Columba Stewart + Getatchew Haile

Preserving Words and Worlds

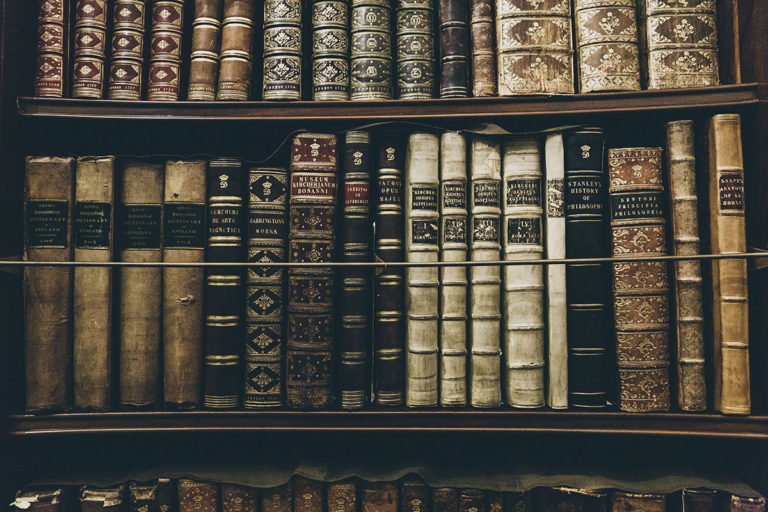

Saint John’s University and Abbey in rural Minnesota houses a monastic library that rescues writings from across the centuries and across the world. There are worlds in this place on palm leaf and papyrus, in microfilm and pixels. And the relevance of the past to the present is itself revealed in a new light.

Image by Thomas Kelley/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

Columba Stewart is the executive director of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library at Saint John's Abbey and University.

Getatchew Haile is a MacArthur Fellow and the curator of the Ethiopian Study Center at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library at Saint John's Abbey and University.

Transcript

May 6, 2010

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today we travel to a monastic library that rescues writings from across the centuries and across the world. And in this work, the relevance of the past to the present is itself revealed in a new light.

FATHER COLUMBA STEWART: The real thrill is the poignancy of the moment of trust and the awe of being shown what these people hold most precious and what they really suffered to keep.

THERESA VANN: You know books are the highly portable artifacts. They’re very stable artifacts, and yet they are a great window to the past.

GETATCHEW HAILE: Well, every morning when I come to my office, I open a raffle ticket, you will say, when I open a manuscript. I come with such great curiosity and anticipation. What am I going to see in here?

MS. TIPPETT: This is On Being. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Across Europe’s Dark Ages, Benedictine monks hand-copied Latin and Greek texts from literature to mathematics, from philosophy to theology, literally helping to sustain Western civilization. And a thousand years later on a stretch of Minnesota prairie, Benedictine monks and photographers and scholars tend the world’s largest digital archives of medieval manuscripts and a vast repository of written living memory from endangered cultures around the world.

There are worlds in this place on palm leaf and papyrus as in microfilm and pixels. We explore this with the monk who directs the library and an Ethiopian scholar who’s led some of its most intriguing work. In their lives, the relevance of handwritten manuscripts to the present and the cultural cargo of the past are revealed in a new light.

From American Public Media, this is On Being, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Preserving Words and Worlds,” our 2009 exploration of the work of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

Saint John’s Abbey and University, where the Hill Library is based, visually fuses a reverence for tradition and an embrace of modernity. Turn off a nondescript Midwestern exit from the I-94 and it’s Bauhaus chapel appears on the horizon. It was designed by the Hungarian architect Marcel Breuer, commissioned by the monks of St. John’s in the 1960s. They created the manuscript library in the same period with an eye at that time to the Cold War threat to ancient European monastic repositories. Today, the library’s work spans far-flung geographies, enjoining local partners from Ethiopia to Ukraine, from Lebanon to India.

Unlike printed books, manuscripts are one-of-a-kind relics. And for the endangered communities around the globe who seek this place’s help, manuscripts are fragile links to a history they’ve kept alive in the face of civil wars, the appetites of commercial tourism, and even the appetites of rats and insects.

FR. STEWART: It’s kind of thrilling in the adventure sense, but the real thrill is the poignancy of the moment of trust and the awe of being shown what these people hold most precious and what they really suffered to keep. And that’s extraordinary.

MS. TIPPETT: Father Columba Stewart is the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library’s current executive director. He wears the traditional black habit that is commonly worn among the monks of this community. And we sit down to speak in the gallery space of the library’s sleek austere structure. We’re surrounded by oversized pages from a lavishly illuminated handwritten Bible, a contemporary work in progress being overseen by the Queen of England’s calligrapher. And Columba Stewart has brought with him some centuries-old relics from the library’s archives, visibly marked by the passage of time. He grew up in Houston, studied at Harvard, and would have been a college professor, he tells me, if he’d not become fascinated by monasticism and captured in particular by the Benedictine ethos of Saint John’s.

FR. STEWART: I was drawn to the way the liturgy was celebrated. I was drawn to the intellectual vitality of the place, and I just liked the spirit in the house, all these intelligent, really funny people. I mean, funny in the sense of humorous, and witty, and I liked the fact that we did things like this manuscript project. You know, we dress like this, but usually there’s a cell phone in my belt, so how we put that together I think is one of the great Benedictine stories because it’s not just a 21st-century effort to bridge this.

But Benedictines were early adopters of all kinds of technology, whether it was timekeeping technology, so we got up on time for the liturgy, or printing in the 1450s. People think that we would have been naturally resistant because we had such an investment in copying manuscripts, but when somebody came along and said there’s an easier way to do this, we loved it. And equally with the microfilm. Microfilm seems antique to us now.

MS. TIPPETT: It was avant-garde then, wasn’t it?

FR. STEWART: Yeah. In the ’60s, it was cutting edge, and convincing an Austrian abbot that he should let us into a medieval or baroque library to use this ungainly modern microfilm equipment to shoot medieval manuscripts was really a dramatic intrusion of modernity for them. But, of course, as Americans, we’re very American in our embrace of technology, even as we were also Benedictine in an openness to connecting the tradition with technology.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. So let’s define manuscript. What is a manuscript?

FR. STEWART: Well, literally a manuscript is something written by hand, so it would be handwritten things considered to be of historical importance, whether regarded as historically significant at the time they were written, like chronicles or lists of important figures or something, or regarded by later people as of historical significance.

MS. TIPPETT: But also because of the nature of them physically, as you say, they also are carriers of more than just the text that’s in them. You use this phrase, “the stickiness of manuscripts.” What do you mean by that?

FR. STEWART: Well, this is one of the interesting evolutions in a way that’s happened in manuscript studies because an earlier generation of scholars thought of manuscripts in terms of the fact that they carried texts, and the actual words of a text were what mattered. The carrier might be of interest to some, but was really less significant than the text itself. Whereas more recently scholars have recognized that manuscripts also preserve the context in a way that printed books simply don’t.

So the way it’s bound, the marginal notes, the ownership inscriptions, the comments about the weather or who was king or the kind of fabric that’s used to line the book, all of these things become clues then to the community which produced it and then the communities or individuals who owned it. So our transition from the old black-and-white microfilm photography to the high-quality color digital is important because we can look at all that stuff.

WAYNE TORNBORG: I want to do what’s called remote capture, which opens up a little control panel on my computer and actually this controls …

MS. TIPPETT: Wayne Torborg is Director of Digital Collections and Imaging at the Hill Library. He has set up digital studios and trained local partners in Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Here he demonstrates the technical process of digitizing an 18th-century manuscript from Ethiopia.

MR. TORNBORG: If this is all set up — and this is like Julia Childs, of course. We set the bread up in the oven and then we open the door and we pull the bread out after, you know, going through all the motions — this should fire the camera. So here is basically a view of our manuscript. The detail is actually incredible compared to, for example, have you seen much bitonal microfilm, which is everything’s either black or it’s white. There’s a couple maybe shades of gray, but not much. Things like red lettering, which many manuscripts have, get lost. Anything that’s blue gets lost immediately because black and white is very sensitive to blue, so it sees it as white generally. Fine writing, hairline serifs …

MS. TIPPETT: It’s actually quite difficult, I think, for a 21st-century American or probably European as well to even imagine the value people would invest in these written manuscripts. Tell me what it means when you have gone to cultures where they have scribal traditions, where people are still living with manuscripts in a way that is just completely beyond our imagination now.

FR. STEWART: Well, in the West, the connection with manuscript culture was broken largely by the invention of printing, but also by what happened in Europe with the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, the suppression of monasteries. All of this led to manuscripts becoming things that were found in essentially state-run research libraries.

MS. TIPPETT: So again, taken away from the guardians and really losing the meaning that had been invested in them.

FR. STEWART: Exactly. And as I’ve, you know, said to people, even the guardians, even church groups, weren’t really interested in them, because they had no particular use for them. They had moved to printed books themselves. In the Christian East, on the other hand, manuscripts have remained in use even to this day in some areas like Ethiopia, parts of Syria and Turkey. But even where they no longer actually use the manuscripts, it is a tangible link for them to a tradition which at one time was much more robust than it is now. And in some cases, a collection of manuscripts is the only remnant of a community which no longer exists. And the manuscripts from a particular place have been taken somewhere else and taken there when they left everything else behind, because that was the living link.

So to see those collections and to hear people talk about even within living memory the story of how manuscripts went from one place to another, what happened to the original town or village where those manuscripts have been, meeting people who belong to a transplanted community, many of whom can’t read these things at all, because they’re written in a classical liturgical language, but who nonetheless regard these things as holy objects. So they’re profound bearers of cultural significance, and in some of these communities — certainly true of the Armenian tradition — these really are venerated as sacred objects, as we might venerate a relic or an icon or the Blessed Sacrament or something like that.

MS. TIPPETT: Really. You tell the story in one of the essays you wrote about coming across some young children and a monastic teacher.

FR. STEWART: Oh, this was unbelievable.

MS. TIPPETT: Was it Ethiopia?

FR. STEWART: It was in Ethiopia, northern Ethiopia in a little town called Yeha, which now is way out in rural Tigre Province. At one time, it was the capital of Ethiopia before Aksum became the capital. So we turned out, a group of 10 or 12 of us, board members of the library and myself, and we just wanted to see the place. We arrive and get off the minibus, and there was a couple of kids basically sitting in the dirt with a big manuscript — which is probably half the size of one of the kids himself — propped up on his knee, and he’s reading aloud.

And around the corner — sitting in the shade, under a tree — is a monk with another copy of the same text, and the boys are learning how to read Ge’ez. So it’s not their modern language; it’s their church language. But they’re learning to read it for church just like their fathers did and fathers before that, and they were using a manuscript. They were actually doing it the way all of us used to do it in terms of learning these traditions. So it was an astonishing moment.

I’ve seen other things. I’ve met people who wrote manuscripts at least when they were younger, when in their churches like in southeastern Turkey, manuscripts were still being copied. I’ve seen places in Armenia where manuscripts come home to a church, which used to own it before the communist era when all the manuscripts were taken away, and people mobbing the manuscript. They want to touch it as if it were some incredibly important relic or if it were, you know, some incredibly famous pop star or athletic figure today in a Western context, and they all want to touch it. It’s a tiny little manuscript. It’s nothing impressive or particularly significant as such, but for them, it’s the focal point of their history and their tradition.

MS. TIPPETT: Historian Father Columba Stewart. I’m Krista Tippett, and this On Being from America Public Media. Today, “Preserving Words and Worlds.” We’re at one of the world’s leading centers of photographic preservation of manuscripts that Columba Stewart directs, the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library known in short as HMML. He brings out a few samples of the library’s treasures when I speak with him here. You can actually see them and watch them described for yourself at speakingoffaith.org. Among them is a text on what looks like leather held between pieces of wood that emerges from a manmade pouch and comes, Columba Stewart tells me, from Ethiopia.

FR. STEWART: Ethiopian manuscripts often have these carrying cases, which are used to sort of sling it over your shoulder. And the great thing about Ethiopia today is, while manuscripts are not written as much as they used to, only in a few places, they still sell these little book covers for people to put their Bibles in.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s really kind of like a leather purse.

FR. STEWART: Yeah, exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s what it looks like. A shoulder bag.

FR. STEWART: Yeah, exactly. And often there’s a flap and you can see this one has been repaired, and it’s been kind of charmingly repaired with a little piece of leather. They haven’t taken the fur off. So we love to share this one.

MS. TIPPETT: So this looks like something you might see on National Geographic that was found in a cave.

FR. STEWART: Exactly, exactly. And it’s a classic Ethiopian style manuscript.

MS. TIPPETT: How old is that?

FR. STEWART: This one is 18th century. In terms of the way it’s put together and designed, it could also be 20th century. It’s just that this one shows from the style of writing and the wear …

MS. TIPPETT: So it’s just a wooden cover?

FR. STEWART: It’s a wood cover, and you can see it’s even a wood cover that’s been repaired, because it’s split along the grain. And it’s made up as all manuscripts are: You take a few pieces of paper and you fold them over and stitch them and then you stack those folds and then you stitch those together. This one, like many Ethiopian manuscripts, doesn’t have a leather cover on the back like our books do, so you can see the infrastructure, the binding. But you look at a manuscript like this and you can see that this was one that was really used. The edge of the page has been repaired where it was turned. These are protective kind of chamois end papers.

FR. STEWART: This is made out of vellum. So this is treated animal skin like many of the Western manuscripts and some Eastern ones. And they reused a page from a 16th- or 17th-century manuscript, so this might be a replacement manuscript. They reused an old page as a kind of flyleaf, which is very common, and then the manuscript itself. You can see that it’s blackened from the oil on fingers as the pages have been turned. This is the Book of Psalms, which is the most commonly found Ethiopian manuscript. And it’s also been close to the fire. You can see the little edges where somebody left it next to the campfire one night. It smells of fire. And the text is written in the classical way. Just like all of the manuscripts we work with, somebody went through and lined out all of the writing. You can also see the pinpricks on the side, which were used to hold it down and to measure the lines. Then, using black ink and red ink for headings, the manuscript itself.

MS. TIPPETT: What language is this?

FR. STEWART: This is in Ge’ez. It’s a Semitic language, so it’s in the same broad family as Hebrew and Arabic and Syriac. So this is a great artifact, because, again, you see all sorts of little bits about people who owned it, extra text they’ve written at the end, doodling.

MS. TIPPETT: A little doodle, yeah.

FR. STEWART: In a modern ballpoint pen or felt tip marker from somebody, you know, maybe as late as the ’60s or ’70s.

MS. TIPPETT: And when I look at this, I can actually imagine that people would crowd around it and want to touch it.

FR. STEWART: And a lot of people did. Obviously, somebody’s kids got hold of it because there’s all sorts of doodles in it. So you find something that had been in the family, like a family Bible, the difference being that this was probably used quite regularly until fairly recently. Now when we talk about the Eastern Christian manuscripts and some of these issues of changing cultures, one of my favorites in our collection is a manuscript from Egypt, which is actually written in Greek. It uses a Coptic-style alphabet, but it’s actually written in Greek, and it has an Arabic translation. It’s from the 14th century, written in Egypt for a monastery.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, over to the right. That’s parallel.

FR. STEWART: Over to the right, so you have a parallel translation. It’s interesting for all kinds of reasons. By the 14th century in Egypt, the Christians, who may centuries before have used both Greek and their native language of Coptic, had long forgotten Greek, but they kept copying Greek text because those were important for their history. So somebody copied out this Greek text of the liturgy, and it’s full of misspellings and they’re misspellings that would be made by somebody who didn’t really know Greek so well, was a Coptic speaker.

But because, of course, Greek was no longer known, they provide it with a parallel translation and they use Arabic because that’s the language by the 14th century. Even though Coptic was their church language, Arabic was the language they spoke all the time. So it’s, again, a reminder of these layers of culture and changes in language and culture and the fact that there is this flourishing Christian-Arabic tradition, which is rooted in these pre-Arabic Christian cultures, but which uses Arabic today as its common language, and this manuscript typifies that.

MS. TIPPETT: Hill Museum and Manuscript Library Executive Director Father Columba Stewart. One of his colleagues, Getatchew Haile, carries an intimate sense of the meaning of this work in his person, the cultural and even geopolitical implications it can have, especially for post-war and post-Colonial peoples with the task of recovering their own identity. The library’s work in Ethiopia has been among its riskiest, most intriguing and potentially most important both historically and theologically. Ethiopia is a source of some of the world’s most ancient Jewish and Christian traditions. In relative isolation, they’ve maintained original practices across the centuries.

Getatchew Haile, who is a linguist, was an early participant in the project to preserve, catalog, and analyze Ethiopian manuscripts after Ethiopian Orthodox Church leaders invited the Hill Manuscript Library to work with them in the 1970s. Then during a period of political instability, Getatchew Haile, who was also a member of the Ethiopian Parliament, was shot by government soldiers, and he has been in a wheelchair ever since. He and his family relocated to the U.S. with the help of Saint John’s Abbey and University and the Manuscript Library, so he continued his work on the manuscripts of his people from central Minnesota.

Getatchew Haile has been awarded a MacArthur “Genius” Grant for his accomplishments as a philologist and linguist. He wasn’t at the Hill Library the day we visited so I spoke with him later from a broadcast studio.

MS. TIPPETT: It sounds to me like, when you were still living in Ethiopia at the earliest stages of the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library’s work, they found you, and you were already at that time engaged in preserving these manuscripts? Was that an exciting project for you when that began?

MR. HAILE: Very much so for several reasons. Number one, it is salvaging, saving a culture that would be destroyed. Number two, when these manuscripts come together in one place, that is like visiting a museum and studying everything there. You don’t have to climb mountains, go down in the valleys. They are all in one place, so this is a great opportunity for scholars, for the country.

MS. TIPPETT: And I wonder, you know, this word “manuscript.” I did spend some time with Columba Stewart just talking about, you know, what the definition is of a manuscript, because it’s a word that gets used loosely in English. My sense is, and also from some of the stories he told me, that Ethiopia is one of the last cultures where manuscripts in that sense of something that’s been written down are used in ordinary life.

MR. HAILE: Well, we never use the word “manuscript.” We don’t even have a counterpart of it in our language. For us, it is a book. We write a book, we compose a book, we copy a book. As long as it is bound, it is a book. That is what we have daily. The printing came much, much later, and it hasn’t influenced the larger society — especially the ecclesiastical society — yet. So manuscript means book for us and we grew up in it. They are our textbooks, they are our prayer books, they are our daily companion.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me something about the scope and the nature of the work you’ve done these years since you’ve been with the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library in Minnesota. What precisely is the nature of your work?

MR. HAILE: Well, every morning when I come to my office, I open a raffle ticket, you will say, when I open a manuscript or a microfilm. I come with such great curiosity and anticipation. What am I going to see in here? I open the microfilm. I see sometimes a copy of a manuscript, a text that I have cataloged yesterday, so I get frustrated. The next time I open another man’s microfilm, I get something on the marginal, but nothing on the main subject. This I call a consolation information. But then sometimes you find something which even people who microfilm them there didn’t know what it is. And you get excited and you start cataloging in detail and inform the world, those interested in Ethiopian study, in Ethiopian church study, Ethiopian history study. I have to describe the material in detail.

So I always consider myself like a waiter who is hungry and serving tasty foods. The food smells nice. So I say, where am I going to sit down and enjoy myself? How am I going to study this, or shall I only tell the world that there is something and then I don’t get served? I have a problem in living which century I live. When I read those manuscripts, I’m taken away there. Sometimes I’m totally taken with them, with the monks and the ancient libraries and the ancient monasteries and then, when someone passes by me in their office and speaks English, I say, “What?” But then I realize I am in an English-speaking world.

MS. TIPPETT: After a short break, more conversation with Getatchew Haile and with Hill Museum and Manuscript Library Director Father Columba Stewart on how this work is not like a Dan Brown novel, but does contain its share of secret passageways and historic heart-rending discoveries.

The biblical pages in lush colors and lavish script on the walls of the gallery where I Interviewed Columba Stewart are part of the most recent global project to emerge from the monastic community of Saint John’s. The Saint John’s Bible is the first illustrated Bible to be commissioned by a Benedictine monastery since the printing press was invented five centuries ago. It’s being spearheaded by Donald Jackson, the foremost Western calligrapher and Queen Elizabeth’s scribe. You can watch behind-the-scenes video on our website. We’ve also posted a video about the Bible Project on our blog, Pertinent Posts from the On Being Blog. Find links to these features and much more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. On Being comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to On Being, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Preserving Words and Worlds.” We’re at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library in central Minnesota, a quiet, renowned place that rescues and preserves documents from across history and the globe. This library has digitized over 1 million files and holds the world’s largest archive of medieval manuscripts on microfilm.

I’m in conversation with Getatchew Haile, a linguist from Ethiopia who’s been a key figure in the library’s work in that country over the past three decades. In and between extreme political and economic upheaval, Getatchew Haile and co-workers in Ethiopia and Minnesota have worked to photograph prayer books, ancient handwritten copies of the Bible, and other key texts of Ethiopian churches and monasteries. They bring these images back to Minnesota for preservation and further study.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if you could say something about how you would explain to someone, you know, what is threatened and what is lost when these kinds of documents and writings are lost or go missing?

MR. HAILE: Poverty is an enemy of the human being. When someone is in need, that person can probably do anything to survive and this is what is happening with the manuscripts in Ethiopia. The poor people have understood that manuscripts can be sold, and they can get money by selling …

MS. TIPPETT: You mean gift shops and markets, right?

MR. HAILE: Yes, yes. So they go to the monasteries, they go to churches at the wrong time and steal them and sell them. If these books are so lost, they are lost forever. The other day, someone showed me a microfilm copy of a book that was the prayer book of one of the famous emperors who ruled Ethiopia in the 19th century. It was his own Bible. It was his own Psalter, and it is here somewhere in America. Well, at least I wish it was given to a museum. And sometimes when the dealers get these books, you know what some of them do? They cut them into pieces and sell them at retail prices a page. You know, here is a page. Here is another page. This is a great damage. History is lost. The history of Ethiopian Christianity is part of the history of the Christian world, so they have to be integrated and preserved as such.

MS. TIPPETT: And in your mind, is the work you do now in preserving these pieces of history and this knowledge of history, you know, how does this matter for the present and the future of Ethiopia?

MR. HAILE: We have to look at Ethiopia as a country rather than the Ethiopian government. For us, for people who are interested in the interest of their country, an ancient country, and how do we prove that it is ancient? It’s only by showing people the ancient culture, the ancient history, the ancient ruins, the ancient manuscripts. We call them ancient, but at the same time, they are present. We live in them. We live in the sixth century. We live in the seventh century. We live in the 10th century. We live in the 20th century. For us, the time is the same. But if that part is gone, if the ancient part is gone, then we are only people in the 20th century, like countries established by the colonial powers.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. You’re impoverished then.

MR. HAILE: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Which I suppose just speaks to the urgency of the work that HMML is doing and that you’ve been engaged in.

MR. HAILE: Yes. You would be amazed with some of the manuscripts some people in America send me to say, “Can you tell me what this book is?” So I open and look at it. I say, “Well, this is the book we microfilmed in such and such year in Ethiopia, so this means it has disappeared since we microfilmed it.” So several of the manuscripts we have microfilmed, many of them, have disappeared and have shown up here. We can see our traces, because we paginate them before we microfilm them. We will put pages on them so they show up here with the pages we made for them in Ethiopia.

So the urgency is no doubt, and I am so glad that this library was established because the Western world is not — unless some catastrophe comes, I mean, they have preserved their material. But in our case, the only way of preserving the manuscripts is microfilming, because you cannot go and build libraries there. You should see the wear and tear. You should see what the termites do, what the rodents do to the manuscripts, so this is just — it’s a rescue mission, I would say, especially for Ethiopia.

MS. TIPPETT: Ethiopian linguist Getatchew Haile. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being from American Public Media. Today, “Preserving Words and Worlds.” We’re exploring the work and wisdom of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library known as HMML of Saint John’s Abbey and University in Minnesota.

Historian Theresa Vann, heads up the Malta Study Center. This division of the library has been cataloging and preserving archives that include accounts of the Knights of Malta dating back to the 12th century.

MS. VANN: You know, books are the highly portable artifacts. They’re very stable artifacts, and yet they are a great window to the past. This is an example. As you can see, it’s been very well used. It’s been put together with cellophane tape, fabric tape from the 1970s. I remember fixing our dinette set with this. The title, that’s been put on with masking tape. You open the book itself and you see it was printed in 1542, so this is from the 16th century. And the cover, which is coming apart, is actually made out of an even older book. You know, it’s not that they did not value manuscripts. It’s just that, you know, manuscripts got worn out and so the binders collected the scraps and reused them. They were being thrifty.

MS. TIPPETT: Theresa Vann’s descriptions of crude repairs and bookworms tunneling through fleshy parchment come to life on film. Be sure and watch our SoundSeen video of her showing these archival manuscripts at speakingoffaith.org.

I asked HMML Director Columba Stewart — a theologian, historian, and monk of Saint John’s — whether this work with the manuscripts and practices of monastic communities around the world has changed his sense of the relevance of the past to the present and of what it means to be monastic in our time.

FR. STEWART: There have been many experiences I’ve had of living among these ancient communities, which continue to survive. In some cases, they’re flourishing again after almost dying out. There’s something thrilling about being in a monastery in southeast Turkey, Mor Gabriel monastery, and getting up at 4:30 or 5 in the morning and gathering in a church, which has been there since the fourth century with sixth century mosaics, and hearing a group of kids gather around a single large volume of Syriac to chant the liturgy in the same way they’ve done it forever and to know that it’s been sung the same way in the same place for 1,500 or 1,600 years.

And that’s thrilling, and that’s something we don’t have in the West. Even our monastic tradition is not so continuous. So that’s poignant and powerful, and it makes me a little wistful, because it’s not our kind of monasticism. It also makes me think harder about one of the questions that I’m working on now in my own scholarship, which is the nature and the traits of traditional monastic culture and then the really challenging question of how much of that’s possible now. So as a 21st-century Benedictine, how honestly can I say I’m really part of that tradition? So that’s one side of it.

The other side of it is seeing so many monastic traditions which became extinct and sort of picking through the remnants. This is an experience I probably had most powerfully in western Ukraine, where we started a project a year ago, and going to the major state library in Lviv, which is the major city of western Ukraine. This is a place that, at one time, was part of the Austrian Empire. Then it was part of Poland and then it was occupied by the Nazis and then the Soviets had it. So by the Soviet period, of course, they shut down all the churches and the monasteries, took all of the manuscripts, dumped them into a state repository where the curators have done their very best for decades under very difficult circumstances to care for what they have, but can barely digest all of the remnants of religious cultures that have been deposited there.

So I turn up and they take me around the rare book room. Imagine a room not much larger than the gallery that we’re sitting in here, packed to the rafters with manuscripts. They’re pulling things off the shelf and saying, “We don’t really know what this is.’ They hand it to me, and I say, ‘Oh, it’s a 16th-century missal from the Carmelite monastery that used to be here from the Austrian period.’ I look down on a lower shelf and I see 20 Torah scrolls, which are the only remnants of what at one time was one of the most significant Jewish communities in Galicia, which is what that part of Ukraine is called. And the Germans, of course, destroyed all of the synagogues, killed almost all of the Jews, which at one time was 30 percent Jewish until the early ’40s. But somebody salvaged the Torah scrolls, and there they are. They don’t really mean anything to the people there now, because the cultural link has been broken, but somehow miraculously somebody recognized these are important to keep.

So you’re talking to people who are all Ukrainian and modern Ukrainian who have no connection to the Roman Catholic traditions evident in the Latin manuscripts, to the Jewish traditions evident in the Torah scrolls. I’m looking at that and just thinking there are so many layers of extinct culture here — and extinct from the 20th century. So, man, what does that say about the fragility of anything we’re doing?

MS. TIPPETT: What happened to those Torah scrolls? Do you know? Are they still there?

FR. STEWART: They’re still there. There’s an American project which has been trying to track down and inventory them and I know somebody’s looked at them. Most Torah scrolls, you don’t digitize them, A, because they’re holy objects and, B, because it’s copies of the same text and the scribes are so careful. But people are aware of them, and there is, I know, a rabbi in Virginia who’s got a project of trying to find Torah scrolls in private hands in Eastern Europe and basically ransoming them so they can be used as they reestablish congregations in that part of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s kind of an intrigue and mystique that surrounds — I mean, there are more than a fair number of novels, Dan Brown, those kinds of plots to great yarns. I mean, you’ve worked with the Knights of Malta, right?

FR. STEWART: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Which is associated with the Crusades, but also The Maltese Falcon. The Ethiopian monasteries, when Saint John’s went there in the ’70s, I mean, they had documents that people didn’t even know still existed. I wonder if you sometimes had a sense of intrigue and mystery. Is that real when you get close to this stuff?

FR. STEWART: There’s some thrills. I hate the Dan Brown franchise, so I’ll state that here publicly.

MS. TIPPETT: All right.

FR. STEWART: Partly because it’s such bad history and partly because manuscripts don’t work that way. It’s not like there’s some big explosive text we found that has completely …

MS. TIPPETT: That will blow everything wide open.

FR. STEWART: Yeah. It doesn’t work that way. So rather than individual texts having such potency or my sort of waking up in the middle of the night thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it fabulous to find the original copy of X?’ We certainly have been able to photograph some important manuscripts, one of which is going to be published this fall, a unique copy of a Syriac chronicle, which has observations of local Christians on the Crusades. So that’s a fascinating text.

But most of what thrills me is encountering the communities and gaining access to some of these libraries, which are often jealously guarded, because of fear. A lot of these communities, not only centuries of survival under Islam, but also mindful, particularly in places like Turkey, of the Armenian genocide and the much less known genocide of Syrian Christians, which happened in the years immediately after the Armenian genocide. And the fact that libraries were totally lost. Many people were killed. A lot of communities had to leave ancient Christian centers and move across the border to Syria or to Lebanon. Being taken into a place through a secret passageway, a hidden door behind a bookcase and going into a room …

MS. TIPPETT: So there is real intrigue built into it somehow.

FR. STEWART: Yeah. It’s a thrilling experience. And it’s kind of thrilling in the adventure sense, but the real thrill is the poignancy of the moment of trust and the awe of being shown what these people hold most precious and what they really suffered to keep. And that’s extraordinary and that touches me on so many levels. It touches me obviously on a fundamental human level, but on a monastic level, where I have some kind of intuitive sense of what this represents to them. It’s extraordinary.

MS. TIPPETT: This center, this museum and manuscript library, as we discussed early on, its vision and mission have broadened, so you are about cultural preservation — preservation of manuscripts, in particular. You also have original lithographs of Picasso and Chagall and religious subjects, and you have this extraordinary Saint John’s Bible Project. You’re hosting that now. And you’ve written that this is all “a profoundly Benedictine undertaking, that for 1,500 years, Benedictines have been committed to glorifying God by creating, caring for, and preserving books, art, and architecture of enduring quality and beauty.” I just want to tease that out a little better. How does this work, glorify God, in your understanding and your experience of it?

FR. STEWART: Wow, there are so many aspects to that. The biblical quote which inspires that is a line that occurs in Benedict’s chapter on the artisan’s of the monastery. Where having told the artisans of the monastery not to get proud about the particular skills they have and also having told the monastery they should sell their stuff at a slightly lower price than other people do, lest they start to get avaricious about commercial enterprises, Benedict quotes scripture saying, “Whatever else happens, let it be the case that in all things, God is glorified.” So there’s that sense that every aspect of what we do, even the most mundane like things we produce and sell, should glorify God. Benedictines have kind of taken that little hit and run with it. Benedict himself had no idea that Benedictines would build great churches or that we would have scriptoria or that we would be preservers of civilization. He was just trying to start a monastery and have some guidelines for it.

But that notion that everything we do somehow should touch what is most holy and fundamental in our lives and that instinct you find in other parts of the rule — like treat the tools you use in everyday activities like the sacred vessels of the altar — says that everything can be a bearer of the holy. And if, as Benedict says, everyone we meet conveys Christ to us — so the guest, the sick, the pilgrim, our fellow monks whom we meet on a daily basis, as challenging as it can sometimes be to recognize Christ in someone with whom I disagree.

MS. TIPPETT: The people you know too well.

FR. STEWART: Exactly, exactly. That instinct, that sort of sacramental instinct to find something holy in everything, runs deep in us. So I think it’s tended to make us want to do our best whether it’s a humble task or kind of something more exalted like a great work of art. I think on the cultural side, this instinct monks had to keep copying in the Middle Ages, this instinct we’ve had since to study and whether individual monks themselves are involved in these pursuits or not, a basic sense that that’s something important to Benedictines and that that’s a distinctive trait of who we are. And that’s what we’ve continued doing, all of the things that you were just summarizing.

People ask, ‘Well, why do you do this? Why do you run around photographing these manuscripts?’ I say, ‘I don’t particularly have an answer to that right now, apart from that instinct and that spiritual impulse.’ That’s for people over the next several hundred years to say as they read them and use them. But there’s some instinct that we have as Benedictines that all of these things should be cherished and particularly things that are threatened in places where they may be lost or destroyed. They should be cherished and they should be cherished somewhere in particular.

MS. TIPPETT: As you’ve said, manuscripts that are so endowed with peoples’ sense of what is holy, that are cherished in those communities.

FR. STEWART: And they should be safe somewhere and this is that place.

MS. TIPPETT: Father Columba Stewart is a monk of Saint John’s Abbey and executive director of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library in Collegeville, Minnesota. This is a 1963 recording of the monks of Saint John’s Abbey performing a polyphonic motet, “Jesu Dulcis Memoria.”

[Sound bite of “Jesu Dulcis Memoria”]

MS. TIPPETT: In the creative ferment of the 1960s, Saint John’s Abbey and University helped found our parent company and has supported it across the years. Several decades later, these Benedictines played an important role in my imagination about creating this public radio program. I’ve written about this on our blog, Pertinent Posts from the On Being Blog. And we take you to the places we visit so you can see some of the rich visuals that bring manuscript preservation to life. Download MP3s of this program and my unedited interviews with Columba Stewart and Getatchew Haile on our Web site, speakingoffaith.org.

On Being is produced by Colleen Scheck, Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, and Shubha Bala. Our producer and editor of all things online is Trent Gilliss. A special thanks for this program to Matthew Heintzelman, Linda Orzechowski, Tim Ternes, Wayne Torborg, and Theresa Vann. Kate Moos is the managing producer of On Being. And I’m Krista Tippett.