BONUS: A Conversation with No‘u Revilla

While preparing for this week’s episode of Poetry Unbound, host Pádraig Ó Tuama began an email correspondence with the poet, No‘u Revilla. The exchange was so rich that Pádraig asked No‘u to join him in conversation. Together they talk about poetry, queerness and how Hawaiian language, culture, and history show up in her poetry.

Guest

No‘u Revilla (she/her) is an ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) queer poet and educator. Born and raised with the Līlīlehua rain of Waiʻehu on the island of Maui, she currently lives and loves with the Līlīlehua rain of Pālolo in the ahupuaʻa of Waikīkī on Oʻahu. She has performed and facilitated workshops throughout the pae ʻāina of Hawaiʻi as well as in Papua New Guinea, Canada, and the United Nations. She is an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa and is proud to have taught poetry at Puʻuhuluhulu University in the summer 2019 as she stood with her lāhui to protect Maunakea. A winner of the 2021 National Poetry Series, her debut poetry book will be published by Milkweed Editions in 2022.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Welcome to a bonus episode for Poetry Unbound.

As I was preparing the poem “Smoke Screen,” by No‘u Revilla, I started writing to her, initially to ask for permissions. And then she wrote back, saying, “What kind of things are you likely to say about the poem?” So, of course, I responded, and then she responded to my response, and then I responded again, and pretty soon, we were pen pals.

And our correspondence spoke about poetry and language and culture and how history shows up in complicated ways in the ordinary, everyday, as you look around. And the engagements that we had were so rich that we at On Being decided that we’d ask No‘u if she would be happy to come on for a conversation. So here is that conversation. We’ll start by hearing No‘u Revilla read her own poem, “Smoke Screen.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

No‘u Revilla: “Smoke Screen”:

“for every hard-working father who ever worked

at HC&S, especially mine

Was he a green, long sleeve

jacket & god-fearing man?

On the job, bloodshot.

Marrying metal in his heavy

gloves, bringing justice to his father,

who was also a smoking man.

No bathroom breaks, no helmets, no safe words.

He whistled sugarcane through his neck,

through his unventilated wife,

his chronic black ash daughters.

This is what a burn schedule looks like.

And if believing in god was a respiratory issue,

he was like his father.

Marrying metal to make a family.

At home he smoked before he slept,

in the corner with the door

ajar, cigarette poised like a firstborn:

well-behaved, rehearsed.

Curtains drawn, bedrooms medicated.

He was always burning into something.

Part-dark, part pupils.

For my father, the night was best alone.

When only he could see through

the world and forgive it.”

Thank you.

Ó Tuama: Thank you. It always moves me so much when I hear a poet read their own work, you know, the level of texture and meaning and the weight of emotion that they bring to a particular piece.

Revilla: Yeah, I haven’t actually — it’s interesting, I haven’t read this piece a lot, but “Smoke Screen” was actually one of the first poems of mine to be published.

Ó Tuama: Oh.

Revilla: [laughs] I know. I was still figuring myself out as a poet, and because of generous mentors, the poem continues to shapeshift, and I’m forever grateful for that. It was first published in Black Renaissance Noire, in 2016, with the help of Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, who I love. And then, with the help of Brandy Nālani McDougall, it was published a second time, in When The Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through. So I’m really grateful that this poem continues to, again, shapeshift, because it’s actually one of my — it’s one of my tender poems, when I — it’s kind of the — I don’t bring it out everywhere. I don’t talk about it everywhere. So the fact that we’re talking about it, I — yes. You just make me feel all the things. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Well, I was so moved by reading your poem, and then in the emails that we had back and forth as we were talking about permissions and the textures in your poem. So I was hoping that we’d have an opportunity to talk so that we could put this out as a bonus episode for our Poetry Unbound listeners.

No‘u Revilla: Mahalo for inviting me. As I’ve said, I’ve really enjoyed our exchanges on email and talking about language and our people and our land. So this is — this is quite a pleasure for me. Thank you.

Ó Tuama: Oh, well, thank you. I was so interested in the epigraph, in the dedication, really, of the poem. This is “for every hard-working father who ever worked at HC&S, especially mine.” You know, immediately it made me look up HC&S to figure out, what is this? What’s being referred to? Is it still there? Who is HC&S? And then, of course, I was brought into not only what that meant — Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company — but then the history of that company and the history of that industry in the last 200 years in Hawai‘i.

Revilla: Yeah. My father worked there as a welder, and my father’s a good, hard-working man. And the poem is a nod to Maui’s plantation past; well, maybe not so much a nod as a knowing glance — kind of, I’m going to honor my father in this poem, and I’ll take care of the sugar barons and white oligarchy thugs in other poems.

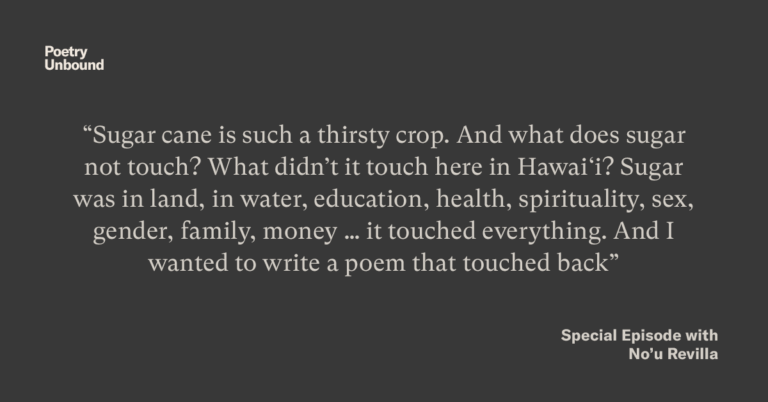

But I wanted — sugar cane is such a thirsty crop. And what does sugar not touch? What didn’t it touch here in Hawai‘i? Sugar was in land, in water, education, health, spirituality, sex, gender, family, money — sugar is very, very thirsty, and it touched everything. And I wanted to write a poem that touched back, that was tender with the complexity of working inside a machine specifically engineered to exploit Indigenous lands and people, and what it meant to do that work, to be inside that machine but still take pride in one’s ability to feed your family, put a roof over your heads, and educate your children. And that’s what my father helped do.

Ó Tuama: Yeah, there’s so much pride about his hard work and the pride he takes in his work. And at the same time, you are speaking about the conditions under which he’s working: “No bathroom breaks, no helmets, no safe words.” You hold the tension there, between a person who wants to feel like they’re doing what they can for their family, as well as somebody who’s being kind of drawn into complicity against the land, by the industry, as well as then highlighting the industry itself that was so brutal to land and to water and to everything all around it. I was reading about how fields were set on fire, and the ash and the inhalation of smoke, too, caused so much damage to whole families living nearby.

Revilla: Well, and that’s the — this poem is part of a larger book project about that time in Hawai‘i where plantations played into the sexy, affordable housing, postwar bliss, Hawai‘i’s going to go for the American dream, time in my country’s history. And you know, it’s funny when you say the ash that’s burned — we actually called that “Maui snow.” That was our snow, because we don’t have snow here in Hawai‘i, right? We don’t got snow.

Ó Tuama: We don’t have much snow in Ireland, either. [laughs] But anyway.

Revilla: But they do this, you know, they harvest the sugarcane, they burn it before you harvest it, and the ash comes down. And I’m not joking; I was a little girl, and all of us kids were so excited — oh, it’s snowing! And to take that kind of delight in something that’s literally part of destroying our land and destroying who we are and who we understand ourselves to be — you can’t know that, as a child. But that delight, that play that coexists with this brutality, this history, I like, as a poet, being in that tension and grappling with that tension. And my own father is a tender man, but he’s also a hard man, which I hope comes through in the poem. So you can’t really get away with that, as a Hawaiian today. You are in that tension. And that goes for people who have been colonized the way we’ve been.

Ó Tuama: There is a — I’m not sure that I’d have said that he comes across as a harsh man, but there’s a distance to him in the poem. There’s tenderness and pride that he has in his work, and pride that you’re showing towards him in the poem. And at the same time, you see him needing to take a break from everything. Having a smoke in the evening time is his way of retreating into himself. You get the impression that he needed to cocoon himself from everything, whether work or family, just for a period of time. There’s a sadness and a distance in the poem, too, that is — I think that’s part of the tenderness in the poem, is that the poem is honest about the distance.

Revilla: I so appreciate you, Pádraig. Thank you so much for the way you read.

Yeah, and that distance, I think, again, it can be something very heartbreaking, but it can also be, behind the scenes, “I need to be distant so that I don’t hurt you the way I’ve been hurt.” And this motif of burning in the poem — sugarcane is being burnt — he is always burning in some way. And burning can be this violence, but it can also be a way toward healing.

And I think about my father and what it took for him to do what he did, to work in that system, but he is a welder. He’s literally creating things, putting things together, performing this kind of alchemy, but under those conditions. And then he comes home, living the life he’s lived, as a Hawaiian man. And better, sometimes, keep distance from your family, especially your children, your daughters who you love, so that a certain kind of violence isn’t perpetuated on them.

Ó Tuama: You speak about him as a “god-fearing man.” And I was never sure how to weigh that. It can mean so many things, “god-fearing man.” That can be, you know, a person’s moral core, or it can be a way within which they proclaim and perform that in public, too. There was a heavy ambivalence in “god-fearing.”

Revilla: You know, the history of missionaries in Hawai‘i is heavy and violent. And missionaries were directly involved in the sugarcane industry, and they played an active role in the acquisition of land by foreigners. Missionaries and their descendants were government agents for the sugar industry. They were plantation owners themselves.

And it’s so strange, my father’s relationship to religion, my relationship to religion. I was raised Catholic, but my father never came to church with us. But my father has read the bible from front to back. And I think my father, watching him, as a child — “I’m not going to church.” But he had deliberately cultivated a relationship to God and what that meant for him as a man, as a Hawaiian man, but what that’s meant here in Hawai‘i.

And the more I learned what happened in the 19th century with missionaries, their role in the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom in 1893, their role in corporate, business elite here — it is so strange, because I have this rage and this focus on learning really what happened and educating others, but I was raised Catholic. I was raised in a Catholic church. And there’s something about ritual that — about the rituals above in Catholicism that I much enjoyed as a child. And I still, as an adult, there’s something there. So I think the “god-fearing” is definitely my father; he takes his spirituality seriously, but he also takes his moral code very seriously. But where that moral code comes from and why are questions he and I both continue to grapple with.

Ó Tuama: I was so interested, in reading around the history of the last 200 years in Hawai‘i, to read exactly what you were talking about, in terms of the absolute brutality of involvement of missionaries in the trade. I mean, on one hand it didn’t surprise me at all, because the history of Australia, of New Zealand, of Canada, of the United States, it’s a repeated motif in so many terrible ways. But there was a particular way within which the word “missionary” seemed to be so powerful and terrible in the context of that — of the history of Hawai‘i, and then the ways within which the monarchy was overthrown. [laughs] It was — am I right that a kind of a republic was set up for a few years, in between the overthrow of the monarchy and annexation?

Revilla: So-called. [laughs]

Ó Tuama: Yeah. Yeah — so-called republic. [laughs] Didn’t last long.

Revilla: Yes. And you know, what’s interesting is, I love my people. I love my people. I love my ancestors. And our language was written down by missionaries in order to proselytize us, right? Quite strategic, very smart. But we — my ancestors were so hungry. This technology of writing — “Yes, let’s take it. Let’s do it.” And Hawaiians have one of the largest, if not the largest archive of Indigenous-language newspapers, because we learned this technology, we embraced it, and we made it our own. There’s more than 10 different Hawaiian-language newspapers from the 19th century. And that’s more than 60,000 pages of articles written in the Hawaiian language.

Ó Tuama: Wow.

Revilla: And in the beginning, these newspapers written in the Hawaiian language were meant, again, to proselytize Hawaiians. But then you had Hawaiians establishing their own newspapers, talking about sovereignty, talking about the illegal overthrow, writing elegies for our chiefs and our kings and our queens and our princesses, our princes who pass. So there’s politics, there’s art, there’s spirituality being talked about. You have Hawaiians disagreeing with each other about our genealogies. It’s so — it’s so active and animated. And so — and again, it started because missionaries were trying to proselytize Hawaiians. But then look what happened. So I love that resilience, and I think that —

Ó Tuama: That’s extraordinary.

Revilla: Right? It keeps a lot of us going, when it’s just utterly hard.

Ó Tuama: You wrote an email to me that the American dream spoke English. And I’m so curious about how you wrote then about learning your own language in your 20s.

Revilla: You know, I went to Kamehameha Schools here, and I boarded, which meant I’m from Maui, but I lived on the island of Oahu, where I now live. But in high school I boarded here, on this island. And during that time, my education was excellent. It was — Kamehameha Schools is for Hawaiian students of Hawaiian ancestry. It’s an excellent education. It’s a private education.

But at the time I was going to Kamehameha, it was — it was — you were moved to go elsewhere: get this excellent education, cultivate your mind, and leave for success. And I was told — I was encouraged to learn Japanese or Spanish, as I think I told you. So I learned Spanish; I went to NYU; I double-majored in journalism and Spanish. And I love the knowledge that I gained, but I wanted to get as far away from my Hawaiian-ness — as far away as I could.

And then I found my mentor’s poetry collection — Haunani-Kay Trask, who recently passed, and my country mourned her passing. But I found her poetry collection at the Bobst Library. Like, where did that come from? I read her work, and then I read her collection of essays, and just — this is not a coincidence.

Ó Tuama: No.

Revilla: And Haunani was famous for, when she went outside of Hawai‘i and she met another Hawaiian, especially another Hawaiian woman, she’d look them in the eye and say, “You need to come home. There is a movement happening. You need to come home.”

Ó Tuama: Wow.

Revilla: And she brought me home before I even met her. And I learned my language — I am still learning my language; I am not — I’m not fluid, fluent, yet, but one of the best ways that I like learning my language continuously is reading our ‘ōlelo no’eau, which the closest thing to describe them as are proverbs, which again brings me back to psalms in the bible …

Ó Tuama: Yeah, of course.

Revilla: … just beautiful language and musical language.

Ó Tuama: Are there some proverbs that particularly stick out to you, No‘u?

Revilla: There is this one proverb. It’s — it goes — it’s very short: “I wai no‘u?” And it means — it literally means, do you have water for me? But the spirit of it is, do you have what it takes to satisfy my thirst? And this proverb can be applied to war: do you have what it takes to be my enemy? It can be applied to sex. It can be applied to a mentorship. And I can’t tell you — one of my greatest friendships started because he and I began talking about this proverb, expanding it from our kūpuna’s way of using it, and we were both like, Well, can’t it also be used for this? And can’t it also be used for that?

And we’re — you know, and that’s how language lives. That’s how cultures live, right? And I’m a water baby. I’m a water baby through and through: freshwater, saltwater, you name it, I got it — let’s go. And so “wai,” in our language, is also very — like when we ask your name, “‘O wai kou inoa?” the word for water is in our question for, who are you?

Ó Tuama: Ah. Wow. Extraordinary.

You know, I was talking to Jake Skeets, last week, and he was talking about how trade languages in themselves communicate what their primary interest is, is trade. And for him, in learning Diné, he has been so interested in learning a different economy, where trade was not the introduction of that language to his people. And I can see how colonial languages that spread around the world do that in a way of enticing people into the imagination of trade and profit.

Revilla: Well, and you know, in the 1870s, the president of the board of education, who was not Hawaiian, Charles Reed Bishop, that’s when the turn from literacy to labor began, especially for ‘Ōiwi, Native Hawaiian, youth; were trained to prepare their bodies for industrial and agricultural labor. We were trained. Like, stop reading; you’re going to get your body ready to be out in fields. And entire schools were built on that premise: these students are going to be your business elite, your lawyers, your doctors, your security forces; and these students, who happen to be the Native people of this land, will be your farmers and janitors …

Ó Tuama: Dear God.

Revilla: … and your labor. And the students — that’s when it happened, in the 19th century. “We gotta prepare their bodies to serve these people.”

Ó Tuama: And in the midst of that, there is a long tradition of literary excellence in Hawai‘i…

Revilla: Oh yes.

Ó Tuama: … which is — well, I mean, it’s not a surprise that, when something’s being taken from people, that people resist and respond by nurturing the very thing that’s being threatened. But I wonder if you could say a thing or two about that great tradition.

Revilla: Absolutely. Like what I was saying with our nūpepa, our Hawaiian-language newspapers, my ancestors — my people now love mo‘olelo, which is our word for stories, which is our word for histories and legends. And these newspapers, my ancestors wrote epics, just like any of your Greek epics, are in our Hawaiian-language newspapers. And one of my favorite things to share with students is this phrase “‘a‘ole i pau,” which means “not finished.” And “‘a‘ole i pau” was the phrase that ended — because you’re not going to — you can’t tell an epic in one newspaper article, right? [laughs]

Ó Tuama: No.

Revilla: So you had these serialized mo‘olelo across so many, so many different articles. And at the end of each: “‘A‘ole i pau.” And that was the signal, ooh, there is more to come.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Stay tuned.

Revilla: Stay tuned — exactly. Stay tuned. So can you imagine — it gives me so much joy to think about my kūpuna ferociously reading these nūpepa in their language. And these epics are just — I mean, even in English they’re beautiful. But mo‘olelo Hawai‘i — oh, these mo‘olelo are just absolutely gorgeous. I mean, the way they — we take our name so seriously. And in fact, I grew up in Wai‘ehu. And the name of Wai‘ehu is Līlīlehua. And I now live in Palolo, on the island of Oahu, but the rain here is the same name as my childhood rain. So it kind of feels like a full circle. But the way —

Ó Tuama: There’s the water again.

Revilla: There’s the water again. So the way that names are used to be playful, to be political, to show connections between generations, between different islands — I mean, it’s just — it’s gorgeous. And I’m so proud. I am so proud to be Hawaiian. And that archive is very special.

Ó Tuama: I mean, even talking to you, No‘u, I can hear poetry in the way you’re speaking and in the way you’re referencing phrase and mythology and recollection and the repository of the archive of peoples collected in those newspapers. Was poetry always of interest to you and that you kind of allowed yourself to turn to it? Or when you turned to it, did it feel new?

Revilla: If you ask my mother, she would tell you, “That one’s been writing forever.” And you know, I do have my mother to thank, because both my mother and father worked. And one of the things my mom did to make sure that our time alone was somewhat structured, she would leave us, and she would say — she’d leave a blank piece of paper, one of my favorite things, she’d leave a blank piece of paper on the table, and our task was to fill it with a story.

Ó Tuama: Lovely.

Revilla: Yeah, so — I love my mother for many reasons, chief of which is that. But I actually started as a fiction writer, if you can believe it.

Ó Tuama: Oh.

Revilla: I know. [laughs] I started as a fiction writer, because I wanted to write the great Hawaiian novel. And I was reading a lot of Joyce Carol Oates at one point, and I just wanted to just write a novel. But then I went and I enrolled in a class with a fantastic Māori writer, Robert Sullivan. And he’s an incredible Māori poet.

Ó Tuama: He is, yeah.

Revilla: He’s fantastic. And he’s such a fantastic teacher. And this is why teachers need to be treated better, just institutionally, because when they see you, and a teacher takes the time. So I came in, and we’re talking about my work, and [laughs] first, he said, “Why are you writing in Greek metaphors? Why are you using Greek references?” because I think I wrote something that was like, talking about Echo or Narcissus. I don’t know what was going on. But that’s colonization, right?

Ó Tuama: Yeah, totally.

Revilla: And so he called me on it, and I just was like, yeah, you’re right. That’s complete bullshit. And then he goes, “By the way, you are a poet. I think you need to come to terms with that, because this writing, you’re a poet. So knock it off.” [laughs]

Ó Tuama: Wow.

Revilla: And ever since then, I was like, OK, I’m going to listen. And I haven’t looked back since.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. I think the last question I was keen to ask you about was to talk to you about the role of queerness within your work. I’ve read some other of your poems and the way that, within the context of some of them, you reflect back on experience, on life, particularly on religion, through the lens of queerness and sex. And I’m so interested in how you do that.

Revilla: Yeah, that tension again, right? And I’m very lucky when — you know, but Hawaiians, like many Indigenous people, especially here in the Pacific, we — our people did not have straight/gay. We were — we have this saying in Hawaiian, “moe aku, moe mai”: “Sleep here, sleep there.” Everything is — it’s about relationships. And unfortunately, because I’m cis, I’m a cis femme woman, there was no model for that, for me. If you were gay on Maui, you were this kind of woman. But if you look like this, there’s no possible way you’re gay. You’re just going through a phase.

And then, of course, I went to New York, and I was — oh! Look, role models — that’s great. [laughs] And this can actually happen. This is great.

But when I was there, for school, my family thought it was just a phase — oh, she’s in college, she’s on the East Coast, it’s fine.

Ó Tuama: “Let’s blame New York.”

Revilla: It’s just, blame New York. [laughs] Exactly — blame New York. And then, you know, I came home, and I was very lucky to — it is very scary to come out, when you don’t know what’s about to happen with people you love. But I had a cousin that just told me, how dare you think that little of us, that we wouldn’t catch you? Like, you have to give us a chance to show up for you. Don’t take that away from us. So mostly everyone was OK, but someone very close with me did say, “At the end of the day, I’m Catholic,” and left it at that. [laughs] OK …

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Did you say, “So am I?”

Revilla: I was like, well, Jesus loves me, too. [laughs]

But …

Ó Tuama: And what are you at the start of the day? That’s what I want to know, when somebody says, “Well, at the end of the day …” you’re like, well, there’s all kinds of other parts of the day, too. [laughs]

Revilla: [laughs] What did you start out — oh my goodness, the next time I get that, I’m going to “What did you start off as?”

But I love — because I didn’t have that role model — and I have strong, strong-willed women, I have sassy women in my family. And for me to be able to be open and exuberant and vivacious in my sexuality, I hope pays it forward, because if I had that? Oh my goodness, you know? How stronger I could’ve stood in who I am, and how much earlier I could’ve done that.

Ó Tuama: Yeah, to be seen.

Revilla: To be seen and to see others and to say, I believe you. This is who you are. This is who you’re telling me you are. I believe you. And I don’t think enough — not enough mana, not enough power is invested in those three simple words: I believe you.

And I hope my poetry does that, especially for young, queer, Indigenous women who think that they have to be one thing to be Indigenous, to be a good Indigenous woman. Let’s shut that shit down. [laughs]

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: That was the conversation with No‘u Revilla. Thanks very much to her for the permissions to share that poem on our airwaves and podcast feeds. You can find our Poetry Unbound produced episode about this poem in your podcast feed. Thanks as always for listening in to these podcasts from On Being Studios.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.