet enough to listen — and the idea that in English we say “peace,” “peaceful,” but I think it also connects to a sense of harmony or peace between beings or places or times. Anytime you need to reverse a series of conflicts, the first, best thing to do is calm down and be quiet. I think humans have a tendency to fight back or resist things or feel that disturbance or bring it into themselves, and if they would calm down and let it go, it would be easier to get through things.Ó Tuama: I kept on recalling a story from my family, when I’ve been reading your poem and preparing for reflecting on it. About 25 years ago, my auntie went through a period of three serious bereavements in six months: her husband, her father — my granddad, and then another relative, too. And at the end of the third death, all within this space — she had six kids under the age of 21, and it was a grief upon a grief, in terms of a time for her. And she woke up in the middle of the night because her own mother, my grandmother, who had been dead a number of years, her own mother was in the room, dancing around the room in the middle of the night, holding a baby and singing to the baby. And my auntie said to her — her mother, my grandmother — she said, “Why are you dancing with a baby?” And my grandmother said, “Why wouldn’t I dance with a baby?” [laughs]

And I was thinking about the way that this poem highlights the connection, and the connection that can happen in the space of dreams, and the importance of paying serious attention to that rather than just thinking, oh, it’s just a function of the unconscious — instead saying, “This is something to be taken as a serious message” and that this is evidence of a connection that goes on beyond death.

Noodin: Absolutely. I would think that — to me, when you were telling that story, my first thought was, was she the baby? Was this a glimpse backward in her life to a moment that you might not remember, as an adult — that you were once carried as a baby, and somebody sang to you? And there might be times where you need to re-hear that, but you can’t quite remember it, as an adult. I think you’re right, there are many ways that we understand the world and the layers in it and the parallel ways, I think, of being in the world.

Ironically, this particular poem that you picked has a sense of connection to ancestors, because that’s often where I think I try to reach and move that world forward so that, for my daughters and all those who come after, we’re keeping these connections alive. But, to tell you the truth, this particular poem came out of a very real-world, modern moment of sitting in an office meeting at a workplace at a university, where someone so profoundly misunderstood what I was trying to say that I just couldn’t figure out how to express that they were completely not open to views other than their own.

And so often in the workplace, for me, the retreat mentally or spiritually, when I encounter things that attempt to erase our culture or erase language, I just have to quietly think, “Now, there’s been so much people have withstood before this. This is small. There are people we are connected to.” So this actually was a poem that came out of needing to pivot out of a sort of modern space, where the world was not hearing us or understanding our language or the need for our Native students on our campus to have certain things. They were expecting assimilation in a way that I just found so offensive, but I could not articulate to them. So the poem came as a question about whether people can understand one another and whether they can respect that we each have ancestors, and they’re really all potentially different, but that connection is something that we all have.

Ó Tuama: I had been curious about that last line, or the last two lines: “or am I the shifting wind / you cannot perceive?” And I was so struck that the poem ends — this short, eight-line poem, it ends on a note of a question, and also on a question about, is perception possible? This makes so much sense, because I had felt that the poem obviously has many cadences of consolation. But there is a deliberate change in the cadence of consolation toward the end. And that’s so enlightening.

Noodin: I think that it’s interesting you picked to look at this one now, because I live and work in Milwaukee, which is a city beset by many issues, and folks will often point to economic divide and racial divide and things happening in the United States right now. And these things have happened before. We’ve had groups of people that did not get along with one another, that had difficulty seeing and understanding one another’s ways. And I think we really have to try, on one hand, to be in a space and work through that difference, all of us, but we also have to protect ourselves and know there’s a space where you have to just shift and back up and be neutral and find a way to survive forward, without giving up who you are.

And for me, that’s something that I’m often trying to tell younger people who follow me — that you can be yourself. You can continue to do what is important to you, in a way that brings value to the world. You do not have to entirely become what others expect. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: I was curious about the title. Does the title translate directly to “a message to you”?

Noodin: It does. Well, it’s the verb. “Maazinibii” is “to write a message to someone” — “maazinibii’amoon,” so it’s literally, “I am writing a message to you.”

Ó Tuama: I was thinking about how the message to you can work in so many ways: a message to yourself, a message to the person who isn’t getting it [laughs] and seems to not want to get it, as well as a message to ancestors who can give you fortitude.

Noodin: Absolutely. I think it’s a balance. And I think that is something that, as humans, we have to remember. We have very short little lives, and things can change so much. And we’re often focused on what’s in front of us or what will happen within our lifetime. And to really send a message, either to someone who’s right in front of you that just is not seeing or hearing you in the way you wish to be seen and heard, but to be also reaching back to the connections that you have, as a person — your own ancestors, your own relatives — we often forget to build those connections and keep them alive, I think.

Ó Tuama: When I had started reading the book because I have a great love for chickadees, or coal tits, as we’d call them here, I had assumed that I’d probably land on a poem that referred to a bird. But I couldn’t get beyond this one. I mean, I read the whole thing, and I kept on coming back to this one because I was so moved by the silence and by a sense of grief within it. I was curious about, then, when I read how you speak about the chickadee — that the chickadee is one of the birds that stays all year-round, that doesn’t leave, that stays, holding onto the white pine, and continues to stay in the same place.

Noodin: I think the chickadee — for us, it’s gijigijigaaneshiinh, which is a different way of hearing that bird. You might hear, “chick-a-dee-dee-dee.” We have birdwatchers here who would teach young kids to identify the chickadee through that call. But in Anishinaabemowin, we have “giji-giji-gaane-shii-shii,” just a slightly different way of hearing that bird. And in fact, in the book, “Gijigijigaaneshiinh,” the poem for the chickadee, also plays with that idea of connection. It starts out with ““aanikoobijiganag aanikoobidoowaad”” partly because if I write something, it’s a way of teaching it, as well. So that one was a little, very short song-poem that I wrote to help remind learners that sometimes the most practical verb you have to tie things is also a way that you might speak of relatives and connections that are meaningful in other ways.

Ó Tuama: Beautiful. Whenever I hear you speaking about the connection to language and the — not just political; it is political, but it also something to do with the soul of a population who live in a place where there’s a living language, and the language is calling people to pay attention to the ensoulment of place and the language that rose up from that. And I hear you say that over and over again, when I listen to talks that you’ve given or read pieces that you’ve written, as well — talking about the fact that when you come in contact with the language that’s indigenous to the place for thousands of years, that that language itself will somehow help you to share in the soul of a place.

Noodin: Absolutely. I think it’s the best medicine. It’s the best method of getting to know a place. I think that language — obviously, as a teacher of language and a lover of language and a poet, it’s very important to me. But I think almost anyone, if you ask them, “What would it mean, if you were told not to use your language anymore?” there’s a visceral reaction to that. People understand that what you’d use, the sounds you use to express your thoughts and feelings, is so central to who you are.

Clearly, there are ways to use language — you can go a whole spectrum, good to bad, and you can say any number of things, in every language. People like to say some languages have no swear words, but every language has something that you say when you’re very angry. And I think that language really is something that can be a way to celebrate diversity.

And we’re in a time in the world where linguistic diversity — we need to think of that, because we could easily simply erase languages, and ways of thinking and connections to place, and lose them before we realize it. And they’re very, very hard to recover, as you know. We often look to the Irish as a wonderful example of having gotten a bit ahead of us, really. We strive to have our language in public schools, to have the general community, the diaspora, celebrate and use the language publicly. We’re getting closer to that point, but we’re not quite there yet.

Ó Tuama: I saw that you wrote that the word for “love” is also the word for

“opening” — “zaagi”?

Noodin: “Zaagi,” that’s one of my favorite ones to talk about. “Zaagi,” you could consider it a morpheme, just on its own, but it’s also the verb that we would use to add prefixes and suffixes and say things like “giizaagi’in,” I love you. That’s how you typically translate that. But it’s not quite the same as the English metaphor. What it refers to is all of these ways of being open, or to making outward gestures. Many of the other words that have that same sound refer to places where there’s a water outlet on the Earth, like the lakes — “zaaga’igan” or “zaaginaa,” an area where there’s a water outlet, like a bay, or where there’s a confluence. So there are ways that the idea of love and being connected are different, from one language to another. That’s why I think it’s fun for people to learn more than one.

Ó Tuama: It’s my anniversary today, actually, [laughs] so I’ve been thinking about words for love as I was texting Paul and writing him a card and stuff. And one of the ways in Irish that you can say “love” is “mo cheol thú” — “you are my music.” And it’s so interesting, the metaphors that languages reach for, and how enlivening that is.

Noodin: Yes. Now, I knew that. I taught the Irish lit. class, last semester, which I sometimes get to do. And my friend Bairbre here, who runs our Celtic Studies center, we had some comparisons in language. And we, of course, are very biased, but we felt that Ojibwe and Irish were perhaps the most musical and lovely languages that there are. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: That’s just plain fact, Margaret. That’s not bias at all. [laughs]

Noodin: I would agree. Absolutely, right? [laughs] But we wonder too, sometimes — we joke — we’ve joked for many years, within my family, and it’s not just us. So you have a confluence of history. You have people located in a similar space on the globe and really defined in ways by where the land meets the water. So, whether you are a diaspora centered around this inland sea or whether you are an island within a sea, a lot of your metaphors are similar in the fact that you’re in this northern region. You have a seasonal similarity.

But we have things like Paisake, little beings that have red hair that potentially cause disturbances or teach people lessons. And there are so many ways where, when you get to know cultures and you can make comparison between stories, you can absolutely see that the option is either to believe that they really exist and they’re all over, in every culture, in different ways, or to somehow think that people really connected sometime, long ago; but that’s probably the least likely. I think that people have a need to understand and describe the world through describing both the real and the imagined, sometimes.

Ó Tuama: And that the imagined have a real function in the process of the imagination.

Noodin: Definitely.

Ó Tuama: Just as we finish, there was one practical question that I wanted to make sure to ask, because I’ve looked around, and from what I could find, I wasn’t confident that I would’ve found the right answer, which is, in terms of ways of pronunciation of the language, I’ve heard you say “Anishinaabemowin”?

Noodin: Right. Well, so just for clarity’s sake, “Anishinaabe” is the term that you would use to describe what we also call the Three Fires Confederacy, a large diaspora of people in the Great Lakes. So, “Anishinaabe” is one way of saying that. The eastern dialect would take the “a” off and say, “Nishinaabemowin.” And if we were saying it in the slow, full, more western version, like where I come from in Minnesota, “Anishinaabemowin” would be the language, “Anishinaabemowin.” But if you were on Manitoulin Island, more in the Eastern Ontario part of our larger diaspora, people would say “Nishinaabemowin.” They would sort of drop — we call them vowel-droppers, lovingly. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Well, I’d like to hear what they call you. [laughs]

Noodin: Yeah, well, they call us slow or dramatic; overwrought. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: Well, the dialect I speak is the Munster dialect. And we’re often laughed at for how we elongate the vowel sounds. People are like, my God, you’re not singing.

Noodin: The long double vowels are so delightful. Exactly.

Ó Tuama: There you are. I know. See? Another reason why, not only are Irish and Ojibwe languages superior, but also, we particularly speak the best dialects within those. [laughs]

Noodin: I would agree. I would agree. But I can’t be telling my friends in the east that. [laughs] And it’s been interesting, too — when I first learned to write and use Anishinaabemowin more, I started out in Minnesota. And they said, “Well, when you go to Michigan, you won’t even be able to understand people.” And it turned out, in some ways, true, if I was only listening with just that western ear. After a time, though, you absolutely can understand. And elders would meet one another from different places and completely understand.

But what we find is that in teaching, it will really, really give students pause, if you mix dialects, and they like consistent spelling. So we try now, in many ways, to spell with the full western dialect spelling, and the eastern folks sometimes just don’t pronounce all of it.

Ó Tuama: What a gift. Well, it’s fantastic to talk to you. Thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it.

Noodin: Yes. Well, good to spend some time with both of you, and I really — I will look forward to one day seeing you. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: So will I.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.