BONUS: Poetry That Pays Attention with Patricia Smith

Through her poetry, Patricia Smith generously, skillfully puts language around what can be seen both in the present and deliberately looking back at oneself. We are excited to offer this conversation between Pádraig and Patricia, recorded during the 2022 Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark, New Jersey. Together, they explore how memory, persona, and a practice of curiosity inform Patricia’s work, and the ways writing a poem is like writing a piece of music.

Image by Alex Towle Photography, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

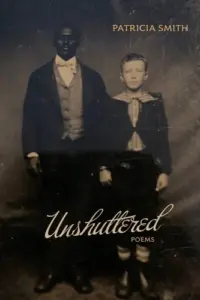

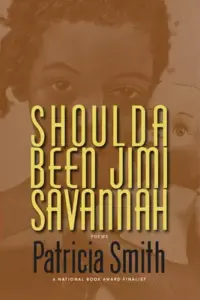

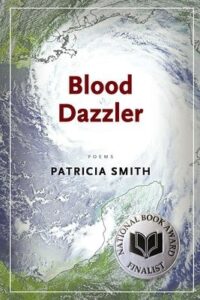

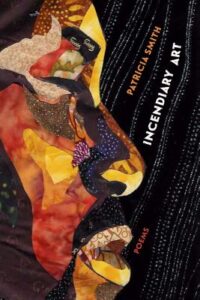

Patricia Smith is the author of nine books of poetry, including Unshuttered (Triquarterly Books, 2023); Incendiary Art (Triquarterly Books, 2017), winner of the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, the 2017 Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the 2018 NAACP Image Award, and finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize; Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah (Coffee House Press, 2012), winner of the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets; and Blood Dazzler (Coffee House Press, 2008), a National Book Award finalist. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Paris Review, The Baffler, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Tin House, and in Best American Poetry, Best American Essays, and Best American Mystery Stories. Smith is a Distinguished Professor for the City University of New York, a visiting professor in creative writing at Princeton University, and a faculty member in the Vermont College of Fine Arts postgraduate residency program.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Hi friends, thanks very much for listening to Poetry Unbound. Season seven is finished, and season eight is going to be coming out in the winter. And in the meanwhile, in between these seasons, we’re going to be releasing a few interviews that I did last year at the 2022 Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark in New Jersey in the States. It was a great time to be there. Thanks very much to Martin Farawell and everybody else involved in that festival for the invitation and the warm welcome. I know you’ll enjoy these interviews. It was a thrill to make them.

This interview is with Patricia Smith, queen of poetry on the page and the stage and everything in between. If you want to keep in touch with things Poetry Unbound you can sign up for the weekly free Substack. I write a reflection on a poem and offer a question and people respond to that every week on a Sunday. So keep in touch, and looking forward to season eight, and all the best.

Martin Farawell: Good afternoon and welcome to Poetry Unbound at the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival. We’re very lucky today to have Pádraig Ó Tuama, the host of that program, and Patricia Smith together. If you don’t know the podcast Poetry Unbound, when you leave here today you should subscribe to it. It includes some of the most thoughtful, meditative discussions, explorations of contemporary poetry that you’re going to hear anywhere. They’re really quite beautiful. Because this is being recorded for a podcast, we’re asking you to be extra careful to make sure your phones are off or silenced, on airplane mode, that if you have papers or aluminum cans or things that make noise, that you put them down, put them away, and don’t ruffle through potato chip bags or anything like that. So please help me welcome Pádraig Ó Tuama and Patricia Smith.

[applause]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: Thank you very much, Martin. And thanks to everybody involved in Dodge for the warm welcome and the opportunity for us to be here today. By way of introducing Patricia Smith, I want to quote some of your words back to you. This is from a poem called “Look At ‘Em Go” for your granddaughter, Mikaila. “I know your scars, badges / earned in the grave pursuit of science— / jump rope whips along a curve of calf, / toes stubbed purple, tender uncolored / patches of skin woven shut over your / small traumas.”

We are in the presence of somebody who makes the act of observing, the act of noticing, and the act of putting language around what can be seen, whether through persona or through the news, or through who was right in front of her, or through the poet looking back at herself, we were in the presence of somebody of the most extraordinary skill and extraordinary generosity.

Patricia Smith’s eight books include Incendiary Art, Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah, Blood Dazzler. Winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, an NAACP Image Award, a National Book Award finalist. Also, to add to all of this, because clearly you have more time, you have written children’s books, edited anthologies of essays, and mystery, and crime fiction, holding posts at City University of New York, Sierra Nevada University, and the Vermont College of Fine Arts. And in 2023, there’s a new collection, Unshuttered, about which we’ll hear in a while. Friends, it’s a joy for us to be in conversation today with Patricia Smith. And please give her a very warm welcome.

[applause]

Patricia Smith: Thank you.

Ó Tuama: I am curious, as we begin, Patricia, what was an early poem or an early poet who captured in imagination for you?

Smith: The earliest poet who captured my imagination was Smokey Robinson. And at the risk of aging myself, I used to always go to bed with that little earbud. Remember transistor radios that you would put the aerial up and I’d go to bed with that little bud. And all the stations that I listened to in Chicago would go off at night and there were some that would stay on. And I loved Motown because not only if you look at the writing itself, where they’re written in really true poetic forms, but also they told stories. It wasn’t like today where you get one line and you say it 65 times. There was a narrative arc to boy meets girl. And then the men were always begging at the end of it, which I really liked. [laughter] But Smokey Robinson — there was some really intricate rhymes in those songs. If you go back and listen to “Tears of a Clown,” things like that, it’s like, “Pagliacci? What are you talking about?” But yeah, I would say that that was the first time I noticed that stories could be told in a way that was also pleasing to the ear.

Ó Tuama: And do you think that that has continued to be a major influence on you, that early experience?

Smith: Yeah. Yeah. I’m a really musical person. My husband used to joke. He said, “We should just travel the country, go into these little towns, see if they have a jukebox, bet anyone that you could sing 90% of what comes on.” And we just travel the country that way, grifting people. Because the African American station in Chicago used to go off. I would listen to these stations out of Chicago, [WLS], WCFL, those big booming top 40 stations. So you can toss me the name of a Neil Diamond song right now and I will sing the entire thing to you. And it’s because I was always attracted to lyric and stories. I love James Taylor. I’m always listening for a way to tell a story that makes the story look new to me. And music never fails to do that.

Ó Tuama: And for you — we’ll talk about this in a while as well, but I’m curious even to hear as a beginning — for you with the absence of instrumentation and poetry, is it implied in the background, in the rhythm for you?

Smith: Yeah, I think that because I got introduced to poetry by getting up on stage and doing it, you tend to think of the voice as being an instrument. Like this poem, I am writing a piece of music. Because when you are performing and the people in the audience don’t have the poem in front of them, they can’t go home with the book, because there’s no book yet and look at it later, so you have to do whatever you can do to capture them in that moment. And if the story itself fails to capture them, you have to have done something technically with what you’re — something with forms, something with rhythm, something. So those two things were always in balance. You had to have both things so that your audience couldn’t turn away from the poem.

Ó Tuama: You’re the full band then.

Smith: Why, thank you.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] You’re welcome. I wonder, could we hear “Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah,” which is the title poem from your book?

Smith: Oh, you want to hear it, do you?

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Smith: All right. So, “Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah.” I was adult and my mother was just laughingly said, “Do you know what your father wanted to name you?” And I said, “What?” And she said, “Jimi Savannah.” And I went, “Do you know what a cool poet name that would’ve been?” And instead, she went for the incredibly industrious Patricia Ann. Anyway, that’s the story. [laughs]

“My mother scraped the name Patricia Ann from the ruins

of her discarded Delta, thinking it would offer me shield

and shelter, that leering men would skulk away at the slap

of it. Her hands on the hips of Alabama, she went for flat

and functional, then siphoned each syllable of drama,

repeatedly crushing it with her broad, practical tongue

until it sounded like an instruction to God, [and] not a name.

She wanted a child of pressed head and knocking knees,

a trip-up in the doubledutch swing, a starched pinafore

and peppermint-in-the-sour-pickle kinda child, stiff-laced

and unshakably fixed on salvation. Her Patricia Ann

would never idly throat the Lord’s name or wear one

of those thin, sparkled skirts that flirted with her knees.

She’d be a nurse or a third-grade teacher or a postal drone,

jobs requiring alarm-clock discipline and sensible shoes.

My four downbeats were music enough for a vapid life

of butcher-shop sawdust and fatback as cuisine, for Raid

spritzed into the writhing pockets of a Murphy bed.

No crinkled consonants or muted hiss would summon me.

“My daddy detested borders. One look at my mother’s

watery belly, and he insisted, as much as he could insist

with her, on the name Jimi Savannah, seeking to bless me

with the blues-bathed moniker of a ball breaker, the name

of a grown gal in a snug red [dress] and unlaced All-Stars.

He wanted to shoot muscle through whatever I was called,

arm each syllable with tiny weaponry so no one would

mistake me for anything other than a tricky whisperer

with a switchblade in my shoe. I was bound to be all legs,

a bladed debutante hooked on Lucky Strikes and sugar.

When I sent up prayers, God’s boy would giggle and consider.

“Daddy didn’t want me to be anybody’s surefire factory,

nobody’s callback or seized rhythm, so he conjured

a name so odd and hot even a boy could claim it. And yes,

he was prepared for the look my mother gave him when

he first mouthed his choice, the look that said, That’s it, [Otis]

you done lost your goddamned mind. She did that thing

she does where she grows two full inches with righteous,

and he decided to just whisper Love you, Jimi Savannah

whenever we were alone, re- and rechristening me the seed

of Otis, conjuring his own religion and naming it me.

[applause]

Thank you. Thank you.

Ó Tuama: So I’m curious about, were you wearing the sensible shoes or the ones with switchblades?

Smith: Oh, now?

Ó Tuama: No, back then and now.

Smith: Oh, back then? I was really gangly and shy and the typical only child, not very social. My mother’s way of introducing me to the world was to keep me away from it. So while all people were going out and getting hit by cars and scraping their knees and falling off their bicycles and all that, I was inside and I had no choice but to start reading. I didn’t have anything else to do. So yeah, I was very turned into myself for a long time when I was growing up.

Ó Tuama: And what turned you out of yourself?

Smith: Probably my father. My father was the frustrated Blues singer, the storyteller. He taught me that there were other ways to see the world beside what I was or what’s not learning in school. So there would be people — both my mother and father worked at a candy factory. You guys know malted milk balls? [audience responds] Oh, yeah, yeah. Okay. Well, that’s like my family legacy. My mother and father worked there all their working lives, so much so that when my mother retired for like two years, you could walk into a room and you could smell sugar on her skin. It’s weird.

So my dad was the — people who worked at the candy factory. He would tell stories about them and it would be this continuing narrative, like a little soap opera, “Guess, who’s sleeping with whose wife?” And I was like eight like, “Ooh, wow.” [laughter] But yeah, he kept that up. So I knew that there was another world somewhere and I knew that there were people whose jobs, whose lives revolved around creating worlds. And that was an amazing thing. Especially since I was in a part of town that everybody told you to stay away from. We weren’t expected to achieve or anything. And so knowing that there was something else waiting pushed me along.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. Another thing that is present throughout so much of your work is the backdrop of the culture of religious language, “unshakably fixed on salvation. Her Patricia Ann / would never idly throat the Lord’s name or wear one / of those thin, sparkled skirts that flirted with her knees.” Religion is a power…

Smith: It sounds better when he says it, doesn’t it? [laughter] I need an accent. Okay.

Ó Tuama: I can teach you the Irish accent if you like. [laughter] I think religion is a very powerful factor in the backdrop, in the culture, in the language, the vernacular of your poetry. Not proposing religion, but it’s always there as part of the conversation.

Smith: Religion has been something I’ve wrangled with for a long time because the way that my mother went about it was, “Okay, you are you, I am me. Here’s the church. We’re going to be in the church four days a week. This is what’s supposed to…”

Ó Tuama: Only four? [laughter]

Smith: “…this is what’s supposed to only what’s supposed to happen to you while you are in church. This is why we go to church.” So it was always like: you are living this life for what is beyond this life. And as far as my mother’s concerned, she never really looked at where she was. She was trying to teach me: there’s salvation down the road somewhere.

And I went to one of these hellfire Baptist churches where the choir was whipping up flame and the preacher was moonwalking across the stage. And then people were getting the Holy Ghost. I mean they were speaking in tongues. My mother, I could just see her eyes get wide I go, “Here it comes.” And she would be off dancing down the aisle and doing, you know — And then they made me think something was wrong with me because it wasn’t happening to me. And so I just thought I must be broken or something because the Lord is not entering me in the same way.

So it was very much — it was a big part of when I was growing up. And it wasn’t until I started writing poetry that I thought I have to come to some sort of agreement with religion. And so when you hear that voice comes through. It’s a reflection, it’s a part of who I am. Although I’m not a particularly religious person at this point, it’s so in my DNA that this is going to be part of your life forever. And I watch my mother now and she’s aging and stuff and I never really got to talk with her about it as an adult. But what’s happening here? I was looking over last night at the group of poets that I know and love and everything. It’s that I think each of us, we take little pieces of what we need and we build our own religions. And so I think that word and what word can do is a very big part of mine.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. I’m struck by the contrast in the way that you describe both your parents: one who has the eye to the people in the factory telling you the stories and the immediate present, and the other who has their eye to the, what’s beyond the horizon?

Smith: Yeah. Well, my mom was always the functional parent, not very emotionally giving. Just check your grades, comb your hair, take you to church. And my dad was the dreamer. My dad was like — and I was with him all the time. And so when he died, my mother and I looked at each other like, “And you would be who?” She didn’t know, she didn’t care to know — To this day, my mother, and she’s in the throes of Alzheimer’s now, but before that I would give her books. And when we were cleaning out her apartment, the books were still there, spine uncracked. So she never took the time to connect with what I was most passionate about. To this day, if the phone rang and my mother was on it, she’d say, “You know they’re hiring at the post office.” She wanted this function of, “Go five days a week. Get your benefits. Retire.” And poetry, the idea of creative writing was not something on her radar at all. It was like I was just playing with my life.

Ó Tuama: And do you think that that sense of absence actually gave you the acumen to which you had to write?

Smith: When I lost my father, and my father and I were so, so close, that I felt I was really blessed to have poetry. I don’t know how I would have survived it otherwise. And there’s always been a hollow there as far as my mother is concerned. So when my father died and my mother was still the same person she always was, I had to find community, I had to find like stories and other people. I had to talk to only children. I had to talk to Black women about their fathers. And it’s funny how when I talk about a distant mother, all of a sudden women were coming up to me and saying, “I know. I know.” And one of the things that this does, it’s like I thought I was all alone. And how dare you, especially as a Black woman, say, “If my mother and I were not related by blood, we would not be friends.” And saying that and having, you go, “Oh, every woman in here is judging,” like that, and then you say it and someone comes up and says, “I need to talk to you.”

Ó Tuama: And you know what they’re going to say? Do you?

Smith: Most of the time, yeah. That’s been a taboo for a long time, a woman does not — and not speak ill against, but not just talk about the hollow that’s there in a place where mothers should be. And so being in this community has helped me so much because you can read a poem and have — this happened many times during Dodge. Someone’s come up and said, nothing more sometimes than, “Me, too.”

Ó Tuama: Do you think that poetry has been some kind of an exploration of self-parenting as well? Especially in the absence after the death of your dad?

Smith: Yeah, I think my need to stay in poetry and to realize that every morning the slate is clean and you can fill it with story. I think that that’s my way of paying tribute to my dad. He just crafted these worlds for me and I’m going, “Where is this? What’s going on?” And he let me know that that was possible and that I didn’t have to dwell in the make-believe. That you can craft the world you want and then you can go out and find it. And when I think about my life, I think I get to be a storyteller all the time and I get to teach other people and I get to learn from some of the best people. So I’m surrounded by what I love to do and not many people can say that.

Ó Tuama: One of the things that many of your poems are praise songs to people, lifting them up. There’s a couple that I was curious about. I wonder if you could read “The Boss of Me,” which is from the same book.

Smith: Oh sure.

Ó Tuama: And “Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah,” the title poem that you read for us, that whole book is a memoir in verse, but not just a memoir of you, a memoir of migration and moving north to Chicago for your parents.

Smith: For a long time, I called it a memoir in verse. This is Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah. And it starts out with my parents coming up from the South and trying to see. Because I don’t see many books by people who were first-generation North, where their parents had all this hope for them and didn’t really know how to raise a child in the North. And then we were encountering a lot of things for the first time. And my parents were thinking I moved up from the South to escape racism, “Oh, and you came to Chicago.” Anyway, this is a poem about my fifth-grade teacher, Carol Baranowski, who was the first person who told me that I could be a writer in a school where nobody was supposed to be anything.

“The Boss of Me”

“In fifth grade I

was driven wild by you,

my teacher Copper pixie

with light shining from beneath

it Eyes giggling azure through

crinkled squint I

let you rub my hair I

let you probe the kinks I

clutched you, buried my nose

in the sting starch of your white

blouses I asked you if you thought

I was smart did you know

how much I wanted to come

home with you to roll and cry on

what had to be a bone-colored

carpet I found out where

you lived I dressed in the morning

with you in mind I spelled huge

words for you I opened the dictionary

and started with A I wanted to

impress the want out of you

I didn’t mind my skin because you

didn’t mind my skin I opened big books

and read to you and watched TV news

and learned war and weather for you

I

needed you in me enough to take

home enough to make me stop rocking

my own bed at night enough

to ignore my daddy banging on the front door

and my mama not letting him in I

prayed first to God and then to you

first to God and then to you

then to you and next to God then

just to you

Mrs. Carol

Baranowski do you even remember

the crack of surrender under your hand?

Do you remember my ankle socks

kissed with orange roses, socks turned perfectly

down and the click of the taps in my black

shiny shoes that were always pointed toward

you always walking your way always

dancing for a word from you? I looked

and looked for current that second

of flow between us but our oceans

were different yours was wide and blue

and mine

was”

[applause]

Thank you. I haven’t read that in so long. Thank you.

Ó Tuama: I love her when I read this poem. Do you think she knew that you loved her so much?

Smith: I realized, and I thought about her so often and I realized in the midst of some reading or somewhere I was where I thought I did never thought I would be. And I looked for her for so long. There were teacher societies and all kinds of stuff, and I could not find her. So I’m kind of trying to send the message to her.

Ó Tuama: I Googled her the other day.

Smith: Yeah. Yeah. She was wonderful and she just never — I was so fixated on her, because while all the other teachers were like, “You know you live on the West Side. You know you’re not going anywhere from here.” And she was like, “Write your story, girl. Just go.” And told my parents, she said, “You don’t have her go to this next school. She can go here. She can do this.” So she is hugely responsible for a lot of this.

Ó Tuama: She gave you some craft advice where you were speaking about — that she pummeled you with questions of whenever you were about to write. “What does that remind you of? What sound does that color make? How does that color taste?”

Smith: “What sound does that color make?” Yeah, that was a question of hers in fifth grade. And I was like, “Well, colors don’t have sound.” And eventually, she said, “You know red sounds different than blue.” And I, “Yeah, red sounds angry, blue sounds —” And so she was pushing me into, “Here’s your simile, here’s your metaphor. This is all you’re going to need. Run, my child.” And I did.

Ó Tuama: And there’s skill in that in terms of simile, metaphor, and the imagination and language in that. But it seems like it went much deeper into a certain sense of being, is that right?

Smith: Yeah, because where I grew up, everybody’s focus was on getting out of there. You can almost picture people looking out, because actually where I lived, you could look down a single street and see downtown Chicago in the distance. So it was like you’re always like, “What do I need to know to get there?” And one thing that Ms. Baranowski did, and one thing Gwendolyn Brooks did because she said, “No, no, no, girl. Look at where you are. Look at the voices of the preacher and the guy in the corner store and the butcher. That’s where your song is. If you go down there, you’re going to have to learn to re-sing your song. You have to learn to sing your song again. Here, it’s all around you and you’re thinking that you need to be beyond it.”

And so I think part of a lesson every poet has to learn is there’s nothing better than where you are. And there’s nothing better than where you’ve been. And there’s nothing wrong with turning around to look at it, even though you’ve paved a lot of it over and said, “Thank God, I’m past that moment. I have to look at it again.” Yeah, you do. You do. The pavement you think everything’s under is like going, “err.” And you go there and you revisit some things that are beautiful, some things that are happy, some things that are painful, but now you have the language that you need to confront them.

Ó Tuama: There’s a Scottish poet, Don Patterson, who says that “a poem is … a little machine for remembering itself.” And it strikes me that you’re talking about something very similar, the necessity of remembering. Not just for the point of view of a piece of art, but actually you need to.

Smith: Memory is not always pleasant. One of the things I think we’re blessed with as poets is that we have the ability to address and access things that we never wanted to look at again. Like I said, my mother is — she’s in a nursing home and she has Alzheimer’s. Right before she slipped past where I could reach her, she was talking about being buried, and I was listening very closely and she was saying, “Well, I want this kind of casket, and I want this. And I want this person to sit in the front row, and I want —” and then I realized, I said, “That’s not going to happen.” And I thought, “You’re going to be cremated.” And so dealing with that and where love is supposed to be in that, and I can’t be thrown back into the life of your church and people who don’t know me and your status in church and all that. I said, “I want to say goodbye to you personally. I think there’s some friends of yours.”

And then thinking, I need to look at that carefully. I need to say, “What’s behind this decision? Why am I not going all out and doing all these things and having this big sendoff and all that?” And that was a hard thing. I have probably about four poems about that. And just because the poems come, that does not mean you’re ready to vocalize them right away because you can feel judgment. It’s just like, “Did you hear what she said about her mother?” It happens. It happens. And so I’m trying to rectify that. I know that’s something that’s coming. There are other things, family, as you get older and you realize you’re up at the top of the list now thinking about your own dying, your aging, things like that. And so I just feel lucky that there’s some way that I can discuss those things with myself.

Ó Tuama: That’s the first audience, I suppose, is to discuss it with yourself. And if you can contain that, well then something might be containable. You said just now that memory doesn’t have to be pleasant. And I’m struck by how that is a true line in some of your works. When I think of the book Blood Dazzler, which pays such attention to what does it mean to, in persona poems, imagine what poetry that addresses the catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina and the systemic inadequacy of everything that happened regarding the response to that. That is not pleasant. Those are not pleasant poems, but they’re powerful.

Smith: Well, what we are as poets or what we should be are witnesses. And you can’t put blinders on and just say, “I’m only going to witness some things and not others.” And there’s a whole other question that always comes up about what we are allowed to witness of others. I’ve heard it come up dozens of times in conversations here about where’s the line? Where’s the exploitation? How can you write other people’s lives? How can do things like that? So that’s a whole other thing.

But in terms of Hurricane Katrina, everybody saw it. I didn’t really ever think of it as a regional tragedy. I thought of it as a human tragedy. And it let us see just what our country was capable of. There’s a lot of things that — Growing up in Chicago, there used to be a rumor that there were these huge housing projects in Chicago, and if you looked at them from the sky, they were all kind of in one place and they were easy to see. And the rumor was that, that the reason they funneled all the people from the South into the same neighborhood is because if the Black folks started to act up, you could take them out from the sky. Now ask me if I believe that, okay? And so when you’re talking about Katrina and the levies and was that purposeful and all that, I can tell some of you guys, you would be surprised what’s going on behind the scenes.

Ó Tuama: City planning is its own form.

Smith: Yeah, city planning is — So I’ve always thought about that. And so when Katrina happened, it was like the same kind of tragedy. People were like, “I’m tired of seeing Black women being lifted up in baskets. I’m tired of hearing them. Let’s get that French Quarter back together, shall we?” And we just wanted things to be palatable as soon as possible so we don’t have to dwell in anyone else’s loss. And I think that’s an issue we have with so many different things. But then I think something happened after that. I think it was Haiti, and someone said, “What, are you going to write about Haiti?” No. It’s like, “Oh, I’m just a disaster poet now.” I write about what reaches me and for a reason. And I was talking about this at my craft talk. I heard Kwame Dawes talking about a little bit today. It’s like your personal investment in the stories of others, you can’t separate yourself from that investment.

Ó Tuama: I wonder if you could read a few from Blood Dazzler and “Man on The TV Say” and then just a couple of more, too.

Smith: Sure. Everybody okay out there? [applause, cheering] You good? Thank you. Okay. This is from Blood Dazzler.

“Man on The TV Say

“Go. He say it simple, gray eyes straight on and watered,

he say it in that machine throat they got.

On the wall behind him, there’s a moving picture

of the sky dripping something worse than rain.

Go, he say. Pick up y’all black asses and run.

Leave your house with its splinters and pocked roof,

leave the pork chops drifting in grease and onion,

leave the whining dog, your one good watch,

that purple church hat, the mirrors.

Go. Uh-huh. Like our bodies got wheels and gas,

like at the end of that running there’s an open door

with dry and song inside. He act like [we’re] supposed

to wrap ourselves in picture frames, shadow boxes,

and bathroom rugs, then walk the freeway, racing

the water. Get on out. Can’t he see that our bodies

are just our bodies, tied to what we know?

Go. So we’ll go. Cause the man say it strong now,

mad like God pointing the way outta Paradise.

Even he got to know our favorite ritual is root,

and that none of us done ever known a horizon,

especially one that cools our dumb running,

whispering urge and constant: This way. Over here.”

[applause]

Thank you.

Ó Tuama: There’s a chilling nature of that poem in the sense of how hollow the advice is, given the lack of provision.

Smith: No cars, no way, but urgent. Really urgent. “You have got to go.” And if someone doesn’t come get me, I can’t move. And just also years after Katrina, I know that some students who went down to help with rebuilding. And there were still some people who were living with their houses powered by generators outside their house. But the lights in the French Quarter were on and bright.

Ó Tuama: Whenever you speak about poetry of witness and public poetry that pays attention, you also combine that with craft. And I’m struck in this about the use of tiny end-stop lines like, “Go.” Full stop. Period. And you diversify the length of line from longer ones to just ones that are like a bullet. Could you talk about that and what that does to the music? And I almost feel — I feel frightened when I hear this poem. There’s fear in me. And some of that is down to the music of stop and then longer and stop and longer that you achieve.

Smith: Coming from spoken word and adjusting my lines for effect when I know people don’t have the poem in front of them. And also realizing that that nice flowing poetic line is nice, but mostly people don’t talk like that. And doing things for emphasis and listening to how I read the poem and really wanting you at home when you pick up the book to read it the same way. Poets don’t often realize how much power they have to get the reader to read the poem exactly the way you want them to. Anything from how crowded it looks on the page, the lines you put between, where the lines breaks are.

If you want somebody to be breathless at the end of a poem, you have all the lines together with very little punctuation. If you’re writing beautifully and you want them to muse on the lines, you do couplets and you give them air and say, “Oh, that was — Let me go to the next one.” And with this, I wanted it very much to feel like real talk. I mean, sometimes we watch the news and we say, “What? How? What?” And everything’s so urgent and on edge, “Breaking news. This, that, and the other.” So when I talk about a poet’s toolbox, not only do I think it’s essential for every poet to learn form and prosody, I also think that we need to know how powerful rhythm is, how powerful speech is when we listen to it, and how best to use rhythm to replicate that speech.

Ó Tuama: Another poem where you do that is to a persona poem in this same book, “8 A.M., Sunday, August 28, 2005,” a persona poem written in the voice…

Smith: Katrina?

Ó Tuama: … of Katrina. Could you talk a little bit about what persona poem is for you? And then read the poem.

Smith: Okay. Like I said I’m originally from Chicago, and so that was the home of the Poetry Slam, like a mecca of performance poems for a long time. And when I discovered it, there were people already doing persona. That was a thing. That was like get up on stage in a poetry slam and do persona. And there was a woman there, her name was Lisa Buscani, and she did a poem in the voice of the man who cuts the hair of people before they go into the gas chamber. And that taught me so much. It taught me that sometimes the most powerful poem is on the periphery. Who would think of the barber? Most people would say, “I’m going to write a poem against the Holocaust.” And you’re always stronger when you’re person to person instead of person to event or person to concept.

So at that point, I thought I had never — And when she finished, there was this white-hot moment of silence in the room. People didn’t know what to do. And I had never seen anybody control a room that way. And I said she moved herself out of the way and had people listening directly to this barber. And the first time I started writing persona, everything was persona. I’m going to be a gym shoe. I’m going to be, you know — And it’s like anything else. When you first learn a form or something, you just write everything for a long time in that form until you figure out, “Well, what can I take from this to fold into my own voice?” And so in that toolbox, with form and all that is persona and knowing exactly when to utilize it.

And when I started that book on — I didn’t start a book on Katrina. I started writing poems and it became a book, much later, a weird series of events. And I thought, “What’s going to pull this together?” And it wasn’t pulled together. It didn’t feel cohesive to me until I personified Katrina. And even in poems where she was not, you could see her hovering and watching everything. So when the 34 nursing home residents were lost and they prayed and the next poem is, “They were praying to God? They should have been praying to me.” So it’s like she’s remorseful, she’s angry. So knowing when to get the most mileage out of her persona is part of, “I’m going to learn that and put it in my toolbox.” It’s not all the time, but when it works, it works really well.

Ó Tuama: And I mean it’s a certain form of artistic empathy with an idea or with a caricature or with a person. What do you think that speaks to the human condition? Do you think that that’s something that, whether or not you’re a poet or a writer, do you think having that faculty of imagination can help you live a life in general? Or do you think of it as a tool for the arts?

Smith: It reminds me of another discussion that I’ve heard here about — A woman came up to me actually and said, “I’m a white female writer. Do I have the right to write about Black events or Black people, things like that?” And it’s amazing how tentative we are about things like that, but then we’re constantly saying, “We don’t talk enough to each other.” The world is the way it is because we don’t understand each other. And that’s another huge thing.

But I do think that, even if I don’t write anything, I think that poetry has given me a lot of insight into at least being curious about other people’s lives. People who have nothing to do with me. I might never encounter that person again, but oh my God, what do you do? What drove you there? And looking and seeing — Somebody who is a greeter at Walmart or somebody who — there’s a guy, one of the places I teach is on Staten Island, and there’s a bus that goes back and forth between the ferry and school and the guy never says anything. And I told one of my students, I said, “Interview that guy.” And they talked to that guy and he knows everybody’s business because they’re the same people get on the bus every day. They don’t see him. They sit right behind him and talk about everything. And he recognizes them and say, “Oh, you are the one whose boyfriend is doing… ” And I said, “Nobody’s invisible. Nobody should be invisible.”

I’ve seen people here, no, not pointing anybody, but the people who you think are service people. I’ve seen her just walk all over people. The people who are here every day serving us and pointing us in the right direction and doing that. And stop one time, stop, fully stop. Don’t just talk to them while you’re still walking. Stop and ask them how they’re doing. And you’d be amazed. You’d be amazed. I think one thing poetry does is like, how are you living your life? No judgment on the life. Just how are you living your life?

Ó Tuama: Asking. Yeah. Could we hear that poem in the voice of Katrina, “8 A.M., Sunday, August 28?”

Smith: Sure. Okay. So this is going to have a weird sound to it because one of the things that happened with Blood Dazzler is it was adapted and we were an off-Broadway theater. It was a dance theater production. And so there’s a woman who took a leave from dancing in Wicked on Broadway to dance Katrina for no money. And I see her when I do this. She was fantastic.

“8 A.M., SUNDAY, AUGUST 28, 2005

Katrina becomes a Category 5 storm, the highest possible rating.

“For days, I’ve been offered blunt slivers

of larger promises—even flesh,

my sweet recurring dream,

has been tantalizingly dangled before me.

I have crammed my mouth with buildings,

brushed aside skimpy altars,

snapped shut windows to bright shatter

with my fingers. And I’ve warned them, soft:

You must not know my name.

“Could there be other weather,

other divas stalking the cringing country

with insistent eye?

Could there be other rain,

laced with the slick flick of electric

and my own pissed boom? Or could this be

“it, finally,

my praise day,

all my fists at once?

“Now officially a bitch, I’m confounded by words—

all I’ve ever been is starving, fluid, and noise.

So I huff a huge sulk, thrust out my chest,

open wide my solo swallowing eye.

“You must not know

“Scarlet glare fixed on the trembling crescent,

I fly.”

[applause]

Thank you.

Ó Tuama: We’ve never met each other apart from a couple of emails and meeting a few times this week.

Smith: I swear.

[laughter]

Ó Tuama: I swear. I’ve worked in conflict resolution for a long time. And one of the things in conflict that you know is that people who have been subject to conflict and subject to systemic conflict as well, I’m thinking in the north of Ireland particularly, where the whole system conspires to tell people that they shouldn’t believe themself about how bad things were. And one of the things that always strikes me in these persona poems of this voice of a hurricane that says, “Now officially a bitch,” and announces itself to unleash itself, is that there is a way of saying, “Your trauma is believable.” To speak back, especially in a situation that wanted to move on quickly and say, “No, the French Quarter’s back on, so, therefore, we’re moving.”

Smith: Yeah. Well, that comes personally, too. Each one of us, we know people who would, like us, to just move along, move out of this space, move along with your life, don’t waste your time on things. So I think even in a poem like that, you have to really — I think those of us who write poetry in other genres, we’re constantly having to remind ourself where we are rooted and check that root and make sure that it’s firm. So no matter where you are, that’s a pressure that doesn’t stop. “Move, you are inconveniencing me. Move, you are between me in a place I need to go. Move, you don’t belong here. You didn’t have the right education. You didn’t have the right this, you didn’t have the right that. Aren’t you from the west side of Chicago? Aren’t you a slam poet?” And so I think one of the things poetry does is reminds you again and again, “As long as I have my voice, I have myself.”

Ó Tuama: Yeah. Did it take you a long time to believe that for yourself?

Smith: Yeah, and it waivers. You walk into some spaces and you feel like you’re starting all over again. And you have to remind yourself. Did I ever think that I was going to be in a room when I met Terrance Hayes 30 years ago? If I was going to be sitting next to him talking to him last night, like old friends? I never, never thought. And there were times when I walked into a room and Terrance and other poets, Ellen Bass, Carolyn Forché, are you kidding me? That I had to say, “Okay, Patricia, it’s okay. You belong here. You’ve done something or you wouldn’t be here.” [applause] Thank you, guys. Thank you. It waivers. You never know when you’re going to come into a place and just feel, “Oh, no, it’s happening again.” And you have to remind yourself of where your strength comes from.

Ó Tuama: I’d like to talk about your project that’s coming out next year. And so I wonder if you could explain a little bit of it, and we’re going to show — You’re gonna hear a few of the poem. This is very exciting. And show some photos, too.

Smith: For years, I’m a big tag sale, estate sale person. When I met my husband, he was into old jewelry. We’d go find old jewelry, he’d resell it. But then we started collecting photographs, 19th-century photographs, cabinet cards, CDVs, daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes. We did for a long time. And then I started collecting specifically African Americans. At that time, not many African Americans could afford to have their pictures taken. Many times it was because they worked in the house of someone who was cataloging their staff, or there were people who were succeeding and were able to have pictures. So sometimes I would find whole albums. And at first, I thought it would be great, you see a name sometime, and you’d see a photographer in a studio in the city, and I would try to find descendants of the people to give them the photos back. Especially when there was a whole album. You go, “I know somebody somewhere wants this.” And it’s a thankless thing. Most times you can’t get it done. I think I’ve only done it once in all the years we’ve been collecting.

And so I started using them in workshops. At the beginning of the workshop, I would give somebody a photo and say, “All the poems you write this week are, again, tell me who this person is.” And then I would start looking at them and I’d think, “Oh, your name is — You’re this, you’re that.” And I started to build these lives. And then I got a Guggenheim. And back in 2014, I got it. And my project was to do a series of poems accompanied by these photos, Germanic monologues, persona poems, things like that. And to have it have some sort of form. I still have slam hold in my head so much that I’m always looking, “How do I make that harder?” So it’s 40-something poems I think accompanied by the pictures and it’s called Unshuttered, and it’ll be out in February.

[applause]

Ó Tuama: Wonderful.

Smith: Thanks.

Ó Tuama: I think you’re going to read two, and we’ve got the photos. And actually, I’m curious whether before or after each photo if you could also tell us what you see in the photo.

Smith: Oh, sure.

Ó Tuama: I’m curious.

Smith: No problem. All right. So this photo, one of the places I used these photos was in my workshop at Cave Canem. And Cave Canem, I’m going to tell you the first time I started to work there as a faculty member, I walked into my first class. Who was in my first class? Tracy K. Smith, Jericho Brown, Ross Gay. [laughs] I’m like, “Are you kidding?” So we all had these photos. And Roger Reeves, who is a National Book Award finalist this year, was in my workshop. And he had written a poem, not to this picture, but to another picture. And the idea for this came from that. And I even contacted him and said, “I’m going to do this. I hope I do your poem justice. And I’m going to try another take on this.” And so I thought that just because we’re in the 19th century doesn’t mean that there weren’t people who had questions about gender identity. It was just very quiet. That there weren’t gay people, that there weren’t — So that was the reason I came into this.

“Conjuring a woman is maddening. Such feeble guarantees.

I dare first what is needed—the store-bought blouse, its

treasured frill and stiff curl of cotton. The bogus bar of gold

greening at my throat. I dare sugar in practiced poses while

three overlooked hairs waggle on my chin and light struggles

through these flawed hillsides of hair—hair oiled heavy

and patted toward a quite uncertain she. What a weak

and reckless way to step forward—sitting on my hands

to quiet their roped veins and ungirled work, hiding blunt

mannish nails, bitten just this morning to a troubled blood.

I hiss-suck every air while the button on my skirt strains

and my thick toes, accustomed to field, spread slow purple

and bawl in these beautiful borrowed shoes. I sit taller,

try to name myself crepe myrtle, camellia, burst of all hue.

“Tell me that I have earned at least this much woman. Tell me

that this day is worth all the nights I wished the muscle

of myself away. It will take my mother less than a second to know

her only child, her boisterous boy, steady pounding at his

shadow to make it new. Here I am, Mama, vexing your savior,

barely alive beneath face powder and wild prayer. Here I am,

both your daughter and your son, stinking of violet water.”

[applause]

Thank you.

Ó Tuama: The Greek word persona means mask. And in lots of drama, the mask wasn’t for hiding the truth but revealing it. And I’m so struck just this one small line toward the end of this poem, “Here I am Mama, vexing your / savior.” Sounds like you, especially for what you said earlier on.

Smith: Oh, now he’s like a psychiatrist. [laughter] “That sounds like that might be you and your mother.”

Ó Tuama: Well, there has to be some psychological draw to the known persona or even the imagined persona.

Smith: Yes. Yes.

Ó Tuama: How do you track that for yourself?

Smith: What’s really funny is how that stuff comes up. And when you said that, I went, “Oh, my God.” And I can’t say — it wasn’t on purpose, but the idea of the many ways I have vexed my mother’s savior in my life, and it has to do with revealing who you truly are. And I could have knuckled down and been the person my mother wanted me to be. God knows she tried and tried. But I’ll tell you the spirit, when you are leaning in this direction of, when you find a way to tell your own story, that’s a really strong spirit. And you’re constantly straining toward it and straining toward it. And some people that I know just never got there. But I think we’re really, really lucky. Bless my mom and everything, but thank God I found other mothers, other people who I could confide in, other places to go where their mothers were the same and we could talk to each other. And if I had not become a poet, I don’t think I would’ve found those people.

Ó Tuama: I wonder if you could read another one of those poems from this upcoming book. And is there a story about this image?

Smith: This is a daguerreotype. It’s not a tintype, it’s not a paper photo. It has a depth to it. And the pictures, even though they are black and white pictures. They do have tone. There’s like sepia and all that. And so the pictures will be in color. And this is a really wonderful burnished gold frame. There’s something about her blend of assurance and being tentative. Something about the, “I know who I am. I don’t really know who I am.” And the straight-on, just the straight-on.

“I could be your confounding daughter, wide-eyed in the ways

that puff your chest and make you keen to father me—

or a sibling, curling into sleep, deciding not to see.

Your awkward finger hovers, heats, then falls to stray.

“Let your imagination reckon on my name. Obsess

on facts a pining stranger seeks. You’re not exactly sure

if I’m a child—another gangly immature

rapscallion blooming new inside a Sunday dress—

“or if this coy and luminescent glare suggests

the hallelujah of a yes. I can endure

your stomach-churning, ill-considered hope—this lure

is snagged in history. Allow me to confess

“the women coiled inside my chest—unhitched from industry,

midnight and seething, ageless wailers. Their tenacious clutch

is all my body is. So when you wonder if your touch

will spark a smolder, we say yes. Come here. Come close to me.”

[applause]

Ó Tuama: I love how it goes from “I” to “we.” “I” at the start is the first word.

Smith: Well, I imagine because it was so soon after slavery, that every time I see a woman, I just automatically will see all these women behind her, and just like a straight path like, “How did you get to this space, little girl?” And they’re there. So a lot of it is, “When you are looking at me, you are not just looking at me.” And so that idea of strength. There’s just like anything else, there’s some weakness in some of the personas. There’s a strength. Some people are boisterous, some are tentative, some are telling a true story that happened at the time that the picture was taken.

Ó Tuama: We have time for a few questions. I wonder if there’s microphones up on either side. I wonder if people want to come up. Maybe share your name and then just launch right into your questions, so we can get as much from Patricia as we’re able.

Audience Member 1: Hi, my name is Marilyn. And on the one hand, I’m really intrigued by Unshuttered, but I’m also really troubled by it. Confession time, I’m not a poet. I’m a folklorist and anthropologist, and I do ethnographic work. So it’s fascinating to hear quote-unquote the stories of the people, but I’m really concerned, and maybe you can help assuage my feelings about this, that those were real people. And what then becomes attached to them are these other stories that are really not their stories? Thanks.

Smith: Uh-huh. Okay. All right. So in Blood Dazzler, there’s a long poem about the 34 nursing home residents that were lost, left behind when they thought, “Okay, here comes the storm. Someone will come and help them.” And they’re not going to. So my poem is like a camera lens going around the room, I’m stopping at these beds. And when — This sounds like it’s roundabout — but when my aunt was dying, she was in a nursing home. And I was young, I was in high school at the time, but we were all charged with her care. And I didn’t really know much about caring about her. She had lost her mind. And she was throwing food and feces and stuff against the wall. But every time, there was a yellow button by her bed. And when I needed help, I would press that button and someone would come.

So when I saw that story happening, I thought back and I said, “The water’s rising, the lights are out. And I can imagine the pressing of those buttons, and this time no one is coming.” So as I go around that room, I’m looking at the guy who is still wearing his military medals. These are people that when I was taking care of my aunt, I would go out and start talking to these people. The woman who put a full face of makeup on every day and just sat out in the lobby. And so I’m saying, and I think the same thing is with this, but at first, I was saying, “Let me see if I can find these families. Let me do this.” And when I’m talking about looking at other lives, and how valuable it was using them, even as a teaching tool — and when this book comes out, after every time I do a reading, I’m going to insist that there’s a question and answer because this is the kind of discussion that I want to have — I’m not saying this is the only thing that this person is. I’m saying this is a thing that this person may have been. I’m looking at the town that they’re in. I’m looking at the photography studio. Some of the poems are things that were happening in that town at that time, that this person would been privy to. So I try to move the lens in a real way as close as I can.

And at the end, there’s a poem at the end that is made up of all the first lines of the other poems. And that poem is about what you try to leave to us and how the many ways that we’re interpreting that. And we need to gather your voices again, bring them back to where we stand, and realize that we are built upon those voices. And it’s a communal poem.

So one of the things I’m saying is: yes, this may be somewhat this person or it may be your descendant or yours, but let’s turn around and look back at them in a real way and say, “Yes, what she’s saying is maybe this person at the time when they lived in the place where they lived, maybe they saw this event.” And then you say, “Oh, that event happened then? Let me look at some more of that.” Or knowing that the next time you see a picture from the 20th century like this that you will say, “In my head, I’m wild with imagination. I may be right, I may be wrong, but there are voices that I try to typify without getting too specific, but saying there were people who were gay, how much do we know about?”

So I’m taking the feeling I have from people I talk to now who are having issues being gay or coming out and thinking, “What was that like in 1872?” And say, this is a sample of what this voice might have been, but you look at it and tell me what you hear. And so it’s something that’s going to be evolving every time I talk about it because I need to talk about that because a lot of the work I do touches upon other lives. And one of the things we had to be sure of is when I was working on the book, somebody had seen — this was a story you may know about it, somebody had seen — because these photos are all free use at this point. Someone had seen a photo somewhere, a cabinet card or something, that was being used, not in an advertisement or something. And they were like, “Isn’t that grandfather?” And it wound up being that there were people who knew who that was.

And so the story of how I came to the pictures, the story of using them as a teaching tool to get people hooked in their history for a while, which could lead to other places, I’m thinking there is value in it. There will be people like you or other people who question — Like you said, first of all, I have to make sure that there is no argument with the work, with the poems themselves. Because you say, “I’m fascinated by this, but on the other hand…” And that’s what I expect because there’s a little bit of that in me too. I’m so glad you were the first question because that’s an issue. That’s an issue. And that’s how I feel about it. And I’m well aware that there’ll be other people who may feel otherwise. And it’s good.

Ó Tuama: Other questions?

Audience Member 2: Yes. I’m Wendy, and I have a question about Unshuttered as well. So I was wondering, given what you just spoke about, a lot of docu-poetry kinds of books, whether they’re prastic or not, will have a forward to contextualize what the reader’s about to experience. So I was just curious if there’s a forward and what the content of that might say. And then also in these times, if you used any photographs where you had had contact with the families, did you incorporate any of the stories, anything they told you about the person? Or did you stay away from those photos and use different ones in your collection?

Smith: Okay. There is a forward. It’s very much what I’ve said here very much about how I happened upon the photos, thanking the people at Cave Canem for helping me realize what amazing tools they could be for teaching. And the fact that there is one photo, I don’t know where the descendants are. We would run the names when there was a name written on the back or something. And one we found the son of a man who had spent months in the hollowed-out trunk of a tree after escaping slavery. And he was a freed man. His son lived in Syracuse, New York, was posed there with his wife. And so I took that opportunity to tell his father’s story and to have him be amazed and have the same kind of tree growing on his property and wondering how his father, how did he face day after all those months. And there was documentation about his father fighting off snakes that crawled into the tree, what it was that he ate, sprouted taters, and things that he ate. So I was really happy to have that information and able to have his son come forward with a true story. And I mentioned that in the — although we had tried to find the backdrop of so many people, that that one, a story came to the forefront and we used it.

Audience Member 2: That gave me goosebumps. Thank you.

Smith: Oh, no problem at all.

Ó Tuama: We could talk all day. A phrase that you use a lot when you speak about poetry is particular “skills in your toolbox.” And I’m struck by how for you, the toolbox is a box of craft and writing and form, but also a toolbox about what does it mean to be a citizen? What does it mean to look? What does it mean to pay attention and to consider what it means to be alive?

Smith: Walk through the world as a poet. What does it mean to walk through world as a — We should all be certifiably in sync. Every time we open a door and we step — Before we open the door and we step out, there are stories, lines, poems hurdling at you in all directions. And when you get to the point where you realize that there’s nothing like it. Every morning the slate is clean, you don’t know what the story’s going to be, you don’t know what that line is going to do, you don’t know — Who else lives like that? Who else lives like that? And so we are so blessed not to — the books and all that. Like I said, I always ask, if there were no books and no stages and all that, would you still be writing? And ask yourself that everywhere along the line. Am I writing for fame? There’s nothing wrong with that. Am I writing to move myself sanely from day to day? Is this a recreational activity? And then realize that you have taught yourself the best way there is to look at the world. And it’s not easy sometimes because that means you see everything a little bit more clearly and that includes the good stuff and the bad stuff. But what better way to live than what we’re doing right now?

Ó Tuama: What a way to finish. Patricia Smith, thank you so much for the brilliance of your work.

[applause]

Smith: Thank you. Thank you.

Ó Tuama: What joy to be here with you.

Smith: Thank you, guys. Oh, and if anybody else wants to ask a question or wants to talk about the book or you want to punch me or something, I would really appreciate that. Thank you again for that. All right. Thank you, people.

Martin: Pádraig Ó Tuama and Patricia Smith, thank you so much. We thank all of you.

Smith: That’s so much fun. I’m jealous that you’re talking to other people.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.