Chris Abani

The New Religion

How do you speak of — and to — your body?

This is a poem dedicated to the body. “The body is a nation I have not known,” Chris Abani writes. Throughout the 21 lines of this work, he describes lungs, skin, bone, touch, smells, sweat, armpits and hunger. For all the embodiedness of the poem, there is disembodiedness too: the poem continues to question how to truly be in your own body.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

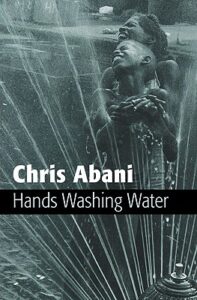

Chris Abani is a novelist, poet, essayist, screenwriter and playwright. Born in Nigeria to an Igbo father and English mother, he has lived in the United States since 2001. He is Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University. His poetry collections include Sanctificum and Hands Washing Water.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and poetry, for me, is not an escape from the world, but an embrace of it. Poetry isn’t the final end, in and of itself. Poetry is a way to open myself up to being alive in the world, in my body and in my words and in my mind.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The New Religion” by Chris Abani:

“The body is a nation I have not known.

The pure joy of air: the moment between leaping

from a cliff into the wall of blue below. Like that.

Or to feel the rub of tired lungs against skin-

covered bone, like a hand against the rough of bark.

Like that. ‘The body is a savage,’ I said.

For years I said that: the body is a savage.

As if this safety of the mind were virtue

not cowardice. For years I have snubbed

the dark rub of it, said, ‘I am better, Lord,

I am better,’ but sometimes, in an unguarded

moment of sun, I remember the cowdung-scent

of my childhood skin thick with dirt and sweat

and the screaming grass.

But this distance I keep is not divine,

for what was Christ if not God’s desire

to smell his own armpit? And when I

see him, I know he will smile,

fingers glued to his nose, and say, ‘Next time

I will send you down as a dog

to taste this pure hunger.’”

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I love this poem for the way in which he explores his own relationship with his body and tells us, really, that there’s been a distance in him between his mind and the way his mind talks about his body, as if his mind isn’t part of his body. And I think this is a very masculine poem; I think this is a poem written by a man reflecting on his relationship with the body, his relationship with ease.

And then he speaks about the body being a “nation” and being “pure joy,” and he speaks about the exhilaration of leaping and the thrill of it all. And then he speaks about his experience of the body as having been something that spoke of his body as a “savage.” And he repeats that: “the body is a savage.” And he speaks about seeking safety in the mind. And then he says that it’s cowardice that has kept him from being overly present to his body. It speaks about being present to the body and the shout and the whoop and the joy of it all, and the movement of it all, and the fluency of it all. It speaks about that as vulnerability and that, to face into the anxiety of that, he instead has sought safety. And he has called that safety “virtue,” instead of realizing, as he’s saying very vulnerably here, it’s cowardice. He hasn’t known how to risk what it means to be present in the body. And he has sought safety in the mind when the risk of being in the body has been present there.

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Sometimes people would ask me the question of, “Are you a head person or a heart person?” And I never liked the question, but it took me a long time to define why I didn’t like the question, because I don’t like the idea that you have to be one or the other. And, also, I don’t like the imagination that those two are necessarily so divorced. Both the head and the heart, the mind and the feelings, they all take place within a body. If you didn’t have a body, you wouldn’t have those things. And so the question is, what is your body saying, and how are you listening to your body? And sometimes that might be intuition, sometimes that might be analysis; if you’re feeling led by your feelings, that can be as intellectual as being led by rationale.

And I think I’ve always felt like I don’t fit in the imagination about what a man should be like, when it comes to talking in public. And I always felt like that was being used as a slur against me. But I recognize the way that Chris Abani writes here about the deep divide that he’s felt and the need that he’s felt to reconcile those things, and the wish, almost, to have another go, the wish to have a better go at being present to your body without apology.

Similarly, in the way that Chris Abani brings in questions of religion, I think there can be an anxiety about the carnality of the body. There can be an anxiety about being present to sex, about enjoying the sexual language of your body and owning that. “Carnal” comes from the word “carne,” in Latin, meaning meat. And it’s a fascinating thing, to be so uncomfortable with the meat of your own body. And the invitation that he puts forward in this, through the mouth of a God who’s got an armpit and is smelling his own fingers, the invitation in this poem is to be present to the meat of your own body and how the meat of your body is filled with its own hunger.

[music: “Kid Kodi” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ó Tuama: There’s a couple of technicalities within the poem that are quite brilliant. For Chris Abani, the experience of embodiedness is about the joy of jumping and feeling your lungs, your filled lungs, press up against your ribs, and feeling the rub of hand against your own skin, and having the smell of yourself when you were young and exuberant and exhausted, and exhausting, probably, and the feeling of sweat and dirt on your own skin, when you were younger. He speaks the whole way throughout this poem about parts of the body: lungs, armpits, bones, hands, rubbing your body, the smell of your body, your dirty, sweaty skin, your own armpits, your smile, your nose, taste, and hunger. This is a poem that’s filled with the reality of having a body. And the poem is trying to figure out how to get to it, using thoughts and the mind.

Chris Abani is a Nigerian man with an English mother, and he’s regularly been told things about his face that make him think about his face. He’s written an entire essay about it. And I think that line in this poem, “the dark rub of it,” is bringing us into that question about how he’s using the word “dark.” In one of his writings, in the essay on his face, he has a line where he says that when he tells people that his father was Igbo from Nigeria and his mother a white Englishwoman, people pause and give him a look that says, “Are you sure? You’re so dark,” as if he doesn’t know where he’s from. And he, in his own home country, in Nigeria, he’s perceived, often, as being from all kinds of other places, not necessarily Africa. He’s been considered Lebanese and Indian and Fulani and Arab. But not in England or the US, where he’s spent a lot of his life. There, he’s often spoken of as being firmly Black. And so this usage of the word “dark” there is doing so much work in his poem, “the dark rub of it.”

The title of this poem, “The New Religion,” this poem could’ve been called so many things, “About the Body” or “The Dark Rub of It,” or it could be called “The Rough of Bark.” “I Am Better, Lord.” There could be so many elements of that poem that could’ve been lifted up for the title, instead of which this title stands alone. It points the direction that this poem is facing in, which is a religion that pays attention to the body and a religion that is en-fleshed, a religion that is holding itself in meat.

And you even see that the poem tries to do that, when it says, “like a hand against the rough of bark. / Like that.” The way that he speaks about “leaping / from a cliff into the wall of blue below. Like that.” And then, “’The body is a savage,’ I said. / For years I said that: the body is a savage.” This poem is talking to itself. This poem is trying to bring the embodied memory of being back to itself and confront itself. This is the new religion, I think, that the poem is proposing: to be present to yourself in the fullness of your own body.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

“The New Religion” by Chris Abani:

“The body is a nation I have not known.

The pure joy of air: the moment between leaping

from a cliff into the wall of blue below. Like that.

Or to feel the rub of tired lungs against skin-

covered bone, like a hand against the rough of bark.

Like that. ‘The body is a savage,’ I said.

For years I said that: the body is a savage.

As if this safety of the mind were virtue

not cowardice. For years I have snubbed

the dark rub of it, said, ‘I am better, Lord,

I am better,’ but sometimes, in an unguarded

moment of sun, I remember the cowdung-scent

of my childhood skin thick with dirt and sweat

and the screaming grass.

But this distance I keep is not divine,

for what was Christ if not God’s desire

to smell his own armpit? And when I

see him, I know he will smile,

fingers glued to his nose, and say, ‘Next time

I will send you down as a dog

to taste this pure hunger.’”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “The New Religion” comes from Chris Abani’s book Hands Washing Water. Thank you to The Permissions Company on behalf of Copper Canyon Press who gave us permission to use Chris’s poem.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.