Caroline Bird

Little Children

Children’s demands can be high, and their standards can be exacting. It’s a good thing they’re loveable.

We’re pleased to offer Caroline Bird’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Caroline Bird grew up in Leeds, the daughter of noted theater director and producer Jude Kelly. Bird’s first collection of poems, Looking Through Letterboxes (2002), was published when she was just 15. Her other collections of poetry include Trouble Came to the Turnip (2006); Watering Can (2009); The Hat-Stand Union (2013); In These Days of Prohibition (2017), which was shortlisted for both the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Ted Hughes Award; and The Air Year (2020).

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and once, when I was seven, I think, I was telling my mother some endless story while she was trying to get the shopping done in a supermarket. And she turned to me and said, “Pádraig, I don’t give a shit.” And I was aghast. As far as I was concerned, that is a terrible thing to say to a child. [laughs] And I said it to my brother later on that night, to go, “Mum said to me she doesn’t give a shit about my stories.” And my brother laughed more than I’d ever heard him laugh, at that stage in our small lives.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Little Children” by Caroline Bird:

“Politically they’re puritans.

They gasp at nudity like it’s 1912.

They’re shocked by minor offences

such as chip stealing. 98% possess zero faith

in the concept of rehabilitation for adults.

As far as little children are concerned

forgivable mistakes occur before sixteen,

after that you’re on your own. Their stance

against marital infidelity is Victorian and their

position on divorce aligns with the Vatican City.

Nuance is irrelevant to the infant moralist.

They sit in plastic umpire chairs at the dinner table

shouting out unintelligible scores. They’re violent.

They’ll head-bang a breast or stuff a sticky hand

up a skirt then just amble away

like raging misogynists. They won’t even allow

their mothers to bring home a sexy stranger

on a Friday night. They disapprove of drugs

like Tory neighbours. Their standpoint on drunkenness

is predictably brutal, especially for women.

It’s like the sixties never happened. They believe

every adult should be locked into a sexless yet eternal

marriage, never slip up or forget

even a lunchbox, and be completely transparent

and open to feedback 24/7. They’re hypocrites.

They spy on you in the toilet. Parents aren’t permitted

even the smallest private perversion yet a child

can secretly urinate in a drawer for three weeks

until the smell warrants investigation.

Their relentless indignation! Their fascist vision

of the perfect family! Little children are like

the tsarist autocracy of pre-revolution Russia.

Their soft hands have never known work.

Their reign is unearned.

“On behalf of my younger self I apologise

to my parents for the simplistic, ill-informed

and ignorant questions I hurled concerning

their romantic and sexual life choices.

How could you do that to dad?

How could you do that to mum?

I was operating under a false consciousness,

responding to an imagined society governed

by laws I’d gleaned from picture books

about tigers coming to tea. I had no right.

No credibility. Imagine bellowing criticism

from the stalls after seeing two minutes of a play!

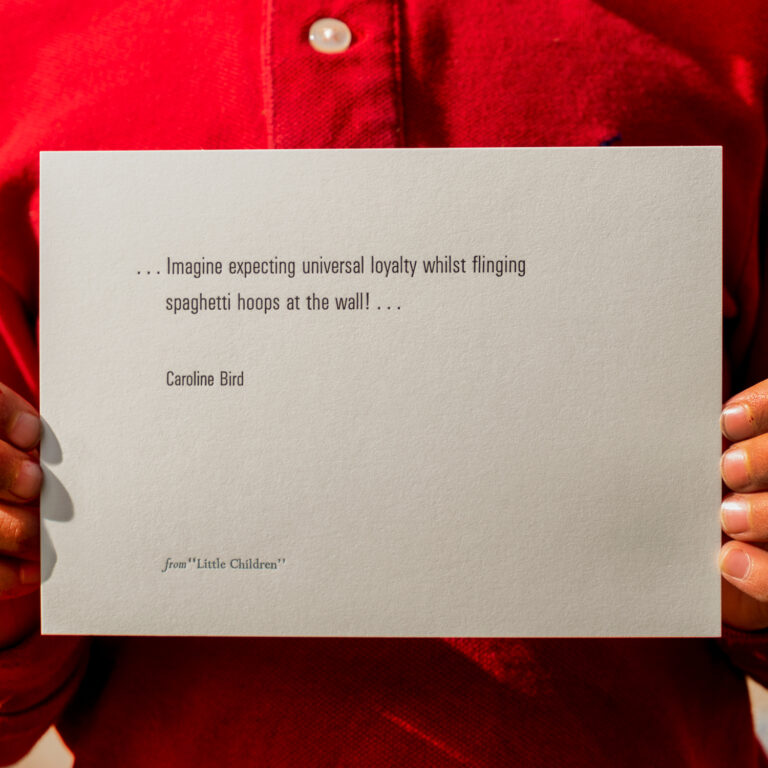

Imagine expecting universal loyalty whilst flinging

spaghetti hoops at the wall! Imagine having such

confidence in your innate philosophy of love!

“We kneel to tie the laces of their unfeasibly tiny shoes.”

[music: “Idle Ways” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I absolutely love this poem. I think it’s hilarious. Initially, you’re reading it, going, You can’t say that about children! You definitely can’t say that. Oh my God, you just called them “autocracies.” You can’t call them that.

The whole thing builds up like a piece of theater. True enough as it is, I think lots of people would go, My God, yeah, wait’ll you hear the story about my little one.

And then the poem turns: “On behalf of my younger self I apologise.” And it sounds like the speaker in this poem is reflecting on their life as a young person, as a child, and realizing that, as a result of becoming a parent themselves, that they want to apologize; that they’re suddenly seeing the standards that they held their parents to, when they were a child, are exhausting and tiring and nowhere near as reasonable as it seemed to them, when they were a child. Having received it, they now wish to go back in time and find a way to apologize to the parents, who seem much more reasonable now that you’ve become one than they seemed when you were just their child.

[music: “Dust of Summer” by Gautam Srikishan]

The opening part of this poem is a magnificent sequence, a litany of all kinds of accusations to children, saying that they’re puritans and unforgiving, that they’re cynical about adults’ capacity to change and that they hold adults to account, that they’re unnuanced and that they watch adults, they’re violent, they’re intolerant of the sex lives of their parents and disapproving, that they can be hypocrites and that they can be entitled, because they’re entirely focused on the self. And it’s funny, because it’s true. And I can imagine, if a four-year-old or a three-year-old were able to understand this poem, that they might go, Yeah? And? What’s the big deal? Like, that’s the whole point of being my age.

All of these things are true and recognizable, but what’s interesting is that underneath all of those is this phenomenal patience, because at no point is the person in the poem implying that, OK, I want out — I want to give my children back to the children farm.

The poem here has an underlying stream of love within it, and that is held together in two ways, particularly. At the turn of the poem, when she wants to apologize to her parents for her own “simplistic, ill-informed, / and ignorant questions I hurled concerning / their romantic and sexual life choices,” there’s great love in that. And then, also, in the very final line, “We kneel to tie the laces of their unfeasibly tiny shoes,” in that line there’s such devotion and almost fealty. You know, the poem has playfully implied that children can be like autocrats, and here “[w]e kneel,” almost like a subject kneeling before their monarch. And that’s playful. It’s picking up on the whole idea. It’s entering into the world of demand that a child gives, but doing it in a way of this beautiful love — “their unfeasibly tiny shoes” — looking at the smallness of their feet and knowing that those feet will only be small for a small amount of time.

[music: “Daybreak” by Gautam Srikishan]

Time is a fascinating feature in every poem. If I could write one book of theory approaching the question of a poem, I would want to look at how does time function in a poem, because in a poem, it’s almost like the big bang is happening, because time’s going forward and backward and outward and inward; everything is there, working in on itself. And in this poem time is an extraordinary critique, because Caroline Bird says, “Imagine bellowing criticism / from the stalls after seeing two minutes of a play!” And what she’s saying is there is a need to find a relationship with time, to know how to judge what’s happening in one moment, in light of perspective.

You could almost say that this poem is like an extended sonnet, with a volta in the middle of it, because of that turn that happens when she turns to her parents — “On behalf of my younger self I apologise.” It makes me wonder how much of the first part of the poem is Caroline Bird describing her own experience of being a parent, or her own experience of having been a child. And I think mostly it’s the latter — that she’s reflecting on herself, the way that she had “zero faith” in the “rehabilitation of adults” and thought that, well, children are allowed to make mistakes, but you’re a grownup, and so therefore, you are not.

This is not a poem about four-year-olds not understanding adult relationships. And I also don’t think it’s a poem just about 34-year-olds or 64-year-olds. I think this is a poem about finding a way to live with time and to make the changes in your life that time and perspective demands. It’s a dynamic poem. And it’s asking — and praising, really — the possibility of dynamic living, of seeing old things in new ways, and hopefully having enough relationship with people through decades of life to be able to say, oh, I’m seeing this in a new way now. Maybe you could fantasize about a world where everything would be seeable to you when you’re 12 or 20 or 30, but that isn’t the world that’s being praised in this poem. The world that’s being praised in this poem is a world of parents who love their children and of children who learn how to love their parents back, especially as they age.

[music: “Gambrel” by Blue Dot Sessions]

One of the things that happens in this poem is that by parenting a child who is learning how to discover what does it mean for them to say, “I am me, and I am we, and I am one of us” and learn how to be a human in the world, is that the parent is learning how to be a human in the world, here, too. This poem is so much about discovering what love looks like when you’re loving people at different stages and ages of their life, including yourself, including yourself as a new parent, including apologizing to your parents, including learning the things that only time will teach you.

[music: “Gambrel” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Little Children”:

“Politically they’re puritans.

They gasp at nudity like it’s 1912.

They’re shocked by minor offences

such as chip stealing. 98% possess zero faith

in the concept of rehabilitation for adults.

As far as little children are concerned

forgivable mistakes occur before sixteen,

after that you’re on your own. Their stance

against marital infidelity is Victorian and their

position on divorce aligns with the Vatican City.

Nuance is irrelevant to the infant moralist.

They sit in plastic umpire chairs at the dinner table

shouting out unintelligible scores. They’re violent.

They’ll head-bang a breast or stuff a sticky hand

up a skirt then just amble away

like raging misogynists. They won’t even allow

their mothers to bring home a sexy stranger

on a Friday night. They disapprove of drugs

like Tory neighbours. Their standpoint on drunkenness

is predictably brutal, especially for women.

It’s like the sixties never happened. They believe

every adult should be locked into a sexless yet eternal

marriage, never slip up or forget

even a lunchbox, and be completely transparent

and open to feedback 24/7. They’re hypocrites.

They spy on you in the toilet. Parents aren’t permitted

even the smallest private perversion yet a child

can secretly urinate in a drawer for three weeks

until the smell warrants investigation.

Their relentless indignation! Their fascist vision

of the perfect family! Little children are like

the tsarist autocracy of pre-revolution Russia.

Their soft hands have never known work.

Their reign is unearned.

“On behalf of my younger self I apologise

to my parents for the simplistic, ill-informed

and ignorant questions I hurled concerning

their romantic and sexual life choices.

How could you do that to dad?

How could you do that to mum?

I was operating under a false consciousness,

responding to an imagined society governed

by laws I’d gleaned from picture books

about tigers coming to tea. I had no right.

No credibility. Imagine bellowing criticism

from the stalls after seeing two minutes of a play!

Imagine expecting universal loyalty whilst flinging

spaghetti hoops at the wall! Imagine having such

confidence in your innate philosophy of love!

“We kneel to tie the laces of their unfeasibly tiny shoes.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Little Children” comes from Caroline Bird’s book The Air Year. Thank you to Carcanet Press, who gave us permission to use Caroline’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.