Conor Kerr

Winter Songs

Conor Kerr’s “Winter Songs” depicts a future scene: coyotes roaming through a rewilded city, digging up the bones of Indigenous ancestors who then regenerate and reclaim what was taken. Power is dismantled, something original is restored.

We’re pleased to offer Conor Kerr’s poem, and invite you to read Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen back to all our episodes.

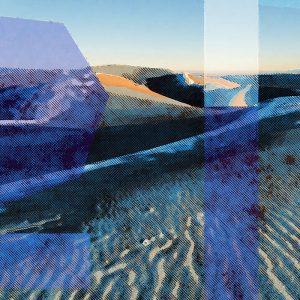

Image by Annisa Hale/ Film processed by Moody's Film Lab, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Conor Kerr is a Métis/Ukrainian writer living in Edmonton. A member of the Métis Nation of Alberta, he is descended from the Lac Ste. Anne Métis and the Papaschase Cree Nation. His Ukrainian family are settlers in Treaty 4 and 6 territories in Saskatchewan. He is the author of the poetry collections An Explosion of Feathers and Old Gods, as well as the novel Avenue of Champions, which was shortlisted for the Amazon Canada First Novel Award, longlisted for the 2022 Giller Prize, and won the 2022 ReLIT award. Conor is an assistant professor at the University of Alberta where he teaches creative writing. Image by Hot Neon Productions.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I love being in a place where you can look out at the cliff or the hills or the landscape and think, “This hasn’t changed too much in the last 50 years, a hundred years, 500 years.” But of course, then, so often in the town or village or city, there’s enormous change, such that it’s almost impossible to imagine what the land looked like before. But of late even there, I begin to think, “What did this place look like and what is the memory of that land here? And what does it mean to be informed by that land, which has stood and been changed as a result of human occupation and wars and industry? What does it mean nonetheless, to recognize the land in which I stand?”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Winter Songs” by Conor Kerr

“Two coyotes. Full winter coats puffed out. Follow their morning run

through the back alleys and train tracks under generations of graffiti

and abandoned murals of 80s sports stars. The discarded shells of

burned-out and abandoned land-value-only buildings stand watch over

their paw prints left in snow not yet spoiled. Somewhere above, mag-

pies announce their arrival into the territory. Angels welcoming gods

of a city gone back to the land through trumpet fare, and the remnants

of an “O Canada” anthem playing on endless repeat from abandoned

stadiums.

“Two coyotes walk back 150 years to a time before skyscrapers and

suburbs—man-made lakes, dams, bridges and power plants—and

dig up the bones of ancestors laid along the riverbanks. Watch them

rise up to dismantle the structures placed on top of quarter sections

that divided a country. They spool back barbed wire and let the bison

pound the houses into kindling for their winter fires. Marble legisla-

ture pillars crushed under the weight of an elk skull. A coyote’s god

lives in bones.”

[music: “Arrival at Kirkenes” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Conor Kerr is a poet as well as an award-winning novelist. And this poem is so cinematic, you can see what’s happening and so much of time and space and setting and change and the restoration of things is mentioned in these few hundred words. The opening of the poem locates us in winter and it locates us, particularly, in the morning, the back alleys and train tracks and there’s graffiti, “generations of graffiti” and “murals of 80s sports stars.” It’s a city or part of a city that’s abandoned and burnt out.

And even then into the second section of the poem, “man-made lakes, dams, bridges and power plants.” You see industry everywhere and you begin — because of the way that the poem speaks — to see everything through the characters, through the eyes of these coyotes or coyotes — and I’m just going to go back and forth in terms of pronouncing it in the different ways — these coyotes are time travelers. They are present in this winter and in the abandoned parts of a city, but they also are able to bring us back to a time before. They see ancestors and they “dig up the bones” of those ancestors. In that way, they are functioning, in a certain sense, as the carriers of memory and the adaptable carriers of memory because they knew how to survive and thrive and find sustenance and food and rear litters 150 years ago, as well as in the abandoned parts of a city.

Then the ones that they dig up begin to dismantle dividing structures, what you see is that the poem, the ancestors, the coyotes, the poet are putting, by association, the things that divide a country and barbed wire and legislature pillars into the categories of things which separate that which shouldn’t be separated. The ancestors dug up and the coyotes, too, as well as the bison and the elk, are tenders of the land. The coyotes aren’t enemies or wild dogs with derogatory reputations. They know and they’re repositories in this poem.

[music: “Slate Tracker” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The book from which this poem comes is called Old Gods. And Conor Kerr describes the book kind of jokingly as a Métis guy driving around the prairies. He is Métis and Ukrainian, and he’s looking at the experience of isolation and dislocation that can come from very particularly imported ideas about home and place. When he’s saying that home and place aren’t necessarily just a single solitary building or an apartment, but a location within land. He’s a member of the Metis Nation of Alberta and a descendant of Lac Ste. Anne Métis and Papaschase Cree nation and his Ukrainian family are settlers in Treaty Four and Six territories in Saskatchewan.

This poem is titled “Winter Songs,” and at the end of the first stanza of this prose poem, there’s a reference to the Canadian national anthem, “O Canada” “playing on endless repeat from abandoned / stadiums.” There’s a controversy about the singing of the Canadian national anthem and how it goes on shortly after saying, “O Canada” to speak about native land. Whose native land? And who can call it native land? And what does it mean to make that easy for people to sing without, perhaps, their responsibility to pay attention to what it would mean if you called it native land on Native land, the recognition of treaties, treaties that have been betrayed?

This is present throughout the book of Conor Kerr’s and you see it present in this poem, too. The juxtaposition of “Winter Songs” perhaps coming in the way of recognizing all that is living and all that is protesting and all that is needing to be remembered through the songs that are being evoked in this poem. And the contrasting of that with national anthem. And he characterizes this in the poem by saying that the “anthem playing on endless repeat from abandoned / stadiums.” “Endless” and “abandoned” really stand out to me in this line as demonstrating his own critique of what it is that those songs gather and what it is that the “Winter Songs” could gather.

[music: “Snowcrop” by Blue Dot Sessions]

You can learn a lot going into this poem — especially the last part of it — through one particular verb. It’s after the bones of the ancestors have been dug up, and then it says, “Watch them / rise up to dismantle the structures placed on top of quarter sections / that divided a country.” But “dismantle the structures.” The verb “dismantle” comes from the noun mantle, which in some uses of it, is the placing of a ceremonial cloak to confer authority to someone. And so to dis-mantle structures that are placed “on top of quarter sections” — this is not necessarily about destroying, it is about placing authority where it should be placed because the structures that are being critiqued in the poem have divided. And the impetus of this poem seems to be to reunite: to reunite people to their place in the world, which is place in relationship with the cultures and traditions and languages of that land.

[music: “Taoudella” by Blue Dot Sessions]

We know the span of time in this poem that there is a moment when these coyotes come into a particular city, and then they go back 150 years. And so while we know the span of the poem, we don’t know the when of the poem. Is this from 2024 back 150 years before? Is this from 2154 back 150 years? What’s being imagined? Is this a future scenario where certain places have been left behind and what is being restored? Is the presence of animals there who have been present in many places and times before?

One of the things that traversing of time does is to say what is the past for some is not the past for all. And what for some people would say, “Oh, that’s ancient history.” Somebody can say that about something that happened last year, never mind 150 years ago. The poem is asserting that what some people would call ancient history — 150 years — is not ancient history at all. It is remembered and time that is remembered has a different quality than time that is only thought about through the lens of history or architecture. And the ancestors become re-membered through their bones being dug up and the structures that do work for a community of people, those things are re-membered having been dis-membered through the project of Europeanization of a country. What Conor Kerr is proposing, I think, is that no matter what happens in the future that there will be the capacity for the land to return to what it has known that it needs for survival all along. And this poem is creating that landscape in an imagined but also an assertive way.

[music: “Ultima Thule” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Winter Songs” by Conor Kerr

“Two coyotes. Full winter coats puffed out. Follow their morning run

through the back alleys and train tracks under generations of graffiti

and abandoned murals of 80s sports stars. The discarded shells of

burned-out and abandoned land-value-only buildings stand watch over

their paw prints left in snow not yet spoiled. Somewhere above, mag-

pies announce their arrival into the territory. Angels welcoming gods

of a city gone back to the land through trumpet fare, and the remnants

of an “O Canada” anthem playing on endless repeat from abandoned

stadiums.

“Two coyotes walk back 150 years to a time before skyscrapers and

suburbs—man-made lakes, dams, bridges and power plants—and

dig up the bones of ancestors laid along the riverbanks. Watch them

rise up to dismantle the structures placed on top of quarter sections

that divided a country. They spool back barbed wire and let the bison

pound the houses into kindling for their winter fires. Marble legisla-

ture pillars crushed under the weight of an elk skull. A coyote’s god

lives in bones.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Winter Songs” comes from Conor Kerr’s book Old Gods. Thank you to Nightwood Editions who gave us permission to use Conor’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Amy Chatelaine, Kayla Edwards, Annisa Hale, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s book, Poetry Unbound: Fifty Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.